Abstract

This pilot study was performed to produce data of the Children's Dietary Life Safety (CDLS) Index which is required by the Special Act on Safety Management of Children's Dietary Life and to evaluate the CDLS Index for 7 metropolitan cities and 9 provinces in Korea. To calculate the CDLS Index score, data regarding the evaluation indicators in the children's food safety domain and children's nutrition safety domain were collected from the local governments in 2009. For data regarding the indicators in the children's perception & practice domain, a survey was conducted on 2,400 5th grade children selected by stratified sampling in 16 local areas. Relative scores of indicators in each domain were calculated using the data provided by local governments and the survey, the weights are applied on relative scores, and then the CDLS Index scores of local governments were produced by adding scores of the 3 domains. The national average scores of the food safety domain, the nutrition safety domain and the perception and practice domain were 23.74 (14.67-26.50 on a 40-point scale), 16.65 (12.25-19.60 on a 40-point scale), and 14.88 (14.16-15.30 on a 20-point scale), respectively. The national average score of the CDLS Index which was produced by adding the scores of the three domains was 55.27 ranging 46.44-58.94 among local governments. The CDLS Index scores produced in this study may provide the motivation for comparing relative accomplishment and for actively achieving the goals through establishment of the target value by local governments. Also, it can be used as useful data for the establishment and improvement of children's dietary life safety policy at the national level.

Dietary life safety is a very important subject to everyone. It is necessary for home, school, and the nation to be actively involved in the effort and support towards ensuring safety when considering that children have difficulty in judging the problems of dietary life by themselves as well as actively handle the problems [1]. The proper dietary habit of children leads to healthy adulthood, and can reduce the incidence of major chronic diseases in their old age and the expense for treatment; thus it is very important for the financial aspect of national health care to reduce risk in dietary life safety and health with regards to children [1,2].

In the past, the major nutritional problem was nutrition insufficiency or deficiency because economic difficulties were the obstacle to safe dietary life, but recently, overnutrition, nutrition imbalance, and undernutrition coexist and nutritional inequality is deepening in both advanced countries and developing countries [3]. Because the polarization due to income disparity by household, by region, and by country brings about issues of disparities in health and food access such as food insecurity, efforts should be made at the national and local community levels to actively solve the problems of dietary life safety [4].

The dietary life environment can bring about the increase of obesity and chronic diseases beyond personal factors such as knowledge, skills, and motivation. The intervention of the dietary life environment and policy can be the most effective strategy in the improvement of dietary life [5].

The Special Act on Safety Management of Children's Dietary Life, which was established in March of 2008, has provided the legal basis for ensuring the children's dietary life safety. According to this Act, the director of the Korea Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) should regularly investigate and announce the Children's Dietary Life Safety (CDLS) Index to objectively confirm and evaluate the children's food safety and nutrition levels [23]. Evaluation indicators were developed to draw the CDLS Index under the support of KFDA in 2009 in accordance with the enforcement of the law. The evaluation indicators for drawing the CDLS Index are divided into three domains which are 'children's food safety', 'children's nutrition safety', and 'children's perception and practice' [1].

The 'children's food safety' domain evaluates efforts for children's safety from food poisoning or harmful environments in the aspect of food sanitation and for reducing the possibility of continuous exposure to high-calorie foods with low nutritional value or unsanitary foods [6]. The 'children's nutrition safety' domain includes efforts for ensuring nutrition adequacy and balance, and the 'children's perception and practice' domain includes indicators related to the individual's perception, attitude, and choice for dietary life safety [7].

According to the Special Act [24], local governments such as city, 'gun' (county), or 'gu' (borough) should investigate and evaluate the food safety and nutrition levels using the CDLS Index, and the results should be announced. Then, KFDA Commissioner, mayors of metropolitan cities, governors of provinces, mayors of 'gun' and 'gu' local governments and chief education officers of cities and provinces should provide education and promote the safety of children's favorite foods and nutrient supply depending on individual or group characteristics, health status and health perception levels [13].

