INTRODUCTION

Uganda is experiencing malnutrition in both the adult and under-five-year old populations. The prevalences of overweight and obesity are also rapidly increasing, with a large sex disparity. According to the 2016 non-communicable disease (NCD) collaboration report, 30.9% of women were overweight and 8.6% were obese, compared with 13.7% and 1.8% of men [

1]. There is a strong link between NCDs, and overweight and obesity. Obesity and overweight increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, kidney disease, certain types of cancer, and musculoskeletal disorders [

23].

Dietary intake is an important predictor of high body mass index (BMI). As observed in other East African countries, a shift in dietary patterns from indigenous and traditional dietary habits-termed as the nutrition transition could partly explain the obesity epidemic in Uganda. In 2014, Steyn and colleagues predicted that among other factors, increase in energy, fat, and sugar intake in the next years would strongly be associated with overweight and obesity in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [

2]. Furthermore, available evidence suggests that a shift from a traditional diet high in carbohydrates and fiber and low in fat and sugar to a Western diet high in energy, saturated fat, sodium, and sugar; and low in fiber, increases the risk of obesity and other NCDs [

4].

Eating away from home (EAFH) is one of the dietary behaviors associated with the consumption of diets high in energy, fat, sugar, and salt; and low in fruits and vegetables. Also, available evidence suggests that EAFH contributes to obesity [

5]. EAFH is becoming increasingly popular in Uganda due to changing demographic trends. In particular, the working class now prefer EAFH to eating at home [

6]. The prevalence of EAFH has been reported to be 39.2% in Uganda, and reportedly, 69.5% of men and 30.5% of women eat ≥ 3 meals away from home per week [

7], which underscores the importance of this eating behavior in Uganda.

EAFH includes all meals (breakfast, lunch, or dinner) that were prepared and eaten outside the consumer’s home. In Uganda, non-home prepared foods include street foods, foods eaten at full-service restaurants, hotels, kiosks, and workplace canteens. In this paper, we examined EAFH regardless of the type of establishment. The contribution of EAFH to dietary intake in Uganda has not been extensively studied, but reports indicate that street foods contribute 49.1% to daily fat intake, 38.4% to daily sodium intake, and little to vitamin A intake in urban areas [

8]. These results indicate that street foods comprise excess fat and salt, but little fruits and vegetables, and may predispose individuals to the development of NCDs.

Given the trend towards EAFH and the recognized impact of EAFH on BMI, research on the influence of this dietary behavior on obesity and overweight is warranted. Identifying the influence of EAFH on overweight and obesity would facilitate the development of nutritional and lifestyle interventions targeting obesity prevention. Researchers elsewhere have reported on the associations between EAFH and overweight and obesity. Some reported positive associations [

9101112], while others reported no significant associations [

13], or positive associations in men, but negative associations in women [

9].

Nonetheless, no study has examined the relationships between EAFH and overweight or obesity in Uganda. In this study, we used nationally representative data from the 2014 Uganda NCD risk factor baseline survey to examine the associations between EAFH and overweight and obesity among Ugandan adults, and to determine whether these associations differ by sex and age.

Go to :

