This article has been corrected. See "Erratum: Nutrient intakes of infants with atopic dermatitis and relationship with feeding type" in Volume 9 on page 213.

Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

The prevalence of atopic dermatitis in infants is increasing worldwide. However, the nutrient intake status of infants with atopic dermatitis has not been studied properly. This study was conducted to compare the nutrient intake status of infants in the weaning period with atopic dermatitis by feeding type.

MATERIALS/METHODS

Feeding types, nutrient intake status and growth status of 98 infants with atopic dermatitis from age 6 to 12 months were investigated. Feeding types were surveyed using questionnaires, and daily intakes were recorded by mothers using the 24-hour recall method. Growth and iron status were also measured.

RESULTS

The result showed that breastfed infants consumed less energy and 13 nutrients compared to formula-fed or mixed-fed infants (p < 0.001). The breastfed group showed a significantly lower intake rate to the Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans than the other two groups (p < 0.001). In addition, they consumed less than 75% of the recommended intakes in all nutrients, except for protein and vitamin A, and in particular, iron intake was very low, showing just 18.7% of the recommended intake. There was no significant difference in growth by feeding type, but breastfed infants showed a significantly higher rate of iron deficiency anemia (p < 0.001).

Atopic dermatitis is a type of chronic relapsing eczema accompanying itchiness, which is one of the allergic diseases [1]. The prevalence of allergic diseases including atopic dermatitis is increasing worldwide [2,3], and the attack rate in infants and children is two or three times higher compared to the attack rate in adults [4].

Relations between atopic dermatitis and food are very high [5,6,7], and major antigenic foods include eggs, milk, soybeans, peanuts etc. [8,9,10]. These foods are good suppliers of nutrients for growth of infants and therefore the nutrition deficiency due to the limitation of such foods was suggested one of the risk factors for growth retardation in infants with atopic dermatitis [11,12,13,14,15]. Many studies have found that infants and children with atopic dermatitis experienced retarded growth compared to their peer groups [15,16,17,18,19].

Breastfeeding is known to reduce the incidence of allergic diseases [20]. At least four months of breastfeeding after birth was more effective to decrease the incidence of atopic dermatitis [21] and a two-year cohort study with 4,089 newborn babies showed that breastfeeding only prevented early incidence of allergic disease including atopic dermatitis [22]. For this reason, breastfeeding is recommended for infants with atopic dermatitis [23].

Breast milk is superior to milk formulas because it includes nutrients and immune properties, which are essential for infants to grow and develop for one year [24]. However, five months after birth, nutrient level in breast milk starts to decrease and iron and other minerals, protein and vitamins become insufficient, so, from 4-6 months after birth, baby food should be provided to infants while continuing breastfeeding, to encourage them to consume proper food according to their growth [25,26]. Only breastfeeding more than six months or a belated start to baby food intake may lead to nutrient deficiency [27]. In the case of infants with atopic dermatitis, limitation of foods, which cause allergies, is common, which results in a longer breastfeeding period compared to their normal peers. Failure to change from breastfeeding to baby food intake in time could put infants in danger of nutrient deficiency.

Moreover, when mothers breastfeed babies with food allergies, they are advised to carry out dietary restriction. Because it was found that proteins in antigenic foods, such as eggs, milk, wheat, peanuts, etc., were transferred to infants through breast milk and caused a food allergy [28,29]. Thus, infants with atopic dermatitis breastfed by mothers with a limited diet have more chance to consume relatively less nutritious breast milk. Nutrient shortage from breastfeeding accompanied with a lack of proper baby food may have a negative effect on the growth of infants with atopic dermatitis.

Until now, studies about the effects of breastfeeding on the incidence of atopic dermatitis among infants have actively been performed [20,21,22,23], but the nutrient intake status of infants with atopic dermatitis has not been studied properly. With regard to feeding type, studies have found influences of different feeding type (i.e. breastfeeding, formula-feeding or mixedfeeding) on nutrients intakes and growth patterns in healthy infants through the first year of life [30,31,32]. However, there is no comparison analysis of the effect of feeding type on nutrient intakes of infants and children with atopic dermatitis. This study investigated feeding types and dietary intake status in infants with atopic dermatitis between the ages of 6 months and 12 months, who are in the weaning period, and compared their nutrient intake and growth status by feeding type. We aimed to identify the problems in nutrient intakes of infants with atopic dermatitis by feeding type and to propose direction for improvement in dietary intervention and nutritional education for infants with atopic dermatitis.

