Abstract

Background

Tauopathies are a group of diseases caused by the accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau protein in the central nervous system. Previous studies have revealed that there is considerable overlap in clinical, pathological, and genetic features among different taupathies.

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is the second most common early onset neurodegenerative disorder with an average age of onset of 50-60 years. It is clinically characterized by progressive behavioral changes and frontal executive deficits and/or selective language difficulties.1 As a neuropathologically heterogeneous disorder, it encompasses a range of different clinical syndromes, including the behavioral variant of FTD, the language variants, the semantic variant primary progressive aphasia, and nonfluent/agrammatic primary progressive aphasia (nfvPPA).12 The nfvPPA is clinically characterized by profoundly slowed and effortful non-fluent speech resulting from several different pathologies.3 Previous studies have reported that nfvPPA associated with taupathy has overlapping clinical features such as corticobasal degeneration (CBD) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) that may represent different points of a single disease spectrum.4567 To the best of our knowledge, there are only a few case reports on tau spectrum disorder including nfvPPA, CBD, and PSP that have described detailed changes of the clinical and laboratory changes based on longitudinal follow-ups. Herein, we report a patient with clinical course of nfvPPA, CBD, and PSP with initial clinical presentation of a progressive speech disorder.

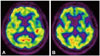

A 72-year-old man presented to neurocognitive behavior center of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital in 2009 with a three-year history of progressive speech disorder. In 2006, he was a pastor of a church with initial symptom of intermittent speech disorder while preaching. It was prominent especially when he got agitated. The intermittent symptom progressed to slow speech in 2007. Therefore, he visited other neurological clinics. Initial brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and neuropsychological test demonstrated no significant abnormal findings. The initial impression was speech disorder due to psychic stress. In 2009, his symptoms were aggravated. He was referred to our dementia center. His speech was non-fluent, monotonous, and slow with word-finding difficulties and intermittent paraphasia. He had a hard time with initiation of speech with relatively spared comprehension that suggested an initial stage of non-fluent type of primary progressive aphasia. His basic neurological examination was normal. There was no definite problem in other cognitive functions, daily activity, or emotion. The patient was right-handed. He graduated from a graduate school. His past medical history and familiar history were unremarkable. He had had a thyroid operation thirty years before. He never smoked nor drank. At an initial work up in 2007, routine laboratory evaluation and brain MRI were normal. The Korean version of the mini-mental state examination (K-MMSE) revealed a score of 28/30 in another neurologic clinic. In 2009, the patient scored 23/30 on the K-MMSE. Therefore, comprehensive neuropsychological test (Table 1) was performed. He got lower scores, especially on frontal executive function. Scores on stroop test color reading, semantic word fluency, and phonemic word fluency all fell below normal limits. His digit span, immediate recall, and delayed recall all declined. In language function, naming score also declined with non-fluent spontaneous speech. Because of this predominant language dysfunction, he was evaluated for the Korean version of Western Aphasia Battery. His fluency score was 18/20 points (91 percentile). He spoke without definite grammatical error. However, it was slow, effortful, and disrupted by intermittent phonemic paraphasia. His comprehension score was 9.5/10 points (94 percentile), which was relatively better than fluency test. His repetition score was decreased to 9.4/10 points (81 percentile). He had difficulty in repeating sentences with more than three phrases. His naming score and Aphasia quotient score were 8.8/10 points (89 percentile) and 91.4 (91 percentile), respectively. He was not clearly categorized into any sub types of aphasia based on taxonomy8 at that point. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomopraphy (FDG-PET) imaging demonstrated hypometabolism in the left posterior frontal and temporal cortex as well as left basal ganglia (Fig. 1A).

In 2010, his symptom progressed up to the degree with much slower and non-fluent speech as well as prominent dysphasia and grammatical errors, whereas his comprehension was relatively preserved. Besides those non-fluent aphasia symptoms, he also started to complain about progressive right hand clumsiness. Subsequent neurologic examination showed rigidity, mild bradykinesia at bilateral arms more predominantly on the right side without other parkinsonism such as gait disturbance, resting tremor or postural instability, and motor symptoms that were not improved at a daily dose of carbidopa-levodopa 50 mg and 500 mg for more than one year of medication. Brief cognitive test revealed abnormality in fist-edge-palm test and alternating hand movement test as well as ideomotor apraxia. At this stage, the possibility of CBD was raised based on cortical and asymmetric extrapyramidal dysfunction. On neuropsychological test, his frontal executive function became more declined on semantic, phonemic word fluency, stroop test color, and word reading tests. His ideomotor praxis was abnormal. His score on Rey complex figure test was significantly decreased (Table 1).

In 2011, he encountered postural instability with frequent falling as well as much progressed aphasia with clumsiness of the right hand. On neurological examination, his upward and downward vertical saccades were impaired with intact oculocephalic reflex implicating PSP.

