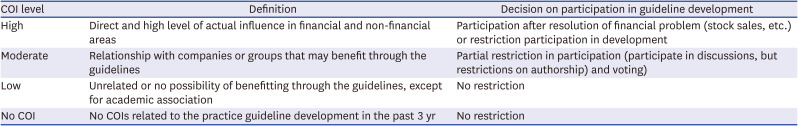

|

Recommendations for medication treatments |

|

|

|

|

|

Remdesivir |

Revision Jan 2023 |

1. For patients with severe COVID-19 who require oxygen therapy but do not require mechanical ventilation or ECMO, we suggest using remdesivir. |

Low |

B |

|

2. For patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 who are at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19, we suggest using remdesivir. |

Low |

B |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

We recommend use within 7 days of symptom onset. When administering to patients with mild or moderate COVID-19, we recommend administration for 3 days. However, if the patient’s condition progresses to severe COVID-19, the duration of remdesivir may be extended as recommended in severe COVID-19. |

|

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) inhibitor |

Revision Jan 2023 |

1. For patients with COVID-19 who require high-flow oxygen or invasive/non-invasive mechanical ventilation, we recommend using tocilizumab. |

Moderate |

A |

|

2. For patients with mild COVID-19, we suggest against the use of tocilizumab. |

Moderate |

C |

|

3. We are unable to make a recommendation for or against the use of sarilumab for patients with COVID-19, in consideration of the situation in South Korea. |

Low |

I |

|

Selective JAK inhibitor |

Revision Dec 2022 |

1. For patients with severe COVID-19 who require oxygen therapy but do not require mechanical ventilation, we suggest using baricitinib. |

Moderate |

B |

|

2. For patients with severe COVID-19 who require oxygen therapy but do not require mechanical ventilation, we suggest using tofacitinib. |

Low |

B |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

We suggest co-administration of standard treatments, such as antiviral agents and steroids, with baricitinib or tofacitinib as long as there are no contraindications. |

|

3. We are unable to make a recommendation for or against ruxolitinib for patients with COVID-19 due to insufficient evidence on its efficacy and safety. |

Very low |

I |

|

Monoclonal antibody therapy |

Revision Dec 2022 |

1. For patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 at high risk for progression to severe disease who cannot use other antiviral agents, we suggest monoclonal antibody, in which case bebtelovimab. |

Low |

B |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

1) Conditions associated with high risk for progression to severe COVID-19. |

|

2) Monoclonal antibody acts by specific binding to SARS-CoV-2. Thus, the choice of monoclonal antibody product should be guided by the current information on the SARS-CoV-2 variants circulating in Korea. |

|

2. For patients with severe or critical COVID-19, we recommend against using monoclonal antibody except for clinical trials. |

Expert consensus |

|

3. When omicron and its subvariants are major variants circulating in Korea, we do not recommend monoclonal antibodies other than bebtelovimab, such as amubarvimab/romlusevimab, bamlanivimab, bamlanivimab/etesevimab, casirivimab/imdevimab, etesevimab, regdanvimab, and sotrovimab. |

Expert consensus |

|

4. For patients who are not expected to mount adequate immune response after vaccination or those who could not complete vaccination due to severe adverse reactions to the COVID-19 vaccine, we suggest using tixagevimab/cilgavimab for pre-exposure prophylaxis. |

Expert consensus |

|

Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (paxlovid) |

New Nov 2022 |

For patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 who are at least 12 years old, weigh more than 40 kg, and have risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19, we suggest using nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (paxlovid). |

Low |

B |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

We recommend the use of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (paxlovid) within 5 days from symptom onset. |

|

Molnupiravir |

New Jan 2023 |

For patients 18 years or older with mild or moderate COVID-19 at high risk for progression to severe disease who cannot use other treatment options,a we suggest using molnupiravir. |

Low |

B |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

We recommend use of molnupiravir within 5 days from symptom onset. |

|

Steroids |

Revision Nov 2022 |

1. For patients with severe or critical COVID-19, we recommend using steroids. |

Moderate |

A |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

The recommended dose of steroids is 6 mg of dexamethasone per day for up to 10 days (if discharged earlier than 10 days, then up to the day of discharge). Other steroids with similar potency may be administered as an alternative (160 mg of hydrocortisone, 40 mg of prednisone, or 32 mg of methylprednisolone). |

|

2. For patients with mild to moderate COVID-19, we recommend against the use of steroids. |

Moderate |

D |

|

Inhaled steroids |

Revision Nov 2022 |

For patients in early stage of COVID-19, we are unable to make a recommendation for or against inhaled steroids due to insufficient evidence on its efficacy and safety. |