The subjects of this study were 98 infants with atopic dermatitis between the ages of 6 months and 12 months. The subjects were recruited among infants at that age, who visited the allergy center of a hospital in Seoul from January 2011 to November 2011. A food allergy of the subjects was diagnosed using blood tests and food challenges. The subjects were divided into three groups: breastfed (exclusively breastfed), formula-fed (exclusively formula-fed) and mixed-fed group (both breastfed and formula-fed). The protocol of the present study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center.

For survey, self-administered questionnaires were given to the mothers of the 98 subjects. The questions consisted of general characteristics of the subjects such as sex and age, feeding type, feeding frequency, feeding time, feeding amount and baby food start period. Dietary intakes of the subjects were investigated using the 24-hour recall method, and the mothers were asked to record all foods that the subjects consumed for one day. Food models, pictures of different portion sizes of dishes and detailed instruments were used to maximize the accuracy in estimation of the quantity of food consumed. With regard to the amount of breast milk intake, the intake of average Korean infant per day of 750 ml [33], feeding frequency per day of 7.2-9.2 times and average feeding time of 15 minutes [34] were assumed, and the amount of breast milk per one feeding was calculated as 100 ml. Physical measurements and blood samples were taken to assess the growth status of the subjects. Their heights and weights were measured by a professional nurse in the allergy center and blood samples were taken by a pediatrician.

Dietary intake data provided from the 24-hour recall method was analyzed using CAN-pro 3.0, professional software for nutrient calculation. Nutrients in breast milk not included in the CAN-pro 3.0 database were calculated referring to foreign literature [35,36].

Dietary intakes of the subjects were calculated, being classified as energy and 13 nutrients (protein, calcium, phosphorus, iron, zinc, vitamin A, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, niacin, vitamin C, folic acid and vitamin D). Also, the data "Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans" was used to assess the nutrient intakes of the subjects. Energy was calculated as intake rate against Estimated Energy Requirement (EER), and the other 13 nutrients were calculated as intake rates against Recommended Intake (RI) or Adequate Intake (AI) according to age.

With regard to growth of the subjects, heights and weights of the subjects were compared with the Children Growth Standard, referring to 2007 Korean National Growth Charts [37]. Measurements were converted to Z-scores for height for age (HAZ), Z-scores for weight for age (WAZ) and Z-scores for weight for height (WHZ). Subjects with Z-scores between -1SD and 1SD were classified as 'normal group in nutrition, and subjects with lower than -1SD or higher than 1SD of Z-scores were classified as 'group with a risk of nutrient deficiency' or 'group with a risk of overnutrition' respectively. To assess anemia status, hemoglobin and hematocrit levels in venous blood samples were examined using an automatic blood analyzer. Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) was identified as lower than 11.5g/dl of hemoglobin level and lower than 35% of hematocrit level [38].

All data was statistically analyzed using SPSS for Window 18.0. The subjects were divided into a breastfed group, formula-fed group and mixed-fed group for comparison analysis. Analyzed results were presented as frequency and percentage or mean and standard deviation. The Chi-squared test or ANOVA (Duncan's multiple range test) was used to check if there are significant differences among the three groups.

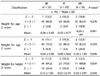

The general characteristics of subjects are shown in Table 1. The number of boys was greater than the number of girls; among the total of 98 subjects, boys comprised 64 (65.3%) and girls 34 (34.7%). The average age of the subjects was 7.7 months, with 54 infants (54.1%) at the age of 6-8 months and 44 infants (44.9%) at the age of 9-12 months. The average height was 70.0cm and the average weight was 8.6kg. More than a half of the subjects (54.1%) were breastfed, and 30% of the subjects were formula-fed and 16% mixed-fed.

