INTRODUCTION

It is the social accountability of teaching hospitals and the academic society to educate residents and produce qualified specialists. Residency training is an important and essential way of protecting community health and responding to social health needs. Discussions on residency training in Korea have predominantly been on the supply and demand of residents,

12 training period,

34 and the lists of required diseases and procedures. Because of the traditional apprenticeship of graduate medical education (GME) and lack of advanced curricular development, the quality of training has relied on the competence of individual trainers and institutions. Human resources are recognized as important in hospitals, and yet residents often work in poor work conditions and their right to education is not adequately protected in closed training environments.

5 As a reaction to claims and resistance from trainees, the Act for the Improvement of the Training Environment and Status of Residents

6 was enacted in 2020. Trainees’ working hours was limited through this act, and it was accepted that residents’ rest was directly related to patient safety.

A training period must be determined to secure the appropriate outcome of the training program. This period should also be determined according to an outcome-based curriculum, defining the competencies to be achieved gradually. However, there have been no studies in Korea for adjusting the training period and contents to the assessed needs.

Competency-based medical education (CBME) is the most important principle of current medical education and is the global standard. In 1981, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), an independent institution for the certification of GME programs was established in the United States.

7 ACGME recommends planning and implementing the training program based on core competencies and evaluates the program of each institution. In Canada, the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and College of Family Physicians of Canada define the physician competency framework as CanMEDS, with seven core competencies.

8 In Korea, the foundation for CBME was laid when the Future Roles of Korean Doctors (i.e., 1. practice, 2. communication and cooperation, 3. social responsibility, 4. professionalism, and 5. education and research) was established and published in 2014.

9 The patient-centered doctor’s competency framework in Korea for physicians was defined and announced by Jeon et al. in detail, in another sub-study of this research.

10

The establishment of the Korean Institutes of Medical Education and Evaluation in 2003 prepared the accreditation for basic medical education (BME), gradually raising the standards of certification to meet global standards.

11 Medical schools have made efforts to improve quality in line with accreditation standards. The improvement of GME is still nascent compared to BME. The research to design and implement the residency training curriculum began with the leadership of the Ministry of Health and Welfare and Korean Hospital Association, in response to the demands by residents for improving GME curriculum, during the doctors’ strike in 2020. The Ministry of Health and Welfare provides funding to each academic society to improve residency education and training programs based on CBME, but the projects are limited to competencies for specialties, without any common core competencies. However, society is demanding patient-centered healthcare, which requires not only expert competencies for specialties, but also common core competencies.

The GME program in Korea is certified by providing the hospital’s individual training program, following the established minimal requirements (the number of patients per year, diseases that must be experienced, procedures considered essential, conference attendance, publications, etc.). However, systems such as a definition of competencies, curricula based on competencies, teaching and learning methods, and assessment plans, are lacking. In Korea, each academic society is entrusted with the qualification of the specialist board, the certificate of which is provided by the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

The Korean Association of Internal Medicine published a core competency guidebook for internal medicine (IM) residency training in 2017, and listed symptoms and signs, diseases, and procedures that must be covered during the training period.

12 This guidebook defined key elements among patient care competencies as an IM specialist. Patient-centered outcomes can be achieved when common core and specialist competencies are achieved in a balanced manner. This study was conducted to assess needs that fill the gap between the defined competencies and learners’ achievements, in order to develop a revised IM training curriculum. We investigated the needs of both competencies for a specialist from the core competency guidebook for IM specialty, and common core competencies suggested by the Korean Academy of Medical Science.

13 We would like to suggest the urgent competencies or items to develop a training curriculum, and revise the educational strategies for learning and assessment.

METHODS

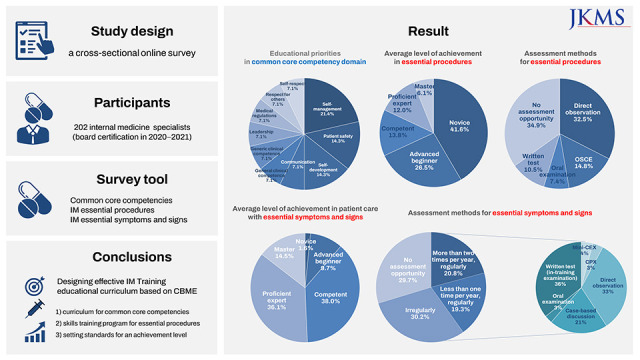

Study design

This study implemented a cross-sectional online survey, via a web link (

http://b19.hrcglobal.com/?PN=py254), which was conducted by Hankook Research Company in September 2021.