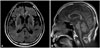

In 2012, non-fluent aphasia became more pronounced that his speech was very slow and effortful, consisting of just one or two words sentences with impaired repetition, naming, reading, and writing. However, his comprehension was still relatively intact for words and simple sentences. Neurological examination revealed more prominent vertical gaze limitation, horizontal hypometric saccadic, and smooth pursuit movement. Motor symptoms became more prominent with asymmetric bilateral limb rigidity, axial rigidity, severe bradykinesia, and severe gait abnormality such as short-stepped and festinating gait with frequent falls. Brain MRI revealed diffuse cerebral atrophy with equivocal midbrain atrophy (Fig. 2). Follow-up images of FDG-PET scan revealed progression of hypometabolism in bilateral fronto-temporal cortex as well as basal ganglia with predominance at the left side (Fig. 1B). At this state, he was transferred to a rehabilitation hospital.

Tau protein is a neuronal microtubule-associated protein localized in the axon. It plays an important role in the assembly of tubulin monomers into microtubules to constitute the neuronal microtubules network and maintain structures.9 They are translated from a single gene located on chromosome 17q21. Their expression is regulated by alternative mRNA splicing mechanism. Six different isoforms of Tau exist in the human adult brain. Alternative splicing of Exons 2 (E2), 3 (E3), and 10 (E10) gives rise to six tau isoforms that differ in the number (three or four) of tubulin-binding domains/repeats (R).910 Taupathies are a group of disorders with common abnormal accumulation of tau protein in the brain.11 The relative amount of each isoform can vary with certain diseases. In Alzheimer's disease, insoluble tau contains both 3R and 4R isoforms, whereas 4R-tau isoforms are predominantly accumulated in PSP or CBD or FTD whose clinical presentation was described in our case.10 Previous studies have suggested that there is considerable overlap in the clinical and pathological features of PSP, CBD, and some forms of FTD. From this point of view, these disorders should be viewed as part of the same disease spectrum. Regarding clinical overlapping, so many large scale epidemiologic studies have been conducted on the prevalence of FTD-PSP-CBD. A prospective cohort study by Kertesz et al.12 has described the clinical evolution of FTD, which could shed light on such clinical overlapping. When PPA was present at the initial clinical presentation (n=22), nine of them evolved to CBD/PSP. If initial clinical presentation was CBD (n=4), all of them eventually progressed to PPA syndrome within 4 to 6 months from disease onset. When it comes to PSP as initial clinical syndrome (n=2), one of them revealed PPA after 6 months. Although, the number of patients was somewhat limited, it implicated that clinical presentation could frequently overlap regardless of the initial presentation. It has been reported that approximately 70% of patients with nfvPPA were found in heterogeneous pathology of PSP or CBD.13

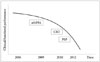

The nfvPPA is a progressive disorder with expressive language dysfunction among classical subtypes of FTD. According to the diagnostic criteria of nfvPPA, at least one of the agrammatism in language production or apraxia of speech must be present.2 In the case of our patient, language problem as the dominant feature was present at the beginning of the disease process. His speech was non-fluent and effortful with intermittent paraphasia, whereas his comprehension was relatively spared. Therefore, diagnosis for nfvPPA was acceptable.3 For an imaging-supported diagnosis, the case showed left posterior frontal and insular hypometabolism on PET scan. As time went by, motor symptoms such as mild rigidity and bradykinesia without other parkinsonism appeared more significantly at the right extremity which was not improved with adequate dose of levodopa. According to the Cambridge criteria, these symptoms were included in the major criteria of motor feature and in the minor criteria of cognitive features.14 CBD was considered as the clinical diagnosis at that stage. After about one year, the patient encountered postural instability with frequent falling and vertical gaze palsy. These features (Fig. 3, Table 2) appeared to be related to PSP.15

This case demonstrated the clinical course of a progressive tau-pathologic disorder in a patient with speech difficulty at the initial stage. Although this might not be an extremely rare case, it illustrated an actual longitudinal progression of the clinical, neuropsychological, and laboratory aspects of the disease with multiple follow-ups. Such illustrations are not so frequently reported. This could help us understand the tauspectrum disorder and the substantial overlap of clinical features among taupathies even in a single patient. These characteristics of tau-spectrum disorder may lead clinician to make different clinical diagnosis depending on when the clinician actually examines the patient. Therefore, diagnosis could be changed across time. We need to approach the tau spectrum disorder with a variety of perspectives for its diagnosis and management. In order to make a definite diagnosis, pathognomonic findings such as astrocytic plaque for CBD or tufted astrocytes for PSP should be present in pathologic study.16 It is not uncommon that there might be some discrepancy between clinical diagnosis and pathologic finding. Therefore, pathologic studies are needed to confirm its diagnosis, especially for patient with various clinical spectrum, although pathologic studies are rarely performed in Korea. The findings of our case were compared to those of previously reported ones with pathologic confirmation showing similar clinical progression. Although pathologic findings were diverse for either PSP or CBD, neuroimaging findings had something in common: left dominant dysfunction or atrophy in the perisylvian area (Table 3). Despite of the clinical overlapping features, there is still not enough evidence to explain that neurodegenerative taupathies are one single disease. Hopefully, future research on different types of taupathies will lead to the development of diagnosing and treating method for patients with FTD, PSP, or CBD.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomopraphy scan. A: Initial image demonstrating hypometabolism in the left posterior frontal, temporal cortex, and left basal ganglia in 2009. B: Follow-up image revealing hypometabolism in bilateral frontal, temporal cortex, and basal ganglia in 2012.

