Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

The concept of "food deserts" has been widely used in Western countries as a framework to identify areas with constrained access to fresh and nutritious foods, providing guidelines for targeted nutrition and public health programs. Unlike the vast amount of literature on food deserts in a Western context, only a few studies have addressed the concept in an East Asian context, and none of them have investigated spatial patterns of unhealthy food consumption from a South Korean perspective.

SUBJECTS/METHODS

We first evaluated the applicability of food deserts in a Korean setting and identified four Korean-specific unhealthy food consumption indicators, including insufficient food consumption due to financial difficulty, limited consumption of fruits and vegetables, excessive consumption of junk food, and excessive consumption of instant noodles. The KNHANES 2008-2012 data in Seoul were analyzed with stratified sampling weights to understand the trends and basic characteristics of these eating patterns in each category. GIS analyses were then conducted for the data spatially aggregated at the sub-district level in order to create maps identifying areas of concern regarding each of these indicators and their combinations.

RESULTS

Despite significant reduction in the rate of food insufficiency due to financial difficulty, the rates of excessive consumption of unhealthy foods (junk food and instant noodles) as well as limited consumption of fruits and vegetables have increased or remained high. These patterns tend to be found among relatively younger and more educated groups, regardless of income status.

CONCLUSIONS

A GIS-based analysis demonstrated several hotspots as potential "food deserts" tailored to the Korean context based on the observed spatial patterns of undesirable food consumption. These findings could be used as a guide to prioritize areas for targeted intervention programs to facilitate healthy food consumption behaviors and thus improve nutrition and food-related health outcomes.

Ever since the notion of "food deserts" appeared in social science disciplines, numerous studies have been conducted on its existence, multifaceted impact, and policy implications over the last two decades. The concept of food deserts began to emerge in Western societies in the late 1990s [1], but there is an insufficient consensus surrounding the universal definition of food deserts [2]. Food deserts were initially defined as places in which people do not have easy access to healthy and fresh foods, particularly if they are poor and have limited mobility [3]. While some studies viewed food deserts as a part of food security (composed of food availability, food accessibility, and food utilization) representing spatial inaccessibility to healthy foods [4], other studies emphasized inequities in food accessibility by racial, ethnic, and socio-economic factors [567]. Food deserts also include locations where fast food restaurants are overabundant [8], and a positive relationship between child obesity rates and the percentage of food desert residents was reported [9]. Despite a lack of consensus on the definition of food deserts, efforts to identify areas of concerns with respect to limited accessibility to healthy foods are now regarded as critical to a targeted intervention program for promoting healthy food consumption [10].

Until now, there is a lack of literature on the topic of food deserts from a non-Western perspective. A few studies have addressed the concept of food deserts in a Japanese context using Western measures and reported mixed results [1112]. It was also found that socioeconomic characteristics determining the level of social exclusion were closely associated with relative inaccessibility to healthy foods (e.g. elderly, unemployed, or those who have no car) rather than physical distance to grocery stores in Tokyo [13]. Another study focusing on young Japanese women indicated that increased availability of confectioneries and bread stores in neighborhoods was positively associated with intake amounts of confectioneries and bread, respectively, whereas no association between store availability and individual intake was detected for fresh items such as meat, fish, fruit, vegetables, and rice [14]. It is thus suspected that the conventional concept of food deserts cannot be directly applied to the East Asian context since more complex socio-behavioral and cultural characterization of neighborhood contexts needs to be incorporated for determining areas of concern. Moreover, highly dense populations in small-sized clusters of neighborhoods together with extensive public transportation systems in East Asia could function differently from those in Western countries with regards to food deserts or equivalent areas.

Despite the different interpretation and implication of food deserts in an East Asian context, understanding of the spatial patterns of nutritionally disadvantaged communities could shed further light on unfavorable food consumption environments that potentially influence unhealthy eating behaviors or limited accessibility to affordable healthy food sources. Moreover, potential "at-risk" communities could be spatially clustered, and thus identifying such spatial patterns may allow officials to concentrate on high-risk areas for their intervention activities. Regionally-tailored targeted policies, such as enhancing accessibility to healthy food outlets or community health centers offering nutrition education and campaigns, could effectively improve public health outcomes by reducing risk factors and efficiently allocating limited resources. However, no study has examined the spatial distribution of food consumption patterns in Korea, possibly due to data limitations as well as the lack of discussion on Korean-specific unhealthy food consumption indicators. Thus, we aimed to determine unhealthy food consumption indicators based on the Korean literature and available data for the purpose of detecting food deserts in the Korean context. The GIS (Geographic Information Systems) analyses, along with some statistical tests, were performed with representative population-based data in Seoul to identify areas of concern for unhealthy food intake as well as how they differ in terms of sociodemographic characteristics from the rest of the city.