Participants

The participants were 1,200 IM specialists (who obtained board certification in 2020−2021) within 2 years of completing their 3-year IM residency training, after the period of IM training was changed from the 4-year system to the 3-year system. The purpose of the study was explained to the community of IM specialists and their cooperation was requested, so that the research explanation and consent form could be sent, and only those who agreed could respond to the questionnaire via an online link. In total, 202 participants responded to the questionnaire. The calculated sample size for this study was 172 at a 90% confidence level, 5% margin of error, and an effect size of 0.5 by G*Power 3.1.9.7. Response data exceeding the number of samples required for statistical analysis were collected. The demographic characteristics of survey respondents are shown in

Table 1.

Table 1

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents

|

Characteristics |

No. (%) |

|

Time of IM specialist qualification |

|

|

Within 1 year |

91 (45.0) |

|

Within 2 years |

111 (55.0) |

|

Gender |

|

|

Male |

117 (57.9) |

|

Female |

82 (40.6) |

|

Non-responder |

3 (1.5) |

|

Location of training hospital |

|

|

Capital area |

134 (66.3) |

|

Non-capital area |

68 (33.7) |

Survey tools

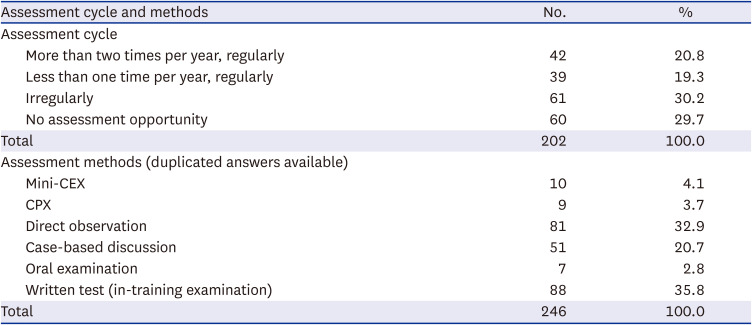

We developed a questionnaire to investigate the self-evaluation of common core competencies and the achievement level for IM essential competencies, level of importance of each competency, teaching and learning methods, and assessment methods at the time of completion of the 3-year IM residency training.

We developed the common core competencies as a questionnaire for each competency of 14 detailed categories in eight domains. This was referenced in Chapter 2 of the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s Notification No. 2019-34, Annual Training Curriculum for IM residents, as necessary competencies during the training course.

The importance of each competency was measured on a 5-point Likert scale from “very important” to “not important at all” (Cronbach’s α = 0.974), and the achievement level was scaled on five levels (novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient expert, and master; Cronbach’s α = 0.984). Each achievement level was also used as a self-evaluation scale for the IM essential competency (“procedures” and “symptoms and signs”). It was modified and presented to suit the content of the patient care situation, for the procedures, symptoms, and signs. The specific contents corresponding to each achievement level are as follows:

1. Novice: I know the content, but it is difficult to practice.

2. Advanced beginner: I can practice this content, but depending on the situation, I need the advice of an instructor.

3. Competent: I can practice on my own in most situations.

4. Proficient expert: I can practice proficiently in most situations.

5. Master: I can demonstrate my expertise proficiently in any situation.

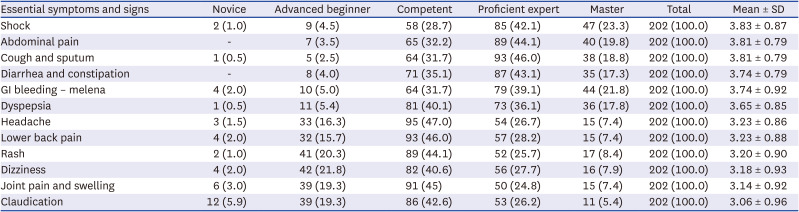

The questionnaire on IM essential competencies was developed as competencies (five procedures, 31 symptoms and signs) that required evaluation by a supervisor, among the essential competencies for resident training in the Korean Society of Internal Medicine.

