Abstract

The purpose of this research was to investigate how university students' nutrition beliefs influence their health behavioral intention. This study used an online survey engine (Qulatrics.com) to collect data from college students. Out of 253 questionnaires collected, 251 questionnaires (99.2%) were used for the statistical analysis. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) revealed that six dimensions, "Nutrition Confidence," "Susceptibility," "Severity," "Barrier," "Benefit," "Behavioral Intention to Eat Healthy Food," and "Behavioral Intention to do Physical Activity," had construct validity; Cronbach's alpha coefficient and composite reliabilities were tested for item reliability. The results validate that objective nutrition knowledge was a good predictor of college students' nutrition confidence. The results also clearly showed that two direct measures were significant predictors of behavioral intentions as hypothesized. Perceived benefit of eating healthy food and perceived barrier for eat healthy food to had significant effects on Behavioral Intentions and was a valid measurement to use to determine Behavioral Intentions. These findings can enhance the extant literature on the universal applicability of the model and serve as useful references for further investigations of the validity of the model within other health care or foodservice settings and for other health behavioral categories.

Approximately two-thirds (65%) of U.S. adults over the age of 20 are overweight or obese. The prevalence of obesity has increased steadily in the U.S. over the last 30 years [1,2]. According to the 1976-1980 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey II (NHANES), 15% of adults over 20 years old were obese. In the 1988-1994 NHANES III, obesity rates increased to 23.3%. The most recent NHANES data indicated that over one-third (34%) of American adults are obese and the majority (65.7%) of American adults are either overweight or obese Although there was no significant increase, there was a continuous increase in the prevalence of obesity from the NHANES 2003-2004 study (30.6%) to the 2005-2006 study [2,3]

One quarter of all individuals aged 18-24 in the United States are currently enrolled in the nation's colleges and universities [4]. College students exhibit distinct decline in nutritional priorities, and poor eating habits often worsen during this time. A hallmark of most student diets is fast-food that is high in fat and sodium content [5]. In 2010, one study reported that most college students did not eat any fruit even once a day and about half of them ate vegetables less than once daily [6]. Because starting college often represents the first time many people assume primary responsibility for their meals, then food beliefs of college students are particular relevant. There are a lot of fast-food stores and restaurant near most campuses that can negatively effect on-campus foodservice business [7,8]. Since adequate nutrition is essential for maintaining health, decreasing existing health problems, maintaining functional independence, and improving nutritional status are seriously important to prolong good health status and well-being [9]. In addition, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that within the typical university years, the frequency of doing vigorous exercise three or more times a week declined 6.2 percentage points for men and 7.3 percentage points for women [4].

Originally, the health belisf model (HBM) was designed to describe a model of disease prevention, not a model of disease treatment. Health beliefs include an individual's perception of Susceptibility to, and Severity of, diseases or disorders as well as the perception of Benefits of, and Barriers to, taking action to prevent diseases or disorders [10]. These perceptions can be modified by the physical, social, and cultural environment. The perceptions of Susceptibility and Seriousness combine to form a perceived threat of a disease or disorder. If the perceived Benefits of taking preventive action to avoid a disease are viewed as greater than the perceived threat of the disease, the individual is likely to modify or engage in health behavior. If the perceived Barriers to taking preventive action are viewed more negatively than the harm from the resulting disease or condition, the individual is unlikely to modify or engage in healthy behavior. The perceived Benefits of healthy behaviors minus the perceived Barriers to the healthy behavior determine the likelihood of an individual taking preventative action.

Using the Health Belief Model, this study attempts (a) to investigate college students' health behavior, (b) to address the determinants of eating behavior and physical activity and (c) to assess if those underlying factors are interrelated. The insight into how and why health behaviors are developed is important to the success and adaptability of promoting healthy lifestyles to college students.

In order to address this study's objectives, quantitative methods were employed. A structured survey questionnaire was used to investigate several factors: (a) objective Nutrition Knowledge; (b) Nutrition Confidence; (c) Benefit, Barrier, Susceptibility, and Severity; (d) Behavioral Intention to Eat Healthy Food and Behavioral Intention to Do Physical Activity; and, (e) demographic information. For questionnaire validity and reliability, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and Cronbach's alpha test were employed.

