Abstract

Creation of guidelines and education on digital professionalism have been sluggish despite the ever-increasing use of social media by digitally native medical students, who are at risk of blurring the line between their professional and personal lives online. A qualitative thematic analysis was applied on 79 videos extracted from 70,154 YouTube videos uploaded by Korean medical students between March and April 2020. We found 20% contained at least one concerning behavior themed under ‘failure to engage,’ ‘disrespectful behaviors,’ or ‘poor self-awareness.’ Professional lapses identified were classified into seriousness levels. Mostly were “controversial’ or ‘concerning’ but some ‘highly concerning’ contents were also found. This is the first study on digital professionalism behavior on medical students' YouTube videos. The potential negative impact on the medical profession of the easily accessible public online videos cannot be ignored and thus we suggest the need for them to be taken more seriously.

Graphical Abstract

Medical professionalism is a set of fundamental concepts which demonstrates the relationship between doctors and society, thus behavioral guidelines have been proclaimed by medical authorities worldwide and added to the medical curriculum in undergraduate and postgraduate medical training.123 However, guidelines for digital professionalism and their integration to curricula are still under development despite medical students' and doctors' ever-increasing use of social media.4

Concepts of digital professionalism or e-professionalism have been defined as “attitudes and behaviors reflecting traditional professionalism paradigms but manifested through digital media,”5 or as “medical professionalism in physicians and students using digital media requires deliberate, ethical, and accountable usage, based on the principles of proficiency, reputation, and responsibility.”6 Medical students' professionalism lapses on digital media are increasingly being reported, examples include overlooking personal data protection, sharing patient identifiable information, using derogatory language, posting sexually suggestive contents, and blurring the boundaries between personal and professional lives.78910 Also, concerns have been raised on medical students' unawareness on the negative aspects or potential harm of social media on their lives.911

Previous studies on e-professionalism have focused on written/still image platforms such as Facebook10 but studies on video contents on platforms such as YouTube have been lacking (Supplementary Data 1). YouTube has become internet's largest video-sharing platform and the second-largest search engine after Google with over 2.3 billion users a month, and 81% of 18–25 year-olds are YouTube users,12 the typical medical student age range. A study on unprofessional behavior on social media by medical students reported 96.9% of their study participants (853 medical students) used YouTube.10 Medical students are creating explosive amounts of YouTube content for both learning and leisure purposes with great public accessibility and influence potential. Therefore, we need to educate medical students wisely on public video uploads while maintaining medical professionalism. A study exploring the current status of medical students' undesirable/unprofessional behaviors on YouTube would be a helpful start for education. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical research on digital professionalism on YouTube videos uploaded by medical students. The authors aimed to explore what types of unprofessional behaviors were present in YouTube videos posted by medical students (Supplementary Data 2).

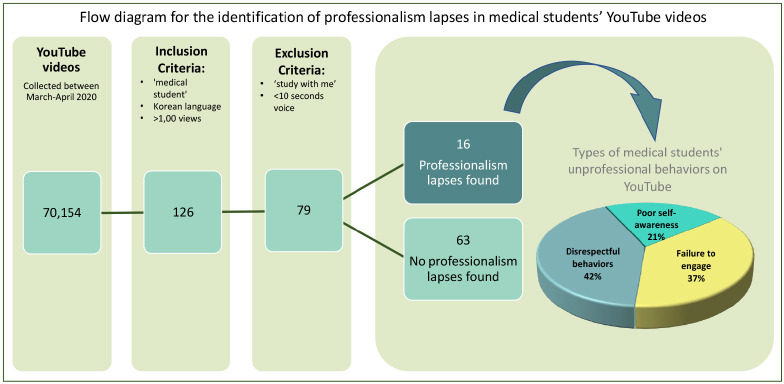

We purposefully collected YouTube videos uploaded by medical students between March 14th and April 25th, 2020. The selection criteria included: 1) search term ‘medical student’ in Korean; 2) Korean language; 3) > 1,000 views. Exclusion criteria included: 1) ‘study with me’ in titles or hashtags, implying studying without other actions; 2) < 10 seconds voice or subtitles. Basic statistics showing characteristics of analyzed videos were calculated: student year, sex, video type and content, and video length (Supplementary Table 1). Qualitative thematic analysis131415 using a deductive approach was conducted. A scheme for classifying medical students' unprofessional behaviors by van der Vossen et al.16 was applied as coding guide. Two co-authors analyzed and open coded the observed behaviors on YouTube videos independently, and all authors discussed and reconciled discrepancies, organizing a final code list where themes/sub-themes were generated through iterative discussions.