RESULTS

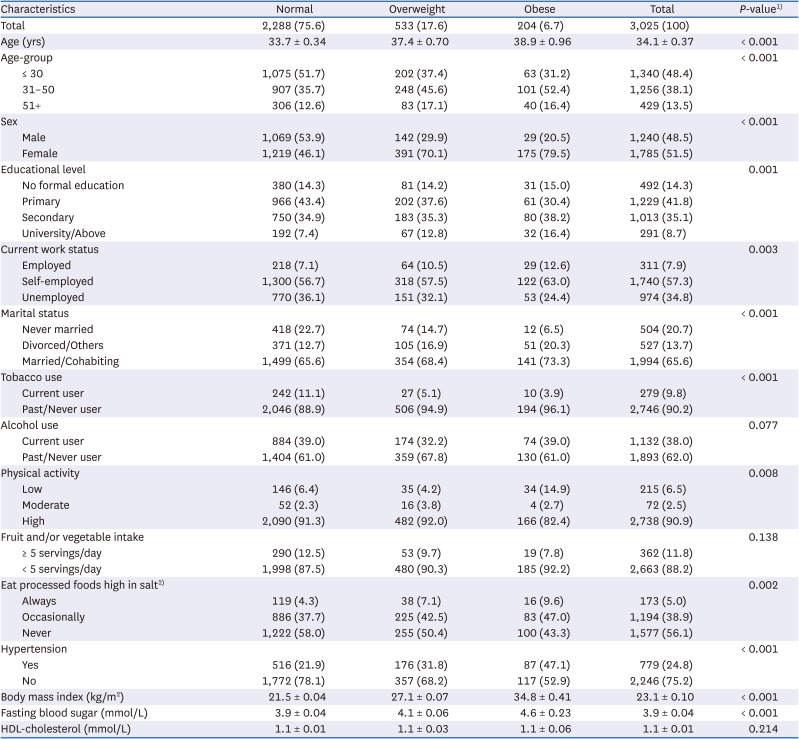

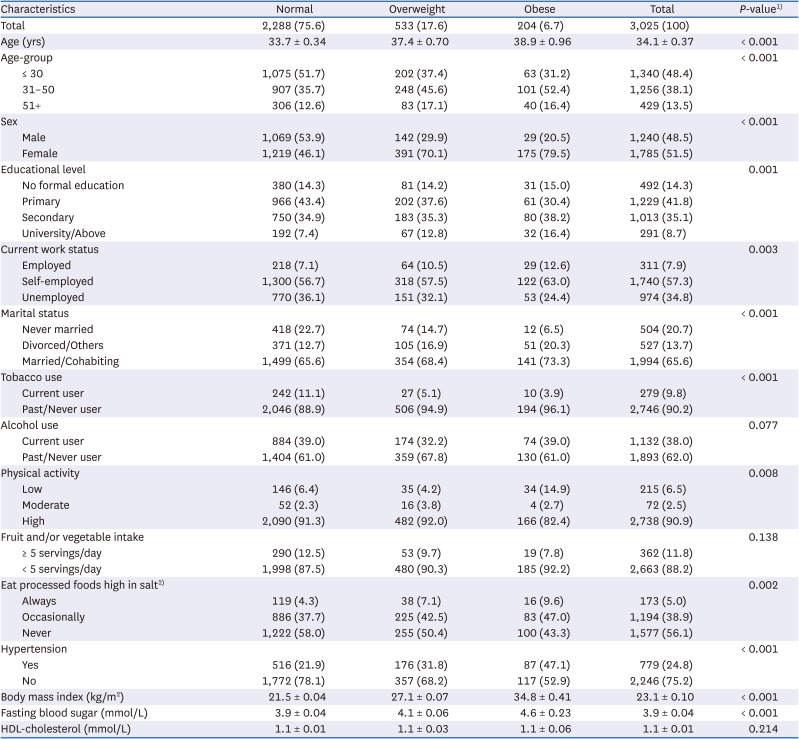

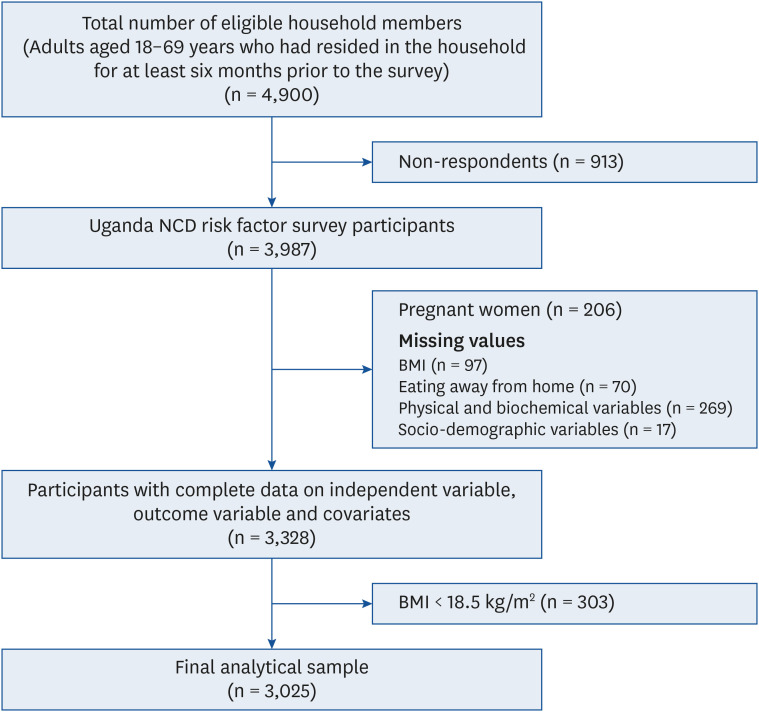

General characteristics of the study participants are presented in

Table 1. In total, 3,025 study participants (1,785 women and 1,240 men) with a mean age of 34.1 years and mean BMI of 23.1 kg/m

2 were studied. Women accounted for 70.1%, 79.5%, and 46.1% of participants in the overweight, obese, and normal body weight groups respectively (

P < 0.001). For participants aged 31–50 years, 35.7% had a normal body weight, and 45.6% and 52.4% were overweight and obese respectively (

P < 0.001). The respective percentages of normal, overweight, and obese for each characteristic are as follows: had a university degree and above 7.4%, 12.8%, and 16.4% (

