INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of asthma has increased worldwide, and it is a serious global health problem as well as in Korea.

1 Uncontrolled asthma decreases the quality of life and functioning of patients, and causes a considerable economic burden.

12 International and national asthma management guidelines were first established in the late 1980s and early 1990s,

3 and Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guideline and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) guidelines for asthma have since been updated and revised. The Korean asthma management guidelines were first published in 1994 and have since been updated and revised. The latest version was published in 2015.

4

Physician compliance with asthma management guidelines can improve the clinical course of asthma,

5 and guideline-based asthma symptom control is associated with reduced medical costs.

6 However, the Asthma Insights and Reality in Asia-Pacific study showed that asthma was poorly controlled in a high proportion of patients and the frequency of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) use was very low (13.6%).

7 The low prescription rate was not confined to Asia; the figures were 14.6% in the United States (in 1998),

8 43% in Europe (1999–2002),

9 and 38.4% in Germany (2008–2011).

10 This suggests a gap between the recommendations of asthma management guidelines and actual clinical practice. Several studies have evaluated physician awareness of asthma guidelines and the barriers to their use.

11121314 The self-reported awareness rates are 88%–91%

1213 but the compliance rates are 39%–53% for various guideline components.

13 The reasons for non-compliance with asthma guidelines include internal barriers (lack of awareness, lack of familiarity, disagreement with the guidelines, and concerns about effectiveness) and external barriers (patient, environmental, and guideline factors).

1314 In Korea, assessment of the adequacy of asthma management has been undertaken by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA), and the rates of pulmonary function test performance and ICS prescription are continuously reported. We evaluated the implementation of asthma management guidelines before the asthma adequacy assessment, and so it is meaningful to identify the changes after implementation of the policy. Also, no study of the obstacles and alternatives to implementation of the guidelines reported by clinical physicians in Korea has been performed. Therefore, by identifying the obstacles cited by Korean physicians, we hope to establish a basis for improving asthma care. This study is the first investigation of the implementation of the asthma management guidelines among physicians, the barriers to their implementation, and alternatives to the guidelines reported by physicians in Korea.

