1. Hall JE, Hall ME. 28. Renal tubular reabsorption and secretion. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. 14th ed. St. Louis (MO): Elsevier Health Sciences;2020. p. 343–360.

2. Heaney RP. Role of dietary sodium in osteoporosis. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006; 25(Suppl):271S–276S. PMID:

16772639.

3. Anderson CA, Appel LJ, Okuda N, Brown IJ, Chan Q, Zhao L, Ueshima H, Kesteloot H, Miura K, Curb JD, Yoshita K, Elliott P, Yamamoto ME, Stamler J. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: the INTERMAP study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010; 110:736–745. PMID:

20430135.

4. World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease. Geneva: World Health Organization;2004.

6. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Health Statistics 2017: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VII-2). Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017.

7. Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2009; 339(nov24 1):b4567. PMID:

19934192.

8. Haddy FJ. Role of dietary salt in hypertension. Life Sci. 2006; 79:1585–1592. PMID:

16828490.

9. Tsugane S. Salt, salted food intake, and risk of gastric cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Sci. 2005; 96:1–6. PMID:

15649247.

10. Itoh R, Suyama Y, Oguma Y, Yokota F. Dietary sodium, an independent determinant for urinary deoxypyridinoline in elderly women. A cross-sectional study on the effect of dietary factors on deoxypyridinoline excretion in 24-h urine specimens from 763 free-living healthy Japanese. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999; 53:886–890. PMID:

10557002.

11. Folsom AR, Parker ED, Harnack LJ. Degree of concordance with DASH diet guidelines and incidence of hypertension and fatal cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens. 2007; 20:225–232. PMID:

17324731.

12. World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization;2003.

13. Ministry of Health and Welfare. The Korean Nutrition Society. Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans 2015. Seoul: The Korean Nutrition Society;2015.

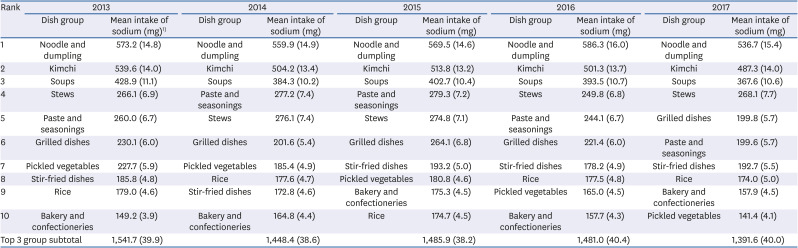

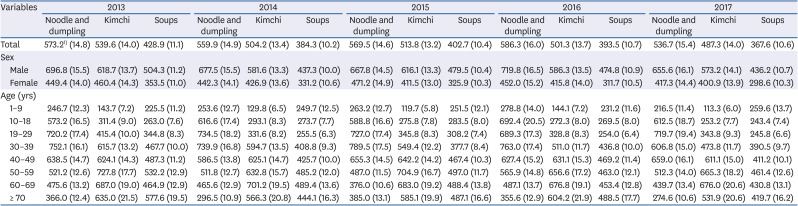

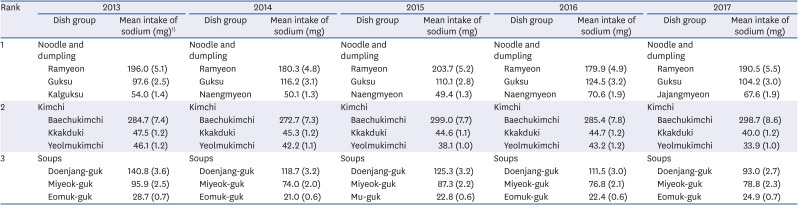

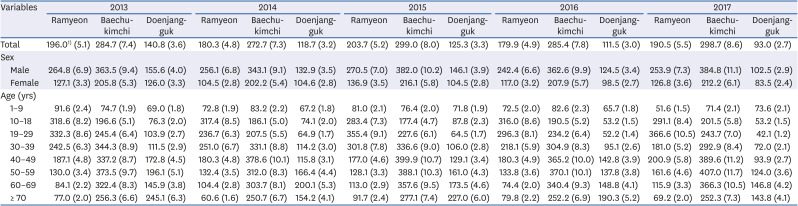

14. Yon M, Lee Y, Kim D, Lee J, Koh E, Nam E, Shin H, Kang BW, Kim JW, Heo S, Cho HY, Kim CI. Major sources of sodium intake of the Korean population at prepared dish level -based on the KNHANES 2008 & 2009-. Korean J Community Nutr. 2011; 16:473–487.