P = 0.001), employed 7.1%, 10.5%, and 12.6% (

P = 0.003), married or cohabiting 65.6%, 68.4%, and 73.3% (

P < 0.001), tobacco past/never users 88.9%, 94.9%, and 96.1% (

P < 0.001). The percentages of obese and normal weight participants with low physical activity were 14.9% and 6.4%, respectively (

P = 0.008). Among those who always ate processed foods high in salt, 7.1% were overweight and 9.6% were obese compared with 4.3% of those with a normal body weight (

P = 0.002). The prevalence of hypertension was 21.9%, 31.8%, and 47.1%, (

P < 0.001), and the mean BMI was 21.5 ± 0.04, 27.1 ± 0.07 and 34.8 ± 0.41 kg/m

2 in the normal body weight, overweight, and obese groups, respectively. The mean fasting blood sugar was significantly higher in the overweight (4.1 ± 0.06 mmol/L) and obese (4.6 ± 0.2 mmol/L) groups than in the normal body weight group (3.9 ± 0.5 mmol/L) (

P < 0.001).

Table 1

Characteristics of study participants according to body weight status

|

Characteristics |

Normal |

Overweight |

Obese |

Total |

P-value1)

|

|

Total |

2,288 (75.6) |

533 (17.6) |

204 (6.7) |

3,025 (100) |

|

|

Age (yrs) |

33.7 ± 0.34 |

37.4 ± 0.70 |

38.9 ± 0.96 |

34.1 ± 0.37 |

< 0.001 |

|

Age-group |

|

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

≤ 30 |

1,075 (51.7) |

202 (37.4) |

63 (31.2) |

1,340 (48.4) |

|

31–50 |

907 (35.7) |

248 (45.6) |

101 (52.4) |

1,256 (38.1) |

|

51+ |

306 (12.6) |

83 (17.1) |

40 (16.4) |

429 (13.5) |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Male |

1,069 (53.9) |

142 (29.9) |

29 (20.5) |

1,240 (48.5) |

|

Female |

1,219 (46.1) |

391 (70.1) |

175 (79.5) |

1,785 (51.5) |

|

Educational level |

|

|

|

|

0.001 |

|

No formal education |

380 (14.3) |

81 (14.2) |

31 (15.0) |

492 (14.3) |

|

Primary |

966 (43.4) |

202 (37.6) |

61 (30.4) |

1,229 (41.8) |

|

Secondary |

750 (34.9) |

183 (35.3) |

80 (38.2) |

1,013 (35.1) |

|

University/Above |

192 (7.4) |

67 (12.8) |

32 (16.4) |

291 (8.7) |

|

Current work status |

|

|

|

|

0.003 |

|

Employed |

218 (7.1) |

64 (10.5) |

29 (12.6) |

311 (7.9) |

|

Self-employed |

1,300 (56.7) |

318 (57.5) |

122 (63.0) |

1,740 (57.3) |

|

Unemployed |

770 (36.1) |

151 (32.1) |

53 (24.4) |

974 (34.8) |

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Never married |

418 (22.7) |

74 (14.7) |

12 (6.5) |

504 (20.7) |

|

Divorced/Others |

371 (12.7) |

105 (16.9) |

51 (20.3) |

527 (13.7) |

|

Married/Cohabiting |

1,499 (65.6) |

354 (68.4) |

141 (73.3) |

1,994 (65.6) |

|

Tobacco use |

|

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Current user |

242 (11.1) |

27 (5.1) |

10 (3.9) |

279 (9.8) |

|

Past/Never user |

2,046 (88.9) |

506 (94.9) |

194 (96.1) |

2,746 (90.2) |

|

Alcohol use |

|

|

|

|

0.077 |

|

Current user |

884 (39.0) |

174 (32.2) |

74 (39.0) |

1,132 (38.0) |

|

Past/Never user |

1,404 (61.0) |

359 (67.8) |

130 (61.0) |

1,893 (62.0) |

|

Physical activity |

|

|

|

|

0.008 |

|

Low |

146 (6.4) |

35 (4.2) |

34 (14.9) |

215 (6.5) |

|

Moderate |

52 (2.3) |

16 (3.8) |

4 (2.7) |

72 (2.5) |

|

High |

2,090 (91.3) |

482 (92.0) |

166 (82.4) |

2,738 (90.9) |

|

Fruit and/or vegetable intake |

|

|

|

|

0.138 |

|

≥ 5 servings/day |

290 (12.5) |

53 (9.7) |

19 (7.8) |

362 (11.8) |

|

< 5 servings/day |

1,998 (87.5) |

480 (90.3) |

185 (92.2) |

2,663 (88.2) |

|

Eat processed foods high in salt2)