12 Respondents were asked to check their achievement levels regarding the five procedures required for assessment by their supervisor (Cronbach’s α = 0.790), and select an assessment method. In addition, their achievement levels for 31 symptoms and signs that require assessment by a supervisor were checked (Cronbach’s α = 0.984), and they were asked whether they were assessed regularly, and how they were assessed.

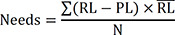

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, we initially calculated the frequency and percentage of examining participants’ general characteristics. Second, paired t-test, the Borich Needs Assessment formula, and the Locus for Focus Model were used to prioritize the educational needs for the common core and essential competencies of IM specialists. The Borich Needs Assessment formula is as follows:

RL: required level, PL: present level, RL̄: average of the required level, N: total number of cases

Third, χ2 analysis was performed to examine the relationship between participants’ gender; location of the training hospital; and participants’ achievement levels in essential procedures, symptoms, and signs. We used IBM SPSS ver. 23 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for the analyses; significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethics statement

The current study’s protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungnam National University College of Medicine (approval No. CNUH 2021-02-025). Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the time of the survey.

DISCUSSION

The most important condition preceding the development of the competency-based curriculum is that its framework should be well defined.

1415 Competencies in competency-based graduate medical education should serve as a goal at the time of completion of residency training, and should be divided into sub-competencies or milestones to construct outcomes that must be progressively achieved according to the training year. Since the trainee’s development process is conducted through step-by-step development, it is necessary to set detailed training objectives to be achieved at each stage, which are known as milestones. The milestones and exit outcomes must be agreed upon in advance with stakeholders. After the Ministry of Health and Welfare provided funding to each academic society, they also actively worked to identify entrustable professional activities (EPAs).

16 Since EPAs are physicians’ activities comprising several competencies, it is difficult to formulate the EPA without a solid competency framework as well as the EPA-based curriculum development, including teaching, learning, and assessment methods. Moreover, residents are not only trainees becoming specialists, but also licensed doctors who have legal and administrative responsibilities in medical practices. An agreement on GME competencies and milestones or EPAs can be used as guidelines that suggest the limitation of legal and administrative responsibilities in the clinical practices of trainees.

Competencies consist of common competencies for all doctors, including specialists, and specialist-specific competencies, according to the individual doctor’s specialization. Common competencies include many that make most patients feel valued, such as patient safety, clinical ethics, and communication. The Research Institute for Healthcare Policy released a report detailing the development of a generic curriculum for GME, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of licensed doctors,

17 which is based on original research about RESPECT 100 of The Korean Institutes of Medical Education and Evaluation.

18 The Korean Medical Association received research funds from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, and conducted a study on the reformation of the training curricula for each specialty, for the efficient training and education of trainees. This study was proposed based on the RESPECT 100 study in Korea,

13 six core competencies of ACGME in the U.S.,

19 seven core competencies of CanMEDS in Canada,

8 and four common competencies of Good Medical Practice in the U.K.

20 In February 2019, the Ministry of Health and Welfare announced the training curriculum of residents by year, and the urgent need to develop and implement a common competency education.