For the last couple of decades, large grocery stores (megastores, larger than 3,300 m2) have dominated the Korean grocery market. Due to market saturation, megastores created Super Supermarkets (SSM), which are corporate supermarkets that are smaller than megastores (330 m2-3,300 m2). Unlike typical food desert areas in a Western setting where public transportation is not readily available and those without a car may experience limited consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables due to long distances [15], the public transportation system covers most areas in Korea and makes shopping for groceries less dependent on car ownership. Besides, most customers of SSM or traditional markets arrive by walking [16]. As most grocery retailers are located relatively close to one another due to high population density, more food choices are available in Korea.

Even with an abundant number of food and grocery sources, however, insufficient accessibility to affordable healthy foods in Korea has been continuously reported, especially significant nutrition imbalance and food insecurity among low-income populations especially children [171819202122]. Children from low-income neighborhoods tend to show insufficient intake of protein, vegetables, and fresh fruits mainly due to lack of nutritious meal preparation at home as well as proper parental guidance for healthy eating behaviors [17]. In particular, Korean society has experienced "bipolarization of food expenditure", meaning that increased awareness of food safety causes dramatically high demand for fresh and high quality foods (e.g. organic and natural foods) among high-income populations despite price premiums, whereas low-income populations are incentivized to consume inexpensive low quality foods (e.g. processed and junk foods) [2324]. It was reported that people in the top income quartile consume low energy but nutritious foods such as fresh fruits and dairy products while those in the lowest income quartile eat more high energy but less nutritious foods, spending 20% less on groceries than the richest quartile [23]. Whereas fast food is a major source of high energy but low-quality foods in food desert areas in the Western context, people in Korea are highly exposed to diverse kinds of energy-dense foods containing little nutrients (e.g. street food, snack bars, or instant noodles) [25].

Aside from financial affordability, the literature also highlights the impact of unhealthy eating behaviors at the price of convenience or saved time. While consumption frequencies of fruits and vegetables has decreased [26], high energy and low nutrient foods (e.g. instant noodles, fried food, junk food) are more frequently consumed particularly among children, regardless of their income status [272829]. Such diet choices might be influenced by lifestyle or family eating habits [30] or partly due to the food consumption environment around their residence or school where abundant sources of high energy but less nutritious foods are clustered [283132]. Among Korean adults, ramen (i.e. instant noodles) accounts for the biggest portion of intake of high energy and low nutrient foods due to its excessive levels of energy, fat, and sodium, and the Korean population consumes the largest quantity of instant noodles in the world [33]. The popularity of ramen, especially among those who are consistently busy, comes from its convenience and reasonable price.

According to the unique food consumption patterns reported in the Korean literature, financial constraints as well as unhealthy eating behaviors lead to limited accessibility to affordable healthy foods. Considering data availability, we defined four unhealthy food consumption indicators in Korea as a dummy variable (limited vs. not limited or excessive vs. not excessive). The criteria for classification, along with the relevant reference, are summarized in Table 1.

This study used data from the 2008-2012 Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey (KNHANES) collected in Seoul, including 8,616 people who completed both the health examination and dietary survey. The samples were selected by a stratified multi-stage probability sampling design from the total Korean population in order to ensure the generalizability of the findings to the general population in Korea. The data from the nutrition surveys were primarily used, along with data on common characteristics and basic health conditions. Seoul was divided into 424 sub-districts ("dong"), which are sub-municipal level administrative units of the city and are often classified as neighborhoods or sub-neighborhoods [34]. The sub-district information for the residence of every individual included in the sample was acquired and used to spatially aggregate data at the sub-district level for GIS analyses.

Participation in the KNHANES was voluntary and all records were anonymized before analysis. This survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) (IRB: 2008-04EXP-01-C; 2009-01CON-03-2C; 2010-02CON-21-C; 2011-02CON-06-C; 2012-01 EXP-01-2C), and the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas at Dallas determined that this study was exempt from requiring their approval (MR 16-182).