|

|

|

|

|

0.002 |

|

Always |

119 (4.3) |

38 (7.1) |

16 (9.6) |

173 (5.0) |

|

Occasionally |

886 (37.7) |

225 (42.5) |

83 (47.0) |

1,194 (38.9) |

|

Never |

1,222 (58.0) |

255 (50.4) |

100 (43.3) |

1,577 (56.1) |

|

Hypertension |

|

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Yes |

516 (21.9) |

176 (31.8) |

87 (47.1) |

779 (24.8) |

|

No |

1,772 (78.1) |

357 (68.2) |

117 (52.9) |

2,246 (75.2) |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

21.5 ± 0.04 |

27.1 ± 0.07 |

34.8 ± 0.41 |

23.1 ± 0.10 |

< 0.001 |

|

Fasting blood sugar (mmol/L) |

3.9 ± 0.04 |

4.1 ± 0.06 |

4.6 ± 0.23 |

3.9 ± 0.04 |

< 0.001 |

|

HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) |

1.1 ± 0.01 |

1.1 ± 0.03 |

1.1 ± 0.06 |

1.1 ± 0.01 |

0.214 |

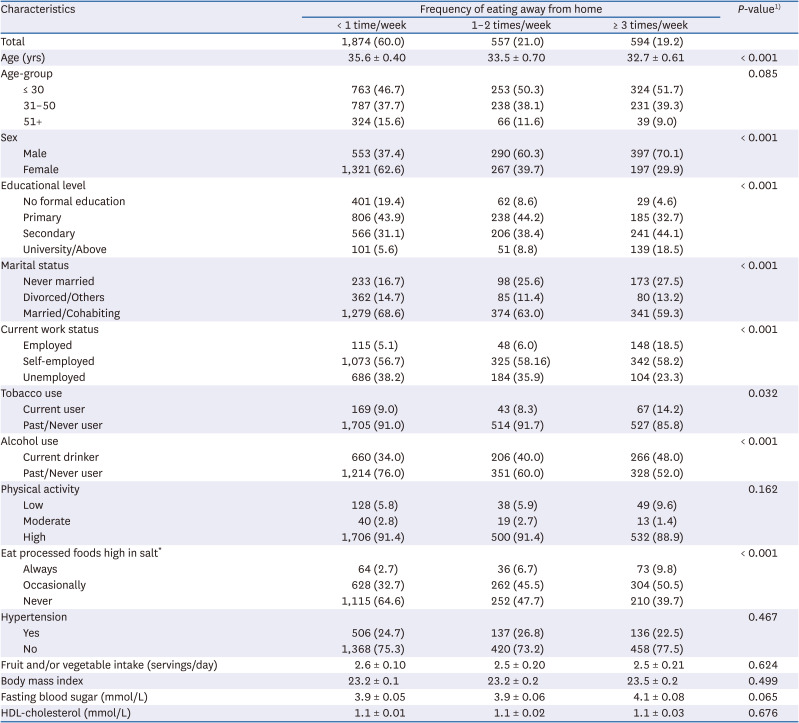

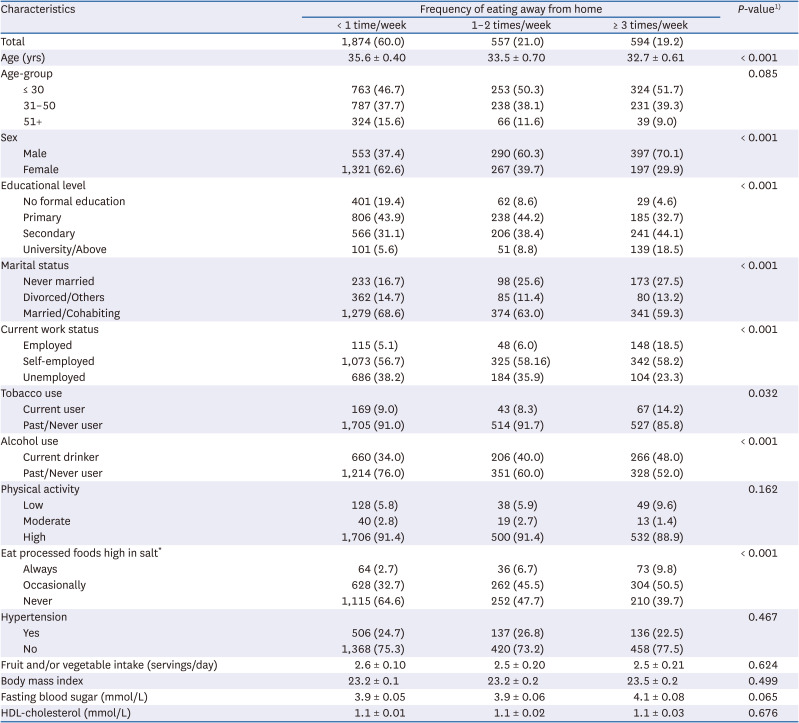

Table 2 presents the frequencies of EAFH and characteristics of the study participants. Most of the participants that ate away from home ≥ 3 times/week were men (70.1%,

