This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

This study investigated sociodemographic and smoking behavioral factors associated with smoking cessation according to follow-up periods. In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of transdermal nicotine patches, subjects were a total of 118 adult male smokers, who were followed up for 12 months. Univariable logistic regression analysis and stepwise multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the predictors of smoking cessation. The overall self-reported point prevalence rates of abstinence were 20% (24/118) at 12 months follow-up, and there was no significant difference in abstinence rates between placebo and nicotine patch groups. In the univariable logistic regression analysis, predictors of successful smoking cessation were the low consumption of cigarettes per day and the low Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) scores (p<0.05) at 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up. In the stepwise multiple logistic regression analyses, predictors of successful smoking cessation, which were different according to the follow-up periods, were found to be the low consumption of cigarettes per day at the short-term and midterm follow-up (≤6 months), older age, and the low consumption of cigarettes per day at the long-term follow-up (12 months).

Keywords: Smoking Cessation, Demography, Socioeconomic Factors, Randomized Controlled Trials, Follow-up Studies

INTRODUCTION

The predictors of successful smoking cessation have been investigated in many studies (

1-

5). Successful smoking cessation was found to be associated with older age, male gender, a lower consumption of cigarettes per day, owning a home, high social status, and baseline motivation to stop smoking (

6,

7).

Cepeda-Benito et al. reported that nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) was efficacious for women only at short-term (≤3 months) follow-up; however, for men, it was found to be efficacious at all the follow up periods (≤3 months, 6 months, and ≥12 months) (

8). However, to our knowledge, there have been few studies on sociodemographic and smoking behavioral predictors of smoking cessation according to short-term (3 months), midterm (6 months), and long-term (12 months) follow-up periods.

In this randomized clinical trial of transdermal nicotine patches, we examined the sociodemographic and smoking behavioral predictors of smoking cessation according to short-term, midterm, and long-term follow-up periods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which transdermal nicotine patches were used. The study protocol, self-administered questionnaire, and consent form were approved by the institutional review board at the National Cancer Center.

Setting and recruitment

The subjects were all adult male office workers recruited from the company, Kyobo Life insurance Co. We visited the company at baseline and at all the follow-up checkups, owing to the geographical distance between the company and the National Cancer Center. After providing a week's public notice by means of bulletin board announcements at the company and via e-mail, we visited the company, and recruited and enrolled the subjects only for a day on 29 July 2004. All the subjects signed written informed consent form voluntarily.

Sample size estimation

A sample size of 162 was estimated on the basis of the results of a previous study in which the smoking abstinence rates were approximately 40% in the nicotine patch group and 20% in the placebo group, with a power of 80% and an alpha level of 0.05 (

9).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for subjects

To be eligible for this study, subjects had to be between 20 and 55 yr, in good health without any major physical or psychiatric illness, and motivated to quit smoking regardless of their daily cigarette consumption. Subjects were excluded from the study if they 1) had experienced NRT within 6 months before enrollment in the study; 2) were alcohol or narcotic drug abusers; or 3) had allergic skin diseases or heart problems including ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, or any type of arrhythmia or cerebrovascular disease.

Randomization

All the eligible subjects were randomly assigned to receive either nicotine patches or placebo patches according to one of two schedules provided by the computerized randomized plan generator. We stratified the subjects by the severity of nicotine dependence. This was done by generating two randomization schedules: one for the subjects scoring 7 or more on the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) questionnaire; the other, for the subjects scoring below 7 on the questionnaire. A score of 7 or higher was considered to be indicative of high nicotine dependence. This entire random allocation sequence was conducted by a third person and remained unknown until the interventions were blindly assigned to the two groups by the third person.

Treatment period

The total treatment period was 6 weeks. During the first 2 weeks, the subjects in the nicotine patch group wore 30 cm2 transdermal nicotine patches; during the middle 2 weeks, they wore 20 cm2 transdermal nicotine patches; and during the last 2 weeks, they wore 10 cm2 transdermal nicotine patches. The subjects in the placebo patch group wore identical-appearing patches that did not contain nicotine.