The KNHANES data, when the multi-year data sets are combined for analysis, require a special statistical procedure to handle the stratified and clustered structures of the sample collected by a multi-stage probability sampling design [35]. The combined data from KNHANES 2008 to 2012 were analyzed with pooled sampling weights using the SVY module of Stata, version 14.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA) to accommodate the complex multi-year survey design. To examine differences in the four unhealthy food consumption indicators among different demographic and socioeconomic groups by gender, age, household income, residence type, and education level (only for respondents over 25-years-old), a series of independent sample t-tests and chi-square tests were conducted.

Since the KNHANES data were collected in only 165 subdistricts in Seoul between 2008 and 2012, we employed the areal interpolation technique using ArcGIS, version 10.2 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA), which is a popular geostatistical interpolation method that extends the kriging theory to data aggregated over polygons [36]. A prediction surface was first created from the source polygons and then averaged within the sub-districts with no observed data. Once the GIS maps were created to visualize spatial patterns of unhealthy food consumption indicators, weighted sum overlay analysis was conducted to create a map showing several hotspots with relatively higher joint scores for all unhealthy food consumption indicators used in this study [37]. An equal level of weight was assigned to each of the unhealthy food consumption indicators to construct an additive weighted overlay model (25% for each).

Fig. 1 shows temporal patterns of the four unhealthy food consumption indicators in Seoul, including the rates of food insufficiency due to financial difficulty, limited consumption of fruits and vegetables, excessive consumption of junk food, and excessive consumption of instant noodles. It is evident that the proportion of people consuming insufficient amounts of food due to household financial hardship remarkably decreased over time (from 10% to 2.5%), whereas a growing percentage of people in Seoul consumed limited amounts of fruits and vegetables less than once per day (from 7% to 13%). Rates of excessive consumption (at least twice per week) of junk food (including hamburgers, pizza, and soda) and instant noodles remained at a high level between 13% and 19%. This trend may indicate that socio-behavioral factors, possibly influenced by neighborhood food environments, play a more critical role than financial barriers in determining unhealthy food consumption patterns in Seoul.

The demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the study subjects, grouped by each unhealthy food consumption indicator, are summarized in Table 2. Although no significant difference in gender composition was detected between the groups according to the first two indicators (food insufficiency due to financial difficulty and limited consumption of fruits and vegetables), relatively more male subjects showed excessive consumption of junk food or instant noodles (P < 0.0001). Although the group who suffered food insufficiency due to financial difficulty was relatively older, the younger group appeared to be more vulnerable to limited consumption of fruits and vegetables or excessive consumption of junk food or instant noodles (P < 0.0001). Residents living in a single house were more likely to experience financial difficulty related to food consumption (P < 0.0001) or depend more on consumption of junk food (P = 0.01) or instant noodles (P < 0.0001) compared to those living in apartments. Interestingly, more highly educated people (college or higher) belonged to the group showing excessive consumption of junk food (P < 0.0001) and instant noodles (P = 0.003), implying that those with higher education levels were more likely to prefer convenient sources of energy and nutrition possibly due to their time-constrained lifestyles. However, household income status was significantly associated with only the financially-related food insufficiency indicator (P < 0.0001) and not the others. In summary, more attention regarding unhealthy eating should be given to younger male subjects with a college or higher education, regardless of income status.

Fig. 2(a)-2(d) shows a series of maps of Seoul for sub-district level percentages of people showing (a) insufficient food consumption due to financial difficulty, (b) limited consumption of fruits and vegetables, (c) excessive consumption of junk food, and (d) excessive consumption of instant noodle. The same legend was used for direct comparison across maps, demonstrating a larger area of concern regarding excessive consumption of junk food or instant noodles (Fig. 2(c) and 2(d)) compared to the two other indicators (Fig. 2(a) and 2(b)). Although some areas belong to the highest categories (above 20%) for all four indicators (i.e. northeast region), each map shows a unique pattern of hotspots, some of which are clustered. These maps highlight the neighborhoods where a relatively larger proportion of people presented unhealthy eating patterns, which may exhibit a spatial aspect of social and environmental factors provoking undesirable food consumption patterns in Seoul.

