| Korean J Gastroenterol. 2017 Nov;70(5):253-260. English. Published online November 24, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4166/kjg.2017.70.5.253 | |

| Copyright © 2017. Korean Society of Gastroenterology | |

|

Myung Jin Oh | |

| Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, CHA Gumi Medical Center, CHA University School of Medicine, Gumi, Korea. | |

| Received August 07, 2017; Revised October 09, 2017; Accepted October 11, 2017. | |

|

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- | |

|

Abstract

| |

|

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome is one of the rare causes of small bowel obstruction. It develops following a marked decrease in the angle between SMA and the abdominal aorta due to weight loss, anatomical anomalies, or following surgeries. Nutcracker syndrome in the left renal vein may also occur following a decrease in the aortomesenteric angle. Though SMA syndrome and renal nutcracker syndrome share the same pathogenesis, concurrent development has rarely been reported. Herein, we report a 23-year-old healthy male diagnosed with SMA syndrome and renal nutcracker syndrome due to severe weight reduction. The patient visited our outpatient clinic presenting bilious vomiting and indigested vomitus for 3 consecutive days. He had lost 20 kg during military service. We suspected SMA syndrome based on abnormal air-shadow in the stomach and small bowel on abdominal X-ray; we confirmed compression of the third portion of the duodenum with upper gastrointestinal series and abdominal computed tomography (CT). Concurrently, renal nutcracker syndrome was also detected via abdominal CT and Doppler ultrasound. Considering bilious vomiting and no urinary symptoms, SMA syndrome was corrected by laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy, and close observation for the renal nutcracker syndrome was recommended. |

|

Keywords: Superior mesenteric artery syndrome; Renal nutcracker syndrome; Intestinal obstruction; Laparoscopic surgery |

|

|

INTRODUCTION

|

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome, or also known as Wilkie's syndrome, is a rare condition that can lead to upper gastrointestinal obstruction. It causes a compression on the third portion of the duodenum, due to a decreasing angle between the SMA and the abdominal aorta. Moreover, nutcracker syndrome in the left renal vein develops when the vein is trapped due to the same pathogenesis. Marked weight loss, anatomical variation, and surgical intervention can decrease the aortomesenteric angle.1 SMA syndrome and renal nutcracker syndrome are usually observed in females aged 10 to 40 years. Furthermore, both syndromes occurring concurrently is highly rare.2 Herein, we report on a healthy man in his 20s diagnosed with both SMA syndrome and renal nutcracker syndrome.

|

CASE REPORT

|

A 23-year-old male patient visited the outpatient clinic of our gastroenterology department presenting nausea and vomiting for 3 consecutive days. Three days before visitation, the patient had experienced abrupt-onset vomiting approximately 3 hours after a meal; on the following day, he had visited a local clinic and received treatment, but without improvement. The patient characteristically complained of bilious projectile vomiting, with partially indigested food material, and abdominal distension; he also explained he had often retched for the past year. He did not complain of other gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain and diarrhea. He had no specific past medical history, and he was not on any medication. The patient had undergone tonsillectomy 8 years ago. There was no problematic family history, except hypertension and diabetes. The patient had smoked for 5 pack years, but he did not drink alcohol.