One-hundred and six videos were extracted after applying the inclusion criteria from the initial search of 70,154 YouTube videos. Seventy-nine videos remained after the exclusion criteria. Sixty-five percent of YouTubers were female and nearly half were preclinical year students (49.4%) followed by clinical (35.4%) and pre-medical (15.2%) year students. Videoblogs were the commonest type of recordings (68.4%) and the majority were personal life (44.3%) and daily student life (44.3%) in medical schools or teaching hospitals. Sixteen out of 79 videos (20.3%) showed at least one unprofessional behavior and seven videos demonstrated two or more elements of professionalism lapses.

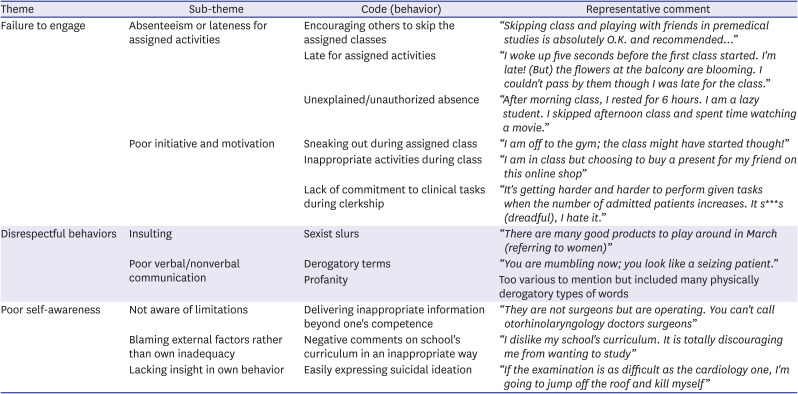

Identified unprofessional behaviors were classified into three themes: 1) failure to engage in academic tasks, 2) disrespectful behaviors, and 3) poor self-awareness (Table 1). Under ‘failure to engage in academic tasks,’, 2 sub-themes ‘absenteeism or lateness for assigned activities’ and ‘poor initiatives or motivation’ were identified and most were just ‘concerning.’ Specific behaviors in ‘absenteeism or lateness for assigned activities’ included encouraging others to skip assigned classes, being late for allocated activities, and unexplained or unauthorized absence. For example, a medical student encouraged fellow student truancy via YouTube video while another proudly showed themselves watching TV or going to the gym instead of attending class. Sneaking out during class, or recording inappropriate activities mid-class were included under ‘poor initiatives and motivation’. Some students failed to concentrate during class while bragging on YouTube about sleeping or online shopping mid-lectures. Lack of commitment to clinical tasks during clerkship was also included. A final year student negatively described their practical experiences at a hospital placement as: “It’s getting harder and harder to perform tasks when admitted patient number increases. It s***s (dreadful), I hate it.”

Behaviors included in the ‘disrespectful behavior’ theme varied from highly concerning to controversial in their seriousness levels. The highly concerning case included sexist slurs: “There are many good products to play around in March (referring to women).” Some behaviors under the ‘poor verbal/nonverbal communication’ sub-theme were definitely concerning professionalism lapses. Included were derogatory or mocking or insensitive language towards patients, peers, or physicians: “You are mumbling now; you look like a seizing patient.” However, profanity use was rated ‘controversial’ as it may fall under the freedom of self-expression if filmed outside of the school or hospital context, despite its potential negative public impact.

The ‘poor self-awareness’ theme included actions related to a lack of insight on the students' own's behavior or capacity, and the tendency to blame external factors rather than their own inadequacy. Negative comments concerning their own university or curriculum disregarded the potential reputational damage, and we categorized them under ‘controversial’ behaviors. We also included the commonly used but potentially serious suicidal language: “If the examination is as difficult as the cardiology one, I'm going to jump off the roof and kill myself” due to the undesirable behavior afront the public as future doctors.

Our study intended to explore the types of unprofessional behaviors on medical students’ YouTube videos. We found around 20% of collected videos contained at least one undesirable behavior classified under one of three categories: ‘failure to engage in academic tasks,’ ‘disrespectful behaviors,’ and ‘poor self-awareness.’ Each behavior under the theme ranged widely in the professional lapse's seriousness based on their potential negative impact at the individual or institutional level. Despite one highly concerning behavior of sexist slurs classified under ‘disrespectful behaviors,’ the majority of the coded behaviors were of lesser gravity. Encouraging absenteeism or lateness to assigned activities, and poor initiative and motivation in learning were clearly concerning behaviors. In contrast, undesirable behaviors such as usage of profanity or negative comments on their school's curriculum seem to fall under grey areas. Some people may insist them as part of individual freedom of speech, others may regard them as potential threat to the public trust on medical schools or tarnish university reputations. Profane language or biased criticism on medical schools on public online platforms may negatively impact the public's trust in the medical profession and fall below the standards expected of future doctors.17 Furthermore, when considering that YouTube videos are widely accessible to the public, their potential adverse effects cannot be ignored.

