1. Dai X, Gakidou E, Lopez AD. Evolution of the global smoking epidemic over the past half century: strengthening the evidence base for policy action. Tob Control. 2022; 31(2):129–137. PMID:

35241576.

2. World Health Organization. WHO Tobacco Free Initiative. Tobacco: Deadly in Any Form or Disguise. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2006.

3. World Health Organization. WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Use 2000-2025, Fourth Edition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2021.

4. GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020; 396(10258):1223–1249. PMID:

33069327.

5. Zahra A, Cheong HK, Park JH. Burden of disease attributable to smoking in Korea. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2017; 29(1):47–59. PMID:

28198651.

7. Kim Y. Relative-risk of smoking-attributable mortality in Korean adults. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2016; 9(8):134–138.

8. Cho B, Lee HJ, Gong YH, Jo MW. Economic burden of smoking related premature death using willingness to pay on quality-adjusted life years. Public Health Aff. 2017; 1(1):177–191.

9. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Because of Smoking: Domestic Fatalities and the Socio-Economic Costs Attributable to Smoking. Osong, Korea: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency;2022.

10. Park EH, Jung KW, Park NJ, Kang MJ, Yun EH, Kim HJ, et al. Cancer Statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2021. Cancer Res Treat. 2024; 56(2):357–371. PMID:

38487832.

11. Lee EH, Park SK, Ko KP, Cho IS, Chang SH, Shin HR, et al. Cigarette smoking and mortality in the Korean Multi-center Cancer Cohort (KMCC) study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2010; 43(2):151–158. PMID:

20383048.

12. Gunter R, Szeto E, Jeong SH, Suh S, Waters AJ. Cigarette smoking in South Korea: a narrative review. Korean J Fam Med. 2020; 41(1):3–13. PMID:

31189304.

13. Lee S, Kimm H, Yun JE, Jee SH. Public health challenges of electronic cigarettes in South Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2011; 44(6):235–241. PMID:

22143173.

14. Sun T, Anandan A, Lim CC, East K, Xu SS, Quah AC, et al. Global prevalence of heated tobacco product use, 2015-22: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2023; 118(8):1430–1444. PMID:

37005862.

15. Lee Y, Kim K, Kang H, Cho S, Kim S, Kim M, et al. An evidence-based literature review and evaluation of tobacco control policy in Korea: policy implications for young adults. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2020; 40(2):616–650.

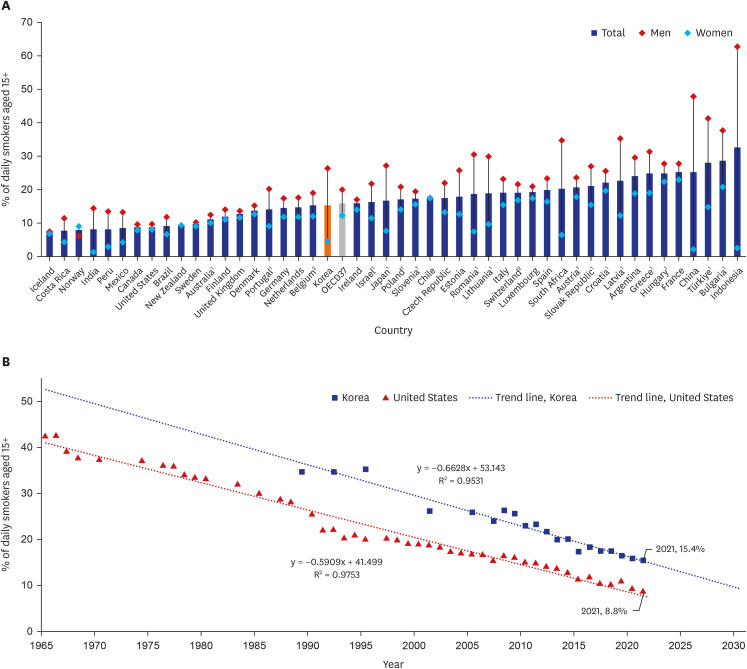

16. OECD. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. Paris, France: OECD Publishing;2023.

17. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43(1):69–77. PMID:

24585853.