Studies on the production and evaluation of the CDLS Index and its policy trend are seldom reported in foreign cases. However, when it comes to each domain of dietary life safety, various programs for safety management by the central or local governments have been performed or progressed. Various efforts for prevention of food poisoning due to school foodservice have been made at the institutional and personal hygiene levels in many countries including the USA [8], and the efforts for improving the environment for food safety have been developed in schools and the surrounding areas [9]. In the nutrition domain, many studies have been performed for prevention of childhood obesity [10] and nutrition imbalance [11,12]. A strategic plan has been developed to promote more healthful eating behaviors and lifestyles [13]. Also, various programs have been implemented at the national and local community levels in relation to the modification of individual dietary behaviors because dietary life safety is influenced by the individual's perception and practice level [14].

There has been, however, no case reported on the evaluation of effort for children's dietary life safety at the national or local government level, as in this study. Thus, this pilot study was performed to produce CDLS Index scores and to evaluate the levels of children's dietary life safety management by local governments using the CDLS Index measures.

The development process of evaluation indicators for the CDLS Index has been already described in detail in the previous report [1]. In short, evaluation indicator candidates were selected by reflecting the content of the Special Act on Safety Management of Children's Dietary Life and risk factors in children's dietary life safety from domestic and foreign research articles, national statistics, Health Plan 2010 [15], the dietary guidelines for infants, children, and adolescents [16], Korea Nutrition and Health Examination Survey (KNHANES) data [17], and the Korean Food Guide of the KDRIs [18]. The CDLS Index evaluation indicators were selected through the consultation of various groups including nutritionists, field experts, and persons in charge of administration and policy of dietary life safety. For selected evaluation indicators, the weights were primarily obtained by conducting the AHP (analytic hierarchy process) survey on professionals and then finally determined through the Delphi survey, which is described in detail in ref. [1].

Data on evaluation indicators were collected from local governments in cooperation with the KFDA's Dietary Life Safety Division.

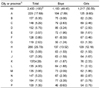

The subjects were selected from 5th grade Korean students by using stratified sampling. Table 1 shows the distribution of children among 16 local governments. The overall sample size was 2,400, and the percentages of male and female subjects were 49.45% and 50.55%, respectively.

The nationwide survey for children's dietary life safety perception and practice level was conducted in 7 metropolitan cities and 9 provinces between June 22 and July 10, 2009 in collaboration with Gallup Korea under the cooperation of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology as previously reported [19].

Relative scores of evaluation indicators were drawn from data collected by local governments according to the scale of each evaluation indicator, and then weighted scores were calculated by applying the weight to the relative score.

Calculation of relative scores by evaluation indicators of the CDLS Index are shown in Table 2. For the relative score for the 'obesity proportion' indicator, the reference of the evaluation scale was the obesity proportion of 13 to 18 year-old adolescent boys. The obesity proportion of 7 to 12 year-old children was low being around 5~8%, while that of 13 to 18 year-old adolescents, particularly male adolescents, was over 20%, according to referred data [20]. The score of 100 was given, when the proportion of obesity was less than 5%, the score of 60 was given, when the proportion of obesity was more than 25%, and a score between 60 and 100 was assigned proportionally to the proportion of obesity at 5~25%. The 'establishment of school food-service support ordinance by local government' was 100 points when all 'gu' or 'gun' local governments in the corresponding metropolitan city or province established the ordinance and 0 points when none of them established it.

The score of the CDLS Index of each local government was produced by adding the scores of three domains. Since this pilot project was carried out to evaluate and review the CDLS Index through the testing performance of local governments, 16 local governments were designated with alphabets from A to P.

The basic statistical analysis of perception and practice level data was performed using SAS 9.01 (Cary, USA) and the percentage (%) was obtained by the frequency method. Bonferroni's multiple T-test was applied using a statistical program SUDAAN, for significance testing by relative scores among local governments.

