Abstract

Air embolism is a rare complication of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Patent foramen ovale, which is necessary in fetal circulation, is a potential route for emboli arising from the venous system to enter the systemic arterial circulation, resulting in paradoxical air embolism syndrome. A case of paradoxical air embolism during percutaneous nephrolithotomy is presented. To our knowledge, this is the first report of paradoxical air embolism associated with patent foramen ovale during percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

Air embolism during percutaneous nephrolithotomy is rare. However, air pyelogram poses the potential risk of air embolism. Patent foramen ovale, which is necessary in fetal circulation, is a potential route for emboli arising from the venous system to enter the systemic arterial circulation, resulting in paradoxical air embolism syndrome. We report a case of paradoxical air embolism as a complication of percutaneous approach for treatment of calyceal diverticular stone.

A 37-yr-old man in good health was referred to us for right calyceal diverticulum with milk of calcium. Percutaneous approach was planned for treatment of calyceal diverticulum. After induction of general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the lithotomy position. A 6-Fr ureteral catheter with ureteropelvic junction occlusion balloon was passed through the right ureter, and the patient was then turned to prone position. After confirming the position of the ureteral catheter under fluoroscopy, the pyelogram was performed by injecting contrast and a small volume of air into the right pelvocalyceal system to locate the diverticulum (Fig. 1). Direct puncture of the calyceal diverticulum was attempted several times without success. The total volume of air used during the procedure was about 25 mL. The patient remained cardiovascularly stable throughout the procedure. Anesthesia and recovery were uneventful.

Six hours after the surgical procedure, the patient complained of weakness of his right leg. Eight hours after this episode, he had sudden tonic seizure and became unconscious; he was transferred to the intensive care unit and treated, accordingly. The patient underwent magnetic resonance imaging of the brain including diffusion-weighted imaging, which was negative. Twenty-four hours after the procedure, he recovered fully without any neurological deficit and regained consciousness.

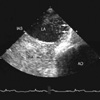

Neurologic evaluation showed that cryptogenic arterial air embolism was the mostly likely cause of the seizure. Cardiac workup with transthoracic echocardiogram failed to reveal a cardiac source of emboli. However, transesophageal echocardiography with provocation testing showed air bubbles in the left atrium revealing that the patient had right-to-left shunt due to patent foramen ovale (Fig. 2). In this case, the clinical features were strongly suggestive of paradoxical air embolism during air pyelogram.

Air embolism, the entry of gas into the vascular structure, is mainly a iatrogenic problem that can result in serious morbidity and even death. Air embolism can involve either the venous or arterial vasculature. Venous embolism occurs when air is introduced to the central venous intravascular space and embolizes to the right heart or pulmonary arterial system. Arterial embolism results from the entry of gas into the left heart chambers, as with paradoxical air embolism across an intracardiac shunt or during cardiac surgery, or directly into the arteries of the systemic circulation such as during decompression barotraumas or penetrating trauma involving an artery (1, 2).

Air embolism is a rare complication of percutaneous nephrolithotomy (3-5). Pyelovenous backflow can cause air embolism. This phenomenon was first described by Lopez, who noted the passage of fluid from the calyces into the renal veins (6). Air embolism as a complication of retrograde pyelography, and air entering the hepatic veins after nephrolithotomy have also been reported (7). The factors that influence morbidity and mortality of air embolism include the volume of air entrained, rate of entrainment, position of patient during the event, and the cardiac status of the patient.

Patent foramen ovale is necessary in fetal circulation to sustain intrauterine life. The closure of the foramen ovale is normally completed by the age of 2 yr. In case of incomplete closure, the foramen ovale is kept sealed by the left atrial to right atrial pressure gradient but may be opened if the right atrial pressure increases and exceeds that of the left atrium (8). A persistent patent foramen ovale is thus a potential route for emboli arising from the venous system to enter the systemic arterial circulation. A patent foramen ovale and paradoxical air embolism syndrome has been increasingly implicated in cryptogenic embolic stroke. The most widely supposed mechanism for a patent foramen ovale related stroke is paradoxical air embolism of venous thrombotic material across the atrial right-to-left shunt (9, 10).

The normal collecting system is known to have a capacity of approximately 5-10 cc. In this case, retrograde injection of 25 mL of air appeared to be the cause of physiologically significant air embolism, most likely via pyelovenous backflow phenomenon. In addition, clinical features of this case strongly suggested paradoxical air embolism associated with patent foramen ovale. A recent study reported that endoscopic operation under carbon dioxide pneumovesicum is effective and safe (11). Although gas embolism is usually air embolism, the medical use of other gases such carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, nitrogen, and helium can also result in embolism. Thus, endoscopic operation using carbon dioxide, which is highly water-soluble and relatively safe, carries potential risk of embolism. To our knowledge, this is the first report of paradoxical air embolism associated with patent foramen ovale during percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

At present, there are no consensual guidelines on the optimal management of patent foramen ovale in patients who have suffered from cryptogenic embolic stroke (12). Urologists who prefer to use air during pecutaneous nephrolithotomy under general anesthesia should be aware of the potential risk of air embolism. Injection of a smaller amount of air for pneumopyelography is strongly advisable, if necessary.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Lee JY, Jo YS, Na SJ, Lee KE, Kim YD. A case of cerebral air embolism after removal of subclavian venous catheter. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2005. 23:712–714.

2. Kwon SC, Kang IG, Kim TW, Kang SC, Won S, Park JK. A case of air embolism during diagnostic hysteroscopy. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 44:1922–1926.

3. Hobin FP. Air embolism complicating percutaneous lithotripsy. J Forensic Sci. 1985. 30:1284–1286.

4. Miller RA, Kellett MJ, Wickham JE. Air embolism, a new complication of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. What are the implications? J Urol (Paris). 1984. 90:337–339.

6. Lopez FA, Dalinka M, Doboy JG. Pyelovenous backflow. Fact, fallacies and significance. Urology. 1973. 2:612–614.

7. Pyron CL, Segal AJ. Air embolism: a potential complication of retrograde pyelography. J Urol. 1983. 130:125–126.

9. Turley AJ, Thambyrajah J, Clarke FL, Stewart MJ. Paradoxical embolism through a patent foramen ovale: an unexpected complication of tracheal extubation. Anaesthesia. 2005. 60:501–504.

10. Droghetti L, Giganti M, Memmo A, Zatelli R. Air embolism: diagnosis with single-photon emission tomography and successful hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Br J Anaesth. 2002. 89:775–778.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download