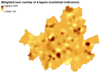

Fig. 3 shows a weighted sum overlay map of about five clusters of hotspots associated with a relatively higher weighted score, integrating all maps of unhealthy food consumption indicators with equal weights (Fig. 2(a)-2(d)). Most hotspots are located in the western and eastern regions of Seoul, which could be viewed as potential "food deserts" tailored to the Korean context. Priority could be given to these areas (i.e. Korean version of "food deserts") in allocating resources for targeted food and nutrition programs, which facilitate healthy food consumption behaviors and provide various sources of healthy and affordable food to the community.

This study is the first to evaluate the applicability of the "food deserts" concept in the Korean context and suggest an alternative approach to identify areas of concern regarding unhealthy food consumption patterns based on findings from the Korean literature. This study defined four Korean-specific unhealthy food consumption indicators, such as insufficient food consumption due to financial difficulty, limited consumption of fruits and vegetables, excessive consumption of junk food, and excessive consumption of instant noodles. While there has been a substantial decline in the rate of food sufficiency due to financial difficulty, all other unhealthy eating patterns have either increased or remained high, particularly among younger and more educated groups. These findings suggest that financial deficit or time-constrained lifestyles can lure people into making suboptimal food choices, which may explain disparities in healthy food intake patterns in the midst of overflowing food sources in highly dense urban regions in Korea. It was also found that social acceptance of undesirable but convenient food products in Korea could lead even high income and highly educated consumers to justify or tolerate unhealthy food consumption. Such efforts to define Korean-specific risk factors may serve as a stepping stone to future nutrition research and practices tailored to the Korean setting.

Unlike Western settings where a geographic barrier is a major concern defining food deserts with limited accessibility to affordable healthy groceries, financial and socio-behavioral barriers appear to be more critical in the Korean context. However, examination of spatial patterns of nutritionally disadvantaged areas would be still valuable in the Korean context since it could assist with further investigation of any undesirable neighborhood environments, which possibly promote unhealthy eating behaviors or elevate exposure to unhealthy food sources [3839]. Considering that communities at risk of unhealthy food intake could be spatially clustered [40], this study used a GIS mapping approach to visualize the spatial aspects of unhealthy food consumption indicators provided by the KNHANES 2008-2012 data available at the sub-district level in Seoul, which has previously not been conducted due to data unavailability [41]. Sub-district level maps of Korea-specific unhealthy food consumption indicators provided in this study highlight communities in Seoul that may exhibit undesirable neighborhood environments resulting in suboptimal food consumption behaviors. The weighted sum overlay map, demonstrating several potential "food deserts" tailored to the Korean context, could be used for targeted intervention to facilitate healthy and informed food choices and improve nutrition and public health outcomes. Overall, this study could offer insights to policy-makers on how to adequately address food insecurity issues and reduce disparities in access to healthy foods in Seoul.

There have been attempts to construct other food metaphors as a way to replace "food deserts", such as "food oceans" representing copious amounts of cheap processed foods around neighborhoods [8] and "food swamps" highlighting overconsumption of extensive amounts of energy-dense foods [42]. Considering more complex aspects of food desert equivalent areas observed in this study, it may be that "food jungles" could represent Korean-specific food consumption environments. According to the GIS analysis in this study, unhealthy food consumption patterns were found to be widespread despite the abundance of various food sources throughout Seoul. Due to limited disposable income combined with cultural emphasis of convenience and time, some could justify or ignore the adverse consequences of their unhealthy food choices, particularly those who are surrounded by undesirable neighborhood environments promoting unhealthy eating behaviors. Children and teenagers become at risk due to restricted consumption of healthy and nutritious foods and excessive consumption of low quality foods when these unhealthy eating habits of adults are passed down. The metaphor of "food jungles" could portray 'law of the jungle'-like environments where an economically and socially disadvantaged population must make smart choices to survive despite being compelled to consume less healthy products among overflowing alternative food choices.