Two pilot studies were conducted during the Fall 2009 and Spring 2010. The primary purpose of these studies was to determine whether the instrument could be clearly understood by respondents and to ensure reliability of the instrument. For the first pilot test, questionnaires were distributed to 20 graduate students. The data from the pilot study were analyzed and examined for frequency of the knowledge section and the reliability of the question scales. The second pilot test was conducted with 30 undergraduate. Using Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the item scales, all proposed factors reported above 0.70, with factor analysis verifying construct validity as well. The study used a convenience online sampling method. Questionnaires using an online survey engine (Qualtrics.com) were distributed to college students enrolled on 2010 spring semester. For instrument reliability and validity, more than 250 samples were required [8]. From 1st to 20th February 2010, six instructors were contacted with a request to distribute the questionnaire to 280 potential respondents in the Southwestern region of the United States. If the instructors used an online learning system such as Blackboard and WebCT, they posted the online survey webpage and URL with an announcement through their eLearning system. The remaining instructors sent an e-mail to their students with the recruitment message and URL for the survey.

A graphical representation of the specified model for this study can be seen in Fig. 1. It is a modification of the Rosenstock, Strecher and Becker studies on social learning and the Health Belief Model [10]. This model incorporates the objective nutrition knowledge as a predictor for nutrition confidence in the process of health belief and health Behavioral Intentions for respondents' health.

Using Qualtrics.com, 251 questionnaires were collected and used for the statistical analysis. SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to manage, screen, and analyze the data. Descriptive statistics of demographic variables were helpful in describing the sample, which aided in evaluating generalizability of the findings. Descriptive statistics including frequencies and measures of central tendencies (mean, median, mode) and dispersion (range and standard deviation) were used to explore and describe the demographic variables of age, race, classification, self-reported body image, and BMI. The demographic results for the sample were compared to the demographics of the university population to confirm that the sample was representative of the population being investigated.

Simple descriptive statistics tools such as frequency and percentage were used to describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. Forty-nine percent of the respondents were male students and 51% were female. Sixty-eight percent of the respondents were White and 15.1%, 12.4%, 2.8% and 1.6% were Asian, Hispanic, African-American, and other, respectively. The most frequently occurring classification group was Sophomore (41.8%), followed by Junior (21.5%), Senior (21.1%), Graduate (11.2%) and Freshman (4.4%). The average of the all respondents' age was 21.98 (SD = 3.783). Moreover, the independent t-test revealed that there is a significant difference (t (231.20) = 3.22, P < 0.001) between male students' age (mean = 22.75, SD = 4.11) and female students' age (mean = 21.23, SD = 3.28). The respondents were predominantly between 18 and 25 years of age. With regard to respondents' frequency for using university foodservice, about half of the respondents answered "more than two times a week" (47.4%).

Overall, respondents answered 51% of the objective nutrition questions correctly. Their level of nutrition confidence, how confident they were in their knowledge of nutrition, was just at the mid-point (mean = 3.49, SD = 0.75), indicating that they considered themselves somewhat knowledgeable about nutrition. There was no significant difference between male and female students' objective nutrition knowledge. To compare their objective knowledge and nutrition confidence, the points of objective knowledge were categorized in five segments based on the number of correct answers: (1 - 2 = not at all knowledgeable, 3 = not knowledgeable, 4 = neutral, 5 = knowledgeable, and 6 - 7 = very knowledgeable).

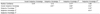

As shown in Table 1, there was significant correlation between objective nutrition knowledge and nutrition confidence. This study used a mean value of nutrition confidence as an indicator of overall nutrition confidence. The result of the correlation showed overall subjective knowledge had significant correlation with all three nutrition confidence items. In addition, nutrition confidence had a significant correlation with overall subjective knowledge. One item asked about the level of agreement with statement "I have more nutrition knowledge compared to my peers."

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with a maximum likelihood method was used to test the relationships among constructs, following the two-step approach in which the measurement model was first confirmed, and then the structural model was tested. The internal consistency and convergent validity of each construct were assessed. Cronbach's Alpha indicated adequate internal consistency of multiple indicators for each construct. Convergent validity was confirmed. All the standardized factor loadings on their underlying constructs; they were significant at 0.05 level and exceeded 0.5 except with four items in "perceived Barrier to eating healthy food." These validity and reliability test results suggested that the deletion of four items would improve positively the overall reliability of latent variables in perceived Barrier to eating healthy food.