18. Kim Y, Choi S, Chun C, Park S, Khang YH, Oh K. Data resource profile: the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBS). Int J Epidemiol. 2016; 45(4):1076–1076e. PMID:

27380796.

19. Collaborators GB. GBD 2019 Tobacco Collaborators. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021; 397(10292):2337–2360. PMID:

34051883.

20. Choi EJ. Tobacco control and prevention of tobacco use in the United States and policy implications. Health Welf Policy Forum. 2012; 4:82–89.

21. Alberg AJ, Shopland DR, Cummings KM. The 2014 Surgeon General’s report: commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the 1964 Report of the Advisory Committee to the US Surgeon General and updating the evidence on the health consequences of cigarette smoking. Am J Epidemiol. 2014; 179(4):403–412. PMID:

24436362.

23. Cho KS. Prevalence of hardcore smoking and its associated factors in Korea. Pogon Sahoe Yongu. 2013; 33(1):603–628.

25. World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. New Delhi, India: World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia;2004.

27. Park JG, Park JW, Seo HG, Lee JS, Kim IS, Kim YI, et al. Tobacco control in the Republic of South Korea, an Asian example. Boyle P, Gray N, Henningfield J, Seffrin J, Zatonski W, editors. Tobacco: Science, Policy and Public Health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press;2010. p. 263–268.