15. Song DY, Park JE, Shim JE, Lee JE. Trends in the major dish groups and food groups contributing to sodium intake in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1998-2010. Korean J Nutr. 2013; 46:72–85.

16. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, Chun C, Khang YH, Oh K. Data resource profile: the Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43:69–77. PMID:

24585853.

17. Kim SY, Kang MS, Kim SN, Kim JB, Cho YS, Park HJ, Kim JH. Food composition tables and national information network for food nutrition in Korea. Food Sci Ind. 2011; 44:2–20.

18. Jackson SL, King SM, Zhao L, Cogswell ME. Prevalence of excess sodium intake in the United States—NHANES, 2009–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016; 64:1393–1397. PMID:

26741238.

19. Saito A, Imai S, Htun NC, Okada E, Yoshita K, Yoshiike N, Takimoto H. The trends in total energy, macronutrients and sodium intake among Japanese: findings from the 1995–2016 National Health and Nutrition Survey. Br J Nutr. 2018; 120:424–434. PMID:

29860946.

20. Park YS, Son SM, Lim WJ, Kim SB, Chung YS. Comparison of dietary behaviors related to sodium intake by gender and age. Korean J Community Nutr. 2008; 13:1–12.

21. Kim HY. Activation of nutrition labeling in food and restaurant industry for sodium reduction. Food Sci Ind. 2011; 44:28–38.

22. Kim MG, Kim KY, Nam HM, Hong NS, Lee YM. The relationship between lifestyle and sodium intake in Korean middle-aged workers. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc. 2014; 15:2923–2929.

23. Shin EK, Lee HJ, Jun SY, Park EJ, Jung YY, Ahn MY, Lee YK. Development and evaluation of nutrition education program for sodium reduction in foodservice operations. Korean J Community Nutr. 2008; 13:216–227.

24. Lee KW, Lee HS, Lee MJ. A study on the eating behaviors of self-purchasing snack among elementary school students. Korean J Food Cult. 2005; 20:594–602.

25. Gibson J, Armstrong G, McIlveen H. A case for reducing salt in processed foods. Nutr Food Sci. 2000; 30:167–173.

26. Yoon MO, Lee HS, Kim K, Shim JE, Hwang JY. Development of processed food database using Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. J Nutr Health. 2017; 50:504–518.

27. Park YH, Chung SJ. A comparison of sources of sodium and potassium intake by gender, age and regions in Koreans: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2010–2012. Korean J Community Nutr. 2016; 21:558–573.

28. Yon M, Lee MS, Oh SI, Park SC, Kwak CS. Assessment of food consumption, dietary diversity and dietary pattern during the summer in middle aged adults and older adults living in Gugoksoondam logevity area, Korea. Korean J Community Nutr. 2010; 15:536–549.

29. Kim CH, Han JS. Hypertension and sodium intake. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2006; 27:517–522.

30. Lee GY, Han JA. Demand for elderly food development: relation to oral and overall health focused on the elderly who are using senior welfare centers in Seoul. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2015; 44:370–378.

31. Son SM, Park YS, Lim HJ, Kim SB, Jeong YS. Sodium intakes of Korean adults with 24-hour urine analysis and dish frequency questionnaire and comparison of sodium intakes according to the regional area and dish group. Korean J Community Nutr. 2007; 12:545–558.

32. Oh HI, Choi EK, Jeon EY, Cho MS, Oh JE. An exploratory research for reduction of sodium of Korean HMR product-analysis on labeling of Guk, Tang, Jjigae HMR products in Korea-. J Korea Contents Assoc. 2019; 19:510–519.

33. Lee JS, Kim J, Hong KH, Jang YA, Park SH, Sohn YA, Chung HR. A comparison of food and nutrient intakes between instant noodle consumers and non-consumers among Korean children and adolescents. Korean J Nutr. 2009; 42:723–731.

34. Chang SO. The amount of sodium in the processed foods, the use of sodium information on the nutrition label and the acceptance of sodium reduced ramen in the female college students. Korean J Nutr. 2006; 39:585–591.

35. Kim SH, Jeong YJ. Domestic and international trends in sodium reduction and practices. Food Sci Ind. 2016; 49:25–33.

36. Lee SY, Lee SY, Ko YE, Ly SY. Potassium intake of Korean adults: based on 2007~2010 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Nutr Health. 2017; 50:98–110.

37. Salvador Castell G, Serra-Majem L, Ribas-Barba L. What and how much do we eat? 24-hour dietary recall method. Nutr Hosp. 2015; 31(Suppl 3):46–48. PMID:

25719770.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download