The height and weight of our patient were 1.79 m and 66.2 kg, respectively, and his body mass index was 20.7 kg/m2. At the time of visitation, his blood pressure was 130/70 mmHg, pulse was 55 beats/min, respiration rate was 19 breaths/min, and body temperature was 36.7℃. On physical examination, he appeared acutely ill, with a soft and flat abdomen. We performed laboratory blood tests and plain abdominal X-ray exam. A complete blood count test showed a leukocyte count of 9,100 cells/mm3 (seg: 67.6 %), a hemoglobin level of 14.8 g/dL, and a platelet count of 228,000 cells/mm3. A blood chemistry test revealed total protein 7.0 g/dL, albumin 4.8 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen 17.2 mg/dL, creatinine 1.12 mg/dL, total bilirubin 1.2 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 14 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 12 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 55 IU/L, lactate dehydrogenase 132 IU/L, amylase 33 U/L, lipase 24 U/L, glucose 74 mg/dL, and an electrolyte level of Na+/K+/Cl−139/4.2/99 mEq/L. The level of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, an acute phase reactant, was 0.03 mg/dL, and his erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 2 mm/hr. A thyroid function test revealed 1.29 ng/dL of free T4 and 1.658 µIU/mL of thyroid stimulation hormone. We detected urine ketones of three positive; but we did not note hematuria or proteinuria in the spot urine test. Viral markers for hepatitis A, B, and C were all negative. Serum antibody to human immunodeficiency virus was also negative. An electrocardiogram revealed sinus bradycardia. On radiologic study of the abdomen, stomach contour was clearly radiolucent in the left upper quadrant of the supine image (Fig. 1). Beyond the second portion of the duodenum, a black air shadow was abruptly cut off in the same image.

|

We informed the patient that we suspected duodenal obstruction by peptic ulcer based on the clinical presentation and radiologic examination; however, he did not complain of any symptoms related to peptic ulcer, such as epigastric soreness and pre- or postprandial pain. Only then did he reveal that his body weight had decreased from 83 kg to 63 kg during his military service: The patient had served on the very front line of the demilitarized zone, and he had rarely eaten due to physical exhaustion. In spite of the rarity of the condition in a healthy young adult, we also considered the possibility of SMA syndrome. Thus, the patient was admitted for further examination for our suspicion of duodenal obstruction by peptic ulcer or SMA syndrome associated with extreme weight loss.

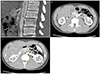

After admission, the patient vomited bilious contents continuously; despite the administration of anti-emetics, vomiting was not relieved. Thus, we performed contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) as quickly as possible. The CT scan showed an acute angle between the SMA and the abdominal aorta, with a value of 13.7° in the sagittal plane (Fig. 2A). The third portion of the duodenum was trapped between the SMA and the abdominal aorta, and the second portion and the proximal third portion of the duodenum were swollen (Fig. 2B). The distance between the abdominal aorta and SMA was 5.25 mm at the duodenum level. In addition, we noted a mild dilatation and tortuosity of the left renal vein because the two large vessels were trapped in the transverse plane of the scans (Fig. 2C). The distance between the abdominal aorta and SMA was 4.83 mm at the left renal vein level. The CT scan suggested the possibility of SMA syndrome and nutcracker syndrome in the left renal vein.

|

An esophagogastroduodenoscopic exam was performed before an upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series, and the endoscopic view showed luminal narrowing at the third portion of the duodenum in accordance with the heart beat (Fig. 3A). After the insertion of nasogastric tube to prevent aspiration of a contrast medium, we performed a UGI series with gastrograffin. According to the series images, less contrast in the third portion of the duodenum was observed; we also observed a proximal dilatation of the third portion of the duodenum (Fig. 4A). The cut-off sign for the UGI series clearly supported the diagnosis of SMA syndrome. In addition, a Doppler renal ultrasonography (US) was performed, and the scan showed that the ratio of the anteroposterior diameter of the left renal vein (the hilar to the aortomesenteric portion=9.54 mm/1.75 mm) was 5.45, and the ratio of peak velocity in the left renal vein between the aortomesenteric and hilar portions (112 cm/sec/25.6 cm/sec) was 4.38 (Fig. 5). We diagnosed the patient with simultaneous SMA syndrome and renal nutcracker syndrome.