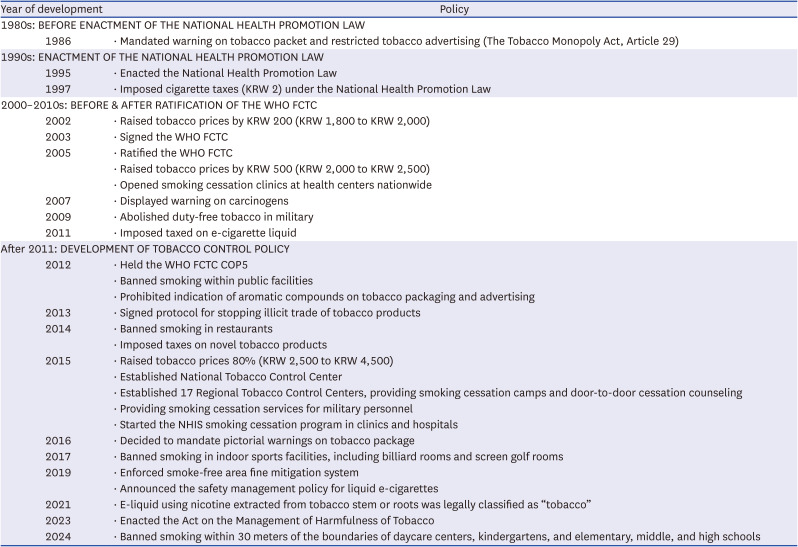

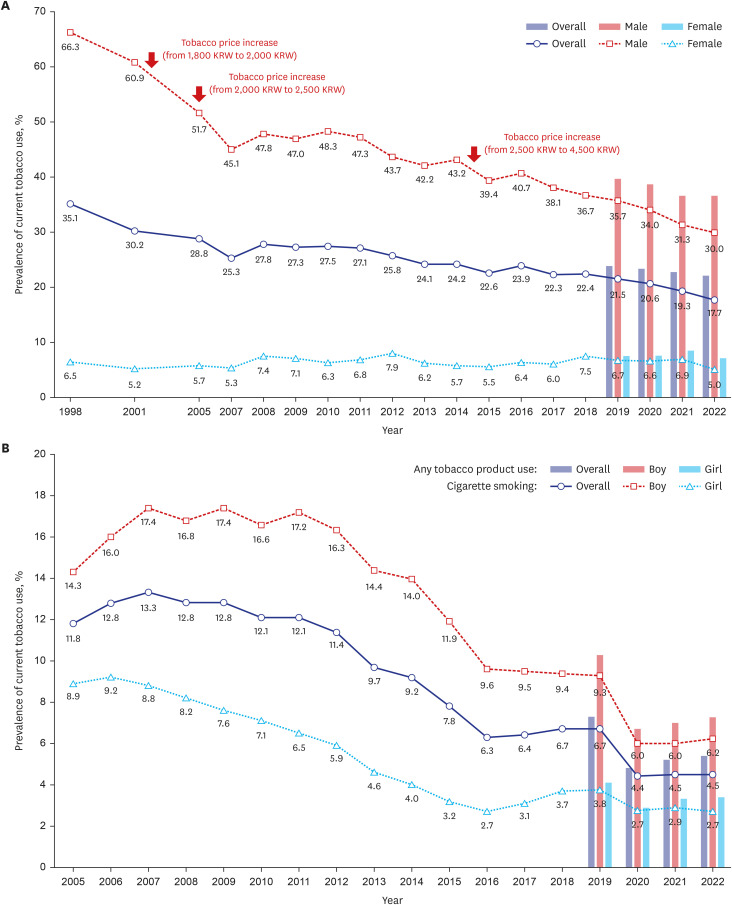

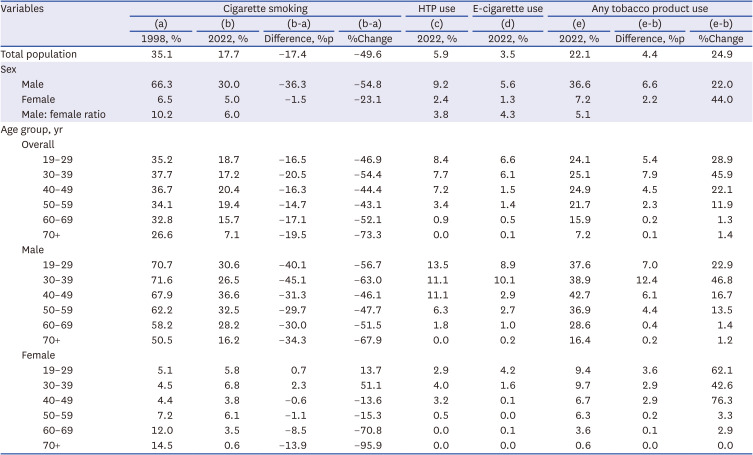

28. Choi S, Kim Y, Oh K. Tobacco control policy and smoking trends in Korea. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2017; 10(21):530–533.

29. Oh JK, Han M, Lim MK. Short-term effects of national smoking cessation service on smoking-related disease prevalence and healthcare costs: experience from the National Health Insurance Service Smoking Cessation Intervention Program in Korea. Tob Induc Dis. 2023; 21:107. PMID:

37637229.

30. Korean Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. Results of the 2023 Out-of-School Youth Survey. Sejong, Korea: Korean Ministry of Gender Equality and Family;2023.

31. Lee S, Kim J. Evolution of tobacco products. J Korean Med Assoc. 2020; 63(2):88–95.

32. Lee S, Kim Y, Kim J, Park S, Cho Si. Changes in the domestic tobacco market and tobacco products, and challenges to prepare strategies for response. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2023; 16(41):1390–1406.

33. Yang Y. Tobacco Control Fact Sheet No. 39. Current Status of Heated Tobacco Products Regulations. Seoul, Korea: National Tobacco Control Center of Republic of Korea;2021.

34. Park MB, Kim CB, Nam EW, Hong KS. Does South Korea have hidden female smokers: discrepancies in smoking rates between self-reports and urinary cotinine level. BMC Womens Health. 2014; 14(1):156. PMID:

25495192.

36. Kim H. Cigarette smoking among people with disabilities: longitudinal analyses. Pogon Sahoe Yongu. 2018; 38(4):341–366.