DISCUSSION

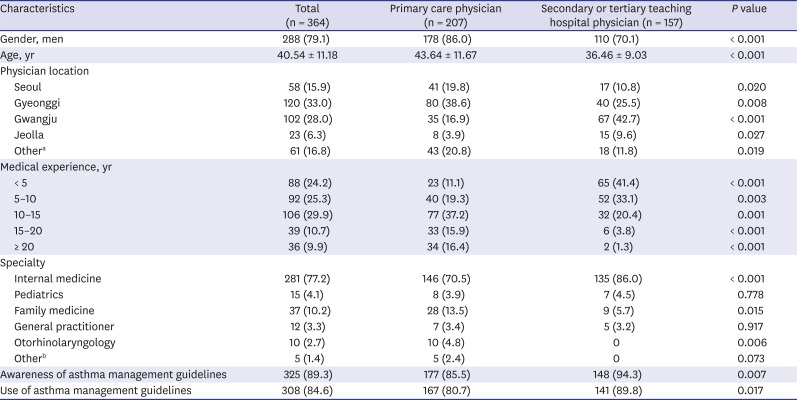

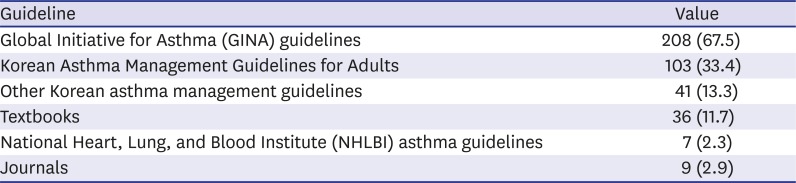

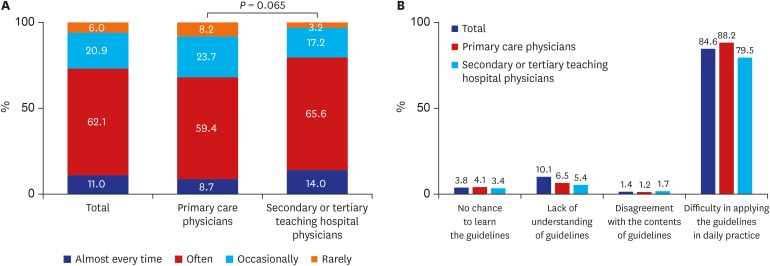

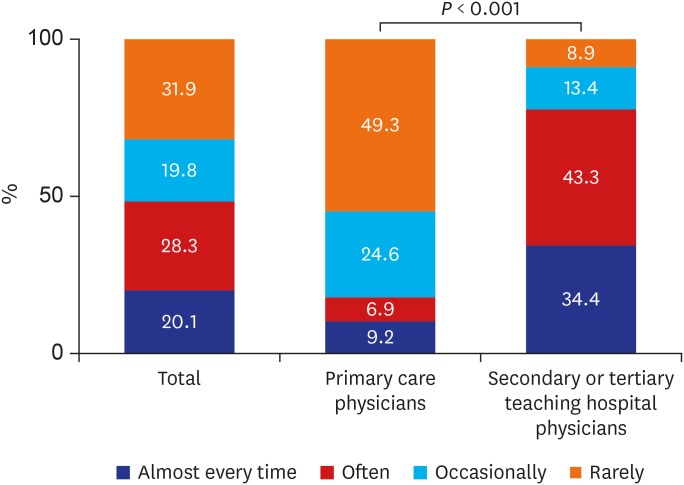

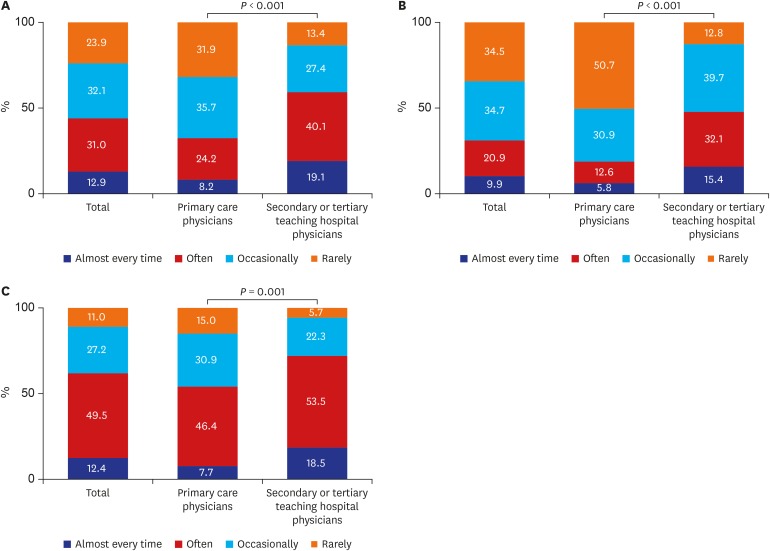

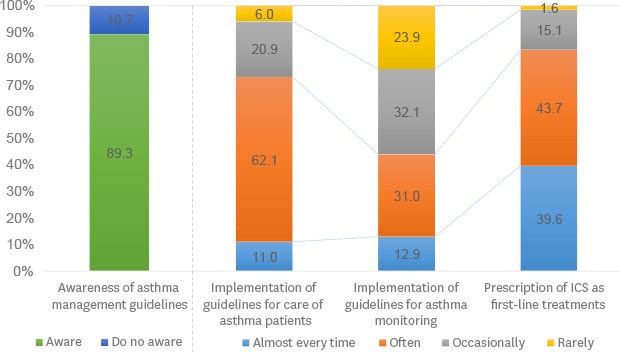

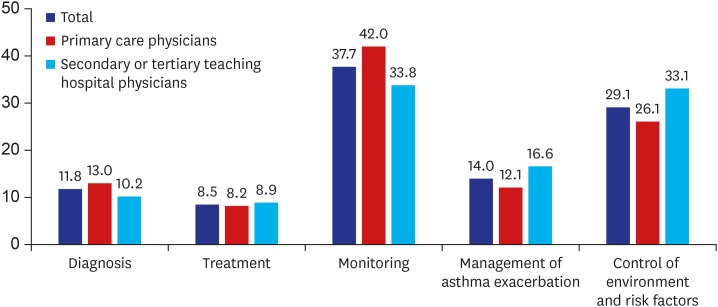

We report here that the rate of compliance with the asthma management guidelines is low in current practice despite a high level of awareness among physicians in Korea. About 90% of physicians stated that they knew the asthma guidelines, and 85% reported that they were using them. However, the questionnaires exploring diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment revealed low compliance rates; the rates of performing pulmonary function tests for diagnosis and monitoring were 20.1% and 9.9%, respectively, and the rate of ICS prescription was 39.6%. The reasons for non-compliance with the asthma management guidelines included difficulty in applying them in daily practice. The questionnaire did not inquire about difficulties in applying the guidelines, but this can be estimated based on the responses to the difficulties in implementing them. Physicians stated that ‘asthma monitoring’ was the most difficult aspect of asthma care. Asthma monitoring includes identifying the level of asthma symptom control (daytime symptoms, nighttime symptoms, reliever use, and activity limitation) and risk factors for poor asthma outcomes (e.g., ICS use, comorbidities, risk factor exposure, and low lung function).

