INTRODUCTION

Hospitalized patients are at high risk of malnutrition during hospitalization, and malnutrition in these patients are significantly associated with increased morbidity, mortality, hospital stay, and hospital costs [

1]. In particular, pediatric patients are highly susceptible to nutritional deficiencies, and the impact of malnutrition can be greater in this population than in adult patients. Poor nutritional status of hospitalized children is directly related to poor short-term disease outcomes. This can also affect long-term outcomes by delaying physical growth and neurocognitive development in these patients [

2]. The estimated prevalence of malnutrition among hospitalized children ranges between 12% and 24%, even in developed countries; however, the risk of malnutrition is often under-recognized and overlooked in hospitals [

3]. For these reasons, the necessity of a systematic nutritional support for hospitalized children has been emphasized for decades [

2].

According to a report from the Council of Europe in 2002, practices related to nutritional care and support of hospitalized patients, such as the use of nutritional risk screening and assessment, the assignment of responsibilities in nutritional support, and educational programs regarding clinical nutrition, were limited and insufficient, even in European countries [

4]. South Korea is one of the developed countries in Asia. While medical resources and medical standards are rapidly improving, conditions for nutritional support among hospitalized children seem to be generally insufficient, although this has yet to be evaluated.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the nutritional support status of hospitalized children in South Korea by conducting a nationwide hospital-based survey, in order to assist physicians in the recognition of malnourished pediatric patients.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Hospitals in South Korea are known for their qualified doctors, fast service, and well-equipped large-scaled facilities [

