Abstract

Figures and Tables

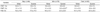

Table 4

HB: Health beverage, SB: Sweetened beverage, CD: Carbonated drink, FD: Functional drink.

All values are mean ± SD.

1)Consumed beverages were separately classified as "health beverage" and "sweetened beverage" based on their potential roles in the health and prevention of obesity in children. Health beverage included milk and soybean milk.

2)Sweetened beverage was defined as all beverages consumed except milk and soybean milk.

3)Milk: included any type of cows' milk

4)Juice: 100% fruit juice, fruit-flavored drinks, and drinks that contained fruit juice in part were combined

5)Sports drinks, diet drinks, traditional drinks and other functional drinks were combined

6)Significantly higher than the juice consumption of boys in summer at P < 0.05

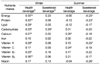

Table 5

HB: Health beverage, SB: Sweetened beverage, CD: Carbonated drink, FD: Functional drink.

All values are mean ± SD.

1)Consumed beverages were separately classified as "health beverage" and "sweetened beverage" based on their potential roles in the health and prevention of obesity in children. Health beverage included milk and soybean milk.

2)Sweetened beverage was defined as all beverages consumed except milk and soybean milk.

3)Milk: included any type of cows' milk

4)Juice: 100% fruit juices, fruit-flavored drinks, and drinks that contained fruit juice in part were combined

5)Sports drinks, diet drinks, traditional drinks and other functional drinks were combined

6)Significantly higher than the juice consumption of boys in summer at P < 0.05

7)Significantly higher than the carbonated beverage consumption of boys in summer at P < 0.01

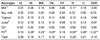

Table 6

HB: Health beverage, SB: Sweetened beverage, CD: Carbonated drink, FD: Functional drink.

All values are mean ± SD.

1)Consumed beverages were separately classified as "health beverage" and "sweetened beverage" based on their potential roles in the health and prevention of obesity in children. Health beverage included milk and soybean milk.

2)Sweetened beverage was defined as all beverages consumed except milk and soybean milk

3)Milk: included any type of cows' milk

4)Juice: 100% fruit juice, fruit-flavored drink, and drink that contained fruit juice in part were combined

5)Sports drink, diet drink, traditional drink and other functional drink were combined

6)Significantly higher than the juice consumption for boys in summer at P < 0.05

7)Significantly higher than the carbonated beverage consumption of boys in summer at P < 0.01

8)Significantly higher than the sweetened beverage consumption of boys in summer at P < 0.05

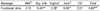

Table 7

*P < 0.05

PHB: Percent energy intake from health beverage to the daily energy intake, PSB: Percent of energy intake from sweetened beverage to the daily energy intake, PAB: Percent energy intake from all beverages to the daily energy intake.

1)All beverages consumed were classified as "health beverage" and "sweetened beverage" based on their potential roles in the health and prevention of obesity of obesity in children. Health beverage included milk and soybean milk.

2)Sweetened beverage was defined as all beverages consumed except milk and soybean milk.

3)Significantly higher than the percentage of boys in summer at P < 0.05

Table 8

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

1)Consumed beverages were separately classified as "health beverage" and "sweetened beverage" based on their potential roles in the health and prevention of obesity in children.

2)Health beverage included milk and soybean milk.

3)Sweetened beverage was defined as all beverages consumed except milk and soybean milk.

Table 9

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Ht: Height, Wt: Weight, BMI: Body Mass Index, FM: Fat Mass, FR: Fat Ratio, W: Waist circumference, H: Hip circumference, WHR: Waist hip girth ratio, CD: Carbonated drink, FD: Functional drink.

1)Milk: milk included any type of cows' milk

2)Juice: Juice included 100% fruit Juice, fruit-flavored drink, and drink that contained fruit juice in part

3)Sports drinks, diet drinks, traditional drinks and other functional drinks were combined.

Table 10

CD: Carbonated drinks, Total: Total amount of all beverages consumed

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

1)Sports drink, diet drink, traditional drink and other functional drink were combined

2)Milk: included any type of cows' milk

3)Juice: 100% fruit Juice, fruit-flavored drink, and drink that contained fruit juice in part were combined

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download