15 Therefore, lung function should be periodically measured because it is an objective indicator of the future risk of asthma exacerbation. However, the physicians reported a low rate of performance of pulmonary function tests for diagnosis and monitoring. Lack of pulmonary function measurement has been reported in other studies; daily peak flow meters were used by 30%–38% of physicians

1316 and spirometry was used by 20.6% for diagnosis and 8.3% for monitoring asthma.

12 This study was performed several years ago, and so the results may not be representative of the current status. However, we can evaluate the current status using the assessment of asthma management adequacy by HIRA. This adequacy assessment aims to encourage clinicians to perform pulmonary function tests and prescribe ICS appropriately for asthma patients. The first assessment of asthma management adequacy was conducted from July 2013 to June 2014. Among the 16,804 medical institutions, 87.75% were clinics, and the rate of performance of pulmonary function tests was 23.47% and 17.06%, respectively.

17 The results of the most recent (fifth) asthma adequacy assessment from July 2017 to June 2018 (16,924 organizations [46.7%]; 14,942 clinics [88.3%]) were announced in April 2019. The pulmonary function test rate was 33.1% (tertiary hospitals 87.4%, general hospitals 72.3%, and clinics 23.1%).

18 The rate of performance of pulmonary function tests increased over time and was higher than the performance rate in this study (conducted before the adequacy evaluation). This improvement might be attributable to emphasizing the need for pulmonary function tests by conducting assessments of asthma management adequacy and including such tests in quality assessments. Therefore, our study is meaningful as it provides comparative data on the status before asthma adequacy assessment and indicates that promotion of pulmonary function testing can be helpful. Nevertheless, the consistently low rate of performance of pulmonary function tests in primary care hospitals suggests that there are a number of obstacles. The barriers associated with lung function measurement were described by Cabana et al.

14 and include concerns about effectiveness, lack of physician training, no time for appropriate measurement, lack of educational resources, patient non-compliance, and patient inability to obtain spacers not covered by insurance. The persistently low rate after implementation of a policy of promoting pulmonary function testing suggests that environmental factors are more important than physician factors; the former include a lack of pulmonary function test facilities or a lack of physician and staff training.

Physicians stated that it was difficult to control environmental and risk factors. We did not identify the reasons for the difficulty of environmental control, but these reportedly include a lack of confidence in its effectiveness or the indications for control, a lack of time, or competence in terms of appropriate counseling, and patient non-compliance (such as refusal to part with a family pet).

14 Therefore, it is necessary to emphasize that exposure to risk factors for allergic diseases can result in the aggravation of allergic symptoms,

19 which requires an in-depth understanding of asthma management guidelines. Physicians prefer to use immediately available information (such as algorithms and flow sheets) for rapid decision-making in clinical settings.

2021 Cho et al.

22 reported significantly improved clinical outcomes and increased physician compliance with guidelines after the development of a practical and simple, computerized asthma management program, ‘Easy Asthma Management.’ Therefore, there is a need for a content delivery method that can be easily used by physicians, such as handouts or simple videos. Furthermore, this would enable patients to be educated about how to modulate their environment to promote asthma control by allowing physicians to deliver sufficient information in a limited period of time.

Both international and national asthma management guidelines recommend ICSs as the first-line treatment for most patients with persistent asthma symptoms.

423 A systematic review of Korean practices from 1990 to 2004 found that ICSs were prescribed for 16% of patients with mild asthma and 21% of those with severe asthma.

24 The ICS prescription rate for Korean asthma patients (based on the HIRA database from July 2013 to June 2014) was 22.6% (20.7% of patients visiting primary healthcare clinics vs. 84.2% of those visiting tertiary teaching hospitals).