Table 2 shows the daily nutrient intakes of subjects by feeding type. Energy intake of the breastfed group was significantly low compared to the formula-fed group or mixed-fed group (P < 0.001). With regard to protein, four minerals (calcium, phosphorus, iron and zinc) and eight vitamins (vitamin A, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, niacin, vitamin C, folic acid and vitamin D), the average intakes of the breastfed group were significantly insufficient compared to the other two groups (P < 0.001). In particular, the iron intake of a breastfed group was 1.1 mg, which is much less than the formula-fed group (6.3 mg) or mixed-fed group (4.5 mg).

The mean values of %RDA of daily nutrient intakes of subjects by feeding type were shown in Table 3. Intake rates to EER were 67.7%, 84.5% and 89.3% in the breastfed group, formula-fed group and mixed-fed group, respectively, showing insufficient intakes in all groups. The intake rate of the breastfed group was significantly lower than the other two groups (P < 0.001). Nutrient intakes in the formula-fed or mixed-fed group were near or over the recommended intake amount, except for iron. By and large, the intake rates to the recommended allowance in the formula-fed group were higher than the mixed-fed group, but there were no significant differences between the two groups except for iron. The breastfed group consumed less than 75% of the recommended intakes in all nutrients except for protein (79.6%) and vitamin A (84.7%). In particular, iron and vitamin D intake rates were very low, showing just 18.7% and 37.3%, respectively.

Table 4 shows the Z-score data for all anthropometric variables in each group of subjects. There were no significant differences in the growth status of the subjects by feeding type. Table 5 shows the iron status of subjects by feeding type. Iron status showed the significant differences between feeding type groups. The average hemoglobin levels of the breastfed, formula-fed and mixed-fed groups were 11.3 g/dl, 12.3 g/dl and 11.8 g/dl, respectively, and the level of the breastfed group was significantly lower than the formula-fed or mixed-fed group (P < 0.001). The average hematocrit levels of the breastfed, formula-fed and mixed-fed groups were 34.5%, 37.0% and 35.4%, respectively, and the breastfed group showed a significantly lower level than the formula-fed or mixed-fed group (P = 0.001). In the breastfed group, 43.4% of subjects recorded a lower hemoglobin level than a normal level (< 11.5 g/dl), and 58.5% of the subjects showed lower than 35% in the hematocrit level, which means almost a half of the breastfed group has iron deficiency anemia.

According to the feeding type survey on 98 infants with

atopic dermatitis in the weaning period, the rate of breastfeeding and mixed-feeding was 70.4%, much higher than formula-feeding (29.6%). Only breastfeeding accounted for more than a half. Compared to the 36.2% of breastfeeding for six months in Korean mothers in 2011 [39], the rate of breastfed infant among the subjects at the age of 6-12 months in the current study was noticeably high. The result seems to come from the recent campaign to recommend breastfeeding in Korea and the recognition of mothers about immune properties of breast milk to enhance prevention of atopic dermatitis [22].

However, compared to the formula-fed group or mixed-fed group, nutrient intake of the breastfed group was not desirable, showing insufficient intakes of energy and 13 minerals and vitamins. Energy intake of the breastfed was only 67.7% of EER, and average intakes of all nutrients, except for protein and vitamin A, did not reach even 75% of the RDA or Adequate Intake (AI). Infants with atopic dermatitis usually practice diet limitation to avoid allergenic foods and breastfed infants with atopic dermatitis, in particular, tend to fail to consume proper baby food, compared to their normal peers. It was reported that Korean infants with atopic dermatitis aged 0-36 months had insufficient energy and intakes of calcium, phosphorus, iron, zinc and vitamin B2 compared to the healthy infants [40]. Moreover, the previous study investigating nutrient intakes of healthy infants aged 4-9 months in relation to the feeding type showed that breast-fed infants tended to have lower intakes of energy and protein compared to infants formula-fed or mixed-fed [41]. Therefore, the results of the current study showed the possibility that infants with atopic dermatitis exclusively breastfed can be at risk for more severe multiple nutrient deficiencies compared to their peer group.

With regard to iron, intake status by feeding type was obviously different. The intake rate of the breastfed group was really serious, with less than 20% of RDA. The hemoglobin level and hematocrit level, which are important factors for diagnosing iron deficiency anemia, were lowest in the breastfed group. In addition, half the breastfed group had iron deficiency anemia, which means breastfed infants with dermatitis have a high risk of iron deficiency anemia.