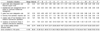

The results after applying weight to the relative score by each evaluation indicator of the 'children's food safety' domain are shown in Table 3. Among the 'children's food safety' evaluation indicators, the score of 'establishment and management level of center for child-care foodservice management' was the lowest and all local governments had a score of 0 points at the time of the survey in 2009. The next lowest one was 'good retail store designation and financial support level' and the national average was 0.23 out of 5 points. The national average of the 'green food zone designation rate' indicator was 5.03 out of 6 points, and 'A', 'E', 'F', 'G', 'I' and 'L' local areas achieved perfect scores designating all school neighborhoods as a green food zone, while 'P' and 'N' local areas received only 1.99 and 2.45 points, respectively. The national average of the 'honorary food sanitation inspector rate' was 2.09 out of 3 points, 'A' local area achieved full marks of 3 points, while 12 local governments achieved less than 1 point. The national average of the 'violation rate of the Food Sanitation Act in children's food-service operations' was 7.87 out of 8 points, and 'P' local area achieved 8 points. The national average of the 'incidence of food-borne illness in children's food-service operations' was 8.51 out of 11 points. 'J', 'L', 'M', 'O' and 'P' local areas gained full marks, 'C' got 6.00, and 'G' obtained 0 points.

A perfect score for the 'children's food safety' domain is 40 points. 'F' local area gained the highest score with 26.50 points and 'G' local area obtained the lowest with 14.67 points. The national average score of the 'children's food safety' domain was 23.74 points, which was equivalent to 59.35 out of 100 points.

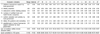

The results after applying weight to the relative score by each indicator of the 'children's nutrition safety' domain are shown in Table 4.

The maximum weighted score of the 'children's food-service support rate by local government' indicator was 7 points, and the national average was 3.50 points. 'A' local area achieved 5.26 points, 'O' had 4.01 points, and 'E' local area received the lowest as 2.23 points. The maximum score for 'obesity proportion' was 6 points, but the same relative score, 4.54 points, was applied to all local governments because data on the obesity proportion of local governments was not produced. The score range of the 'restaurant's nutrition labeling practice rate' indicator was only 0.00~0.01 points in spite of the maximum being 3 points. The 'numbers of certified foods and health-friendly companies' was first surveyed in 2009 and the information on those numbers by local governments was not present. Therefore, this indicator was calculated as a national indicator, and the relative score was given on the basis of the target value of the year concerned. All local governments received 1.0 point.

The score of 'nutrition education and publicity by local government' was based on two evaluation scales, that is, the ratio of target subjects who received annual nutrition education and the number of public health center dietitians employed by local government, which were summed to 100 points, to which the weight was applied to make the maximum 6 points. As a result, the national average was 0.96 points and the highest score was achieved by 'P' local area (2.09). The national average score of 'dietary life guidance and counseling' was 2.52 points and 'B' local area achieved the highest as 4.20 points as compared with 'K' (1.08), 'N' (1.41), and 'O' (1.10) (P < 0.05). The national average of the 'establishment of school food-service support ordinance by local government' was 3.87 out of 5 points, and 'C' local government obtained the lowest score, 0.63. Seven out of 16 local governments received perfect scores.

The full mark of indicators in the 'children's nutrition safety' domain is 40 points. Among 16 local governments, 'I' local area achieved the highest score as 19.60 points and 'C' local area obtained the lowest score as 12.25 points. The national average of 'children's nutrition safety domain' was 16.65 points, which was equivalent to 41.62 out of 100 points and seems very low and is significantly lower than that in the food safety domain.

The results after applying weight to the relative score by each indicator of the 'children's perception and practice' domain are shown in Table 5. The indicators showing statistically significant differences among local governments were 'personal hygiene management perception and practice level', 'three meals eating level', and 'fruit, vegetable, and white milk eating level'.

The highest national average was 3.70 points for 'three meals eating level' and the lowest one was 0.55 points for 'perception and practice of high calorie foods with low nutritional value'. For 'personal hygiene management perception and practice level', 'I' local area gained the highest scores with 3.56 points and 'P' received the lowest scores with 3.07 points. The score of 'three meals eating level' was higher in 'K' (3.82), 'B' (3.80), and 'N' (3.77) local areas compared to 'P' (3.55), and that of 'fruit, vegetable, and white milk eating level' was the highest in 'N' as 2.04 points compared to 'D' (1.84), 'E' (1.82), 'F' (1.83), and 'L' (1.80) (P < 0.05).