Current medical students are digital natives and very familiar with sharing information on social media but also vulnerable to blurring their professional and personal lives in the digital context. Kaczmarczyk et al.18 stated that digital professionalism includes the students' individual persona, reflecting professional identity, attitudes, and behaviors. Previous literatures on digital professionalism highlighted the importance of upholding reputation by behaving professionally and respectfully, and being responsible and aware of professional boundaries.619 Medical students may not be aware of social media's potential negative impact on their institutional reputation or professional identity. Therefore, medical schools should help students recognize the importance of distinguishing private and professional use of social media, and educate them how social media could potentially affect their standing as members of the medical profession. In addition, discussion on balancing freedom of speech within the limits of professionalism could be a good starting point for digital professionalism education.

This study has several limitations. Since we analyzed videos created by Korean medical students uploaded from March to April 2020, our results could just be the tip of the iceberg rather than being representative of Korean medical students. Nonetheless, we found a concerning number of professional lapses in our selected sample. We cautiously assume the existence of more concerning unprofessional behaviors on YouTube or other social media platforms to be commonplace if investigated in a larger scale. Even though our qualitative thematic analysis was conducted under scientific scrutiny, further triangulation could be considered to promote a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon observed in our study.

Our preliminary study findings would like to raise the issue of online professional lapses to be taken more seriously, considering the permanent and widely public nature of YouTube videos. We wish to suggest that digital professionalism in medical students should be rigorously investigated in a larger scale.

References

1. Hilton SR, Slotnick HB. Proto-professionalism: how professionalisation occurs across the continuum of medical education. Med Educ. 2005; 39(1):58–65. PMID: 15612901.

2. Kim DH. Social media guideline. Healthc Policy Forum. 2020; 18(1):38–42.

3. Kim CJ, Bhan YW. Maintaining professional dignity in the age of social media. Korean J Med Ethics. 2018; 21(4):316–329.

4. Sabin JE, Harland JC. Professional ethics for digital age psychiatry: boundaries, privacy, and communication. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017; 19(9):55. PMID: 28726059.

5. Cain J, Romanelli F. E-professionalism: a new paradigm for a digital age. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2009; 1(2):66–70.

6. Ellaway RH, Coral J, Topps D, Topps M. Exploring digital professionalism. Med Teach. 2015; 37(9):844–849. PMID: 26030375.

7. Guseh JS 2nd, Brendel RW, Brendel DH. Medical professionalism in the age of online social networking. J Med Ethics. 2009; 35(9):584–586. PMID: 19717700.

8. Chretien KC, Greysen SR, Chretien JP, Kind T. Online posting of unprofessional content by medical students. JAMA. 2009; 302(12):1309–1315. PMID: 19773566.

9. Osman A, Wardle A, Caesar R. Online professionalism and Facebook--falling through the generation gap. Med Teach. 2012; 34(8):e549–e556. PMID: 22494078.

10. Barlow CJ, Morrison S, Stephens HO, Jenkins E, Bailey MJ, Pilcher D. Unprofessional behaviour on social media by medical students. Med J Aust. 2015; 203(11):439. PMID: 26654611.

11. Thompson LA, Dawson K, Ferdig R, Black EW, Boyer J, Coutts J, et al. The intersection of online social networking with medical professionalism. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(7):954–957. PMID: 18612723.

12. GMI Blogger. YouTube User Statistics 2021. [place unknown]: Infographics, Social Media Marketing;2021.

13. Barbour RS. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ. 2001; 322(7294):1115–1117. PMID: 11337448.

14. Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001; 358(9280):483–488. PMID: 11513933.

15. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000; 320(7227):114–116. PMID: 10625273.

16. Mak-Van Der Vossen M, Van Mook W, Van Der Burgt S, Kors J, Ket JCF, Croiset G, et al. Descriptors for unprofessional behaviours of medical students: a systematic review and categorisation. BMC Med Educ. 2017; 17(1):164. PMID: 28915870.

17. General Medical Council. Good Medical Practice: Working with Doctors, Working with Patients. London, UK: General Medical Council;2013.

18. Kaczmarczyk JM, Chuang A, Dugoff L, Abbott JF, Cullimore AJ, Dalrymple J, et al. e-Professionalism: a new frontier in medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2013; 25(2):165–170. PMID: 23530680.

19. Bahr TJ, Crampton NH, Domb S. The facets of digital health professionalism: defining a framework for discourse and change. Shachak A, Borycki EM, Reis SP, editors. Health Professionals' Education in the Age of Clinical Information Systems, Mobile Computing and Social Networks. London, UK: Elsevier/Academic Press;2017. p. 65–89.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary Table 1

Characteristics of the analyzed videos on YouTube (n = 79)

Table 1

Medical students' unprofessional behaviors on YouTube videos

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download