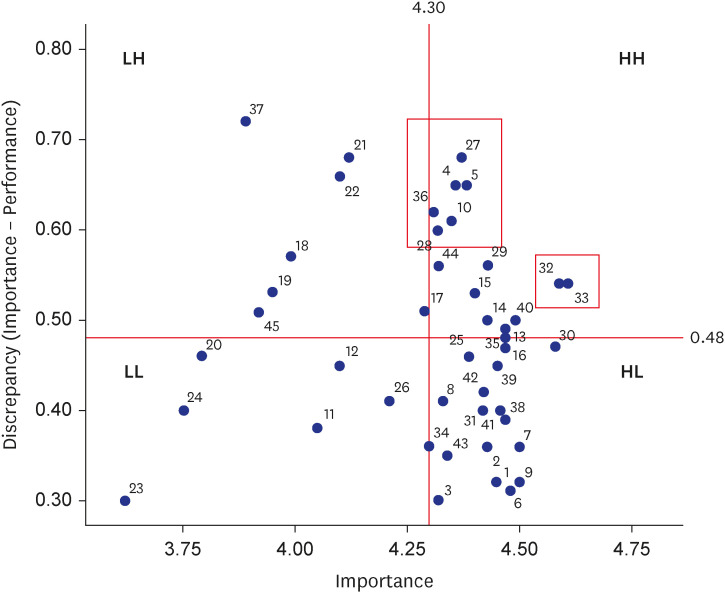

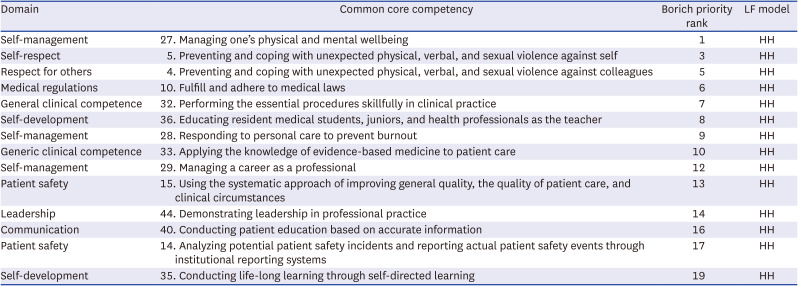

Within 2 years of completing the training, IM specialists recognized that their achievement level was lower than recommended for all the common core competencies (

Supplementary Table 1). Overall, self-management-related competencies were heavily linked to educational priorities (

Fig. 1,

Table 2). Notably, education on common core competencies was insufficient, and even if education was provided, trainees complained that they experienced difficulties in attending the sessions. In the survey on disability factors affecting participation in education opportunities and its impact on common core competencies, the most common response was that there was not enough time to participate in educational sessions due to busy clinical situations (Likert scale = 4.07). Next, the educational time provided did not match the time available for learning (3.88). The difficulty of securing a replacement for a trainee’s clinical work (3.57) also showed high scores. Lack of education-related information (3.57) and support systems such as academic expenses also scored higher than average (data not shown). This means that active promotion and support for common core competency education are necessary. In response to the question about which agent should play a central role in common core competency education, training hospitals (44.4%) and government agencies such as the Ministry of Health and Welfare (30.6%) received the highest scores (data not shown).

21 Depending on the common core competencies, we suggest that education on domains such as “respect for self,” “respect for others,” “self-management,” and “patient safety” can be effective at the training hospital level, and education on domains such as “medical regulations” and “understanding the social and health care system” can be effective at the level of the government or hospital association.

In addition, physical and mental wellbeing and coping with physical, verbal, and sexual violence ranked high. This proves that further improvement in the residency training environment is still needed, although the Act for the Improvement of the Training Environment and Status of Residents is currently being implemented. It is well-known that preceptors, hospital administrators, and trainees must recognize the importance of common core competencies and reflect them in training and education. In addition, more support is required to improve the training environment.

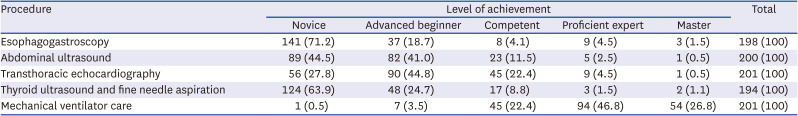

A systematic process for curriculum development must be adapted for a more structured GME curriculum. IM competencies are divided into patient care with essential symptoms and signs and essential procedures of IM specialists. The result was much higher for mechanical ventilator care than the other skills regarding esophagogastroscopy, abdominal ultrasonography, and transthoracic echocardiography (