|

|

|

Considering severe vomiting and the patient's demand for quick correction, we recommended immediate surgery for SMA syndrome, but no surgery was recommended for renal nutcracker syndrome because there was no pelvic or abdominal pain and no hematuria on urine analysis, and also because there was no thrombosis on an enhanced abdominal CT or Doppler US. Only laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy was performed for SMA syndrome. On the fourth post-operative day, we performed another UGI series before the patient began a new diet and checked for leakage; the series revealed no leakage of contrast and no particular abnormal findings at the anastomosis site (Fig. 4B). Moreover, on endoscopy, the third portion of the duodenum was observed more widely (Fig. 3B). On the fifth postoperative day the patient began a liquid diet; but the patient ate very slowly out of fear of vomiting. He was discharged as healthy with no complications on post-operative day 11.

|

DISCUSSION

|

SMA syndrome is a rare disease that can lead to small bowel obstruction. Its exact incidence is unknown, to the best of our knowledge. It decreases the aortomesenteric angle and aortomesenteric distance by obstructing the duodenum, and it is mainly observed in female adolescents. The normal aortomesenteric angle and distance range from 25° to 60° and from 10 mm to 28 mm,3, 4 respectively; in this case, the angle and distance were 13.7° and 5.25 mm, respectively. A number of factors can cause SMA syndrome, including malnutrition, human immunodeficiency virus infection, anorexia nervosa, malignancy, trauma, burn, and serious weight loss.1, 5 Moreover, rare causes of the syndrome include surgical intervention that distorts the anatomy and congenital shortness of the ligament of Treitz.6 In this case, given that the patient was a healthy adult male, it was important to consider the rapid weight loss of 20 kg from malnutrition and stress of being in the military as factors that could have contributed to the development of SMA syndrome. Appropriate diagnosis of SMA syndrome is challenging, and it is critical to note its clinical manifestations.

Frequent and severe vomiting by intestinal obstruction or ileus is known to cause electrolyte imbalance or hypokalemia and hypochloremia. In our case, we observed no electrolyte imbalance despite severe bilious vomiting in our patient; due to the young age and rapid onset of symptoms, his electrolytes might have compensated quickly. In this case, the only clue for suspicion of gastric outlet or duodenal obstruction was a plain abdominal X-ray. Recently, it seems that many physicians tend to overlook the basic radiologic examinations, such as plain abdomen and chest X-rays, and instead rely on US or abdominal CT scans. However, if US or abdominal CT scans are not readily available, plain X-rays of the abdomen can also reveal critical information, as in our case.

Conservative therapy, including gastric decompression and total parenteral nutrition or nasojejunal tube feeding, is usually recommended for SMA syndrome.2, 7 In general, surgery is attempted only if conservative management fails; conservative treatment is aimed at restoring of retroperitoneal fat and weight gain; however, it requires longer hospital stay and restricts daily activities. In our case, we gave the patient detailed information regarding conservative treatment and surgical intervention; because he was a newly hired employee, the patient wanted to avoid long hospital stay and refused a nasojejunal tube for feeding. After the patient and his parents carefully considered the pros and cons of medical or surgical treatment, and they selected the surgical procedure. The laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy that our patient underwent has a success rate over 90%.8 Other surgical procedures, include strong's procedure, which involves dividing the ligament of Treitz by mobilizing the duodenum, and gastrojejunostomy.9

In previous case reports, many patients with SMA syndrome presented at emergency departments with abrupt-onset bilious vomiting, as in this case; although SMA syndrome develops gradually due to the loss of visceral fat tissue, its definite symptoms may occur abruptly. It is assumed that there is a threshold for developing symptoms, and the threshold may be associated with luminal narrowing or elevated intraluminal pressure in the third portion of the duodenum. In general, SMA syndrome is diagnosed using either UGI series or abdominal CT. However, when symptoms like vomiting are present, intraluminal pressure in the narrow portion of the duodenum on endoscopy, if measure, it can also be used as a tool for diagnosis. In practice, upper endoscopic exams for dyspepsia or nausea and vomiting often reveal severe luminal narrowing of the third portion of the duodenum. Physicians can identify suspected SMA syndrome by measuring the intraluminal pressure in this situation.