Low |

I |

|

Interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitor |

Revision Nov 2022 |

We suggest against the use of anakinra (IL-1 inhibitor) for patients with COVID-19 except for clinical trials. |

Moderate |

C |

|

Specific intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) |

Revision Nov 2022 |

We are unable to make a recommendation for or against the use of SARS-CoV-2 specific IVIG due to insufficient evidence on its efficacy and safety. |

Low |

I |

|

Convalescent plasma therapy |

Revision Mar 2023 |

1. For patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19, we suggest against the use of convalescent plasma. |

Low |

C |

|

2. For patients with mild COVID-19, we are unable to make a recommendation for or against the use of convalescent plasma due to insufficient evidence on its efficacy and safety. |

Low |

I |

|

Non-specific intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) |

Retain Dec 2021 |

We suggest against the use of anti-SARS-CoV-2-non-specific IVIG for patients with COVID-19, except when indicated for treatment of complications. |

Low |

C |

|

Protease inhibitors |

Retain Dec 2021 |

1. We are unable to make a recommendation for or against the use of camostat for patients with COVID-19 due to insufficient evidence on its efficacy and safety. |

Low |

I |

|

2. We are unable to make a recommendation for or against the use of nafamostat for patients with COVID-19 due to insufficient evidence on its efficacy and safety. |

Very low |

I |

|

Ivermectin |

Retain Dec 2021 |

1. We are unable to make a recommendation for or against the use of ivermectin for patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 due to insufficient evidence on its efficacy and safety. |

Low |

I |

|

2. We are unable to make a recommendation for or against the use of ivermectin for patients with severe COVID-19 due to insufficient evidence on its efficacy and safety. |

Very low |

I |

|

Interferon |

Retain Dec 2021 |

We recommend against the use of interferon for patients with COVID-19. |

Low |

D |

|

Other antiviral agents |

Retain Dec 2021 |

1. We suggest against the use of favipiravir for patients with COVID-19 except for clinical trial. |

Very low |

C |

|

2. We suggest against the use of umifenovir for patients with COVID-19 except for clinical trial. |

Very low |

C |

|

3. We are unable to make a recommendation for or against the use of baloxavir marboxil for patients with COVID-19 due to insufficient evidence on its efficacy and safety. |

Very low |

I |

|

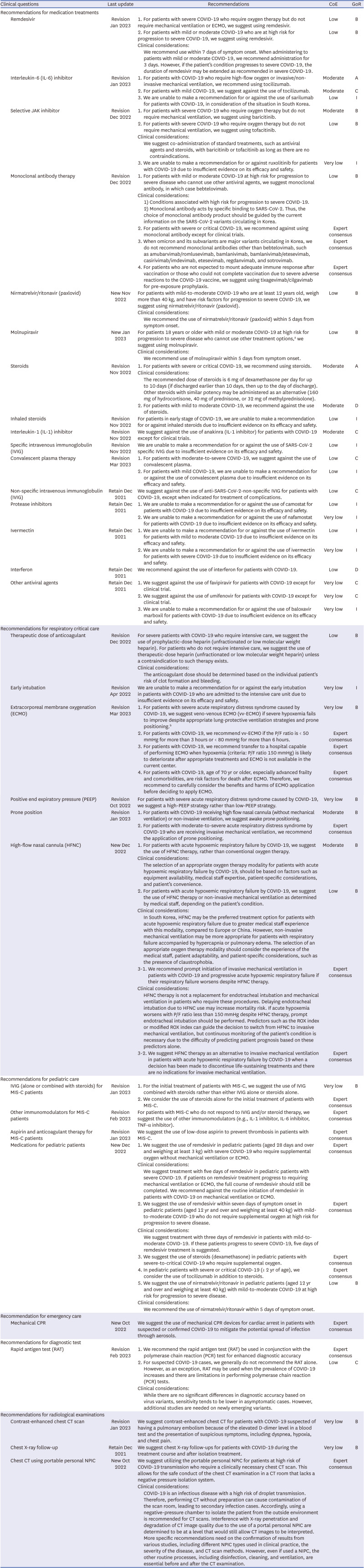

Recommendations for respiratory critical care |

|

|

|

|

|

Therapeutic dose of anticoagulant |

Revision Dec 2022 |

For severe patients with COVID-19 who require intensive care, we suggest the use of prophylactic-dose heparin (unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin). For patients who do not require intensive care, we suggest the use of therapeutic-dose heparin (unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin) unless a contraindication to such therapy exists. |