There are several limitations worth mentioning in this study. First, only four indicators were used to characterize unhealthy food consumption patterns in Korea due to limited data availability. A number of contributing factors, including financial, cultural, environmental, and socio-behavioral elements, could better explain a growing trend of unhealthy food consumption in Seoul. Further elucidation of additional indicators within a more comprehensive research framework is required in subsequent studies. Second, although we argued that undesirable neighborhood environments could promote unhealthy eating behaviors or elevate exposure to unhealthy food sources, we could not verify a possible association between neighborhood environments and cultural and behavioral factors embedded in the indicators used in this study. Thus, the spatial approach proposed in this study could be used as a guide to prioritize areas for targeted intervention programs in order to facilitate healthy eating behaviors or provide more healthy food options. Third, although this study is the first attempt to conduct GIS analysis using the KNHANES data aggregated at sub-district level, data covered only 165 out of 424 sub-districts. Areal interpolation technique was used to fill in missing data only for visualization purposes in this study, but the addition of more KNHANES data collected from other sub-districts in subsequent years could help produce more adequate and comprehensive maps. Finally, this study may lack external validity even within Korea since food consumption patterns could vary by urbanity and other socio-demographic structures in different regions of the country. Further extension of this study to other cities in Korea and other countries in East Asia would enhance understanding of the complex structure of food choices and consumption patterns and provide a broader picture of Korean-specific or Asian-specific factors shaping food desert environments beyond its traditional application in Western settings.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Maps of sub-distract level percentages of people showing (a) insufficient food consumption due to financial difficulty, (b) limited consumption of fruits and vegetables, (c) excessive consumption of junk food, and (d) excessive consumption of instant noodles |

References

1. Cummins S, Macintyre S. The location of food stores in urban areas: a case study in Glasgow. Br Food J. 1999; 101:545–553.

2. Walker RE, Keane CR, Burke JG. Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: a review of food deserts literature. Health Place. 2010; 16:876–884.

3. Furey S, Strugnell C, McIlveen MH. An investigation of the potential existence of "food deserts" in rural and urban areas of Northern Ireland. Agric Human Values. 2001; 18:447–457.

4. Kim K, Kim MK, Shin YJ. The concept and measurement of food security. J Prev Med Public Health. 2008; 41:387–396.

5. Moore LV, Diez Roux AV. Associations of neighborhood characteristics with the location and type of food stores. Am J Public Health. 2006; 96:325–331.

6. Galvez MP, Morland K, Raines C, Kobil J, Siskind J, Godbold J, Brenner B. Race and food store availability in an inner-city neighbourhood. Public Health Nutr. 2008; 11:624–631.

7. Gordon C, Purciel-Hill M, Ghai NR, Kaufman L, Graham R, Van Wye G. Measuring food deserts in New York City's low-income neighborhoods. Health Place. 2011; 17:696–700.

8. Carolan MS. Reclaiming Food Security. Abingdon: Routledge;2013.

9. Schafft KA, Jensen EB, Hinrichs CC. Food deserts and overweight schoolchildren: evidence from Pennsylvania. Rural Sociol. 2009; 74:153–177.

10. Jennings A, Cassidy A, Winters T, Barnes S, Lipp A, Holland R, Welch A. Positive effect of a targeted intervention to improve access and availability of fruit and vegetables in an area of deprivation. Health Place. 2012; 18:1074–1078.

11. Hanibuchi T, Kondo K, Nakaya T, Nakade M, Ojima T, Hirai H, Kawachi I. Neighborhood food environment and body mass index among Japanese older adults: results from the Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES). Int J Health Geogr. 2011; 10:43.

12. Iwama N, Tanaka K, Sasaki M, Komaki N, Saito Y. The dietary life of the elderly in local cities and food desert issues: a case study of Mito city, Ibaraki prefecture. Jpn J Hum Geogr. 2009; 61:139–156.

13. Choi Y, Suzuki T. Food deserts, activity patterns, & social exclusion: the case of Tokyo, Japan. Appl Geogr. 2013; 43:87–98.

14. Murakami K, Sasaki S, Takahashi Y, Uenishi K. Japan Dietetic Students' Study for Nutrition and Biomarkers Group. Neighborhood food store availability in relation to food intake in young Japanese women. Nutrition. 2009; 25:640–646.

15. Pearson T, Russell J, Campbell MJ, Barker ME. Do 'food deserts' influence fruit and vegetable consumption?--A cross-sectional study. Appetite. 2005; 45:195–197.

16. Moon S. A study on determining the extent of damage and decreasing rate of supermarket sales by new SSM store. In : The 2010 Fall Conference of KREAA; Seoul: Korea Real Estate Analysts Association;2010. p. 355–375.

17. Park EY, Han SN, Kim HK. Assessment of meal quality and dietary behaviors of children in low-income families by diet records and interviews. Korean J Food Nutr. 2011; 24:145–152.

18. Hwang JY, Ru SY, Ryu HK, Park HJ, Kim WY. Socioeconomic factors relating to obesity and inadequate nutrient intake in women in low income families residing in Seoul. Korean J Nutr. 2009; 42:171–182.