Fig. 2

Brain fluid attenuated inversion recovery image. A: Axial image demonstrating diffuse cerebral atrophy with subtle asymmetric atrophy in the left perisylvian area. B: Midsagittal image demonstrating equivocal midbrain atrophy.

Fig. 3

Clinical diagnostic spectrum of the patient across time. CBD: corticobasal degeneration, nfvPPA: nonfluent/agrammatic primary progressive aphasia, PSP: progressive supranuclear palsy.

Table 3

Previously reported cases with the feature of tau spectrum disorder

CBD: corticobasal degeneration, CT: computed tomography, EOM: extra-ocular movement, FDG-PET: fludeoxyglucose (18F)-positron emission tomography, FTLD: frontotemporal lobe degeneration, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, nfvPPA: non-fluent/agrammatic primary progressive aphasia, OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder, PSP: progressive supranuclear palsy, SPECT: single photon emission tomography.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Original Technology Research Program for Brain Science through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. 2014M3C7A1064752).

References

1. Seelaar H, Rohrer JD, Pijnenburg YA, Fox NC, van Swieten JC. Clinical, genetic and pathological heterogeneity of frontotemporal dementia: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011; 82:476–486.

2. Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011; 76:1006–1014.

3. Grossman M. The non-fluent/agrammatic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Lancet Neurol. 2012; 11:545–555.

4. Gorno-Tempini ML, Murray RC, Rankin KP, Weiner MW, Miller BL. Clinical, cognitive and anatomical evolution from nonfluent progressive aphasia to corticobasal syndrome: a case report. Neurocase. 2004; 10:426–436.

5. Kim HJ, Baik YJ, Jeong JH. A case of progressive supranuclear palsy with progressive non-fluent aphasia. Dement Neurocognitive Disord. 2007; 6:77–80.

6. Raggi A, Marcone A, Iannaccone S, Ginex V, Perani D, Cappa SF. The clinical overlap between the corticobasal degeneration syndrome and other diseases of the frontotemporal spectrum: three case reports. Behav Neurol. 2007; 18:159–164.

7. Kertesz A, McMonagle P, Jesso S. Extrapyramidal syndromes in frontotemporal degeneration. J Mol Neurosci. 2011; 45:336–342.

8. Kertesz A, Poole E. The aphasia quotient: the taxonomic approach to measurement of aphasic disability. 1974. Can J Neurol Sci. 2004; 31:175–184.

10. Bouchard M, Suchowersky O. Tauopathies: one disease or many? Can J Neurol Sci. 2011; 38:547–556.

11. Spillantini MG, Goedert M. Tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013; 12:609–622.

12. Kertesz A, McMonagle P, Blair M, Davidson W, Munoz DG. The evolution and pathology of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2005; 128(Pt 9):1996–2005.

13. Josephs KA, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Whitwell JL, Duffy JR, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of frontotemporal and corticobasal degenerations and PSP. Neurology. 2006; 66:41–48.

14. Mathew R, Bak TH, Hodges JR. Diagnostic criteria for corticobasal syndrome: a comparative study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012; 83:405–410.

15. Williams DR, Lees AJ. Progressive supranuclear palsy: clinicopathological concepts and diagnostic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2009; 8:270–279.

16. Yoshida M. Astrocytic inclusions in progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. Neuropathology. 2014; 34:555–570.

17. Armstrong MJ, Litvan I, Lang AE, Bak TH, Bhatia KP, Borroni B, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology. 2013; 80:496–503.

18. Litvan I, Agid Y, Calne D, Campbell G, Dubois B, Duvoisin RC, et al. Clinical research criteria for the diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome): report of the NINDSSPSP international workshop. Neurology. 1996; 47:1–9.

19. Mimura M, Oda T, Tsuchiya K, Kato M, Ikeda K, Hori K, et al. Corticobasal degeneration presenting with nonfluent primary progressive aphasia: a clinicopathological study. J Neurol Sci. 2001; 183:19–26.

20. Mochizuki A, Ueda Y, Komatsuzaki Y, Tsuchiya K, Arai T, Shoji S. Progressive supranuclear palsy presenting with primary progressive aphasia--clinicopathological report of an autopsy case. Acta Neuropathol. 2003; 105:610–614.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download