P < 0.001). Among those who ate away from home ≥ 3 times/week, 18.5% had at least a university degree compared with 5.6% of those that ate away from home less than once/week (

P < 0.001). The respective percentages of participants that ate away from home ≥ 3 times/week and less than once/week were distributed as follows: married 59.3% and 68.6% (

P < 0.001); employed 18.5% and 5.1% (

P < 0.001); current tobacco users 14.2% and 9.0% (

P < 0.05); current alcohol users 48.0% and 34.0% (

P < 0.001); and always ate processed foods high in salt 9.8% and 2.7%, respectively (

P < 0.001).

Table 2

Characteristics of study participants according to the frequency of eating away from home

|

Characteristics |

Frequency of eating away from home |

P-value1)

|

|

< 1 time/week |

1–2 times/week |

≥ 3 times/week |

|

Total |

1,874 (60.0) |

557 (21.0) |

594 (19.2) |

|

|

Age (yrs) |

35.6 ± 0.40 |

33.5 ± 0.70 |

32.7 ± 0.61 |

< 0.001 |

|

Age-group |

|

|

|

0.085 |

|

≤ 30 |

763 (46.7) |

253 (50.3) |

324 (51.7) |

|

31–50 |

787 (37.7) |

238 (38.1) |

231 (39.3) |

|

51+ |

324 (15.6) |

66 (11.6) |

39 (9.0) |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Male |

553 (37.4) |

290 (60.3) |

397 (70.1) |

|

Female |

1,321 (62.6) |

267 (39.7) |

197 (29.9) |

|

Educational level |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

No formal education |

401 (19.4) |

62 (8.6) |

29 (4.6) |

|

Primary |

806 (43.9) |

238 (44.2) |

185 (32.7) |

|

Secondary |

566 (31.1) |

206 (38.4) |

241 (44.1) |

|

University/Above |

101 (5.6) |

51 (8.8) |

139 (18.5) |

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Never married |

233 (16.7) |

98 (25.6) |

173 (27.5) |

|

Divorced/Others |

362 (14.7) |

85 (11.4) |

80 (13.2) |

|

Married/Cohabiting |

1,279 (68.6) |

374 (63.0) |

341 (59.3) |

|

Current work status |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Employed |

115 (5.1) |

48 (6.0) |

148 (18.5) |

|

Self-employed |

1,073 (56.7) |

325 (58.16) |

342 (58.2) |

|

Unemployed |

686 (38.2) |

184 (35.9) |

104 (23.3) |

|

Tobacco use |

|

|

|

0.032 |

|

Current user |

169 (9.0) |

43 (8.3) |

67 (14.2) |

|

Past/Never user |

1,705 (91.0) |

514 (91.7) |

527 (85.8) |

|

Alcohol use |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Current drinker |

