Males constituted 65.2% of the prehypertension cohort (n=60,084). Additionally, women

were found to consume less alcohol (32.0% vs. 80.7% for never drinking) and to

exercise less frequently (46.4% vs. 65.0% for never exercising) compared to men.

Among the men, 44.1% were current smokers (n=25,201), whereas only 1.7% of women

smoked currently (n=577). Similarly, in the prediabetes cohort, men made up 65.4% of

the subjects (n=37,836). The percentage of women who neither exercised (47.2% vs.

67.7%) nor consumed alcohol (29.8% vs. 80.9%) was lower compared to men. In this

cohort, 41.8% of men (n=15,144) were current smokers, while only 2.2% of women

(n=432) were smokers. Furthermore, the prevalence of BMI over 25.0 kg/m

2

was lower in women than in men in both cohorts (32.3% vs. 28.5% in the

prehypertension cohort and 38.1% vs. 36.7% in the prediabetes cohort). The general

characteristics of subjects according to group are summarized in

Table 1.

Table 2 presents the incidence of diseases

during follow-up in subjects with prehypertension and prediabetes, categorized by

gender. In the prehypertension cohort, there were 3,979 MACE cases in men and 2,290

in women. The MACE incidence rates were similar between genders (62.6/10,000 PY for

men vs. 62.1/10,000 PY for women; P=0.724). However, a significant difference was

observed in all-cause mortality rates, with men showing a higher rate than women

(47.1/10,000 PY vs. 24.3/10,000 PY; P<0.001). In the prediabetes cohort,

3,435 MACE cases were recorded in men and 1,904 in women. The incidence rate of MACE

in women was slightly higher than in men, but this difference was not statistically

significant (88.0/10,000 PY for women vs. 92.8/10,000 PY for men; P=0.063). However,

there was a significant difference in all-cause mortality between men and women,

with men experiencing a higher rate (66.7/10,000 PY vs. 41.4/10,000 PY;

P<0.001).