37. Yeob KE, Kim SY, Kim YY, Park JH. Nationwide prevalence and trends in cigarette smoking among adult men with and without disabilities in South Korea between 2009 and 2017. Public Health. 2023; 222:92–99. PMID:

37536197.

38. Hecht SS, Szabo E. Fifty years of tobacco carcinogenesis research: from mechanisms to early detection and prevention of lung cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2014; 7(1):1–8. PMID:

24403288.

39. Rodgman A, Perfetti TA. The Chemical Components of Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press;2013.

40. Bovet P, Banatvala N, Gedeon J, Peruga A. Tobacco Use: Burden, Epidemiology and Priority Interventions. Noncommunicable Diseases. London, UK: Routledge;2023. p. 134–140.

41. Korea Disease Cont rol and Prevention Agency, Tobacco Control Integrated Knowledge Center. 2022 KDCA Report on Harmful Effects of Tobacco: An Overview of Tobacco Use and its Effects on Health. Osong: Korea Disease Cont rol and Prevention Agency;2022.

42. Park SE, Song HR, Kim CH, Ko SK. Economic burden of smoking in Korea, 2007. Korean J Health Promot. 2008; 8(8):219–227.

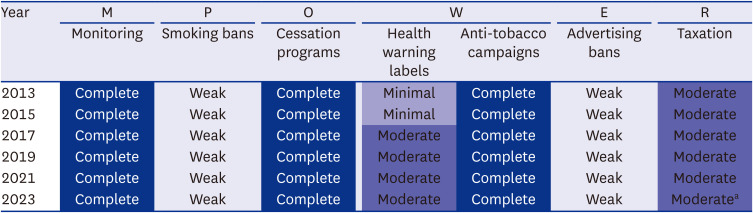

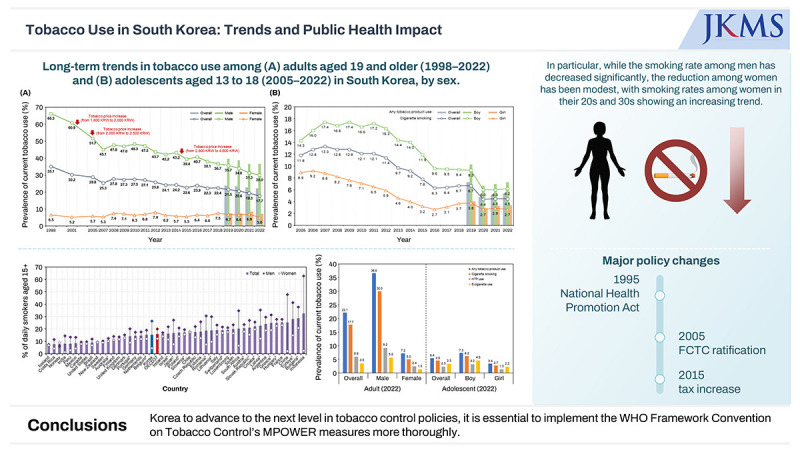

43. Kong J, Lim S, Choi S, Kim G. Status and challenges of implementing tobacco control policies in Korea: focus on WHO MPOWER measures. J Korean Soc Res Nicotine Tob. 2023; 14(2):21–32.

44. Cho H, Oh MY. An investigation of regulations on cigarette advertising, promotion, and sponsorship and promotional guidelines for public policy. Health Welf Policy Forum. 2009; 6:59–71.

45. Park EH. Tobacco Control Fact Sheet No. 48. Tobacco Taxation. Seoul, Korea: National Tobacco Control Center of Republic of Korea;2022.

46. Korea Health Promotion Institution. Tobacco Control Policy Infographic: Comparative Analysis of Cigarette Prices in Korea. Seoul, Korea: Korea Health Promotion Institution;2023.

48. World Health Organization. WHO Technical Manual on Tobacco Tax Policy and Administration. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2021. p. 343.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download