660 (34.0) |

206 (40.0) |

266 (48.0) |

|

Past/Never user |

1,214 (76.0) |

351 (60.0) |

328 (52.0) |

|

Physical activity |

|

|

|

0.162 |

|

Low |

128 (5.8) |

38 (5.9) |

49 (9.6) |

|

Moderate |

40 (2.8) |

19 (2.7) |

13 (1.4) |

|

High |

1,706 (91.4) |

500 (91.4) |

532 (88.9) |

|

Eat processed foods high in salt*

|

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Always |

64 (2.7) |

36 (6.7) |

73 (9.8) |

|

Occasionally |

628 (32.7) |

262 (45.5) |

304 (50.5) |

|

Never |

1,115 (64.6) |

252 (47.7) |

210 (39.7) |

|

Hypertension |

|

|

|

0.467 |

|

Yes |

506 (24.7) |

137 (26.8) |

136 (22.5) |

|

No |

1,368 (75.3) |

420 (73.2) |

458 (77.5) |

|

Fruit and/or vegetable intake (servings/day) |

2.6 ± 0.10 |

2.5 ± 0.20 |

2.5 ± 0.21 |

0.624 |

|

Body mass index |

23.2 ± 0.1 |

23.2 ± 0.2 |

23.5 ± 0.2 |

0.499 |

|

Fasting blood sugar (mmol/L) |

3.9 ± 0.05 |

3.9 ± 0.06 |

4.1 ± 0.08 |

0.065 |

|

HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) |

1.1 ± 0.01 |

1.1 ± 0.02 |

1.1 ± 0.03 |

0.676 |

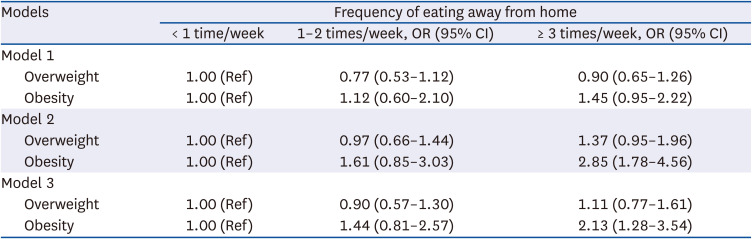

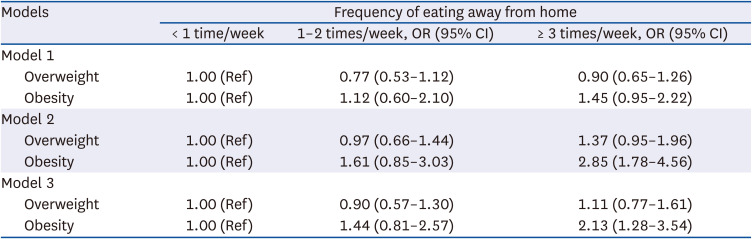

The ORs and 95% CIs of the associations between EAFH and obesity and overweight are presented in

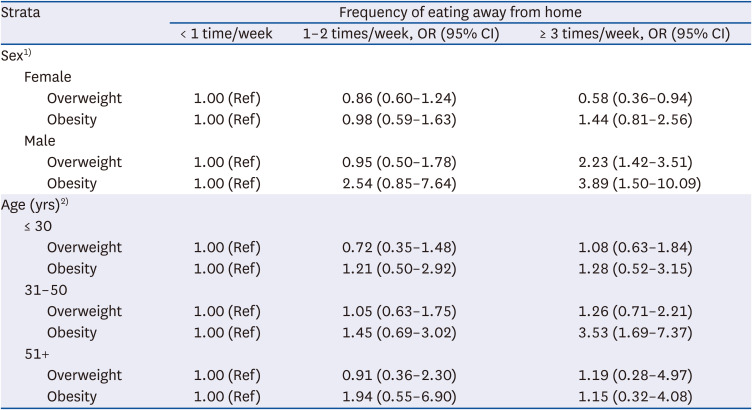

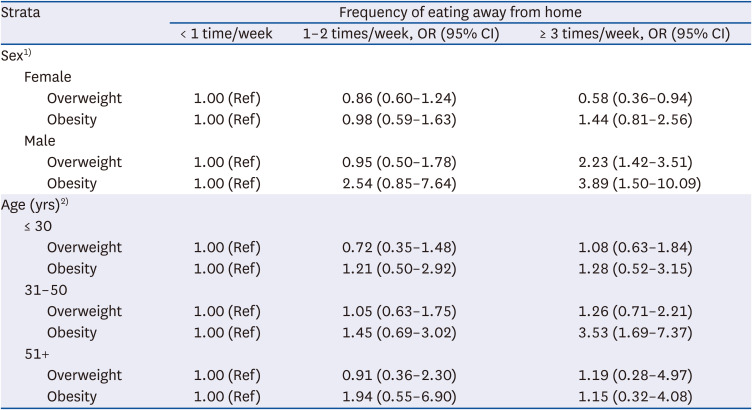

Table 3. EAFH ≥ 3 times/week was positively associated with obesity but not overweight. In the age and sex-adjusted model (model 2), those who ate away from home ≥ 3 times/week were 2.13 times more likely to be obese (OR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.28–3.54) than those that ate away from home less than once/week. In the fully adjusted model, the odds of being obese were 2.17 times greater in those who ate away from home ≥ 3 times/week than those that ate away from home less than once/week (OR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.28–3.65). However, stratified analyses (

Table 4) showed that women that ate away from home ≥ 3 times/week were 42% less likely to be overweight than those that ate away from home less than once/week (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.36–0.94). In contrast, EAFH ≥ 3 times/week was positively associated with overweight and obesity in men. Men that ate away from home ≥ 3 times/week were 2.23 and 3.89 times more likely to be overweight and obese, respectively, than those that ate away from home less than once/week (OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.42–3.51 and OR, 3.89; 95% CI, 1.50–10.09, respectively) (

Table 4). Age-stratified analyses showed that EAFH ≥ 3 times a week was positively associated with obesity among participants aged 31–50 years. Those that ate away from home ≥ 3 times a week were 3.53 times more likely to be obese than those that ate away from home less than once/week (OR, 3.53; 95% CI, 1.69–7.37).