The national average of the total score of the 'children's perception and practice level' domain was 14.88 out of 20 points, which was equivalent to 74.41 out of 100 points, and the scores of the perception and practice level could be evaluated as the highest as compared to those of the 'food safety' domain and the 'nutrition safety' domain. For local governments, 'N' obtained the highest score, 15.30 and 'P' received the lowest score, 14.16 points.

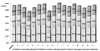

The scores of the CDLS Index by local government are presented in Fig. 1. The national average score was 55.27 points. Among local governments, 'I' achieved the highest score with 58.94 points, and 'L' had the second highest score with 57.77. 'C' and 'G' local areas obtained low scores with 46.44 and 47.04, respectively. None of the 16 local governments demonstrated a score over 60 points. The average CDLS Index score of the 7 metropolitan cities was 52.68 and that of the 9 provinces was 55.25, and the difference was not statistically significant. Among the three domains, the score of the 'children's nutrition safety' domain was significantly different between metropolitan cities (15.65 ± 1.68) and provinces (17.25 ± 1.25) at P < 0.05.

Recently, environmental and policy interventions have been suggested as the most effective strategies for creating population-wide improvements in eating, although individual behaviors such as food sanitation practices, healthy food choices, and food habits are important determinants of safe dietary life. Familial factors and the nature of foods available in the physical environment, including at home, schools, and fast-food establishments, are significant determinants which influence healthy eating in children and youth [21].

The CDLS Index in this study not only cross-sectionally evaluates the efforts and the outcomes of children's dietary life safety among local governments, but also longitudinally evaluates it by periodically measuring the changes during 3 years according to Article 15 of the Enforcement Ordinance on the Special Act on Safety Management of Children's Dietary Life [23]. This kind of index has never been reported domestically or overseas, thus there are few comparisons with regards to previous outcomes. Evaluation indicators used to derive CDLS Index scores are composed of three domains: food safety, nutrition safety and perception and practice. Each indicator and its scale should be validated and modified through the application to performance measures of local governments.

Among 6 'children's food safety' evaluation indicators, the 'establishment and management level of center for child-care foodservice management' (7-point scale) was 0 because the center for child-care foodservice management was not established in all local governments at the time of survey in 2009. The center for child-care foodservice management, which supports the sanitation and nutrition management for food service facilities such as daycare centers and kindergartens [22,23], should be established and managed by the head of the local government. Three locations were test-operated in 2010 and 12 locations in 2011, 22 locations in 2012, and a plan of establishment of 70 centers nationwide by 2015 was announced by KFDA (KFDA press release, 2012.2.24). Therefore, it is expected as an indicator which will contribute to the improvement of the CDLS Index score through the effort of local governments in the near future.

The 'good retail store designation and financial support level' (5-point scale) also showed very low scores of 0~0.56 points. The good retail store designation has been disregarded because there was no financial support or benefits from the government when designated as the good retail store and unprofitable business activities due to the limitation of sales items. Thus, an action plan to promote the designation of good retail stores is required at both the national and local level.

Generally, the indicators that greatly affected the overall score in the 'children's food safety' domain were the violation rates of the Food Sanitation Act in children's food-service operations and the incidence of food-borne illness in children's food-service operations with 8 and 11 points, respectively, out of 40 points (47.5%). The reason for the higher score of the 'children's food safety' domain compared to the nutrition safety domain was considered to be due to the two indicators related to sanitation as they were greatly influential and the sanitation-related safety management was relatively good. Nevertheless, further efforts to improve the quality problems associated with food sanitation are necessary, because school food-service has been responsible for the 2/3 of the food poisoning cases in the country [24]. With that in mind, efforts for preventing the outbreak of food poisoning in food-service facilities have been made in other countries. In the USA, the safety of the school food-service program has been improved through the followings: first, the requirement of food-service workers with training and certification in food safety operation; second, the use of food safety procedures on the basis of hazard factors; third, the purchase of pre-cooked meats and poultry to reduce hazard factors of food-poisoning pathogens; finally, the requirements of strict food supply by USDA when purchasing foods for schools [25].