Low |

B |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

The anticoagulant dose should be determined based on the individual patient's risk of clot formation and bleeding. |

|

Early intubation |

Revision Apr 2022 |

We are unable to make a recommendation for or against the early intubation in patients with COVID-19 who are admitted to the intensive care unit due to insufficient evidence on its efficacy and safety. |

Very low |

I |

|

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) |

Revision Mar 2023 |

1. For patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by COVID-19, we suggest veno-venous ECMO (vv-ECMO) if severe hypoxemia fails to improve despite appropriate lung-protective ventilation strategies and prone positioning.b

|

Very low |

B |

|

2. For patients with COVID-19, we recommend vv-ECMO if the P/F ratio is < 50 mmHg for more than 3 hours or < 80 mmHg for more than 6 hours. |

Expert consensus |

|

3. For patients with COVID-19, we recommend transfer to a hospital capable of performing ECMO when hypoxemia (criteria: P/F ratio 150 mmHg) is likely to deteriorate after appropriate treatments and ECMO is not available in the current center. |

Expert consensus |

|

4. For patients with COVID-19, age of 70 yr or older, especially advanced frailty and comorbidities, are risk factors for death after ECMO. Therefore, we recommend to carefully consider the benefits and harms of ECMO application before deciding to apply ECMO. |

Expert consensus |

|

Positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) |

Revision Oct 2022 |

For patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by COVID-19, we suggest a high-PEEP strategy rather than low-PEEP strategy. |

Very low |

B |

|

Prone position |

Revision Jan 2023 |

1. For patients with COVID-19 receiving high flow nasal cannula (without mechanical ventilation) or non-invasive ventilation, we suggest awake prone positioning. |

Moderate |

B |

|

2. For patients with moderate-to-severe acute respiratory distress syndrome by COVID-19 who are receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, we recommend the application of prone positioning. |

Expert consensus |

|

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) |

New Dec 2022 |

1. For patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure by COVID-19, we suggest the use of HFNC therapy, rather than conventional oxygen therapy. |

Moderate |

B |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

The selection of an appropriate oxygen therapy modality for patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure by COVID-19, should be based on factors such as equipment availability, medical staff expertise, patient-specific considerations, and patient’s convenience. |

|

2. For patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure by COVID-19, we suggest the use of HFNC therapy or non-invasive mechanical ventilation as determined by medical staff, depending on the patient’s condition. |

Low |

B |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

In South Korea, HFNC may be the preferred treatment option for patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure due to greater medical staff experience with this modality, compared to Europe or China. However, non-invasive mechanical ventilation may be more appropriate for patients with respiratory failure accompanied by hypercapnia or pulmonary edema. The selection of an appropriate oxygen therapy modality should consider the experience of the medical staff, patient adaptability, and patient-specific considerations, such as the presence of claustrophobia. |

|

3-1. We recommend prompt initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with COVID-19 and progressive acute hypoxemic respiratory failure if their respiratory failure worsens despite HFNC therapy. |

Expert consensus |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

HFNC therapy is not a replacement for endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation in patients who require these procedures. Delaying endotracheal intubation due to HFNC use may increase mortality risk. If acute hypoxemia worsens with P/F ratio less than 150 mmHg despite HFNC therapy, prompt endotracheal intubation should be performed. Predictors such as the ROX index or modified ROX index can guide the decision to switch from HFNC to invasive mechanical ventilation, but continuous monitoring of the patient's condition is necessary due to the difficulty of predicting patient prognosis based on these predictors alone. |

|

3-2. We suggest HFNC therapy as an alternative to invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure by COVID-19 when a decision has been made to discontinue life-sustaining treatments and there are no indications for invasive mechanical ventilation. |

Expert consensus |

|

Recommendations for pediatric care |

|

|

|

|

|

IVIG (alone or combined with steroids) for MIS-C patients |

Revision Jan 2023 |

1. For the initial treatment of patients with MIS-C, we suggest the use of IVIG combined with steroids rather than either IVIG alone or steroids alone. |