Table 3

Associations between eating away from home and overweight and obesity

|

Models |

Frequency of eating away from home |

|

< 1 time/week |

1–2 times/week, OR (95% CI) |

≥ 3 times/week, OR (95% CI) |

|

Model 1 |

|

|

|

|

Overweight |

1.00 (Ref) |

0.77 (0.53–1.12) |

0.90 (0.65–1.26) |

|

Obesity |

1.00 (Ref) |

1.12 (0.60–2.10) |

1.45 (0.95–2.22) |

|

Model 2 |

|

|

|

|

Overweight |

1.00 (Ref) |

0.97 (0.66–1.44) |

1.37 (0.95–1.96) |

|

Obesity |

1.00 (Ref) |

1.61 (0.85–3.03) |

2.85 (1.78–4.56) |

|

Model 3 |

|

|

|

|

Overweight |

1.00 (Ref) |

0.90 (0.57–1.30) |

1.11 (0.77–1.61) |

|

Obesity |

1.00 (Ref) |

1.44 (0.81–2.57) |

2.13 (1.28–3.54) |

Table 4

Associations between eating away from home and obesity and overweight stratified by sex and age

|

Strata |

Frequency of eating away from home |

|

< 1 time/week |

1–2 times/week, OR (95% CI) |

≥ 3 times/week, OR (95% CI) |

|

Sex1)

|

|

|

|

|

Female |

|

|

|

|

|

Overweight |

1.00 (Ref) |

0.86 (0.60–1.24) |

0.58 (0.36–0.94) |

|

|

Obesity |

1.00 (Ref) |

0.98 (0.59–1.63) |

1.44 (0.81–2.56) |

|

Male |

|

|

|

|

|

Overweight |

1.00 (Ref) |

0.95 (0.50–1.78) |

2.23 (1.42–3.51) |

|

|

Obesity |

1.00 (Ref) |

2.54 (0.85–7.64) |

3.89 (1.50–10.09) |

|

Age (yrs)2)

|

|

|

|

|

≤ 30 |

|

|

|

|

|

Overweight |

1.00 (Ref) |

0.72 (0.35–1.48) |

1.08 (0.63–1.84) |

|

|

Obesity |

1.00 (Ref) |

1.21 (0.50–2.92) |

1.28 (0.52–3.15) |

|

31–50 |

|

|

|

|

|

Overweight |

1.00 (Ref) |

1.05 (0.63–1.75) |

1.26 (0.71–2.21) |

|

|

Obesity |

1.00 (Ref) |

1.45 (0.69–3.02) |

3.53 (1.69–7.37) |

|

51+ |

|

|

|

|

|

Overweight |

1.00 (Ref) |

0.91 (0.36–2.30) |

1.19 (0.28–4.97) |

|

|

Obesity |

1.00 (Ref) |

1.94 (0.55–6.90) |

1.15 (0.32–4.08) |

Go to :

DISCUSSION

We examined the associations between EAFH and overweight and obesity in a nationally representative sample of Ugandan adults. In this population, we found a positive association between EAFH and obesity. However, this association was modified by sex and age. Frequent EAFH was positively associated with overweight and obesity in men, and obesity among the 31–50-year-olds, but negatively associated with overweight in women.

The positive associations between EAFH and overweight and obesity suggest that away-from-home food restaurants are offering unhealthy dietary options. No previous study has examined the relationships between EAFH and overweight and obesity in Uganda, but these relationships have been examined in other countries. EAFH was positively associated with obesity and overweight among Brazilian men [

9]. In another study, EAFH was associated with higher BMI among adults [

22], and in a review study, researchers concluded that EAFH was positively associated with bodyweight [

10]. Furthermore, recent studies also concluded that EAFH was associated with obesity [

1112]. Although other mechanisms such as decreased energy expenditure evidently contribute, obesity results from a positive energy balance secondary to excessive food consumption, and specifically, the consumption of large portion sizes of energy-dense foods [

232425].

The dietary and nutrient compositions of meals eaten away from home could explain the positive associations between EAFH and overweight and obesity. EAFH is associated with the consumption of foods that are high in energy, fat, sugar, and salt, but low in fruits, vegetables, and micronutrients [

5826]. Orfanous and colleagues reported that EAFH was associated with excessive energy intake and lower physical activity, which are both risk factors of weight gain [

13]. Eating more fast foods was linked to excessive calorie intake and subsequent risk of weight gain [

27]. In Uganda, street foods, one of the most popular types of foods eaten away from home, contribute more energy and carbohydrates, but less micronutrients than home-prepared foods [

28] suggesting a low dietary quality of these foods and their potential contribution to obesity.