Individual behaviors to make healthy choices can only occur in a supportive environment with accessible and affordable healthy food choices [5]. Among 7 evaluation indicators in the 'children's nutrition safety' domain, the obesity rate in children and adolescents has been rapidly increased with the rapid changes and westernization of our lifestyle [26]. Six departments including the Ministry of Health and Welfare are in charge of a total of 25 obesity-related laws and regulations including the National Health Promotion Act, Special Act on Safety Management of Children's Dietary Life, and School Meals Act. It has been considerably pointed out that the connectivity of projects and the synergistic effect were reduced because several institutions independently promoted the project [27].

Even in the advanced economic environment and social security system of America, it has been reported that the lack of food intake in the low-income group is serious due to food insecurity [4]. It was also reported in a study on Korean children that the nutrient intake was low in groups with higher food insecurity [28]. Reflecting these results, the 'children's food-service support level by local government' was selected as an indicator of nutrition safety. However, the children's food-service budget varies depending on the financial independence of the local government. Thus, it is necessary to modify and revise this indicator reflecting the financial situation, but in reality, its modification is difficult.

The 'restaurant's nutrition labeling practice' was divided into a national indicator and a local government indicator: the number of target restaurants practicing nutrition labeling for obligatory nutrition labeling was evaluated as the national indicator and the number of restaurants voluntarily practicing nutrition labeling among restaurants in the local area was evaluated as the local governments' indicator. A restaurant chain with 100 or more locations have been required to practice nutrition labeling since 2010. The nutrition labeling practice level of local restaurants was very low, which is considered to be due to a lack of promotional publicity for restaurant's nutrition labeling by local government because it was test-operated in 2009. Therefore, the scores regarding nutrition labeling practice of local restaurants can be considerably improved depending on the effort of each local government.

The scores for the 'numbers of certified foods and health-friendly companies' were identically applied to all local governments because there was no certified or designated cases by local government in 2009. Such indicators will be gradually improved through the annual survey for the CDLS Index because the initial score of local governments was zero. The evaluation indicator with the highest weight among the 'children's nutrition safety' domain was 'dietary life guidance and counseling' with the full marks of 11 points, and the range of 16 local governments was 1.08-4.20 points, showing a relatively large difference in performance by local governments. For the 'nutrition education and publicity by local government', it was pointed out that the establishment of accurate criteria for the number of target subjects for education and publicity and the number of promotion cases was difficult.

Evaluation indicators in the 'children's perception and practice' domain included a total of 7 indicators. One is the 'perception for high calorie foods with low nutritional value', the concept of which is similar to the foods of minimal nutritional value (FMNV) in the school food-service program of the USA. Efforts for the development of various labeling methods or for establishing a safe food environment have been actively progressed for children, who often lack the understanding for foods, to choose healthy foods instead of unhealthy ones in the rapidly changing dietary life environment [29].

In the 2009 KNHANES data [17], the utilization ratio of nutrition labeling in the purchase of processed foods in children and adolescents was only 13.6% in 6 to 11 year-olds and 25.1% in 12 to 18 year-olds who responded to read the nutrition labeling. Thus, this indicator may contribute to efforts to focus on nutrition labeling education by local governments.

'Eating three meals a day' is very important for the variety of food intake, the quality of meals, and nutrition satisfaction. It has been reported that skipping breakfast is particularly related to obesity [30,31]. According to 2007~2009 the 4th KNHANES results, the rate of skipping breakfast was 9.8% for children [17]. Recent studies reported that increased intake of fast food and soft drinks reduced the intakes of fruits, vegetables, and milk [32-34]. These behaviors are associated with the higher risk of obesity. Therefore, not only decreasing the intake of fast food and soft drinks but also increasing the intake of vegetables and fruits are considered to be important to promote children's perception and practice level in regards to obesity management. Similar items are included in the Youth Healthy Eating Index (YHEI) [35]. Kim et al. [36] recently published that meal skipping was related to poor food choice, low perception of nutrition labeling and a high prevalence of obesity, using the data on perception and practice level obtained through this study.

