1. Korea immigraion service, ministry of justice. Korea immigration service statistics 2013. KEWAD;2014.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Vaccine Control. Measles, strengthening of measures to prevent transmission and spread in schools. Measles: 2014. May. 27. press release.

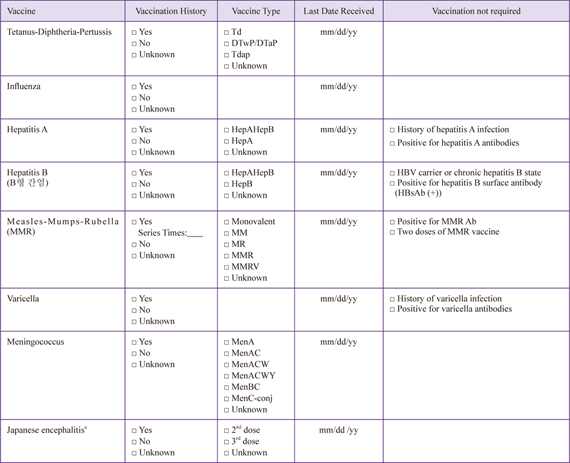

4. Korean Society of Infectious Diseases. Adult vaccination. 2nd ed. Seoul: Koonja Publishing;2012.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women--Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013; 62:131–135.

7. Kwon HJ, Yum SK, Choi UY, Lee SY, Kim JH, Kang JH. Infant pertussis and household transmission in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2012; 27:154–151.

8. Kim IS, Seo YB, Hong KW, Noh JY, Choi WS, Song JY, Cho GJ, Oh MJ, Kim HJ, Hong SC, Sohn JW, Kim WJ, Cheong HJ. Perceptions of Tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccination among Korean women of childbearing age. Infect Chemother. 2013; 45:217–224.

10. Choi WS, Choi JH, Kwon KT, Seo K, Kim MA, Lee SO, Hong YJ, Lee JS, Song JY, Bang JH, Choi HJ, Choi YH, Lee DG, Cheong HJ. Committee of Adult Immunization. Korean Society of Infectious Diseases. Revised adult immunization guideline recommended by the korean society of infectious diseases, 2014. Infect Chemother. 2015; 47:68–79.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Infectious Diseases Web-Statistics System. Accessed 3 November 2014. Accessed at

http://stat.cdc.go.kr.

13. Jacobsen KH. The global prevalence of hepatitis A virus infection and susceptibility: systematic review. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO;2009.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Elimination of measles--South Korea, 2001-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007; 56:304–307.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Progress toward measles elimination--Western Pacific Region, 2009-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 201; 62:443–447.

17. Martin R, Wassilak S, Emiroglu N, Uzicanin A, Deshesvoi S, Jankovic D, Goel A, Khetsuriani N. What will it take to achieve measles elimination in the World Health Organization European Region: progress from 2003-2009 and essential accelerated actions. J Infect Dis. 2011; 204:Suppl 1. S325–S334.

18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Progress toward measles control - African region, 2001-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009; 58:1036–1041.

19. Sadzot-Delvaux C, Rentier B, Wutzler P, Asano Y, Suga S, Yoshikawa T, Plotkin SA. Varicella vaccination in Japan, South Korea, and Europe. J Infect Dis. 2008; 197:Suppl 2. S185–S190.

20. Ozaki T. Varicella vaccination in Japan: necessity of implementing a routine vaccination program. J Infect Chemother. 2013; 19:188–195.

21. Fischer M, Lindsey N, Staples JE, Hills S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Japanese encephalitis vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59(RR-1):1–27.

22. Erlanger TE, Weiss S, Keiser J, Utzinger J, Wiedenmayer K. Past, present, and future of Japanese encephalitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009; 15:1–7.

23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2012 Annual Report on Infectious Disease Monitoring. Accessed 28 June 2013. Available at:

http://www.cdc.go.kr.

25. Erra EO, Hervius Askling H, Rombo L, Riutta J, Vene S, Yoksan S, Lindquist L, Pakkanen SH, Huhtamo E, Vapalahti O, Kantele A. A single dose of Vero cell-derived Japanese encephalitis (JE) vaccine (Ixiaro) effectively boosts immunity in travelers primed with mouse brain-derived JE vaccines. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 55:825–834.

26. Leder K, Tong S, Weld L, Kain KC, Wilder-Smith A, von Sonnenburg F, Black J, Brown GV, Torresi J. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Illness in travelers visiting friends and relatives: a review of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1185–1193.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download