Cronbach's coefficient alphas were again computed to obtain internal consistency estimates of reliability for the seven constructs. The results showed that all seven constructs met the minimum Cronbach's coefficient reliability of 0.70 (alphas between 0.88 and 0.98), which indicated satisfactory internal consistency of each construct. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was undertaken to assess the overall fit of the measurement model and to establish convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs. The "goodness-of-fit" of the measurement model, as suggested by the fit indices, did not fit the data well (Comparative Fit Index = 0.819, Normed Fit Index = 0.745, and Incremental Fit Index = 0.821). Therefore, based on the modification indices, a number of correlations between the errors of the variables of the same factor were added to the model. This modification did not violate the theoretical assumptions of the model because all correlations were within the same factor. After the modifications, the model had a reasonable fit to the data. The ratio of χ2 to degrees of freedom was 1.635 (P > 0.05). Given the known sensitivity of the χ2 statistics test to sample size, several widely used goodness-of-fit indices demonstrated that the confirmatory factor model fit the data well (NFI = 0.849, CFI = 0.934, IFI = 0.935, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation = 0.050).

The level of internal consistency of each construct was then assessed. The composite reliabilities of constructs ranged from 0.780 to 0.879 indicating adequate internal consistency of multiple indicators for each construct; the cutoff value of composite reliabilities should exceed 0.70. To assess convergent validity, all factor loadings on their underlying constructs were evaluated. As shown in Table 2, all the factor loadings for latent constructs were significant (P < 0.001) and high (exceeded 0.50), suggesting convergent validity (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Moreover, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of all constructs exceeded the minimum criterion of 0.419, indicating that a large portion of the variance was explained by the constructs. The AVEs were greater than the squared correlations between pair of constructs except of that between Susceptibility and Severity, suggesting discriminant validity. The seven-factor confirmatory measurement model demonstrated the soundness of its measurement properties. In summary, the assessment of the measurement model showed good evidence of reliability and validity for the operationalization of the latent constructs. Details of the properties of the measurements between study constructs are shown in Table 2.

The maximum likelihood estimation in AMOS 6.0 (IBM Corporation, Chicago, USA) was used in the current study. SEM is well-suited for this type of analyses because it allows researchers to test models consisting of multiple outcomes (e.g., Behavioral Intention to Eat Healthy Food and Behavioral Intention to Do Physical Activity) and allows for the inclusion of variables that have potentially high correlations, (e.g., Susceptibility, Severity, Benefit, and Barrier). This study was mainly designed to measure the impact of Health Beliefs on Behavioral Intention in two hypothesized ways: (a) via a direct relationship between Health Beliefs and Behavioral Intentions, and (b) via a direct relationship through nutrition confidence and Behavioral Intention. As specified in the analyses plan, multivariate analysis was conducted to test these proposed relationships.

Hypothesis 1 suggested objective knowledge has a direct, positive impact on college students' confidence in nutrition knowledge. As a result of testing Hypothesis 1, nutrition knowledge was found to have a significant relationship to participants' confidence in nutrition knowledge (r = 0.16, P < 0.05). Those who had a strong familiarity with nutrition concepts were aware of this knowledge and were comfortable using it. Those who had fewer correct answers in the nutrition knowledge section, may have guessed at answers on the survey, but were equally as aware of their knowledge and that lack of knowledge.

Hypothesis 2 proposed college students with confidence in their nutrition knowledge will have strong nutrition beliefs. While nutrition confidence was not significantly related in a positive way to their perceived Susceptibility (r = -0.06, P = 0.432) nor perceived Severity (r = 0.01, P = 0.844), nutrition confidence had significant relationships with Benefit (r = 0.35, P < 0.001) and Barrier (r = 0.28, P < 0.001). The Hypothesis 2a (H2a) was not supported by the path analysis. The results showed that college students' confidence in their nutrition knowledge was not associated with an accompanying concern about four types of diseases (Obesity, Diabetes, CVD, and Osteoporosis) outlined in the study. Hypothesis 2b (H2b) was also not supported, and Nutrition Confidence did not impact the level of worry about the severity of the diseases. However, Hypothesis 2c (H2c) was significantly supported. The results showed that those who had confidence in their Nutrition Knowledge were aware of the benefits of eating healthy food. In the same way, the results of this study proved the H2d by showing that respondents who had a high level of Nutrition Confidence, also recorded a higher level for the section related to the importance of Barrier to Eating Healthy Food than did other respondents. They apparently felt that healthy food was seasonally available and affordable. Hypothesis 2 was supported by the study participants who had strong nutrition confidence had strong nutrition beliefs.