Regardless of atopic dermatitis, the relation between breastfeeding and the lack of iron intake is well known [42]. Healthy breastfed babies store sufficient amount of iron from their mothers in their bodies, so they do not seem to suffer from iron deficiency until six months after birth, but from six months after birth, the iron level of breast milk sharply decreases [43]. Thus, if infants at the age of more than 6 months continue to be breastfed or eat iron-insufficient baby food, they have more possibility to experience iron deficiency anemia [44]. In the case of infants with atopic dermatitis, animal food, which is usually an allergic food but a major source of iron, is usually limited, so the risk of iron deficiency is even higher. Therefore, baby food increasing iron absorption rate should be provided to breastfed infants with atopic dermatitis, or if baby food intake is not available, iron supplements should be provided.

During weaning period, nutrient intake through dietary consumption becomes more important than breastfeeding for babies, so nutrient intake status through baby food or food supplements may influence the growth. Also, breastfeeding only for more than 6 months or belated consumption of baby food leads to nutrient deficiency [27]. In the current study, however, there were no significant differences in growth status of subjects by feeding type. It was reported no significant growth difference in healthy infants by feeding type from birth till sixth month of age, in spite of the significant lower intakes of energy and nutrients in breast-fed infants than in formula-fed infants [45]. Agostoni et al. [12] found that the early type of feeding seems to have only a marginal influence on growth in infants with atopic dermatitis during the first year of life.

None the less, atopic dermatitis is related to retarded growth [15,16]. Therefore, nutrition management programs should be developed to supplement insufficient nutrients, not only iron but other minerals and vitamins, for breastfed infants with atopic dermatitis.

Meanwhile, breastfeeding mothers are usually asked to limit their food intake because allergic food consumed by mothers can be transferred to infants through breast milk [28,29]. That results in a stronger likelihood that breastfeeding mothers will consume insufficient nutrients. It was reported that Korean breastfeeding mothers of normal infants consume insufficient energy and nutrients [46,47], so breastfeeding mothers of infants with atopic dermatitis, who practice food limitation, have a higher risk of nutrient deficiency. Nutrient deficiency in breastfeeding mothers may cause a decrease in the amount of breast milk and a change in the nutrient composition of breast milk, which directly affects the nutrient intake status of breastfed infants [48]. Breastfeeding mothers of infants with atopic dermatitis should avoid allergy causing foods but should also consume sufficient nutrients to provide healthy breast milk with a proper nutrient composition for their infants. Therefore, nutrition education and management to increase awareness of the importance of vitamin and mineral intake of breastfeeding mothers is needed. In addition, continuous management programs should be prepared for infants with atopic dermatitis, who are in a period when rapid growth takes place and proper nutrient intake is essential.

This study is meaningful in calling attention to the importance of nutritional education and intervention for breastfed infants with atopic dermatitis. However, caution should be taken when interpreting and generalizing the study results due to the limitation in the number of subjects. Breast milk intakes in infants were estimated by the feeding frequency per day and the average amount of breast milk per one feeding instead of measuring the real intake amounts. A single day dietary recall does not capture the usual intake of individuals because most individuals' diets vary day-to-day. Another limitation is that the dietary intake status of the subjects' mothers by feeding type was not investigated. Therefore, a broader and in-depth study about the effects of feeding types on the nutrient status of infants with atopic dermatitis should be conducted in the future, based on the results of this study, and an investigation into the diet quality of mothers of infants with atopic dermatitis should also be carried out.

Figures and Tables

References

2. Leung DY, Boguniewicz M, Howell MD, Nomura I, Hamid QA. New insights into atopic dermatitis. J Clin Invest. 2004; 113:651–657.

3. Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, Cookson W, Anderson HR. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase One and Three Study Groups. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 121:947–954.e15.

4. Schultz Larsen F, Hanifin JM. Secular change in the occurrence of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1992; 176:7–12.

5. Guillet G, Guillet MH. Natural history of sensitizations in atopic dermatitis. A 3-year follow-up in 250 children: food allergy and high risk of respiratory symptoms. Arch Dermatol. 1992; 128:187–192.