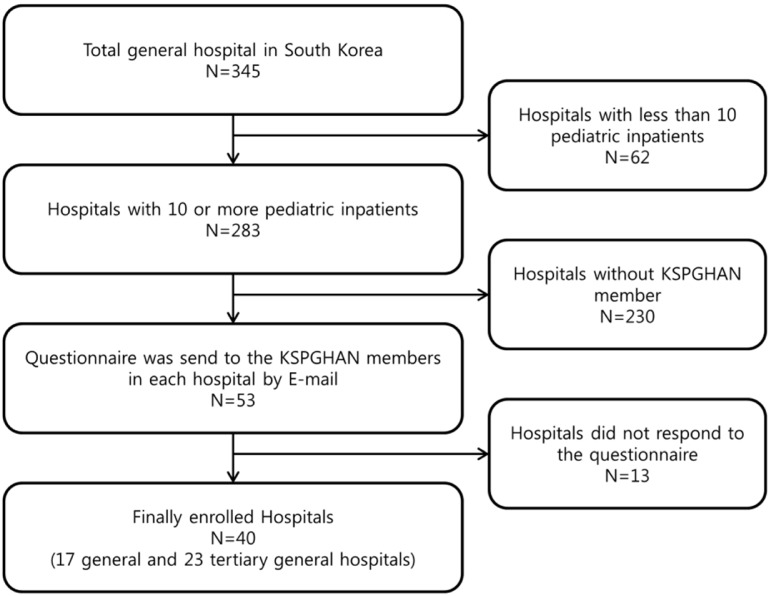

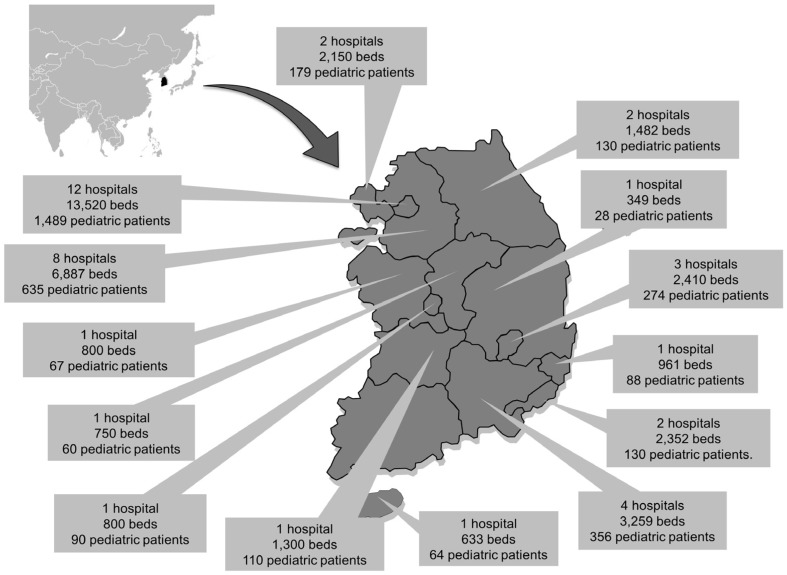

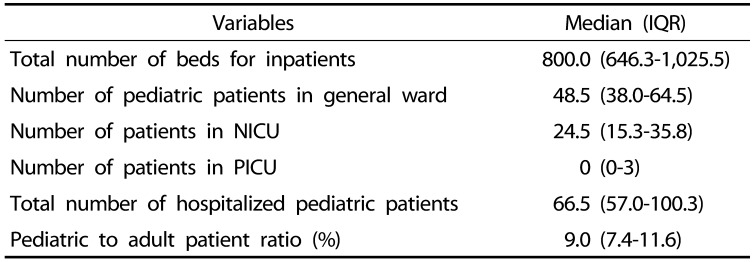

5]. According to data from the Ministry of Health and Welfare in South Korea, 364,189 foreign patients visited South Korea annually for medical services, and the number is increasing by approximately 30% every year. Although hospitals in South Korea are gradually evolving to global standards, nutritional care and attention to clinical nutrition among hospitalized patients is relatively insufficient, and even associated studies are scarce. In the present study, a total of 40 general hospitals were investigated through a nationwide hospital-based survey. The results of our study may represent approximately 12% of the total general hospitals (345 hospitals) in South Korea. This is the first study to investigate the status of nutritional support for hospitalized pediatric patients in South Korea. We aimed to determine the current status of nutritional support for hospitalized children through this nationwide hospital-based survey.

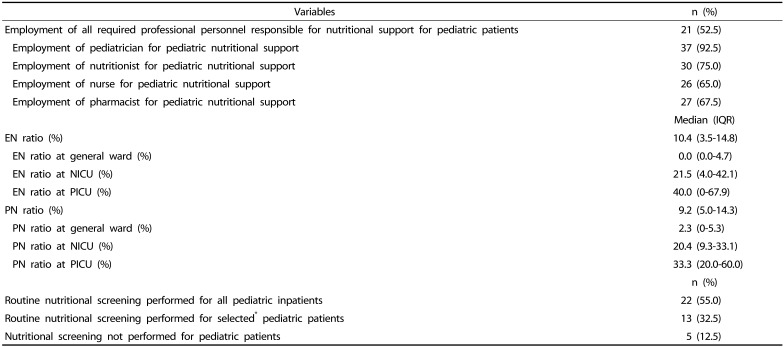

As reported by the ESPGHAN committee on nutrition, experienced physicians, nutritionists, nurses, and pharmacists encompass the ideal members of nutritional support [

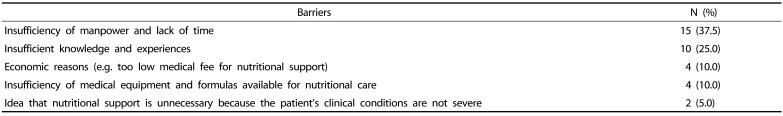

2]. However, according to our study, only half of general and tertiary hospitals in South Korea met this condition. Even when various medical conditions in each hospital were taken into account, this is still low, considering the size of the hospitals. In 8 hospitals, no personnel was assigned for nutritional care other than physicians. These findings suggest the future direction of the nutritional support system in Korean hospitals. Even if members of nutritional support team are able to care for adult patients, all possible professional health care providers should be assigned to pediatric nutrition, as manpower is the cornerstone of nutritional support. Consultation on nutritional support is available only when human resources and nutritional consultation system are in place and satisfactory clinical outcomes from nutritional support may result in additional consultations. Through this virtuous cycle, experience and knowledge can be accumulated and linked to high-quality nutritional support. In our nationwide hospital-based study, the most frequently encountered barrier to in-hospital nutritional support was the lack of manpower and time. Similarly, Ladas et al. [

6] reported that the biggest obstacle to nutritional care was the limited availability of registered dieticians.

