INTRODUCTION

Adequate nutrition behaviors during early adulthood are important for the long period of adulthood and disease prevention in midlife or later. College life is characterized by becoming independent, studying, extracurricular activities, part-time work on campus or outside, and preparation for the job. These influence the eating habits of female college students, characterized by skipping meals, not having a variety of foods, insufficient consumption of foods including fruits, vegetables or dairy foods, and frequent consumption of processed foods or convenience foods [

1,

2,

3].

With the rapid development of the food industry, increases in nuclear families and seeking convenience in dietary life, processed foods and convenience foods are more readily available in our society. To help consumers choose foods sensibly, it is necessary to provide nutrition information on processed foods or convenience foods. The nutrition label provides information regarding food products, including serving size, nutrient content in food products, and the percentage of daily values. In Korea, nutrition fact labeling was introduced in 1994 under the food sanitation act [

4]. Reading nutrition labels was related to decisions in food selection, food purchasing behaviors, and practicing healthy eating behaviors (e.g., decreased consumption of energy or sodium) [

5,

6]. One study also reported that nutrition label users had lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome than those who did not use or did not have knowledge of nutrition labels [

7]. Using nutrition labels will help consumers to choose or purchase foods sensibly and to practice desirable nutrition behaviors (e.g., eating adequate calorie or fat, etc.) accordingly. The results of the 2012 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), however, revealed that only 31.7% of adults aged 19 and over read nutrition labels when they selected processed foods; those who read nutrition labels was slightly higher (45.4%) in women aged 19-29 than adults aged 19 and over [

8].

To promote nutrition label use in selecting or purchasing processed foods, investigation of factors explaining nutrition label use is needed. Studies on nutrition label use have focused on examining the status of nutrition label use, knowledge about and perceptions of using nutrition labels, food consumption, and eating habits [

9,

10,

11]. Theory based research enables a systematic, comprehensive investigation of factors influencing nutrition behaviors. One of those theories, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), provides a framework for understanding factors regarding nutrition behaviors because it covers diverse motivational factors (e.g., beliefs) influencing health or nutrition behaviors while using a small number of constructs.

According to the TPB [

12,

13], the performance of a behavior is determined by one's intention to do it. A person's intention is determined by three factors: personal attitudes towards the behavior, subjective norms and perceived control over the behavior. This theory helps us to understand the causes of behavior by investigating salient information, which are the beliefs underlying the three factors. Attitudes towards the behavior are formed through beliefs regarding the consequences of a behavior (i.e., behavioral beliefs) and evaluation of those consequences. Subjective norms are influenced by normative beliefs regarding what significant others in one's environment think one should do and the motivation to comply with these significant others. Perceived behavioral control is formed through beliefs regarding skills or opportunities for the behavior (i.e., control beliefs) and perceived power of each control factor. The TPB has been used in explaining nutrition behaviors, such as dairy food consumption, adequate consumption of fruits and vegetables, family meal frequency, sugarsweetened beverage consumption, and intentions to breastfeed [

3,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

As the importance of using nutrition labels has received attention, studies on nutrition label use have been conducted in recent decades [

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, most of these studies, have focused on examining the status of nutrition label use, knowledge and perceptions of using nutrition labels [

19,

20]. Relatively few studies have been conducted using theories to identify factors explaining nutrition label use [

5,

23]. The purpose of this study was to examine if factors, mainly beliefs based on the TPB, were important in explaining nutrition label use in female college students. In this study, female college students were chosen as the subjects, since they are entering the period of adulthood in the lifecycle, having independence in food choice and eating behaviors. They were more likely to consume and enjoy snacks than male college students [

2]. In addition, nutrition behavior of young adult women, including female college students, is important because it will influence the food selection or nutrition behavior of future families as well as their food selection. Study findings will provide baseline data for development of nutrition education programs for promoting nutrition label use in female college students and young adult women.

DISCUSSION

This study focused on examining motivational beliefs associated with nutrition label use based on the TPB. The percentage of nutrition label users (37.8%) in the current study was lower than that reported in the previous studies [

8,

10]. Results of the 2012 KNHANES [

8] showed that 45.5% of women aged 19-29 years were nutrition label users. A study with female college students [

10] also reported that 47.3% used nutrition labels in purchasing processed foods. In a survey with adults in their twenties, approximately 43% had recognition of nutrition labels [

9]. In contrast, a study regarding the stages of change found that only 31.6% were nutrition label users (action or maintenance stage) while two-thirds of subjects were in the preaction stages (precontemplation, contemplation, or preparation stage) [

26]. Among the general characteristics examined in this study, subject's grade seemed to differ slightly by nutrition label use, although it did not reach statistical significance. Nutrition label users were more likely to be juniors and seniors than freshmen and sophomores.

About two-thirds of nutrition label users responded that they were interested in reading the calorie information in nutrition labels. Other nutrients of interest were fat, cholesterol, saturated fat, and carbohydrate/sugars. Interest in calorie or fat information might reflect the fact that young adult women are highly interested in weight control and accordingly want to reduce the intake of energy or fat. Similar to the current study, results of the 2012 KNHANES showed that adults aged 19-29 had interest in calorie (62.5%), fat (saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol), and sodium information on nutrition labels [

8]. In the current study, 85.6% of subjects mentioned that reading nutrition labels influenced their food selection. This finding indicates that checking nutrition labels influences the decision to select healthy foods, suggesting the need for nutrition education regarding nutrition label use. The response that nutrition label use influenced food selection was slightly higher than that reported in the 2012 KNHANES (78.6% of women aged 19-29) [

8].