Very low |

B |

|

2. We consider the use of steroids alone for the initial treatment of patients with MIS-C. |

Expert consensus |

|

Other immunomodulators for MIS-C patients |

Revision Feb 2023 |

For patients with MIS-C who do not respond to IVIG and/or steroid therapy, we suggest the use of other immunomodulators (e.g., IL-1 inhibitor, IL-6 inhibitor, TNF-α inhibitor). |

Expert consensus |

|

Aspirin and anticoagulant therapy for MIS-C patients |

Revision Jan 2023 |

We suggest the use of low-dose aspirin to prevent thrombosis in patients with MIS-C. |

Expert consensus |

|

Medications for pediatric patients |

New Dec 2022 |

1. We suggest the use of remdesivir in pediatric patients (aged 28 days and over and weighing at least 3 kg) with severe COVID-19 who require supplemental oxygen without mechanical ventilation or ECMO. |

Expert consensus |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

We suggest treatment with five days of remdesivir in pediatric patients with severe COVID-19. If patients on remdesivir treatment progress to requiring mechanical ventilation or ECMO, the full course of remdesivir should still be completed. We recommend against the routine initiation of remdesivir in patients with COVID-19 on mechanical ventilation or ECMO. |

|

2. We suggest the use of remdesivir within seven days of symptom onset in pediatric patients (aged 12 yr and over and weighing at least 40 kg) with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 who do not require supplemental oxygen at high risk for progression to severe disease. |

Expert consensus |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

We suggest treatment with three days of remdesivir in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19. If these patients progress to severe COVID-19, five days of remdesivir treatment is suggested. |

|

3. We suggest the use of steroids (dexamethasone) in pediatric patients with severe-to-critical COVID-19 who require supplemental oxygen. |

Expert consensus |

|

4. In pediatric patients with severe or critical COVID-19 (≥ 2 yr of age), we consider the use of tocilizumab in addition to steroids. |

Expert consensus |

|

5. We suggest the use of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir in pediatric patients (aged 12 yr and over and weighing at least 40 kg) with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 at high risk for progression to severe disease. |

Low |

B |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

We recommend the use of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir within 5 days of symptom onset. |

|

Recommendation for emergency care |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mechanical CPR |

New Oct 2022 |

We suggest the use of mechanical CPR devices for cardiac arrest in patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 to mitigate the potential spread of infection through aerosols. |

Expert consensus |

|

Recommendations for diagnostic test |

|

|

|

|

|

Rapid antigen test (RAT) |

Revision Feb 2023 |

1. We recommend the rapid antigen test (RAT) be used in conjunction with the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for enhanced diagnostic accuracy |

Expert consensus |

|

2. For suspected COVID-19 cases, we generally do not recommend the RAT alone. However, as an exception, RAT may be used when the prevalence of COVID-19 increases and there are limitations in performing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests. |

Low |

C |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

While there are no significant differences in diagnostic accuracy based on virus variants, sensitivity tends to be lower in asymptomatic cases. However, additional studies are needed on newly emerging variants. |

|

Recommendations for radiological examinations |

|

|

|

|

|

Contrast-enhanced chest CT scan |

Revision Jan 2023 |

We suggest contrast-enhanced chest CT for patients with COVID-19 suspected of having a pulmonary embolism because of the elevated D-dimer level in a blood test and the presentation of suspicious symptoms, including dyspnea, hypoxia, and chest pain. |

Very low |

B |

|

Chest X-ray follow-up |

Retain Dec 2021 |

We suggest chest X-ray follow-ups for patients with COVID-19 during the treatment course and after isolation treatment. |

Very low |

B |

|

Chest CT using portable personal NPIC |

New Oct 2022 |

We suggest utilizing the portable personal NPIC for patients at high risk of COVID-19 transmission who require a clinically necessary chest CT scan. This allows for the safe conduct of the chest CT examination in a CT room that lacks a negative pressure isolation system. |

Expert consensus |

|

Clinical considerations: |

|

COVID-19 is an infectious disease with a high risk of droplet transmission. Therefore, performing CT without preparation can cause contamination of the scan room, leading to secondary infection cases. Accordingly, using a negative-pressure chamber to isolate the patient from the outside environment is recommended for CT scans. Interference with X-ray penetration and degradation of CT image quality due to the use of a portal personal NPIC are determined to be at a level that would still allow CT images to be interpreted. More specific recommendations need on the confirmation of results from various studies, including different NPIC types used in clinical practice, the severity of the disease, and CT scan methods. However, even if used a NIPC, the other routine processes, including disinfection, cleaning, and ventilation, are essential before and after the CT examination. |

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download