Hypothesis 3 proposed relationships between Health Beliefs and Behavioral Intentions. Susceptibility did not have significant relationships with Behavioral Intention to Eat Healthy Food and/or Do Physical Activity. While Severity had a significant positive impact on Behavioral Intention to Eat Healthy Food (r = 0.08, P < 0.05), there was no significant correlation with doing Physical Activity. Benefit from healthy food consumption had a significant impact Behavioral Intention to Eat Healthy Food (r = 0.15, P < 0.05) and Behavioral Intention to Do Physical Activity (r = 0.28, P < 0.001). This study used the reversed score of Barrier, and Hypotheses 3g and 3f expected a positive relationship between Barrier and Behavioral Intentions. Path analysis found that reversed Barrier scores had a positive impact on Behavioral Intention to Eat Healthy Food (r = 0.20, P < 0.01) and Behavioral Intention to Do Physical Activity (r = 0.24, P < 0.001). Hypothesis 3a was not supported by path analysis. Results showed that there was no significant relationship between college students' Susceptibility and Behavioral Intention to eat healthy food. In the same way, the result of the Hypothesis 3b test showed college students' level of susceptibility did not have significant impact on Behavioral Intention to Do Physical Activity. Hypothesis 3c was supported by path analysis which showed that those who showed a high level of Severity of diseases were willing to eat healthy food. However, the result of H3d test showed that college students who had a high level of Severity did not intend to do exercise for their health. Path analysis for Hypothesis 3e showed a significant relationship between Benefits of eating healthy food and Behavioral Intention to eat healthy food. The result for Hypothesis 3f showed that the respondents who believed they would have benefits by eating healthy food were willing to eat healthy food. The Hypothesis 3g was supported by showing that those who had a low level of Barrier to Eat Healthy Food would eat healthy food. In a similar way to Hypothesis 3g, the result of analysis for H3h showed that college students who believe they have a low level of Barrier to eat healthy food, also showed a positive intention to be involved in physical activity. A summary of outcomes for hypotheses 1-3 is presented in Table 3.

A comparison of both the strength and pattern of Nutrition Confidence indicates that nutrition confidence seems to have a stronger impact on both Benefit and Barrier than do Susceptibility and Severity. Benefit is significantly related to higher Behavioral Intention for eating healthy food and doing physical activity, while Barrier is significantly related to a lower level of Behavioral Intentions. These findings support the proposition that Health Expectation, including Benefit and Barrier, is directly related to Behavioral Intentions for college students' healthy lifestyle. Higher levels of expectation were associated with healthier life style for college students. In other words, college students did not perceive a threat, including Susceptibility to and/or Severity of four types of disease (Obesity, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Osteoporosis). The results of testing the hypothesized model are shown in Fig. 1.

In summary, these results showed that a high level of Benefit and a low level of Barrier about eating health food will lead to positive Behavioral Intentions to eat healthy food and do physical activity. The findings are consistent with previous studies, the results of which showed that health-related classes have the potential to positively affect the attitudes and behaviors of college students [12]. Also, Kinzzie (2005) found that more knowledge about healthy food may incline people to a healthy diet. In addition, the previous research showed higher preventive Behavioral Intentions for an elderly group [13]. One possible explanation is that chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis, are not common among young age groups. College students may already understand how to prevent those diseases, and may not experience any threat from those diseases. Another possibility is that Behavioral Intentions may function partly as a way for respondents to cope with the worry they experienced or observed from their family members, rather than as a straight measure of actual plans to do something.

The results validate that objective nutrition knowledge was a good predictor of college students' nutrition confidence. The results also clearly showed that, as hypothesized, two direct measures were significant predictors of Behavioral Intentions. Both perceived Benefit and Barrier had a significant effect on Behavioral Intentions and were a valid measurement to use to determine Behavioral Intentions. Additionally, it was determined that Susceptibility and Severity were not significant predictors of Behavioral Intentions for college students. Finally, this study helped to validate the use of the Health Belief Model in university foodservice and health-related marketplace.

The results of the current study provide empirical evidence of college students' health behaviors showing that nutrition knowledge leads to an increase in nutrition confidence; that nutrition confidence also influences Health Beliefs; and that positive Health Beliefs lead to an increase in Behavioral Intention to Eat Healthy Food and do Physical Activity.

