Abstract

Objectives

This study examined whether the infant feeding type and duration are related to the introduction of complementary feeding, and whether the appropriate introduction of complementary feeding in infancy is related to tooth decay in toddlers.

Methods

The subjects were 1,521 toddlers among 2~3 year old children in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 2008 to 2015. The toddlers were divided into the appropriate group (4~6 months) and delayed group (>6 months) according to the timing of complementary feeding introduction.

Results

The delayed group were 26.5% of subjects and the formula feeding period in the appropriate group and delayed group was 8.4 and 10.3 months, respectively (P=0.002). On the other hand, there was no difference in the breastfeeding period between the appropriate group and delayed group (P=0.6955). Early childhood caries was more common in the delayed group (P=0.0065). The delayed introduction of complementary feeding was associated with a risk of early childhood caries according to the logistic models (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.27–2.57).

Conclusions

The introduction of complementary feeding is associated with early childhood caries. Therefore, the importance of the proper introduction of complementary feeding in infancy should be emphasized, and public relations and education for maternal care and breastfeeding should be provided through health care institutions.

Figures and Tables

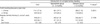

Table 2

Comparison of dental care behavior according to the complementary feeding introduction N (%)

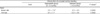

Table 4

Comparison of feeding duration according to the complementary feeding introduction (Mean ± SD)

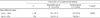

Table 5

Distribution of participants introduction of complementary feeding and early childhood caries N (%)

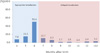

Table 7

Odds ratio for early childhood caries among 2~3 years old toddlers (N=1,390)

Data were analyzed by complex samples logistic regression.

Independent variable is introduction of complementary feeding (categorical variable).

Model 1: Models were unadjusted association.

Model 2: Models were adjusted for household income and mode of feeding

Model 3: Models were adjusted for household income, mode of feeding and regular dental checkup

Model 4: Models were adjusted for household income, mode of feeding and tooth brushing frequency

Model 5: Models were adjusted for household income, mode of feeding, regular dental checkup, and tooth brushing frequency

Bold denotes p<0.05.

References

1. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Clinical Affairs Committee. Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): classifications, consequences, and preventive strategies. Pediatr Dent. 2008; 30(7):40–43.

3. Pitts N, Harker R. Obvious decay experience children's dental health in the United Kingdom 2003. London: Office for National Statistics;2004.

4. Filstrup SL, Briskie D, da Fonseca M, Lawrence L, Wandera A, Inglehart MR. Early childhood caries and quality of life: child and parent perspectives. Pediatr Dent. 2003; 25(5):431–440.

5. Low W, Tan S, Schwartz S. The effect of severe caries on the quality of life in young children. Pediatr Dent. 1999; 21(6):325–326.

6. Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2015 Korean children's oral health survey. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2015.

7. Davies GN. Early childhood caries-a synopsis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998; 26(S1):106–116.

8. Berkowitz RJ. Causes, treatment and prevention of early childhood caries: a microbiologic perspective. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003; 69(5):304–307.

9. Feldens CA, Giugliani ER, Vigo A, Vitolo MR. Early feeding practices and severe early childhood caries in four-year-old children from southern Brazil: a birth cohort study. Caries Res. 2010; 44(5):445–452.

10. Chaffee BW, Feldens CA, Rodrigues PH, Vitolo MR. Feeding practices in infancy associated with caries incidence in early childhood. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015; 43(4):338–348.

11. Chaffee BW, Feldens CA, Vitolo MR. Association of long-duration breastfeeding and dental caries estimated with marginal structural models. Ann Epidemiol. 2014; 24(6):448–454.

12. Chaudhary SD, Chaudhary M, Singh A, Kunte S. An assessment of the cariogenicity of commonly used infant milk formulae using microbiological and biochemical methods. Int J Dent. 2011; 2011:320798.

13. Tham R, Bowatte G, Dharmage SC, Tan DJ, Lau MX, Dai X. Breastfeeding and the risk of dental caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015; 104(467):62–84.

14. Park DH, Lee KH, Kim DE. In vitro study of cariogenic potential of infant formulas. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 2000; 27(1):32–39.

15. Heo YW, Kim SJ, Lee KH. In vitro study of baby food and breakfast cereal as for buffering capacity, acid production by Streptococcus Mutans, and synthetic hydroxyapatitie decalcification. J WonKwang Dent Res Inst. 1990; 1(1):167–176.

16. Korea Consumer Agency. Issues and measures for baby foods. Chungbuk: Korea Consumer Agency;2000.

17. Consumers Union of Korea. Analysis of sugar and sodium contents for baby food. Seoul: Consumers Union of Korea;2015.

18. World Health Organization. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. Washington, D. C.: World Health Organization;2010.

19. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. A survey on breast-feeding in Korea. Sejong: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2016.

20. Park YH, Lee SS, Jung LH. Perception and use of weaning diets by housewives in Gwangju-Jeonnam regions. Korean J Food Cook Sci. 2006; 22(6):799–807.

21. Kim SO. Study on the direction for development of instant weaning food through purchase survey of feeding habit [Master's thesis]. Chung-Ang University;2012.

22. Agostoni C, Decsi T, Fewtrell M, Goulet O, Kolacek S, Koletzko B. Complementary feeding: a commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008; 46(1):99–110.

23. World Health Organization. Complementary feeding of young children in developing countries: a review of current scientific knowledge. Geneva: World Health Organization;1998.

24. Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, Franca GV, Horton S, Krasevec J. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016; 387(10017):475–490.

25. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. The 2012 national survey on fertility, family health and welfare in Korea. Sejong: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2010.

26. Lee JH. A study on mothers' perceptions of weaning diets and the use of commercial weaning foods in Ulsan [Master thesis]. Ulsan University;2016.

27. American Dental Association. For the dental patient. Tooth eruption: The primary teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005; 136(11):1619.

28. Yom HW, Seo JW, Park HP, Choi KH, Chang JY, Ryoo E. Current feeding practices and maternal nutritional knowledge on complementary feeding in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2009; 52(10):1090–1102.

29. Lee CH, Jeong TS, Kim S. A pilot survey of the state of feeding, oral hygiene care tooth eruption and caries in 18-month old infants. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 2004; 31(4):714–720.

30. Ventura AK, Worobey J. Early influences on the development of food preferences. Curr Biol. 2013; 23(9):R401–R408.

31. Beauchamp GK, Moran M. Acceptance of sweet and salty tastes in 2-year-old children. Appetite. 1984; 5(4):291–305.

32. Wendt LK, Hallonsten AL, Koch G, Birkhed D. Analysis of caries-related factors in infants and toddlers living in Sweden. Acta Odontol Scand. 1996; 54(2):131–137.

33. Wan AK, Seow WK, Purdie DM, Bird PS, Walsh LJ, Tudehope DI. A longitudinal study of Streptococcus mutans colonization in infants after tooth eruption. J Dent Res. 2003; 82(7):504–508.

34. Zhao W, Li W, Lin J, Chen Z, Yu D. Effect of sucrose concentration on sucrose-dependent adhesion and glucosyltransferase expression of S. mutans in children with severe early-childhood caries (S-ECC). Nutrients. 2014; 6(9):3572–3586.

35. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, anticipatory guidance/counseling, and oral treatment for infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2013; 35(5):E148–E156.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download