Abstract

Objectives

Disasters exert substantial effects on the mental health of victims and bereaved populations. Thus, a systematic framework for preparing and providing psychosocial and mental health services is necessary. The current attitudes toward and knowledge of disaster mental health-related factors among the general population provides one component for development of the disaster mental health services framework.

Methods

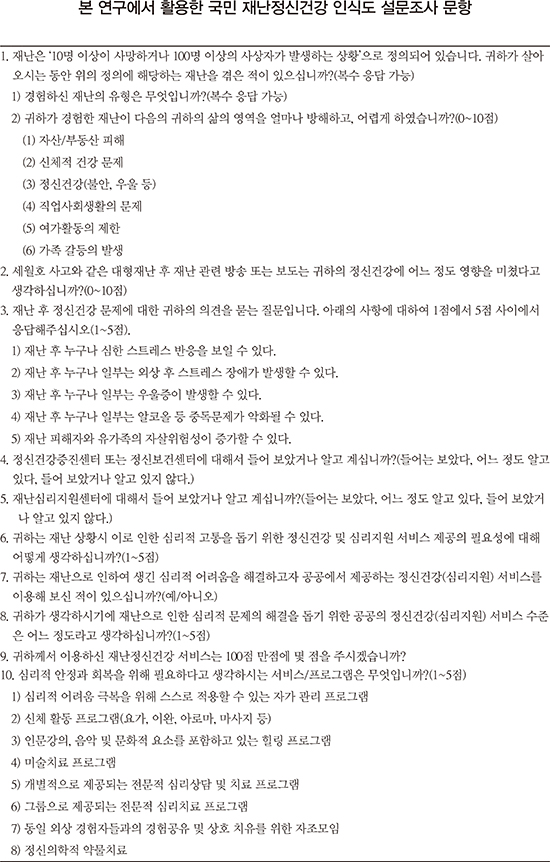

The authors analyzed a web-based survey for disaster mental health-related factors among the general population. Responses for the knowledge and perception for the disaster mental health services were compared between people who experienced and did not experience disaster.

Results

One thousand and three people completed the questionnaire. One hundred and seventy (16.9%) people experienced more than one disaster. People who experienced a disaster were more disturbed by disaster broadcasting or reporting than people who had not. People who experienced a disaster gave disaster mental health services an average score 63.5. People who experienced a disaster perceived group psychotherapy and self-help meetings as less important than those who had not. The recognition of both community mental health center and disaster mental health center was higher in the experienced group than non-experienced.

Conclusion

This study revealed that general satisfaction with the current disaster mental health service is low, particularly among people who have used disaster mental health services. A national mental health system for disaster victims should be established with consideration for efficiency, effectiveness and accessibility.

References

1. Tsutsumi A, Izutsu T, Ito A, Thornicroft G, Patel V, Minas H. Mental health mainstreamed in new UN disaster framework. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015; 2:679–680.

2. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Boden JM, Mulder RT. Impact of a major disaster on the mental health of a well-studied cohort. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014; 71:1025–1031.

3. Yamashita J, Shigemura J. The Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami, and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident: a triple disaster affecting the mental health of the country. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013; 36:351–370.

4. Homma M. Development of the Japanese National Disaster Medical System and Experiences during the Great East Japan Earthquake. Yonago Acta Med. 2015; 58:53–61.

5. Hyogo Institute for Traumatic Stress. Hyogo Institute for Traumatic Stress. 2004. cited 2014 Dec 9. Available from: http://j-hits.org.

6. DMHISS National Information Center of Disaster Mental Health [homepage on the Internet]. Tokyo: DMHISS National Information Center of Disaster Mental Health;cited 2016 May 9. Available from: http://saigai-kokoro.ncnp.go.jp/.

7. Bromet EJ, Hobbs MJ, Clouston SA, Gonzalez A, Kotov R, Luft BJ. DSM-IV post-traumatic stress disorder among World Trade Center responders 11-13 years after the disaster of 11 September 2001 (9/11). Psychol Med. 2016; 46:771–783.

8. Lin S, Lu Y, Justino J, Dong G, Lauper U. What happened to our environment and mental health as a result of hurricane Sandy. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2016; 10:314–319.

9. Department of Health. Planning for the psychosocial and mental health care of people affected by major incidents and disasters: interim national strategic guidance. 2009. cited 2016 May 9. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/

http:/www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_103563.pdf.

10. Daegu City. The Daegu City fire white paper. Daegu: Daegu City;2005.

11. Kim GH, Kwon SJ, Kim SJ. The influence of disaster for psychological health of Taean residents: focusing on the 2- and 8-months after the disaster. Taean: Taean Academic Conference Sourcebook;2009. p. 232–235.

12. Korea Mental Health Foundation Disaster Mental Health Committee. Korean neuropsychiatric association 100 days of records. Seoul: Korea Mental Health Foundation Disaster Mental Health Committee;2014.

13. Perrin MA, DiGrande L, Wheeler K, Thorpe L, Farfel M, Brackbill R. Differences in PTSD prevalence and associated risk factors among World Trade Center disaster rescue and recovery workers. Am J Psychiatry. 2007; 164:1385–1394.

14. Mills MA, Edmondson D, Park CL. Trauma and stress response among Hurricane Katrina evacuees. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97:Suppl 1. S116–S123.

15. Bryant RA. Recovery after the tsunami: timeline for rehabilitation. Clin Psychiatry. 2006; 67:Suppl 2. 50–55.

16. Lee WS, Bae JY. Asymmetric bias of the Ferry Sewol accident news frame - discriminatory aspects and interpretive of media. Korean J Commun Inf. 2015; (71):274–298.

17. Jung SY. Can the disastrous results of media coverage on Sewol Ferry disaster be restored? - a theoretical exploration for paradigm shift of journalism norms. Commun Theor. 2015; 11:56–103.

18. Bang MS. Challenges and lessons of media reports of Sewol Ferry Disaster. Kwanhoon J. 2014; 131:13–26.

19. Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2016 Mental health service guide. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2016.

20. Kim DR, Kim DM. [1-year after Sewol Ferry disaster] People still under

distress. Newsis. 2015. 04. 09.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download