The current findings support the hypothesis that perceptions of high Benefit and low Barrier regarding healthy diet will influence to Behavioral Intentions. The findings are consistent with research showing that university-sponsored physical activity and health classes have the potential to positively affect the attitudes and behaviors of the students [12]. Also, knowledge about healthy food may incline people to a healthy diet. Although this study proposed that Susceptibility and Severity may have an effect on college students' Behavioral Intention, this study did not find a significant result within this population of college students.

The younger generation seems to have more interest in, and knowledge of, nutrition. They apparently believe that better nutrition is a benefit to them. However, as is typical for most people, translating belief into action is not an easy thing to do. The previous study showed higher preventive Behavioral Intentions for an elderly group [14]. One possible explanation is that chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis, are not common among young age groups. College students may already understand how to prevent those diseases, and may not have any threat from those diseases. It is possible that Susceptibility and Severity may be more relevant to a more complex or unfamiliar preventative behavior. Another possibility is that intention may function partly as a way for respondents to cope with the worry they experience, rather than as a straight measure of actual plans to do something. The previous study suggested that intention did predict actual behavior, but did not account for 100% of the variance, leaving open the possibility that some part of the intention measure does reflect coping [15].

In addition, it would be worth examining how the relationship between expectations might impact to health behaviors. Behavioral intentions-including eating healthy food and engaging in physical activity-are simple and easy-to-do behaviors to measure, with a clear purpose and outcome. Behaviors that have a range of consequences, such as smoking, drinking alcohol, and sexual behavior, might not be as affected by an expectation, because the relationship between Health Beliefs and a Behavioral Intention may not seem as clear as the relationship between Benefit and Behavioral Intention to Eat Healthy Food or to Do Physical Activity. Also, behaviors such as eating healthy food and doing exercise are not chronic diseases but rather daily behaviors. Susceptibility to and Severity of diseases are not daily events for college students. In this study, college students might be more likely to influence a behavior that impacts daily decisions, and may be less likely to engage in behaviors that may or may not affect long term health issues.

The current study provided useful information for university foodservice managers to assess college students' eating behavior. The Health Belief Model applied to university foodservice is another approach to determining whether or not college students' health beliefs lead to appropriate food choices. According to the HBM, participation in healthy behaviors is influenced by beliefs about the likelihood of an action resulting in a perceived Benefit. The positive value of the Benefit must exceed the perceived Barriers or "cost of, and/or resistance to, the action." It is important for foodservice managers to encourage healthy food choices and reduce Barriers to enable students to act on their health beliefs.

In the U.S., the perception of Susceptibility to chronic diseases among adolescents may be very low; therefore, the advantage of health-promoting behaviors would be decreased. This population is generally healthy, and the threat of chronic disease is not apparent to them. Moreover, better understanding of the needs of college students is critical in order to improve university foodservice menus and the nutrition quality of the items on those menus, the availability of which can influence students' food choice decision. However, the number of healthy food options for students on campuses is a problem. Because of packaging issues and/or supply-chain difficulties in acquiring/serving fruits and vegetables, university foodservices have limited healthy options for food preparation on campus. There are few affordable fresh vegetables and fruits for students to choose. There may be packaged salads served on campuses, and these may be the best fresh vegetable options on campus, but eating salad is not common among male students, and salad dressing may contain a great deal of sugar and/or fat. In addition, students are often forced to grab food in while rushing between classes. Despite some of the healthier changes or trends on the college students' life styles, management of university foodservices still has a lot of work to do to provide healthy food options and reduce greasy and fried, fatty foods on campus. Until then, students who want to eat healthy food will have to continue to "brown bag it." The managers of university foodservices need to make firm commitments to provide healthier and more sustainable food options.

Although the results of this study suggested that Health Beliefs had a significant effect on the Behavioral Intention to Eat Healthy Food and do physical activity, these results should be viewed with limited generalizability, because all participants lived in the Southwestern region of the United States. Therefore, these results may not be representative of all college students. These findings need to be validated by applying the model to other consumer groups and other circumstances. In addition, the participants were volunteers; therefore, this group may have been more motivated or interested in learning about healthy food than those who did not participate in the survey. Further research with other college students throughout the country is needed to confirm the findings. There are many of studies regarding knowledge about healthy food and nutrition, especially, the impact of nutrition knowledge and beliefs on a healthy diet. Researchers have shown a positive correlation between health knowledge and improved dietary habits [16,17]. The understanding of the possible connections between diet and disease, the benefits of a healthy diet, and knowledge of nutrition can influence health behavior.

