Abstract

Purpose

This cross-sectional study aimed to document the dietary behaviors, dietary changes, and health status of female marriage immigrants residing in Gwangju, Korea.

Methods

The survey included 92 female immigrants attending Korean language class at a multi-cultural family support center. General characteristics, health status, anthropometric data, dietary behaviors, and dietary changes were collected.

Results

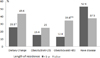

Mean age of subjects was 31.3 years, and home countries of subjects were Vietnam (50.0%), China (26.0%), Philippines (12.0%), and others (12.0%). Frequently reported chronic diseases were digestive diseases (13.2%), anemia (12.1%), and neuropsychiatry disorder (8.9%). Seventeen percent of the subjects was obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2). Dietary score by Mini Dietary Assessment was 3.45 out of 5 points. Dietary scores for dairy foods, meat/fish/egg/bean intake, meal regularity, and food variety were low, and those for fried foods and high fat meat intake were also low. Thirty-three percent of subjects answered that they have changed their diet and increased their consumption of fruits and vegetables after immigration. Length of residence in Korea was positively associated with BMI and waist circumference. Length of residence tends to be positively associated with dietary changes and obesity as well as inversely associated with disease prevalence.

Conclusion

The study shows that length of residence is inversely related to disease prevalence. However, this association is thought to be due to the relatively short period of residence in Korea and thus the transitional phase to adapting to dietary practices. As the length of residence increases, disease patterns related to obesity are subject to change. Healthy dietary behaviors and adaptation to dietary practices in Korea in female marriage immigrants will not only benefit individuals but also their families and social structure. Therefore, varied, long-term, and target-specific studies on female marriage immigrants are highly needed.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Dietary change, prevalence of obesity and disease by the length of residence in Korea1) % 2) Chi-square test

* p < 0.05

|

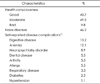

Table 3

Anthropometric data of female marriage immigrants

1) Mean ± SD 2) Significance determined by ANOVA (Analysis of variance) 3) Significance determined by ANCOVA (Analysis of covariance), age-adjusted 4) Different letters denote significant difference at p < 0.05 by Tukey test within the row. 5) NS: not significant 6) Mini dietary assessment score (5 = mostly, 3 = sometimes, 1 = rarely)

* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

References

1. Statistics Korea. International marriage: 2015 [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;cited 2016 May 10. Available from: http://www.index.go.kr/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do?idx_cd=2430.

2. So J, Han SN. Diet-related behaviors, perception and food preferences of multicultural families with Vietnamese wives. Korean J Community Nutr. 2012; 17(5):589–602.

3. Kim JM, Lee NH. Analysis of the dietary life of immigrant women from multicultural families in the Daegu area. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2009; 15(4):405–418.

4. Kim JM, Lee HS, Kim MH. Food adaptation and nutrient intake of female immigrantsinto Korea through marriage. Korean J Nutr. 2012; 45(2):159–169.

5. Han YH, Shin WS, Kim JN. Influential factor on Korean dietary life and eating behaviour of female marriage migrants. Comp Korean Stud. 2011; 19(1):115–159.

6. Jeong MJ, Jung EK, Kim AJ, Joo N. Nutrition knowledge and need for a dietary education program among marriage immigrant women in Gyeongbuk region. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2012; 18(1):30–42.

7. Kim SH, Kim WY, Lyu JE, ChungHW , Hwang JY. Dietary intakes and eating behaviors of Vietnamese female immigrants to Korea through marriage and Korean spouses and correlations of their diets. Korean J Community Nutr. 2009; 14(1):22–30.

8. Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M. Changes in dietary habits after migration and consequences for health: a focus on South Asians in Europe. Food Nutr Res. 2012; 56:18891.

9. Yun JW, Kang HS. Factors influencing married immigrant women’s perceived health status: the national survey of multicultural families 2012. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2015; 21(1):32–42.

10. Kim WJ. Social participation and health among female marriage immigrants in South Korea. J Community Welf. 2014; 48:77–103.

11. Cho JE, Cho GJ. A study on changes of the effect of factors to married immigrant women’s health: multicultural families survey (2009, 2012). J Migr Soc. 2014; 7(2):5–28.

12. Yang SJ, Chee YK, Kim JA, An J. Metabolic syndrome and its related factors among Asian immigrant women in Korea. Nurs Health Sci. 2014; 16(3):373–380.

13. Yang EJ, Chung HK, Kim WY, Bianchi L, Song WO. Chronic diseases and dietary changes in relation to Korean Americans’ length of residence in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007; 107(6):942–950.

14. Yang EJ, Kim WY, Song WO. Health risks in relation to dietary changes in Korean Americans. Korean J Diet Cult. 2001; 16(5):515–524.

15. Seo IJ, Park JS. Health promoting behaviors, health problems and self-rated health status in female marriage immigrant in Korean. J Digit Converg. 2013; 11(4):369–382.

16. Kim HR, Yeo JY, Jung JJ, Baek SH. Health status of marriage immigrant women and children from multicultural families and health policy recommendations. Seoul: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2012.

17. Cha SM, Bu SY, Kim EJ, Kim MH, Choi MK. Study of dietary attitudes and diet management of married immigrant women in Korea according to residence period. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2012; 18(4):297–307.

18. Lee JS. The factors for Korean dietary life adaptation of female immigrants in multi-cultural families in Busan. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2012; 41(6):807–815.

19. Asano K, Yoon J, Ryu SH. Chinese female marriage immigrants' dietary life after immigration to Korea: comparison between Han-Chinese and Korean-Chinese. Korean J Community Nutr. 2014; 19(4):317–327.

20. Kim JE, Kim JM, Seo SH. Nutrition education for female immigrants in multicultural families using a multicultural approach: indepth interviews with female immigrants and nutrition education professionals. Korean J Nutr. 2011; 44(4):312–325.

21. Kim JK, Kim JM, Kim H, Chung HW, Chang N. Relationship between food and nutrient intake and the risk of hypertriglyceridemia in Vietnamese women residing in Bavi: the Korean genome and epidemiology study (KoGES). Korean J Nutr. 2013; 46(1):15–25.

22. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Health Statistics 2014: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI-2). Sejong: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2015.

23. Mohan V. Why are Indians more prone to diabetes. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004; 52(6):468–474.

24. Hwang JY, Lee H, Ko A, Han CJ, Chung HW, Chang N. Dietary changes in Vietnamese marriage immigrant women: the KoGES follow-up study. Nutr Res Pract. 2014; 8(3):319–326.

25. Tserendejid Z, Hwang J, Lee J, Park H. The consumption of more vegetables and less meat is associated with higher levels of acculturation among Mongolians in South Korea. Nutr Res. 2013; 33(12):1019–1025.

26. Kim JH, Lee MH. Dietary behavior of marriage migrant women according to their nationality in multicultural families. Korean J Community Nutr. 2016; 21(1):53–64.

27. Han YH, Shin WS, Kim JN. Special theme:multicultural society and the identity of migrants; influential factor on Korean dietary life and eating behaviour of female marriage migrants. Comp Korean Stud. 2011; 19(1):115–159.

28. Yoon EJ. The Korean diaspora: migration, adaptation, and identity of overseas Koreans. Korean J Sociol. 2003; 37(4):101–142.

29. Berry JW, Kalin R. Multicultural and ethnic attitudes in Canada: an overview of the 1991 national survey. Can J Behav Sci. 1995; 27(3):301–320.

31. Choi SH, Joo J, Lee YJ, Kim HS. Social welfare for women. Paju: Yangseowon;2009.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download