A policy to promote active consumption of healthy foods is needed along with the prohibition on advertisement and sales of unhealthy foods. The USDA Fresh Fruit/Vegetable Program, Australia's Cool CAP (canteen accreditation program), and healthy eating in school programs in Singapore such as the fresh fruit vending machines program are examples of such a policy.

Through the calculation and evaluation of the CDLS Index, local governments can establish policies for solving the items neglected or problems among factors that affect dietary life safety, and examine the safety management measures by reviewing the problems observed in both the safety domain and items. Also, as clearly stated in the Special Act on Safety Management of Children's Dietary Life, the production and evaluation of the CDLS Index should be conducted by local government every year to compare the relative achievement of each indicator of the CDLS Index and to designate the goal of the CDLS Index by local government, which can motivate more positive efforts for achieving the goals. It can be used as a ground data for establishment, and modification and improvement of children's dietary life safety policy by evaluating the effect of children's dietary life safety management at the national level.

Some of the evaluation indicators used in this study have limitations on the feasibility of data collection, because it is impossible to secure data of local governments for the present, despite the importance as indicators of children's dietary life safety. To produce more reliable data for the CDLS Index, strategies for collecting data and cooperation with local governments are very important as well.

In the present study, the CDLS Index scores of all local governments are below 60 points, which means there is enough room for the progress of scores in the future. Nevertheless, it is necessary to make an effort for the improvements of the CDLS Index through consideration of the limits revealed in the fields, as shown by measures of several indicators which are discussed already. Lastly, evaluation indicators and performance measures for the CDLS Index should be reviewed periodically, modified, and revised to reflect dietary and lifestyle changes and environments as well as the nation's food and nutrition policies.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1

Total scores of the Children's Dietary Life Safety Index by local governments *A~G: metropolitan cites, H~P: provinces |

References

1. Chung HR, Kwak TK, Choi YS, Kim HY, Lee JS, Choi JH, Yi NY, Kwon S, Choi YJ, Lee SK, Kang MH. Development of evaluation indicators for a children's dietary life safety index in Korea. Korean J Nutr. 2011. 44:49–60.

2. Nicklas T, Johnson R. American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: dietary guidance for healthy children ages 2 to 11 years. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004. 104:660–677.

3. Doak CM, Adair LS, Bentley M, Monteiro C, Popkin BM. The dual burden household and the nutrition transition paradox. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005. 29:129–136.

4. Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010. 140:304–310.

5. Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008. 29:253–272.

6. Cho SD, Lee SJ, Yun JH, Kim SY, Lee EJ, Park HK, Kim MC, Chung KH, Kim GH. Development of certification mark of food quality for children's favorite foods safety management. J Food Hyg Saf. 2008. 23:31–39.

7. Cho SH, Yu HH. Nutrition knowledge, dietary attitudes, dietary habits and awareness of food-nutrition labelling by girl's high school students. Korean J Community Nutr. 2007. 12:519–533.

8. U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). School Meal Programs, Few Instances of Foodborne Outbreaks Reported, but Opportunities Exist to Enhance Outbreak Data and Food Safety Practices (GAO-03-530). 2003. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Accountability Office.

9. Guidance for school food authorities: developing a school food safety program based on the process approach to HACCP principles. United States Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service [Internet]. 2005. Available from: http://www.fns.usda.gov/fns/safety/pdf/HACCPGuidance.pdf.

10. Davis MM, Gance-Cleveland B, Hassink S, Johnson R, Paradis G, Resnicow K. Recommendations for prevention of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2007. 120:Suppl 4. S229–S253.