EN and PN are essential parts of nutritional support [

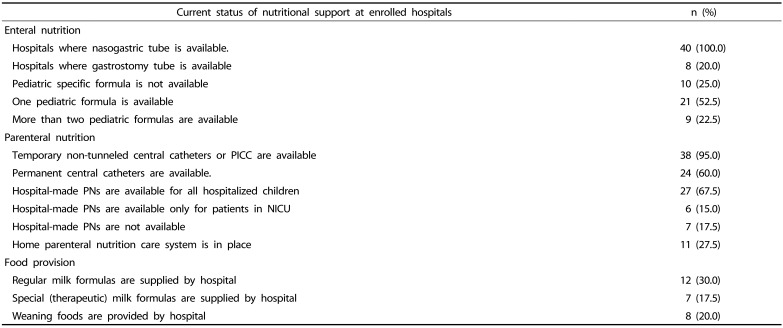

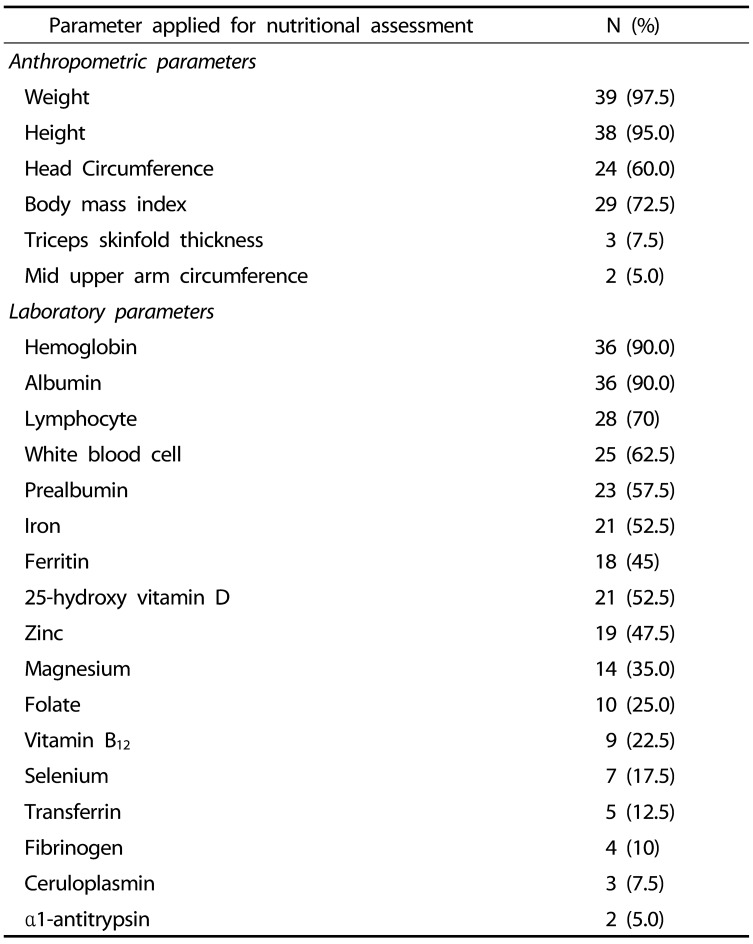

7]. Since the characteristics of patients differed, the proportion of EN and PN prescriptions varied from hospital to hospital in the present study. In all hospitals, it was possible to use short-term nasogastric tubes for enteral feeding. Although gastrostomy feeding should be used for prolonged enteral feeding [

8], gastrostomy tube was not available for pediatric patients in approximately 20% of hospitals. In addition, compared to adult EN formulas, few varieties of EN formulas were available for children. Furthermore, as EN formulas specified for childhood diseases were not available in many hospitals, disease-specified adult EN formulas were inevitably initiated on children.