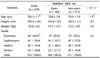

Nutrition label users showed significantly favorable beliefs toward use of nutrition labels in food selection compared with non-users (possible score: 15-75, 50.3 vs 48.5,

P < 0.01). Among the behavioral beliefs, nutritional benefits were motivators for using nutrition labels. Nutrition label users, compared to non-users, felt more strongly regarding the immediate advantages of checking nutrition labels, such as 'comparing foods and selecting better foods' and 'selecting healthy foods'. In contrast, belief strength regarding long-term benefits (e.g. disease prevention) did not differ between the two groups. These results suggested that nutrition education for nutrition label use should focus on the short-term, immediate benefits rather than the long-term, distant benefits for young adult women. Similarly, a study with college students reported that reasons for reading nutrition labels were mainly 'for checking the nutrient content', 'for weight control', 'to compare products or processed foods', and 'for health' [

1,

22]. Another study reported that expectation for nutrition or health benefits based on food labeling had an impact on the attitudes and intention to purchase products [

5]. A previous study found that young adults, compared to middle-aged adults, had lower perception regarding food, nutrition, and health, suggesting a relatively low level of interest in health among young adults [

27]. In one study, nutrition label users perceived the importance of checking nutrition labels more strongly than non-users and nutrition label use showed positive correlation with diet quality [

26]. Among seven negative beliefs regarding nutrition label use, non-users, compared to users, agreed more strongly on the item 'checking nutrition label is annoying'. Similarly, previous studies found that reasons for not using nutrition labels were 'habit' and 'annoying' [

10,

22]. Thus, nutrition education might focus on skills for more efficient use of nutrition information on labels based on one's health concerns.

This study found that nutrition label users, compared with their counterparts, perceived more pressure to use nutrition labels from parents, siblings, and one's best friend. However, the influence of health professionals, professors, and mass media was not significantly different between the two groups. This finding suggests that informal groups such as family members and friends are important sources to influence the use of nutrition labels in samples of young adult women. Previous studies using the TPB have suggested somewhat inconsistent results regarding the influence of significant others, partly supporting the results of the current study [

3,

14,

15,

16]. Subjective norms were found to be related to family meal frequency, and fruit and vegetable intake after the intervention [

15,

16], while other studies did not find an association between subjective norms and nutrition behaviors [

3,

14].

In this study, nutrition label users showed significantly higher perceived control beliefs than non-users (possible score: 15-75, 46.0 vs. 39.1,

P < 0.001). In addition, most of the control beliefs examined were significantly related to nutrition label use. These results indicated the importance of perceived confidence in performing the behavior, as suggested in the TPB [

12]. In the current study, control beliefs were measured in terms of perceived confidence in overcoming specific constraints or barriers to use of nutrition labels, and perceived confidence in understanding and using nutrition labels in food selection. Non-users, compared to users, perceived the constraints in using nutrition labels more strongly, such as 'spending more time on grocery shopping' and 'paying more money in selecting foods (i.e., more cost for healthy foods)' as a result of checking nutrition labels. In addition, the study results indicated that internal sources of control (e.g., one's knowledge level, the tendency to eat impulsively) rather than external sources (e.g., small font size, placing nutrition label on the back of the food package) were the factors differentiating nutrition label users from non-users. Perceived constraints such as 'small font size' and 'back-of pack nutrition labeling', cannot be solved by an individual's efforts, thus these control beliefs might not be different between the two groups. However, these constraints might be improved through policy or environmental changes to promote nutrition label use. Contrary to this study, previous studies reported that 'the font size in nutrition label is too small to read', and 'nutrition label is too complex to use' were reasons for not using nutrition labels [

10,

22].

This study also found that perceived confidence in understanding the specifics of nutrition labels and selecting foods accordingly was significantly related to nutrition label use (

P < 0.001). The study finding is consistent with the previous finding that self-efficacy to reduce fat intake was related to nutrition label use [

28]. The study population is young adult women attending college, thus, nutrition education regarding the specifics of nutrition labels and teaching skills in selection of foods based on nutrition labels would be effective in helping young adult women to select foods using nutrition labels. Similar to the current study, several previous studies applying the TPB suggested that perception of control was a significant factor in influencing nutrition behaviors including dairy food consumption, fruit and vegetable consumption, having family meals frequently, breakfast consumption, and safe food handling [

3,

14,

16,

28,

29,

30]. The study findings implied that methods to increase the perception of control over using nutrition labels should be incorporated in nutrition education.

The limitation of this study is that study results are based on a convenience sample of female college students who agreed to participate in the study in Seoul, Korea. Thus, the findings might not be generalized to different groups of young women.

In summary, this study suggested that factors, including behavioral, normative, and control beliefs need to be considered in development of nutrition education for promoting nutrition label use in female college students. Most of all, nutrition education might focus on increasing perceived control over nutrition label use. Specifically, nutrition education planning is needed in order to help young adult women to attain clear knowledge regarding nutrition labels (e.g., the meaning of a serving size, nutrient content, % daily value, etc.) and to apply knowledge of nutrition labels in selection of healthy snacks or purchasing processed foods. The perception of control over the constraints of using nutrition labels might be strengthened by providing methods to reduce the barriers (e.g., time, cost, preference for specific foods), such as reading information on the nutrient of concern, comparing prices of similar products, and recognizing the value on health. In addition, nutrition educators might include strategies to address the short-term benefits rather than long-term benefits of using nutrition labels (e.g., comparing and selecting better foods, selecting healthy foods vs. disease prevention) as well as reducing the perceived disadvantages of nutrition label use (e.g., it is annoying). Finally, informal groups, such as parents, siblings, and one's best friend might be considered as appropriate channels to promote nutrition label use in food selection for this population.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download