25 In addition, assessment of asthma management adequacy showed an improvement in current prescriptions for ICS. The percentage of patients with an ICS prescription in the fifth assessment was 36.6% (tertiary hospitals 89.9%, general hospitals 75.3%, and clinics 24.3%).

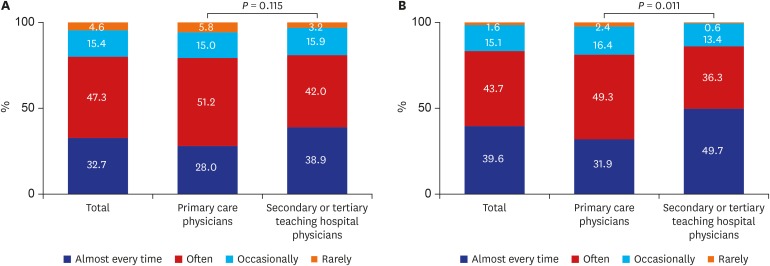

18 In our study, primary care physicians exhibited the highest rate of ICS use (39.6% of all physicians, 31.9% of primary care physicians, and 49.7% of secondary or tertiary teaching hospital physicians). This may be attributable to differences in the subjects; the physicians enrolled in this study were attending an educational course that included asthma management, and thus wished to engage in continuing education. In contrast, the oral corticosteroid (OCS) prescription rate in the fifth assessment of asthma management adequacy was 26.5% in all hospitals and 32.6% in primary care hospitals.

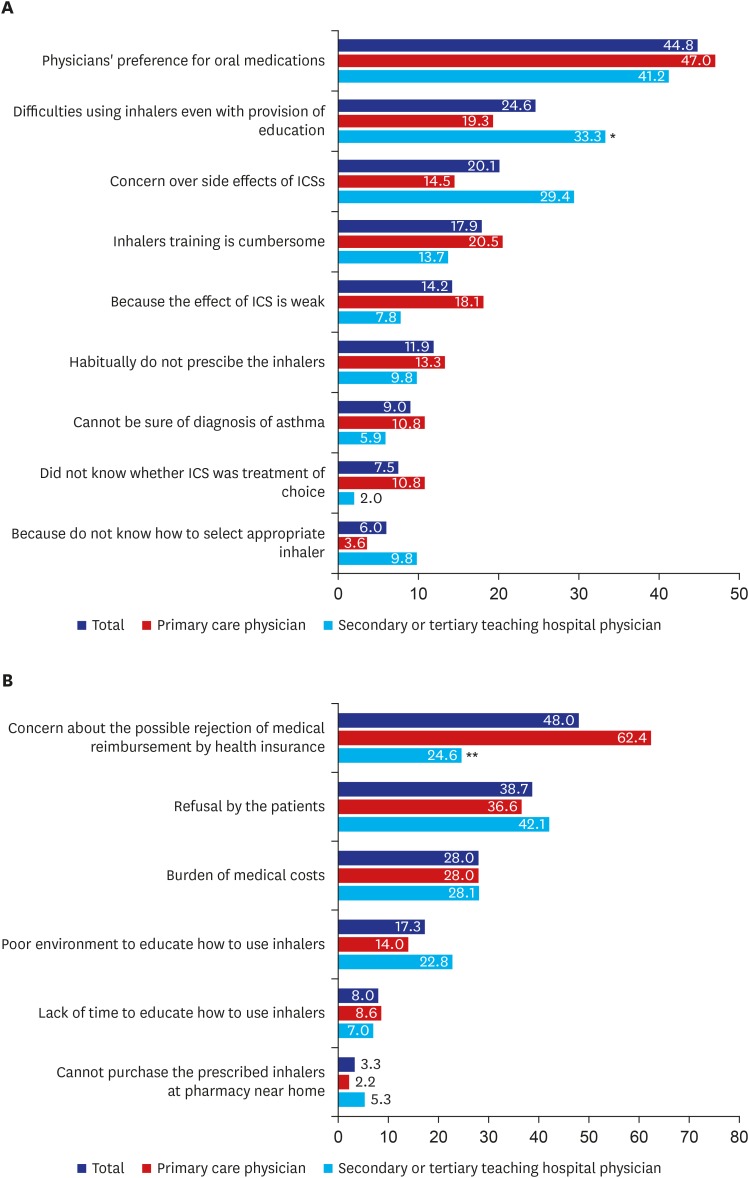

18 The low ICS prescription rate and the cause of the high OCS prescription rate in Korea need to be evaluated. The reason for the high rate of OCS prescription can be estimated from the responses in this study. The obstacles to ICS prescription were divided into internal and external factors. The major internal barrier was physician preference for oral medications, and the major external barrier was refusal by the patient to use an inhaler. This suggests a lack of physician and patient awareness of inhalants. ICSs can achieve a sufficient therapeutic effect at low doses and have fewer side effects because their systemic absorption is negligible. However, even the secondary and tertiary training hospital physicians, who had relatively high rates of ICS prescription, were reluctant to prescribe inhalants. They stated that this is due to difficulty in their use even with appropriate education and concerns over side effects. However, repeated inhaler training reportedly improves the proficiency of inhaler use.