In terms of PN supply, not every hospital used permanent central catheters. Customized hospital PN preparations for pediatric patients were available in 67.5% of hospitals. Since manufactured PN products are generally made for adult patients, the amount of calories and electrolytes contained is suitable for patients with larger physique. Therefore, for small pediatric patients, personalized hospital-made PN formula for each patient is required for ideal PN support. However, the provision of individualized, hospital-made PN was limited in several hospitals. Although the absolute number of pediatric patients is much less than that of adult patients and the profitability may be much less accordingly, manufacturers should make an effort to produce more variety of products for children. Hospitals should also attempt to provide optimal nutritional formula for each patient. The government may play a role in mediating any potential economic and ethical conflicts.

Experts agree that early interventions ensure the effectiveness of nutritional therapy [

9]. Furthermore, according to a nationwide study in Asia, whether or not to perform nutritional screening as a routine has a major impact on nutritional work processes and the methods of nutritional support [

10]. That is why guidelines emphasize on routine nutritional screening on admission [

11]. In the present study, routine nutritional screening for all hospitalized children was performed in approximately half of the hospitals, which was relatively lower than that in adult patients (55.3%

vs. 65.8%). According to a European study, nutritional screening on admission was performed routinely in 21–73% of hospitals [

12]. Although these rates were similar to ours, it should be highlighted that this European study was conducted approximately a decade before our survey. Nutritional screening process for pediatric patients should therefore be improved for proper nutritional support during hospitalization in Korea.

Several nutritional screening tools for adult patients are widely used in clinical practice. However, no widely-used nutritional screening tools are available for children, even though this population is vulnerable to malnutrition [

13]. While pediatric nutritional risk score, subjective global nutrition assessment, STAMP, PYMS, and STRONGkids have been developed as pediatric nutrition screening tools for children, there are no standardized approaches [

14]. According to our study, screening tools also varied between hospitals in Korea. Most hospitals used their own screening methods instead of the above-mentioned tools. In order to provide well-organized nutritional support, guidelines for standardized nutritional screening should be developed for hospitalized Korean children. Furthermore, this should not only be applied to newly-hospitalized patients, but also patients who have been hospitalized for longer periods, who may require screening on a regular basis.

Reluctance to change, lack of knowledge, lack of defined responsibility, lack of defined protocols, and overload of daily work were listed as the main barriers to an effective in-hospital nutritional support, according to the Italian study [

15]. Similarly, in our nationwide hospital-based survey, lack of manpower, time, as well as financial and medical resources, were reported as major barriers. These barriers cannot be solved without the multifaceted involvement of the hospitals or government, as manpower and medical resources are mainly concentrated in adult patients rather than in children, who make up a relatively smaller sized population in many countries.

There are several limitations to our study. First, because the questionnaires were sent to pediatric gastroenterologists, who are KSPGHAN members and also already invested in pediatric nutrition, the results of this survey may have overestimated the actual status of nutritional support for pediatric inpatients. Second, since some hospitals did not respond to the survey, our results may not reflect the overall condition of in-hospital nutritional support. Third, although the questionnaire was made through several intensive discussions and pilot surveys, the reliability and validity of the questionnaire could not be analyzed statistically, as the number of relevant subjects and existing data were limited. Additional communications between the enrolled subjects and the nutritional committee was carried out to complement this limitation.

In conclusion, nutritional support systems varied among hospitals and were often inadequate to provide sufficient nutritional care to hospitalized pediatric patients. Educational, financial, and administrative support is required for optimal nutritional management of hospitalized pediatric patients.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download