Interventions

On the first day of recruitment, all the subjects were given either seven 30 cm2 transdermal nicotine patches with 57 mg of nicotine in each patch, delivering 21 mg/day or seven placebo patches. They were instructed to apply one patch daily and to quit smoking from the very next day after recruitment. The nicotine patch group was given seven additional 30 cm2 nicotine patches on the 1st-week visit day; fourteen 20 cm2 transdermal nicotine patches with 38 mg of nicotine in each patch, delivering 14 mg/day, on the 2nd-week visit day; and fourteen 10 cm2 transdermal nicotine patches with 19 mg of nicotine in each patch, delivering 7 mg/day, on the 4th-week visit day. The placebo patch group was given identical-appearing patches using the same method as that used for the nicotine patch group.

Behavioral counseling and follow-up period

We visited the company at short term (1, 2, 4, and 7 weeks and 3 months); midterm (6 months); and long-term (12 months) periods of follow-up after the start of the study. The subjects were given one-on-one behavioral counseling for about 10 min by three doctors trained in smoking cessation therapy. The subjects who were absent on the appointed counseling day received telephone calls from the doctors, who provided support for smoking cessation and identified whether or not they stopped smoking.

Baseline assessments

At enrollment, the subjects answered a self-administered questionnaire containing questions pertaining to sociodemographic characteristics and smoking behavioral factors, and were also administered the FTND. Sociodemographic characteristics and smoking behavioral predictors included age, smoking initiation age, smoking duration, average daily cigarette consumption, types of tobacco, second-hand smoke, marriage, current diseases, alcohol drinking, exercise, education, monthly income, and previous attempts to quit smoking within the past year. The FTND questionnaire, which consists of 6 questions and was validated in Korea, was used to evaluate the severity of nicotine dependence (score range was from 0 [least dependence] to 10 [highest dependence]). Blood pressure and urine cotinine concentrations were measured at baseline.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the self-reported point prevalence rate of abstinence at 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up. Subjects were considered to be abstinent if at the time of the visit, they reported not having smoked during the previous week. The subjects lost to follow-up, who were both absent at each follow-up and not able to be kept in touch with by telephone, were considered to be smokers. The outcome measure analysis was conducted using the intention-to-treat analysis.

Statistical analysis

Pearson's chi-square test for categorical variables and a two-sample t-test for continuous variables were used to test the baseline differences between the treatment and control groups with regard to the sociodemographic characteristics and smoking behaviors. To study the sociodemographic and smoking behavioral factors and their association with smoking cessation, we first performed univariable logistic regression analyses at the follow-up periods of 3, 6, and 12 months. We then conducted a stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis to determine the predictors of abstinence at the respective follow-up periods. All the statistical tests were two-sided, and p values of 0.05 or less were considered to be statistically significant. Data analyses were performed using SPSS 12.0 K for Windows.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

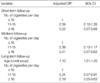

A total of 118 subjects entered the study from July 2004 to August 2005. The baseline characteristics of the study population in the nicotine and placebo patch groups are described in

Table 1. At baseline, there was no significant difference between the nicotine and placebo patch groups with regard to the sociodemographic and lifestyle variables (p>0.05).

Adverse events and dropouts

Adverse events were minimal in both nicotine and placebo patch groups. Some examples of these events were skin reactions at the application site, headaches, insomnia, and dream abnormalities. No serious adverse events were reported in either group. No subject was dropped out; all the subjects who were not present at the time of the scheduled visit were interviewed by telephone.

Univariable logistic regression analysis

Using univariable logistic regression analysis, we identified several sociodemographic and smoking behavioral factors related to the status of abstinence, as a result of the smoking cessation intervention, at different follow-up periods (

Table 2). Throughout all the follow-up periods, the cigarette consumption per day and the FTND scores, which revealed the severity of nicotine dependence, showed a significant difference in the self-reported abstinence rates (

p<0.05).