2627 Furthermore, primary care physicians stated that inhaler training was cumbersome and the environment to educate how to use inhalers was poor.

Another important barrier was concern about the rejection of medical reimbursement by health insurance, particularly by the primary care physicians. Currently, ICSs for the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases (KCD) code for asthma are covered by health insurance. However, inhalers containing an ICS and a long-acting beta agonist are covered by health insurance only for patients with ‘partly or uncontrolled asthma’ (KCD code JX999). If ‘partly or uncontrolled asthma’ is not described or is omitted, the medical reimbursement request will be rejected by health insurance, resulting in prescription of oral anti-asthma agents instead.

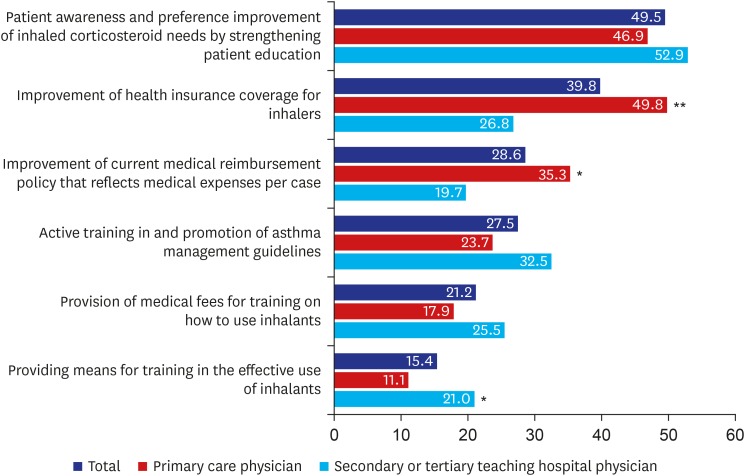

In summary, the low inhaler prescription rate was due to physician and patient preferences for oral agents as well as environmental factors such as rejection of medical reimbursement by health insurance and the difficulty performing pulmonary function tests and inhaler training. Therefore, it is necessary to improve awareness of the therapeutic efficacy and fewer side effects of ICS for the treatment of asthma by means of education programs or policy. However, the alternatives proposed by the physicians suggest that a promotion policy of prescribing ICS has limitations. The primary care physicians, who lacked the ability to implement the guidelines, stated that improvement of insurance coverage for inhalers was most important, and the secondary or tertiary hospital physicians stated that improvement of environmental factors, such as provision of appropriate rewards (e.g., reimbursement of the cost of patient education) and the effective means for inhaler training, was the most important.

This study had several limitations. First, only physicians attending an educational course were enrolled; thus, the population was highly selective clinicians and not representative of all physicians in Korea. Additionally, there might be a difference between the physicians' answers and their actual habits because they were required to estimate how often they applied asthma management guidelines. There was also the possibility that physicians might have different criteria for performing routine pulmonary function tests for diagnosis or monitoring. Finally, because this survey included training hospitals, many of the physicians at secondary and tertiary hospitals had less than 10 years of experience, which might have affected the results.

We report here a considerable gap between asthma management guidelines and real practice and barriers to their implementation. Those barriers in Korea are somewhat different to those in other countries, such as physician attitudes (e.g., disagreement with guidelines, lack of confidence, lack of expectation of good outcomes, and a lack of interest in changing previous practices), guideline related barriers (e.g., difficulty in application, inconvenience, and lack of clarity), patient-related barriers (e.g., inability to reconcile patients' preferences with the recommendations), and environmental factors (e.g., lack of a reminder system, lack of counseling materials, insufficient staff or consultant support, poor reimbursement, increased practice costs, and increased liability).

28 Therefore, to implement asthma management guidelines in Korea, it is important to improve medical reimbursement policies and the level of awareness of such guidelines.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download