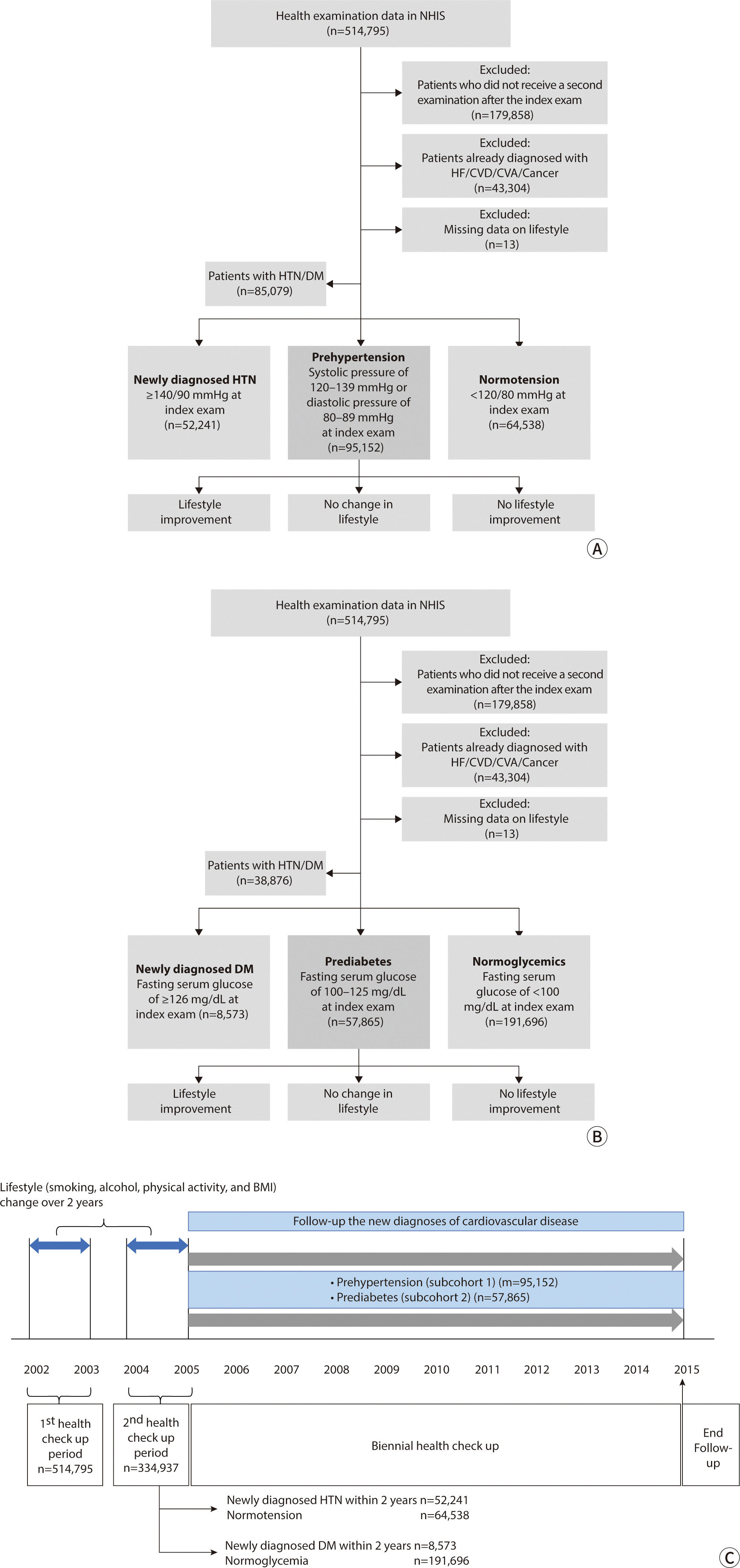

By controlling for lifestyle and clinical factors at the initial health screening, we

evaluated the effects of lifestyle changes on major outcomes using a multivariate

model (

Tables 3,

4). In the prehypertension group, 7,376 patients (7.75%) had

already been diagnosed with T2D, and 2,601 (2.73%) were taking anti-hyperglycemic

medication. Similarly, in the prediabetes group, 11,577 patients (20.01%) had been