7. Ahn SH, Seo WH, Kim SJ, Hwang SJ, Park HY, Han YS, Chung SJ, Lee HC, Ahn KM, Lee SI. Risk factors of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in the first 6 months of life. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2005; 15:242–249.

8. Zeiger RS. Dietary aspects of food allergy prevention in infants and children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000; 30:Suppl. S77–S86.

9. Arshad SH. Food allergen avoidance in primary prevention of food allergy. Allergy. 2001; 56:Suppl 67. 113–116.

10. Finch J, Munhutu MN, Whitaker-Worth DL. Atopic dermatitis and nutrition. Clin Dermatol. 2010; 28:605–614.

11. Chung SJ, Han YS, Chung SW, Ahn KM, Park HY, Lee SI, Cho YY, Choi HM. Marasmus and kwashiorkor by nutritional ignorance related to vegetarian diet and infants with atopic dermatitis in South Korea. Korean J Nutr. 2004; 37:540–549.

12. Agostoni C, Grandi F, Scaglioni S, Giannì ML, Torcoletti M, Radaelli G, Fiocchi A, Riva E. Growth pattern of breastfed and nonbreastfed infants with atopic dermatitis in the first year of life. Pediatrics. 2000; 106:E73.

13. Baum WF, Schneyer U, Lantzsch AM, Klöditz E. Delay of growth and development in children with bronchial asthma, atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2002; 110:53–59.

14. Fleischer DM, Leung DY. Eczema and food hypersensitivity. In : Metcalfe DD, Sampson HA, Simon RA, editors. Food Allergy: Adverse Reactions to Foods and Food Additives. 4th ed. Malden (MA): Blackwell Pub.;2008. p. 110–112.

15. Palit A, Handa S, Bhalla AK, Kumar B. A mixed longitudinal study of physical growth in children with atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007; 73:171–175.

16. Mehta H, Groetch M, Wang J. Growth and nutritional concerns in children with food allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013; 13:275–279.

17. Pike MG, Chang CL, Atherton DJ, Carpenter RG, Preece MA. Growth in atopic eczema: a controlled study by questionnaire. Arch Dis Child. 1989; 64:1566–1569.

18. Patel L, Clayton PE, Addison GM, Price DA, David TJ. Linear growth in prepubertal children with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dis Child. 1998; 79:169–172.

19. David TJ, Ferguson AP, Newton RW. Nocturnal growth hormone release in children with short stature and atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991; 71:229–231.

20. Muraro A, Dreborg S, Halken S, Høst A, Niggemann B, Aalberse R, Arshad SH, von Berg A, Carlsen KH, Duschén K, Eigenmann P, Hill D, Jones C, Mellon M, Oldeus G, Oranje A, Pascual C, Prescott S, Sampson H, Svartengren M, Vandenplas Y, Wahn U, Warner JA, Warner JO, Wickman M, Zeiger RS. Dietary prevention of allergic diseases in infants and small children. Part II. Evaluation of methods in allergy prevention studies and sensitization markers. Definitions and diagnostic criteria of allergic diseases. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004; 15:196–205.

21. Schoetzau A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Franke K, Koletzko S, Von Berg A, Gruebl A, Bauer CP, Berdel D, Reinhardt D, Wichmann HE. German Infant Nutritional Intervention Study Group. Effect of exclusive breast-feeding and early solid food avoidance on the incidence of atopic dermatitis in high-risk infants at 1 year of age. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002; 13:234–242.

22. Kull I, Wickman M, Lilja G, Nordvall SL, Pershagen G. Breast feeding and allergic diseases in infants-a prospective birth cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2002; 87:478–481.

23. Friedman NJ, Zeiger RS. The role of breast-feeding in the development of allergies and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005; 115:1238–1248.

24. Yum H. Association of brestfeeding and allergic diseases. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2009; 19:325–328.

25. Sung YA, Ahn JY, Lee HY, Kim JY, Ahn DH, Hong YJ. A survey of breast-feeding. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1998; 41:444–450.