Although both SMA and nutcracker syndromes can be diagnosed with the same condition, which is entrapment between the abdominal aorta and the SMA, they are considered different disease entities. Since El-Sadr and Mina in 1950 first described the compression of the left renal vein by the aorta and SMA, ‘nutcracker syndrome’ has been used interchangeably with ‘nutcracker phenomenon.’10 There are many diagnostic criteria for nutcracker syndrome/phenomenon, because variations of anatomy do not always cause serious clinical symptoms, as in this case. Ananthan et al. suggested that the term nutcracker syndrome should be limited to patients who present clinical symptoms and signs that include hematuria, proteinuria, flank pain, pelvic congestion in females, and varicoceles in males.11 They suggested that asymptomatic dilation of the left renal vein, as detected by CT scans or Doppler US, can be a normal variant or congenital variant. Although there were no clinical symptoms and signs, by using Kim et al.'s CT criteria for nutcracker syndrome, we were able to diagnose our case as SMA syndrome with nutcracker syndrome.12 CT criteria included narrowing of the left renal vein at the aortomesenteric portion (the so-called beak sign), ratio of the left renal vein diameter (hilar to aortomesenteric) ≥4.9, angle between the SMA and aorta <41°, and collateral venous circulation; furthermore, the US results of our patient supported the diagnosis of nutcracker syndrome. Kim et al. suggested that the ratio of anteroposterior diameter of the left renal vein ≥5.0 or the ratio of peak velocity of the left renal vein ≥5.0 on US might a viable marker for diagnosing nutcracker syndrome.13 In this case, although the ratio of peak velocity was below 5.0, the ratio of anteroposterior diameter of the left renal vein satisfied the US criterion of 5.45.

In addition, we searched the literature for previous case reports regarding concurrent occurrences of SMA and renal nutcracker syndromes. The summarized cases are shown in Table 1.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 In our case, the patient's body mass index was relatively high, and surgical intervention to treat SMA syndrome was used uniquely. In all cases, the specific therapy for renal nutcracker syndrome was not needed due to the lack of hematuria or serious urinary symptoms, and the symptoms related to SMA syndrome were well resolved after treatment.

|

Treatment for nutcracker syndrome remains controversial due to the different diagnostic criteria used in each report and the best therapeutic modalities are personalized. Gross hematuria and severe symptoms including flank or pelvic pain and renal impairment are the best indicators for surgical intervention.21, 22 We did not observe microscopic or macroscopic hematuria or renal impairment in this case, and a vascular surgeon recommended medical therapy or close observation. Weight gain after laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy may increase retroperitoneal adipose tissue and reduce tension in the left renal vein. Furthermore, other medical therapies for nutcracker syndrome may include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors to improve orthostatic proteinuria and aspirin to improve renal perfusion.23, 24

In conclusion, one of the rare causes for severe bilious vomiting may be SMA syndrome, even in a young adult male, and physicians should be mindful of the possibility of SMA syndrome, especially if the patient has significant weight loss; plain X-ray as well as abdominal CT or upper gastrointestinal series scan may have diagnostic value. It may be important to consider concurrent occurrence of renal nutcracker syndrome with the diagnosis of SMA syndrome.

|

Notes

|

Financial support:None.

Conflict of interest:None.

|

References

|

| 1. | Salem A, Al Ozaibi L, Nassif SMM, Osman RAGS, Al Abed NM, Badri FM. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: a diagnosis to be kept in mind (case report and literature review). Int J Surg Case Rep 2017;34:84–86. |

| 2. | Zaraket V, Deeb L. Wilkie's syndrome or superior mesenteric artery syndrome: fact or fantasy? Case Rep Gastroenterol 2015;9:194–199. |

| 3. | Cohen LB, Field SP, Sachar DB. The superior mesenteric artery syndrome. The disease that isn't, or is it? J Clin Gastroenterol 1985;7:113–116. |

| 4. | Kaur A, Pawar NC, Singla S, Mohi JK, Sharma S. Superior mesentric artery syndrome in a patient with subacute intestinal obstruction: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:TD03–TD05. |

| 5. | Albano MN, Costa Almeida C, Louro JM, Martinez G. Increase body weight to treat superior mesenteric artery syndrome. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017 pii: bcr-2017-219378.