Unfortunately, the current study was unsuccessful in finding a relationship between Threats and Behavioral Intention. Susceptibility and Severity did not show significant relationship with Behavioral Intentions. In fact, the effect on Behavioral Intentions seemed to be mainly due to Benefit and Barrier. Despite the lack of support for the hypothesis, the study was successful in identifying empirical expectation about healthy food. A possible research direction based on the impact of threats to health would be to explore the effect of manipulating different levels of Susceptibility and Severity. The current study only researched the level of Susceptibility to and Severity of four types of disease. Higher levels of worry may lead to greater Behavioral Intentions and may have a stronger effect on actual health behavior. Therefore, it is likely that higher levels of worry would result in higher rates of self-protective behavior.

Additional research could also test possible moderators and mediators to the relationship of Health Beliefs and Behavioral Intentions. Work in the area of Fear Appeals suggests several possible variables that may moderate or mediate the worry-behavior relationship. Perceived efficacy, danger, and fear-control processes, and cognitive mediators such as perceived Susceptibility and perceived Severity have been shown to impact the effectiveness of Fear Appeals, and may moderate or mediate the relationship between health worry and health behavior.

Finally it is important to explore whether measuring current Health Beliefs would impact different health behaviors. Eating healthy food and doing physical activity-the key components of this study-are easy and highly controllable behaviors. Further research is needed on the Susceptibility and Severity of illness and whether or not fear of disease and/or the threat of disease along with more complex prevention strategies might lead to confusion or frustration rather than to intention to take action.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Results of Testing the Hypothesized Model *P < 0.05 **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.001, Dotted lines indicate non-significant structural paths, Overall Goodness-of-Fit Comparisons for the specified Model

GFI = Goodness of fit index, CFI = Comparative fit index, NFI = Normed fit index, IFI = Incremental fit index, TLI = Tucker-Lewis coefficient index, RMSEA = Root mean square error of approximation

References

1. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2000. JAMA. 2002. 288:1723–1727.

2. Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. JAMA. 2004. 291:2847–2850.

3. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, McDowell MA, Flegal KM. Obesity Among Adults in the United States--No Statistically Significant Change Since 2003-2004. NCHS Data Brief No 1. 2007. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

4. Kisch J, Leino EV, Silverman MM. Aspects of suicidal behavior, depression, and treatment in college students: results from the spring 2000 national college health assessment survey. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005. 35:3–13.

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. 2001. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General.

6. Freisling H, Haas K, Elmadfa I. Mass media nutrition information sources and associations with fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2010. 13:269–275.

7. Kim HS, Lee SM, Yuan JJ. Assessing college students' satisfaction with university foodservice. J Foodservice Busi Res. 2012. 15:39–48.

8. Joung HW, Kim HS, Choi EK, Kang HO, Goh BK. University foodservice in South Korea: A study of comparison between university-operated restaurant and external foodservice contractors. J Foodservice Busi Res. 2011. 14:405–413.

9. Joung HW, Kim HS, Yuan JJ, Huffman L. Service quality, satisfaction, and behavioral intention in home delivered meals program. Nutr Res Pract. 2011. 5:163–168.

10. Becker MH. The Health Belief Model and Personal Health Behavior. 1974. Thorofare, NJ: Charles B. Slack, Inc..

11. Wildt AR, Ahtola OT. Analysis of Covariance. 1978. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

12. Cardinal BJ, Jacques KM, Levy SS. Evaluation of a university course aimed at promoting exercise behavior. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2002. 42:113–119.

13. Kinzie MB. Instructional design strategies for health behavior change. Patient Educ Couns. 2005. 56:3–15.

14. Wilcox S, Stefanick ML. Knowledge and perceived risk of major diseases in middle-aged and older women. Health Psychol. 1999. 18:346–353.

15. Prentice RL, Willett WC, Greenwald P, Alberts D, Bernstein L, Boyd NF, Byers T, Clinton SK, Fraser G, Freedman L, Hunter D, Kipnis V, Kolonel LN, Kristal BS, Kristal A, Lampe JW, McTiernan A, Milner J, Patterson RE, Potter JD, Riboli E, Schatzkin A, Yates A, Yetley E. Nutrition and physical activity and chronic disease prevention: research strategies and recommendations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004. 96:1276–1287.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download