11. Frary CD, Johnson RK, Wang MQ. Children and adolescents' choices of foods and beverages high in added sugars are associated with intakes of key nutrients and food groups. J Adolesc Health. 2004. 34:56–63.

12. O'Toole TP, Anderson S, Miller C, Guthrie J. Nutrition services and foods and beverages available at school: results from the school health policies and programs study 2006. J Sch Health. 2007. 77:500–521.

13. U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). USDA Strategic Plan for FY 2005-2010. 2006. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

14. Turconi G, Guarcello M, Maccarini L, Cignoli F, Setti S, Bazzano R, Roggi C. Eating habits and behaviors, physical activity, nutritional and food safety knowledge and beliefs in an adolescent Italian population. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008. 27:31–43.

15. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Health Plan (2006-2010): 2008 Action Program. 2009. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare.

16. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Dietary Guidelines: Infants, Children and Adolescents. 2009. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare.

17. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Report on National Health Statistic 2009. 2010. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare.

18. The Korean Nutrition Society. Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans. 2010. Seoul: The Korean Nutrition Society.

19. Lee JS, Kim HY, Choi YS, Kwak TK, Chung HR, Kwon S, Choi YJ, Lee SK, Kang MH. Comparison of perception and practice levels of dietary life in elementary school children according to gender and obesity status. Korean J Nutr. 2011. 44:527–536.

20. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Report on National Health Statistic 2007. 2009. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare.

21. Taylor JP, Evers S, McKenna M. Determinants of healthy eating in children and youth. Can J Public Health. 2005. 96:Suppl 3. S20–S26. S22–S29.

22. Lee MS, Lee JY, Yoon SH. Assessment of foodservice management performance at child care centers. Korean J Community Nutr. 2006. 11:229–239.

23. Kim SY, Yang IS, Yo BS, Back SH, Shin SY, Lee HY, Park MK, Kim YS. Assessment of the foodservice management practices in child care centers and kindergartens. Korean J Food Nutr. 2011. 24:639–648.

24. Ha SD. Management policy and safety problem of school food services. Safe Food. 2008. 3:13–21.

25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Division of Adolescent and School Health. Research Application Branch. Train-the-trainer manual for school foodservice personnel, 2007 [Internet]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/foodsafety/pdf/fssag_train_07.pdf.

26. Son JE, Ku HJ, Lee J, Lee MC, Lee DT. Changes of physique, physical fitness, and obesity indices in Korean adolescents: from 1956 to 2004. Korean J Health Promot Dis Prev. 2006. 6:213–221.

27. Kwak NS, Kim E, Kim HR. Current status and improvements of obesity related legislation. Korean J Nutr. 2010. 43:413–423.

28. Oh SY, Kim MY, Hong MJ, Chung HR. Food security and children's nutritional status of the households supported the national basic livelihood security system. Korean J Nutr. 2002. 35:650–657.

29. Choi YS, Chang N, Joung H, Cho SH, Park HK. A study on the guideline amounts of sugar, sodium and fats in processed foods met to children's taste. Korean J Nutr. 2008. 41:561–572.

30. Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM, Carson T. Trends in breakfast consumption for children in the United States from 1965-1991. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998. 67:748S–756S.

31. Song WO, Chun OK, Kerver J, Cho S, Chung CE, Chung SJ. Ready-to-eat breakfast cereal consumption enhances milk and calcium intake in the US population. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006. 106:1783–1789.

32. Collison KS, Zaidi MZ, Subhani SN, Al-Rubeaan K, Shoukri M, Al-Mohanna FA. Sugar-sweetened carbonated beverage consumption correlates with BMI, waist circumference, and poor dietary choices in school children. BMC Public Health. 2010. 10:234–247.

33. Nickelson J, Roseman MG, Forthofer MS. Associations between parental limits, school vending machine purchases, and soft drink consumption among Kentucky middle school students. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010. 42:115–122.

34. Sebastian RS, Wilkinson Enns C, Goldman JD. US adolescents and MyPyramid: associations between fast-food consumption and lower likelihood of meeting recommendations. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009. 109:226–235.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download