|

| 6. | Louie PK, Basques BA, Bitterman A, et al. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome as a complication of scoliosis surgery. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2017;46:E124–E130. |

| 7. | Shiu JR, Chao HC, Luo CC, et al. Clinical and nutritional outcomes in children with idiopathic superior mesenteric artery syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2010;51:177–182. |

| 8. | Pillay Y. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: a case report of two surgical options, duodenal derotation and duodenojejunostomy. Case Rep Vasc Med 2016;2016:8301025. |

| 9. | Pourhassan S, Grotemeyer D, Fürst G, Rudolph J, Sandmann W. Infrarenal transposition of the superior mesenteric artery: a new approach in the surgical therapy for wilkie syndrome. J Vasc Surg 2008;47:201–204. |

| 10. | El-Sadr AR, Mina E. Anatomical and surgical aspects in the operative management of varicocele. Urol Cutaneous Rev 1950;54:257–262. |

| 11. | Ananthan K, Onida S, Davies AH. Nutcracker syndrome: an update on current diagnostic criteria and management guidelines. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2017;53:886–894. |

| 12. | Kim KW, Cho JY, Kim SH, et al. Diagnostic value of computed tomographic findings of nutcracker syndrome: correlation with renal venography and renocaval pressure gradients. Eur J Radiol 2011;80:648–654. |

| 13. | Kim SH, Cho SW, Kim HD, Chung JW, Park JH, Han MC. Nutcracker syndrome: diagnosis with Doppler US. Radiology 1996;198:93–97. |

| 14. | Pivawer G, Haller JO, Rabinowitz SS, Zimmerman DL. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome and its ramifications. CMIG Extra: Cases 2004;28:8–10. |

| 15. | Barsoum MK, Shepherd RF, Welch TJ. Patient with both wilkie syndrome and nutcracker syndrome. Vasc Med 2008;13:247–250. |

| 16. | Kim SH, Heo JU, Tang YK, et al. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome with nutcracker syndrome in a patient with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Korean J Med 2012;83:613–618. |

| 17. | Vulliamy P, Hariharan V, Gutmann J, Mukherjee D. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome and the ‘nutcracker phenomenon’. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013 pii: bcr2013008734.

|

| 18. | Inal M, Unal Daphan B, Karadeniz Bilgili MY. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome accompanying with nutcracker syndrome: a case report. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014;16:e14755 |

| 19. | Nunn R, Henry J, Slesser AA, Fernando R, Behar N. A model example: coexisting superior mesenteric artery syndrome and the nutcracker phenomenon. Case Rep Surg 2015;2015:649469. |

| 20. | Iqbal S, Siddique K, Saeed U, Khan ZA, Ahmad S. Nutcracker phenomenon with wilkie's syndrome in a patient with rectal cancer. J Med Cases 2016;7:282–285. |

| 21. | Said SM, Gloviczki P, Kalra M, et al. Renal nutcracker syndrome: surgical options. Semin Vasc Surg 2013;26:35–42. |

| 22. | Zhang H, Li M, Jin W, San P, Xu P, Pan S. The left renal entrapment syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Ann Vasc Surg 2007;21:198–203. |

| 23. | Hosotani Y, Kiyomoto H, Fujioka H, Takahashi N, Kohno M. The nutcracker phenomenon accompanied by renin-dependent hypertension. Am J Med 2003;114:617–618. |

| 24. | He Y, Wu Z, Chen S, et al. Nutcracker syndrome--how well do we know it? Urology 2014;83:12–17. |

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print