diagnosed with HTN, and 8,962 (15.49%) were on antihypertensive medication (

Table 1). To isolate the effects of medication,

the multivariate analysis accounted for the impact of antihypertensive drugs,

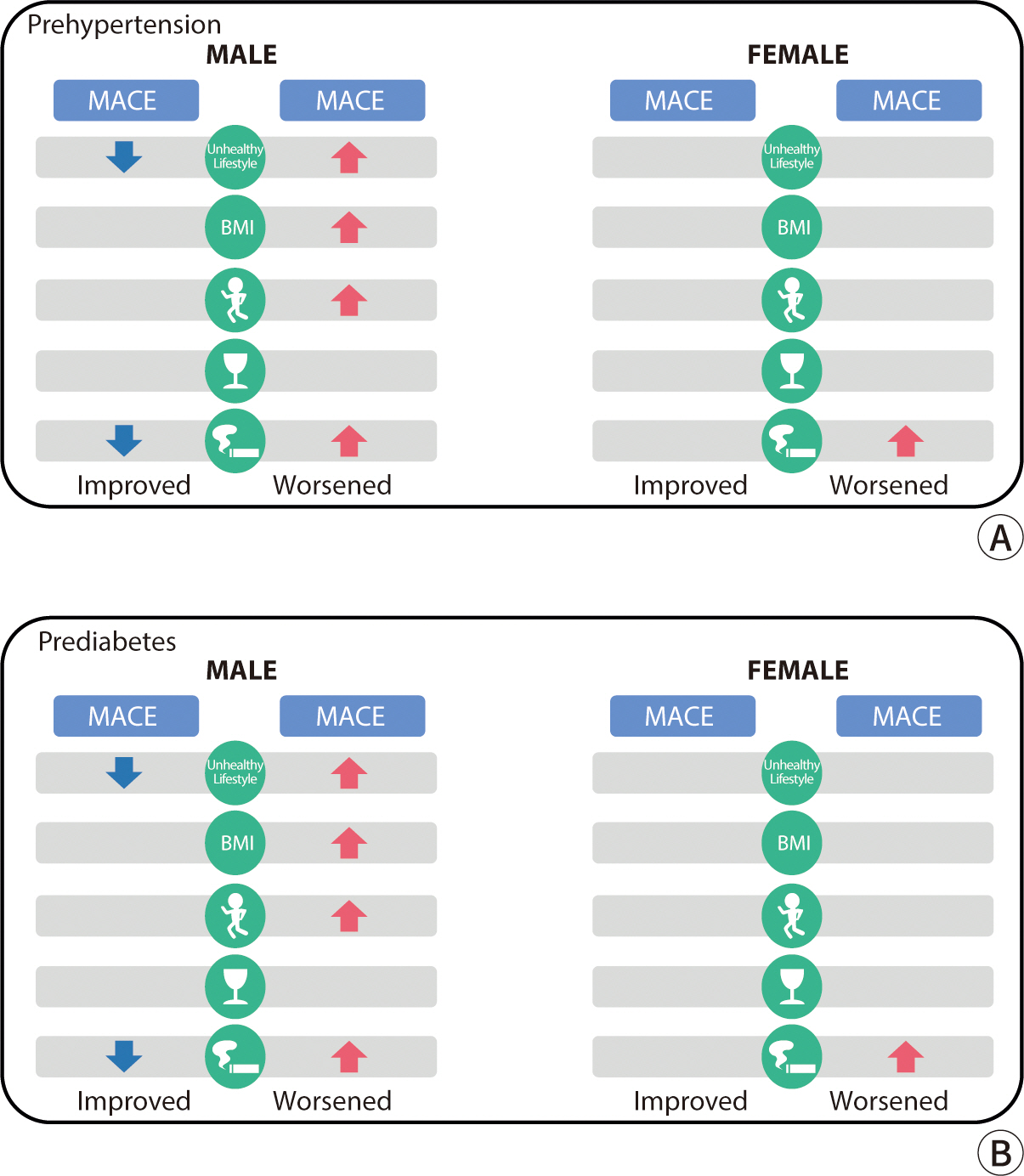

anti-hyperglycemic drugs, and aspirin. In men with prehypertension, the risk of MACE

increased if their lifestyle worsened (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.04–1.23, P=0.004),

particularly if they gained weight (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.03–1.28, P=0.010) or

started smoking (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.17–1.55, P<0.001). For women with

prehypertension, the risk of MACE was higher for those who started smoking (HR,

1.69; 95% CI, 1.15–2.49, P=0.008) or reduced their physical activity (HR,

1.25; 95% CI, 1.06–1.47, P=0.010). Conversely, in men with prehypertension,

improving lifestyle factors reduced the risk of MACE (HR, 0.91; 95% CI,

0.84–0.99, P=0.025), particularly through smoking cessation (HR, 0.79; 95%

CI, 0.70–0.89, P<0.001), drinking less (HR, 1.09; 95% CI,

1.00–1.20, P=0.048), or increasing physical activity (HR, 0.91; 95% CI,

0.84–0.99, P=0.027). In men with prediabetes, those whose lifestyle factors

worsened had a 23% higher risk of MACE compared to those with no lifestyle changes

(HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.12–1.35, P<0.001). An increased risk of MACE was

also observed in those who gained weight (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06–1.33,

P=0.003), started smoking (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.22–1.64, P<0.001), or

decreased their physical activity (HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.09–1.35,

P<0.001). Additionally, in men with prediabetes, a reduction in alcohol

consumption was linked to a higher risk of MACE (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.07–1.29,

P=0.001). In women with prediabetes, the risk of MACE was 1.24 times higher for

those who gained weight compared to those with no change in BMI levels (HR, 1.24;

95% CI, 1.06–1.45, P=0.006). As weight change can be a consequence of

lifestyle changes, the association between unhealthy lifestyles, excluding BMI, and

MACE was evaluated. Among pre-hypertensive men, those whose lifestyles worsened had

a higher risk of MACE (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.02–1.20, P=0.022). Among

pre-hypertensive women, those whose lifestyles improved tended to have a lower MACE

risk, although this association was not statistically significant (HR, 0.91; 95% CI,

0.81–1.01, P=0.072) (

Table 3,

Supplement 3). In the

prediabetes group, men whose lifestyles worsened showed a significantly higher risk

of MACE (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.12–1.35, P<0.001), while there was no

significant difference in MACE risk among comparative female subjects (

Table 4,

Supplement 4).

To mitigate the risk of reverse causality, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by

excluding cardiovascular events that occurred within two years following the

observation of lifestyle changes. In the prehypertension male group, the risk of

MACE increased among subjects who experienced a decline in lifestyle quality, gained

weight, decreased their physical activity frequency, or began smoking between

biennial screenings. Conversely, the risk decreased in those who improved their

lifestyles or quit smoking. In the prehypertension female group, an increase in MACE

risk was observed in subjects who started smoking (

Fig. 2A). In the prediabetes group, the MACE risk escalated in men who

worsened their lifestyle, gained weight, reduced their physical activity frequency,

or started smoking between the biennial screenings. In women, the risk increased

among those who gained weight (

Fig. 2B).

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download