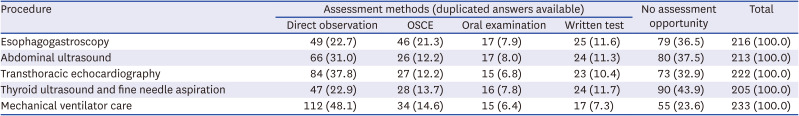

Table 3). These results suggested that most IM training education is biased toward inpatient training and is not conducted evenly for each essential procedure. It is necessary to redetermine the score of essential procedures, or reset the level of achievement downward at the time of IM training completion, after reevaluating whether the essential procedures have been accurately selected. If essential procedures for IM specialists are decided, these must be incorporated in education and evaluated beyond the competent level. There are few cases of direct observation and OSCE (

Table 4), which are appropriate evaluation methods for clinical skills. This result indicated that assessment methods regarding the training of essential procedures must be structured through systematic curriculum development. There are also a few cases where regular assessment is conducted (data not shown). The number and timings of assessments must be determined for each essential procedure, along with the development of the curriculum.

Similar results were observed in procedures for self-directed learning (SDL). While procedures such as thoracentesis, central venous catheterization, or bone marrow examination, which trainees had to perform by themselves in inpatient care, were rated as “competent” by more than 80% of respondents, procedures such as colonoscopy and bronchoscopy, which sub-specialists perform, were rated as “novice” or “advanced beginner” by more than 80% of them (

Supplementary Table 3). The target level of achievement for the SDL procedures were not determined at the time of completion of IM training. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the level of achievement for each procedure of SDL, and to consider the competence continuum from junior trainees to sub-specialists. Thus, the curriculum must provide learning materials and opportunities for SDL procedures.

To make learning opportunities safe, a skills education center could be built by an academic society. A relevant example, led by an academic society, is the skills education center of the Korean Surgical Society. If all the necessary education regarding procedures is not available at each training hospital, it will be useful to separate the education available to individual hospitals and procedures that can use the skills education center. In a skills education center, common core competencies such as “respect for others,” “clinical ethics,” and “communication” and specialist-specific competency such as decision-making abilities in a specific field, can be simultaneously evaluated using standardized patients.

The item with the highest level of achievement in patient care with essential symptoms and signs is shock, which reflects the training situation where IM trainees play a vital role in urgent situations of inpatient care. Following “shock,” patient care with symptoms and signs of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and pulmonary systems all show high levels of achievement, which are related to the required number of patients (gastrointestinal system: 160 patients, cardiovascular system: 140 patients, pulmonary system: 120 patients) to qualify for a board examination.

22 Items showing low achievement levels were mainly those that overlapped with other specialties. It seems that there is a correlation between learning opportunities in the workplace (work-based learning), and achievement levels in patient care with essential symptoms and signs.

It is essential to decide on assessment methods, develop appropriate tools, and train assessors for implementing competency-based GME. The Korean Association of Internal Medicine is working to develop an e-portfolio with assessment tools and a learning activity log, and to train preceptors to evaluate the competencies of their residents. Faculty development plans such as feedback, assessment, and trainee support should be included in curriculum development. Thereafter, remediation programs should be prepared for trainees with competencies at underachievement levels. Preceptors should monitor residents’ progression and encourage them to meet the standards of the competency level. The most advanced residency program provides a flexible training period with the trainee’s individual ability or situation because the designated time to reach all defined competencies is at the point of completion of the training.

81923 Moreover, the quality of training programs and trust from the community can be ensured by accreditation bodies such as ACGME, when certifying training hospitals or related academic societies.

Needs assessment is the first step to curriculum development. We conducted a needs assessment with the core competency guidebook for IM specialty and common core competencies, suggested by the Korean Academy of Medical Science, for developing a competency-based training program. Five aspects that need assessments to develop and revise the IM training education program are identified by this study: 1) developing a curriculum for common core competencies, 2) structuring a skills training program for essential procedures, 3) setting standards for an achievement level in patient care with essential symptoms and signs, 4) designing effective assessment methods and developing assessment tools, and 5) training preceptors as teachers, assessors, and supporters through faculty development. This study was conducted with IM specialists within 2 years of completion of training, but we think it will not differ considerably from the situation of other specialties. Therefore, our results could provide insights to support the development of training curricula across academic societies and training hospitals.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download