26. Kim YH. Pediatric Medical Nutrition. Seoul: Korea Medical Book;2007.

27. Ziegler EE, Nelson SE, Jeter JM. Iron status of breastfed infants is improved equally by medicinal iron and iron-fortified cereal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009; 90:76–87.

28. Duchén K, Björkstén B. Sensitization via the breast milk. In : Mestecky J, Blair C, Ogra PL, editors. Immunology of Milk and the Neonate. New York (NY): Plenum Press;1991. p. 427–436.

29. Fukushima Y, Kawata Y, Onda T, Kitagawa M. Consumption of cow milk and egg by lactating women and the presence of betalactoglobulin and ovalbumin in breast milk. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997; 65:30–35.

30. Dewey KG, Peerson JM, Brown KH, Krebs NF, Michaelsen KF, Persson LA, Salmenpera L, Whitehead RG, Yeung DL. Growth of breast-fed infants deviates from current reference data: a pooled analysis of US, Canadian, and European data sets. World Health Organization Working Group on Infant Growth. Pediatrics. 1995; 96:495–503.

31. Heinig MJ, Nommsen LA, Peerson JM, Lonnerdal B, Dewey KG. Energy and protein intakes of breast-fed and formula-fed infants during the first year of life and their association with growth velocity: the DARLING Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993; 58:152–161.

32. Gale C, Logan KM, Santhakumaran S, Parkinson JR, Hyde MJ, Modi N. Effect of breastfeeding compared with formula feeding on infant body composition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012; 95:656–669.

33. The Korean Nutrition Society. Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans. Seoul: The Korean Nutrition Society;2010.

34. Lee SI, Choi HM. Nutrition for infants and children. Seoul: Kyomunsa;2003.

35. Emmett PM, Rogers IS. Properties of human milk and their relationship with maternal nutrition. Early Hum Dev. 1997; 49:S7–S28.

36. Morgan JB, Dickerson JW. Nutrition in Early Life. Chichester: Wiley;2003.

37. Korean Pediatric Society. The Korean Standard Growth Data of Childhood and Adolescents. Seoul: Korean Pediatric Society;2007.

38. Dallman PR, Siimes MA. Percentile curves for hemoglobin and red cell volume in infancy and childhood. J Pediatr. 1979; 94:26–31.

39. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (FR). CO1.5 Breastfeeding rates [Internet]. Paris: OECD Family Database;2011. cited 2014 Nov 30. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/social/family/database.

40. Park SJ, Lee JS, Ahn K, Chung SJ. The comparison of growth and nutrient Intakes in children with and without atopic dermatitis. Korean J Community Nutr. 2012; 17:271–279.

41. Oh KH, Kim KS, Seo JS, Choi YS, Shin SM. A study on the nutrient intakes and supplemental food of infants in relation to the method of feeding practics. Korean J Nutr. 1996; 29:143–152.

42. Maguire JL, Salehi L, Birken CS, Carsley S, Mamdani M, Thorpe KE, Lebovic G, Khovratovich M, Parkin PC. TARGet Kids! collaboration. Association between total duration of breastfeeding and iron deficiency. Pediatrics. 2013; 131:e1530–e1537.

44. Chang JH, Cheong WS, Jun YH, Kim SK, Kim HS, Park SK, Ryu KH, Yoo ES, Lyu CJ, Lee KS, Lee KC, Lim JY, Choi DY, Choe BK, Choi EJ, Choi BS. Weaning food practice in children with iron deficiency anemia. Korean J Pediatr. 2009; 52:159–166.

45. Ahn HS, Bai HS. The longitudinal study of the growth by feeding practice in early infancy. Korean J Nutr. 1997; 30:336–348.

46. Kim WJ, Ahn HS, Chung EJ. Mineral intakes and serum mineral concentrations of the pregnant and lactating women. Korean J Community Nutr. 2005; 10:59–69.

47. Yoon JS, Jang HK, Park JA. A study on calcium and iron status of lactating women. Korean J Nutr. 2005; 38:475–486.

48. Kim KN, Hyun T, Kang NM. A survey on the feeding practices of women for the development of a breastfeeding education program: breastfeeding knowledge and breastfeeding rates. Korean J Community Nutr. 2002; 7:345–353.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download