1. GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019; 393:1958–1972. PMID:

30954305.

2. Okayama A, Okuda N, Miura K, Okamura T, Hayakawa T, Akasaka H, Ohnishi H, Saitoh S, Arai Y, Kiyohara Y, et al. Dietary sodium-to-potassium ratio as a risk factor for stroke, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in Japan: the NIPPON DATA80 cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016; 6:e011632.

3. Mente A, O'Donnell M, Rangarajan S, McQueen M, Dagenais G, Wielgosz A, Lear S, Ah ST, Wei L, Diaz R, et al. Urinary sodium excretion, blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: a community-level prospective epidemiological cohort study. Lancet. 2018; 392:496–506. PMID:

30129465.

4. Li Y, Huang Z, Jin C, Xing A, Liu Y, Huangfu C, Lichtenstein AH, Tucker KL, Wu S, Gao X. Longitudinal change of perceived salt intake and stroke risk in a Chinese population. Stroke. 2018; 49:1332–1339. PMID:

29739913.

5. Umesawa M, Iso H, Fujino Y, Kikuchi S, Tamakoshi A. JACC Study Group. Salty food preference and intake and risk of gastric cancer: the JACC Study. J Epidemiol. 2016; 26:92–97. PMID:

26477994.

6. Deckers IA, van Engeland M, van den Brandt PA, Van Neste L, Soetekouw PM, Aarts MJ, Baldewijns MM, Keszei AP, Schouten LJ. Promoter CpG island methylation in ion transport mechanisms and associated dietary intakes jointly influence the risk of clear-cell renal cell cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46:622–631. PMID:

27789672.

7. Faraco G, Hochrainer K, Segarra SG, Schaeffer S, Santisteban MM, Menon A, Jiang H, Holtzman DM, Anrather J, Iadecola C. Dietary salt promotes cognitive impairment through tau phosphorylation. Nature. 2019; 574:686–690. PMID:

31645758.

8. Horikawa C, Yoshimura Y, Kamada C, Tanaka S, Tanaka S, Hanyu O, Araki A, Ito H, Tanaka A, Ohashi Y, et al. Dietary sodium intake and incidence of diabetes complications in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: analysis of the Japan Diabetes Complications Study (JDCS). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014; 99:3635–3643. PMID:

25050990.

9. Suzuki A, Katoh H, Komura D, Kakiuchi M, Tagashira A, Yamamoto S, Tatsuno K, Ueda H, Nagae G, Fukuda S, et al. Defined lifestyle and germline factors predispose Asian populations to gastric cancer. Sci Adv. 2020; 6:eaav9778. PMID:

32426482.

10. Shin SJ, Lim CY, Rhee MY, Oh SW, Na SH, Park Y, Kim CI, Kim SY, Kim JW, Park HK. Characteristics of sodium sensitivity in Korean populations. J Korean Med Sci. 2011; 26:1061–1067. PMID:

21860557.

11. Merino J, Guasch-Ferré M, Martínez-González MA, Corella D, Estruch R, Fitó M, Ros E, Arós F, Bulló M, Gómez-Gracia E, et al. Is complying with the recommendations of sodium intake beneficial for health in individuals at high cardiovascular risk? Findings from the PREDIMED study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015; 101:440–448. PMID:

25733627.

14. Breslin PA. An evolutionary perspective on food and human taste. Curr Biol. 2013; 23:R409–R418. PMID:

23660364.

15. Puska P, Vartiainen E, Tuomilehto J, Salomaa V, Nissinen A. Changes in premature deaths in Finland: successful long-term prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Bull World Health Organ. 1998; 76:419–425. PMID:

9803593.

16. Holdsworth M, Haslam C, Raymond NT. Does the heartbeat award scheme change employees' dietary attitudes and knowledge? Appetite. 2000; 35:179–188. PMID:

10986111.

17. He FJ, Brinsden HC, MacGregor GA. Salt reduction in the United Kingdom: a successful experiment in public health. J Hum Hypertens. 2014; 28:345–352. PMID:

24172290.

23. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Korea Health Statistics 2020: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VIII-2) [Internet]. Cheongjusi: Ministry of Health and Welfare.

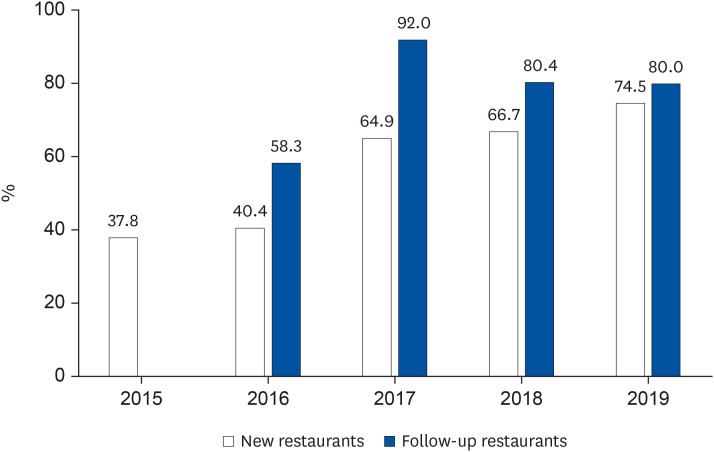

24. Ma J, Lee S, Kim K, Lee YK. Sodium reduction in South Korean restaurants: a Daegu-based intervention project. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2020; 29:404–413. PMID:

32674248.

26. Moran AJ, Ramirez M, Block JP. Consumer underestimation of sodium in fast food restaurant meals: results from a cross-sectional observational study. Appetite. 2017; 113:155–161. PMID:

28235618.

27. Nakadate M, Ishihara J, Iwasaki M, Kitamura K, Kato E, Tanaka J, Nakamura K, Ishihara T, Shintani A, Takachi R. Effect of monitoring salt concentration of home-prepared dishes and using low-sodium seasonings on sodium intake reduction. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018; 72:1413–1420. PMID:

29321686.

28. Kim SH, Kim MS, Lee MS, Park YS, Lee HJ, Kang S, Lee HS, Lee KE, Yang HJ, Kim MJ, et al. Korean diet: characteristics and historical background. J Ethn Food. 2016; 3:26–31.

29. Shim E, Ryu HJ, Hwang J, Kim SY, Chung EJ. Dietary sodium intake in young Korean adults and its relationship with eating frequency and taste preference. Nutr Res Pract. 2013; 7:192–198. PMID:

23766880.

30. Bobowski N. Shifting human salty taste preference: potential opportunities and challenges in reducing dietary salt intake of Americans. Chemosens Percept. 2015; 8:112–116. PMID:

26451233.

31. Lee J, Park S. Management of sodium-reduced meals at worksite cafeterias: perceptions, practices, barriers, and needs among food service personnel. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2016; 7:119–126. PMID:

27169011.

32. Musicus AA, Moran AJ, Lawman HG, Roberto CA. Online randomized controlled trials of restaurant sodium warning labels. Am J Prev Med. 2019; 57:e181–e193. PMID:

31753271.

33. Wolfson JA, Moran AJ, Jarlenski MP, Bleich SN. Trends in sodium content of menu items in large chain restaurants in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2018; 54:28–36. PMID:

29056370.

34. Murphy SA, Weippert MV, Dickinson KM, Scourboutakos MJ, L'Abbé MR. Cross-sectional analysis of calories and nutrients of concern in Canadian chain restaurant menu items in 2016. Am J Prev Med. 2020; 59:e149–e159. PMID:

32828587.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download