The positive associations between EAFH and obesity, and overweight in men is consistent with previous reports [

9]. Our findings suggest that when EAFH, men choose dietary items that predispose to excess weight gain. We also found that men ate away from home more frequently than women. Culturally, this can be explained by the fact that women are responsible for food preparation in Uganda. Previous studies have reported that in urban areas of Uganda, more men eat at street food establishments than women [

8], which suggests that men are more susceptible than women to the dietary deficiencies and/or excesses of away-from-home foods. In one recent Ugandan study, men consumed more energy and fat from street foods than women [

8], which concurs with the findings of a Kenyan study [

29]. Although street foods and kiosks are the most popular sources of away-from-home foods, further research is needed to determine the differential and independent contributions of various types of away-from-home meals to overall dietary and nutrient intake among Ugandan men. Furthermore, public health campaigns targeting men could encourage them to choose home-prepared meals. However, whether home-prepared meals in Uganda differ from away-from-home meals in terms of energy, macronutrient, and micronutrient compositions is not known and warrants further investigations. Nevertheless, preparing meals at home is associated with consumption of a healthier diet [

30], and young adults that prepared their food more frequently consumed fewer fast-foods and had a better diet quality [

31].

We found a negative association between EAFH and overweight in women, which is consistent with previous findings [

9]. Specifically, eating meals at sit-down restaurants was inversely associated with obesity in women [

9], and the authors of that study suggested that women select healthier options when EAFH. In Korea, middle-aged housewives consider the health benefits of away-from-home meals more important than not EAFH per se, and eating out frequency was related to frequent fruit intake in this sub-population [

32]. In contrast, take-away foods were positively associated with increased BMI [

11], and fast-food restaurants were associated with higher energy and fat intake and increased body weight in women [

33]. Observed differences between study findings could reflect different study designs, populations, and different methods of evaluating EAFH.

Urbanization, changing socioeconomic status, women empowerment, and increasing educational attainment in Uganda could be drivers of away-from-home eating. In the present study, frequent consumers of away-from-home meals tended to be more educated, employed or self-employed, and younger than rare consumers, which is consistent with previous studies [

3234]. Socio-demographic factors also influence consumers’ choices of the type of away-from-home food establishments. For example, street foods are considered an important source of diet by the urban and rural poor in Uganda, as is the case in other developing countries [

828]. In Kenya, street foods are frequently consumed in low-income slum areas and by individuals without a regular income because of their convenience and affordability [

35]. When socioeconomic levels increase, kiosks provide the main source of away-from-home foods [

36]. On the other hand, fast food establishments like Nando’s, Domino’s pizza, and Steers are mostly preferred by the working class in Uganda [

6].

The influence of EAFH on dietary intake and body weight differs according to the type of food establishment frequented, but we were unable to interrogate this topic due to limitations of the data used. It was reported in a 2014 review that, unlike restaurants, eating at fast-food restaurants greatly predicted an increase in body weight and waist circumference [

11]. Larson and others reported that frequent use of burger and French fry-restaurants was associated with a high risk of overweight and obesity, and excessive intake of energy, fat, and sugar-sweetened beverages, whereas frequent use of full-service restaurants was related to a higher vegetable intake [

37]. Studies are required to determine how socioeconomic status affects the choice of away-from-home food establishments, the contributions of different establishments to dietary and nutrient intake, and the influence of eating at different establishments on body weight in the Ugandan population.

This study has several limitations. First, respondents were asked to report the number of meals, including lunch, breakfast, and dinner, eaten per week that were not prepared at a home. Self-reported data has been frequently questioned in nutritional epidemiology because of its reliance on memory. For example, memory lapses could have resulted in over- or under-estimation of the number of meals consumed away from home in the present study. Nevertheless, we provide, for the first time, a broad view of the relationships between EAFH and overweight and obesity in the Ugandan population. Second, the cross-sectional nature of this study precludes the evaluation of causal relationships between EAFH and overweight and obesity. However, our study has some strengths. First, we used data obtained from a nationwide survey that included diverse tribal and socio-economic groups, and a wide age-range. Thus, the conclusions drawn can be generalized to the entire Ugandan population. Second, the study reveals sex and age-specific associations between EAFH and overweight and obesity that could be used to devise future interventions that target specific population sub-groups. Lastly, this study is the first in Uganda, and among a few in SSA, that investigated the relationships between EAFH and overweight and obesity in Uganda.

In conclusion, EAFH was positively associated with overweight and obesity, and these associations were modified by sex and age. A positive association was found between EAFH and overweight and obesity in men, and obesity in young/middle-aged adults, whereas a negative association was found between EAFH and overweight in women. Future studies should examine the influence of away-from-home food consumption at different establishments on body weight, their contribution to dietary intake, and the factors that influence the choice of eating at different establishments. Results from such studies would guide the design of systematic and effective interventions to modify the food environment and inform consumers about choosing healthy foods when dining out. In brief, our findings imply that nutritional interventions for obesity reduction in Uganda should target away-from-home eating, and that these interventions should specifically target men, young and middle-aged adults.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download