The overall self-reported point prevalence rates of abstinence were 20.3% (24/118) at 3 months follow-up, 24.6% (29/118) at 6 months follow-up, and 20.3% (24/118) at 12 months follow-up; furthermore, the abstinence rates between the placebo and nicotine patch groups were not significantly different across the follow-up periods. At 12 months follow-up, successful abstinence was significantly associated with increasing age (OR=1.09; 95% CI, 1.01-1.18) and marginally significantly associated with increasing years of smoking cigarettes (OR=1.08; 95% CI, 1.00-1.16).

At 3 months and 12 months follow-up, the baseline urinary cotinine concentration was also inversely associated with the abstinence rate.

However, age at the start of smoking, degree of puff, frequency of attempts to quit smoking in the previous year, marital status, monthly income, education, body mass index (BMI), frequency of alcohol drinking per week, and frequency of exercise per week were not shown to be significantly associated with the smoking abstinence rate.

Stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis

To identify the adjusted predictors of abstinence according to the follow-up periods, we conducted a multiple logistic regression analysis with forward stepwise selection and with an entry criteria of 0.10 and an elimination criteria of 0.10. Age was included in the final model and 'years of smoking cigarettes' was excluded because of its collinearity with age. Moreover, considering the multicollinearity among number of cigarettes per day, FTND score, and baseline urinary cotinine concentration, only the variable of number of cigarettes per day, which showed the strongest association with abstinence rate, was included in the final model.

The final multivariable model showed that only the variable of number of cigarettes per day was the predictor of smoking cessation at short-term and midterm follow-up; however, the variables of age and cigarettes per day were the predictors of smoking cessation at long-term follow-up. The main outcomes of the final model at long-term follow-up were as follows: a higher success rate in the older subjects (adjusted OR=1.10; 95% CI, 1.01-1.20) as well as a lower consumption of cigarettes per day (adjusted OR of 11-15 cigarettes per day compared with ≤10 cigarettes per day=0.24; 95% CI, 0.07-0.91 and for ≥16, adjusted OR=0.19; 95% CI, 0.06-0.63) (

Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Several studies have shown that the main predictors of smoking cessation are age, gender, the daily consumption of tobacco, housing conditions, social status, baseline motivation to stop smoking, and so on (

1,

6,

7).

In the present study, we found that only the number of cigarettes per day was a significant predictor for smoking cessation at short-term (3 months) and midterm (6 months) follow-up; however, at long-term (12 months) follow-up, age and number of cigarettes per day were the predictors of successful smoking cessation.

We do not have a clear answer to why age was found to be a predictor of long-term smoking cessation. However, we can infer that although younger smokers succeeded in quitting smoking at the short-term and midterm follow-up period after the onset of the therapy, compared to older smokers, they were relatively more prone to failing to maintain their smoking cessation; this could be due to less motivation or the thought of other opportunities for smoking cessation in the future. In addition, generally, older subjects tended to maintain smoking cessation better than the younger ones (

2-

4); this is thought to be associated with the fact that older subjects are more likely to be confronted with health deterioration and accompanying medical advice to quit smoking (

1,

2). Among those who did recognize the dangers, there was greater motivation to quit smoking and a greater success rate; for example, among the older subjects, the former smokers believed that smoking definitely increases the chance of developing heart disease to a greater extent than the current smokers (

10,

11).

It has been well known that smokers who smoke few cigarettes per day are more likely to quit and maintain the abstinence than smokers who smoke a large number of cigarettes per day (

6,

7,

12). A high consumption of cigarettes per day is associated with high nicotine dependence and a low smoking cessation rate (

12-

14). In the univariable analysis of our study, the consumption of cigarettes per day, the FTND score, and urinary cotinine concentration were found to be significant predictors of smoking cessation. The correlation coefficients between the consumption of cigarettes per day and the FTND score, between the consumption of cigarettes per day and urinary cotinine concentration, and between the FTND score and urinary cotinine concentration were 0.65, 0.61, and 0.57, respectively, and were all statistically significant. These results were compatible with those of the previous study (

15). In the final model, we included only the consumption of cigarettes per day, which was the strongest contributing factor as a predictor of successful smoking cessation in order to avoid the multicollinearity among the variables.