19. Nam KH, Kim YM, Lee GE, Lee YN, Joung H. Physical development and dietary behaviors of children in low-income families of Seoul area. Korean J Community Nutr. 2006; 11:172–179.

20. Jang HB, Park JY, Lee HJ, Kang JH, Park KH, Song J. Association between parental socioeconomic level, overweight, and eating habits with diet quality in Korean sixth grade school children. Korean J Nutr. 2011; 44:416–427.

21. Chun IA, Ryu SY, Park J, Ro HK, Han MA. Associations between food insecurity and healthy behaviors among Korean adults. Nutr Res Pract. 2015; 9:425–432.

22. Kim HJ, Oh K. Household food insecurity and dietary intake in Korea: results from the 2012 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2015; 18:3317–3325.

23. Kim HJ, Lee HJ. Food security in Korea and its policy agendas. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2012; 32:468–499.

24. Kim S, Moon S, Popkin BM. The nutrition transition in South Korea. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000; 71:44–53.

25. Kwon YS, Ju SY. Trends in nutrient intakes and consumption while eating-out among Korean adults based on Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1998-2012) data. Nutr Res Pract. 2014; 8:670–678.

26. Kim Y, Kwon YS, Park YH, Choe JS, Lee JY. Analysis of consumption frequencies of vegetables and fruits in Korean adolescents based on Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey (2006, 2011). Nutr Res Pract. 2015; 9:411–419.

27. Heo GJ, Nam SY, Lee SK, Chung SJ, Yoon JH. The relationship between high energy/low nutrient food consumption and obesity among Korean children and adolescents. Korean J Community Nutr. 2012; 17:226–242.

28. Park S, Choi BY, Wang Y, Colantuoni E, Gittelsohn J. School and neighborhood nutrition environment and their association with students' nutrition behaviors and weight status in Seoul, South Korea. J Adolesc Health. 2013; 53:655–662.e12.

29. Shin HJ, Cho E, Lee HJ, Fung TT, Rimm E, Rosner B, Manson JE, Wheelan K, Hu FB. Instant noodle intake and dietary patterns are associated with distinct cardiometabolic risk factors in Korea. J Nutr. 2014; 144:1247–1255.

30. Lee SY, Ha SA, Seo JS, Sohn CM, Park HR, Kim KW. Eating habits and eating behaviors by family dinner frequency in the lower-grade elementary school students. Nutr Res Pract. 2014; 8:679–687.

31. Seo HS, Lee SK, Nam S. Factors influencing fast food consumption behaviors of middle-school students in Seoul: an application of theory of planned behaviors. Nutr Res Pract. 2011; 5:169–178.

32. Lee JS, Kim J. Vegetable intake in Korea: data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1998, 2001 and 2005. Br J Nutr. 2010; 103:1499–1506.

33. Park J, Lee JS, Jang YA, Chung HR, Kim J. A comparison of food and nutrient intake between instant noodle consumers and non-instant noodle consumers in Korean adults. Nutr Res Pract. 2011; 5:443–449.

34. Seo S, Kim D, Min S, Paul C, Yoo Y, Choung JT. GIS-based association between PM10 and allergic diseases in Seoul: implications for health and environmental policy. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016; 8:32–40.

35. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, Chun C, Khang YH, Oh K. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43:69–77.

36. Goodchild MF, Anselin L, Deichmann U. A framework for the areal interpolation of socioeconomic data. Environ Plan A. 1993; 25:383–397.

37. Carver SJ. Integrating multi-criteria evaluation with geographical information systems. Int J Geogr Inf Syst. 1991; 5:321–339.

38. Lytle LA. Measuring the food environment: state of the science. Am J Prev Med. 2009; 36:S134–S144.

39. Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008; 29:253–272.

40. Austin SB, Melly SJ, Sanchez BN, Patel A, Buka S, Gortmaker SL. Clustering of fast-food restaurants around schools: a novel application of spatial statistics to the study of food environments. Am J Public Health. 2005; 95:1575–1581.

41. Yeom HA, Jung D, Choi M. Adherence to physical activity among older adults using a geographical information system: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examinations Survey IV. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2011; 5:118–127.

42. Rose D, Bodor JN, Swalm CM, Rice JC, Farley TA, Hutchinson PL. Deserts in New Orleans? Illustrations of Urban Food Access and Implications for Policy. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan National Poverty Center/USDA Economic Research Service Research;2009.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download