One interesting finding in the present study was that the point prevalence rate of abstinence was the highest at 6 months follow-up, although generally, the abstinence rate tends to decrease with the passage of time. However, our finding was thought to be associated with the subjects' New Year's resolutions to quit smoking. The 6-month follow-up fell on a day in February 2005, when many smokers in Korea were motivated to try to quit smoking; therefore, the abstinence rate at 6 months follow-up was believed to have increased conversely as compared with the abstinence rate at 3 months follow-up. Contrary to the point prevalence abstinence rates, the continuous abstinence rates decreased linearly as follows: 20.3% at 3 months follow-up, 17.8% at 6 months follow-up, and 15.3% at 12 months follow up (data not shown).

The main limitations of our study were as follows: 1) we could not present the continuous abstinence rate validated with an expired CO concentration or urinary cotinine concentration, owing to the non-compliance of the subjects at the follow-up periods; only 9 among 24 subjects, who reported abstinence at 12 months follow up, took the urinary cotinine examination; 2) the inclusion of only males in a localized workplace reduced the generalizability of these findings; and 3) we could not confirm that the difference between the direct visit counseling and the telephone interview would influence the abstinence rate.

In conclusion, this study was the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of nicotine patch to show that sociodemographic and smoking behavior factors associated with successful smoking cessation were different according to the follow-up periods. The results of this study can aid physicians to clinically help smokers to quit smoking in smoking cessation units. In the future, further studies on larger populations including women will be needed to investigate more predictors for successful smoking cessation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to all residents from the Department of Family Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital for their contributions to this study.

References

1. Grøtvedt L, Stavem K. Association between age, gender and reasons for smoking cessation. Scand J Public Health. 2005. 33:72–76.

2. Gourlay SG, Forbes A, Marriner T, Pethica D, McNeil JJ. Prospective study of factors predicting outcome of transdermal nicotine treatment in smoking cessation. BMJ. 1994. 309:842–846.

3. Levy DT, Romano E, Mumford E. The relationship of smoking cessation to sociodemographic characteristics, smoking intensity, and tobacco control policies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005. 7:387–396.

4. Raherison C, Marjary A, Valpromy B, Prevot S, Fossoux H, Taytard A. Evaluation of smoking cessation success in adults. Respir Med. 2005. 99:1303–1310.

5. Van Der Rijt GA, Westerik H. Social and cognitive factors contributing to the intention to undergo a smoking cessation treatment. Addict Behav. 2004. 29:191–198.

6. Osler M, Prescott E. Psychosocial, behavioural, and health determinants of successful smoking cessation: a longitudinal study of Danish adults. Tob Control. 1998. 7:262–267.

7. Monsó E, Campbell J, Tønnesen P, Gustavsson G, Morera J. Sociodemographic predictors of success in smoking intervention. Tob Control. 2001. 10:165–169.

8. Cepeda-Benito A, Reynoso JT, Erath S. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation: differences between men and women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004. 72:712–722.

9. Fiore MC, Kenford SL, Jorenby DE, Wetter DW, Smith SS, Baker TB. Two studies of the clinical effectiveness of the nicotine patch with different counseling treatments. Chest. 1994. 105:524–533.

10. Connolly MJ. Smoking cessation in old age: closing the stable door. Age Ageing. 2000. 29:193–195.

11. Ruchlin HS. An analysis of smoking patterns among older adults. Med Care. 1999. 37:615–619.

12. Farkas AJ, Pierce JP, Zhu SH, Rosbrook B, Gilpin EA, Berry C, Kaplan RM. Addiction versus stages of change models in predicting smoking cessation. Addiction. 1996. 91:1271–1280.

13. Vink JM, Willemsen G, Beem AL, Boomsma DI. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence in a Dutch sample of daily smokers and ex-smokers. Addict Behav. 2005. 30:575–579.

14. Quist-Paulsen P, Bakke PS, Gallefoss F. Predictors of smoking cessation in patients admitted for acute coronary heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005. 12:472–477.

15. Park SM, Son KY, Lee YJ, Lee HC, Kang JH, Lee YJ, Chang YJ, Yun YH. A preliminary investigation of early smoking initiation and nicotine dependence in Korean adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004. 74:197–203.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download