Abstract

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to pose significant public health

challenges in Korea, with syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, Mycoplasma

genitalium, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) being the most

prevalent. This review provides an updated overview of the epidemiology,

diagnosis, and treatment of these significant STIs in Korea, highlighting recent

trends and concerns. Syphilis incidence rates have fluctuated due to changes in

surveillance systems. Starting in 2024, syphilis will be reclassified as a

nationally notifiable infectious disease (category 2). Gonorrhea remains a

concern due to increasing antibiotic resistance, including the emergence of

extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains,

underscoring the need for vigilant antimicrobial stewardship. Chlamydia

continues to be the most commonly reported STI, although its incidence has

declined during the COVID-19 pandemic. M. genitalium has gained

attention as a significant STI with rising antibiotic resistance issues,

necessitating updated treatment guidelines and consideration of resistance

testing. HSV-2 remains a common cause of genital herpes, with steady incidence

rates reported. Updated diagnostic methods, including nucleic acid amplification

tests, and revised treatment guidelines are presented to effectively address

these infections. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on other STIs within Korea

remains unclear, necessitating further research. Changes in treatment

guidelines, such as the recommendation of doxycycline as first-line therapy for

chlamydia, reflect evolving evidence and resistance patterns. The importance of

updated diagnostic tools, including resistance testing for M.

genitalium, is emphasized to improve treatment outcomes. Continued

efforts in education, prevention, and research are essential to manage and

mitigate the impact of STIs on public health in Korea.

Go to :

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are commonly encountered in outpatient

clinics. The major STIs primarily addressed in both domestic and international

treatment guidelines include syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex

virus (HSV) infection [1–4]. Recently, the incidence and significance

of Mycoplasma genitalium have been on the rise [5]. The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly

affected access to healthcare services, thereby altering the epidemiology of

major STIs. It has notably impacted access to HIV services, influencing

transmission rates [6,7]. Additionally, there has been a decline

in the incidence of new HIV cases in Korea after COVID-19 [8]. Some studies suggest that this reflects a genuine

reduction in incidence rates [8]. The

impact on other STIs within the country remains unclear.

This review focuses on syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, M.

genitalium, and HSV. While genital warts or condyloma acuminata are

also prevalent STIs [9], they will be

addressed separately at a later date.

Go to :

As this study is a literature review, it did not require institutional review board

approval or individual consent.

Go to :

Syphilis is a disease that has been known for centuries, with documented cases

appearing in European and various other countries' records from the 11th to

15th centuries [10]. Historical documents

from the Joseon Dynasty in Korea also contain references to syphilis.

In Korea, syphilis is classified under the Infectious Disease Control and Prevention

Act as both a Category 4 communicable disease (Article 2, Item 5) and a STI (Item

10). It is monitored alongside six other STIs—gonorrhea, chlamydia infection,

chancroid, genital herpes, condyloma acuminatum, and human papillomavirus

infection—through designated sentinel surveillance institutions. However,

starting in 2024, it has been reclassified as a nationally notifiable infectious

disease (category 2 communicable disease), and data on its occurrence will be

collected once again [11]. The surveillance

system for syphilis has seen several changes over the years. Initially introduced in

2001, the sentinel surveillance system managed syphilis until 2010. It then

transitioned to full-scale surveillance following a reorganization of the legal

classification system for infectious diseases in 2010, only to revert to sentinel

surveillance in 2020.

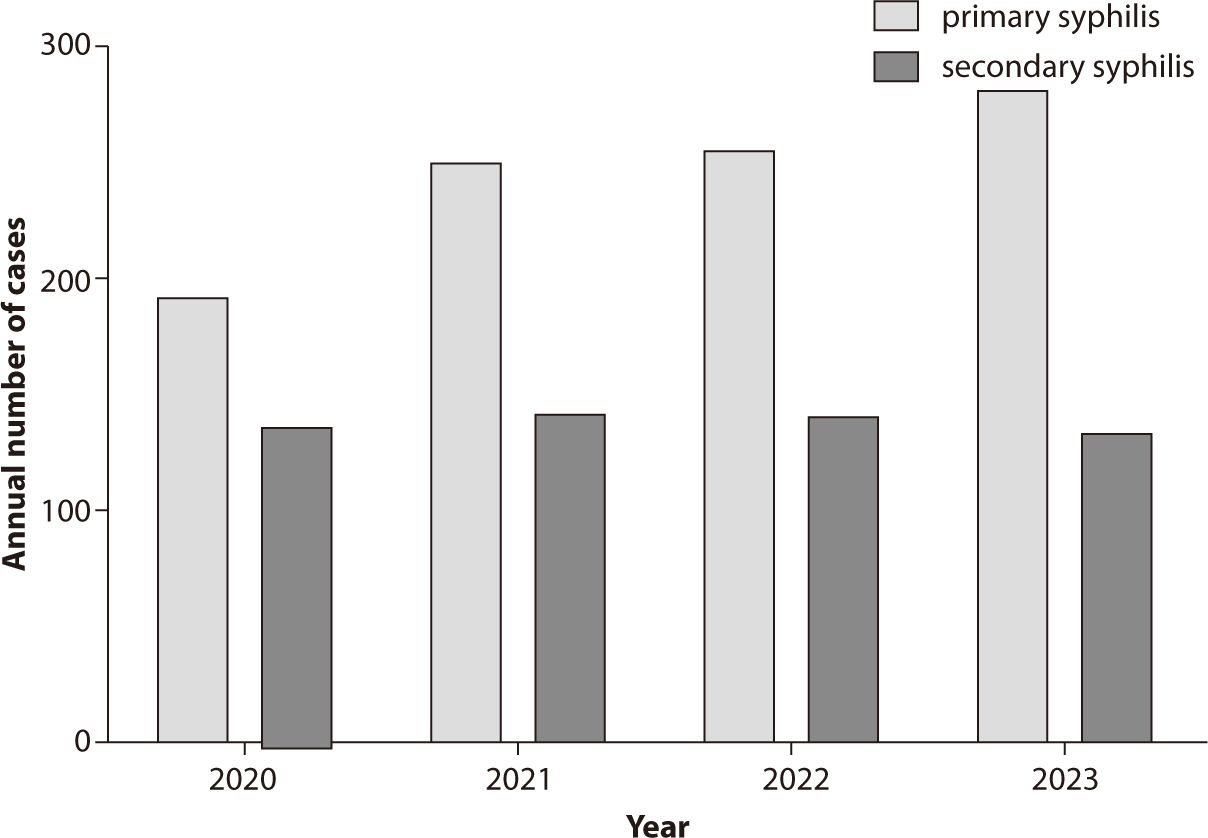

The prevalence of syphilis in Korea from 2017 to 2020 is detailed below. In 2019,

comprehensive surveillance identified 1,750 syphilis cases, with 1,276 cases

(72.9%) occurring in males and 474 cases (27.1%) in females. The age group of

20–40 years had the highest incidence, with 1,281 cases (73.2%), while

those aged 60 and older accounted for 192 cases (11.0%). Regarding the stage of

the disease, there were 1,176 cases of primary syphilis, 554 cases of secondary

syphilis, and 23 cases of congenital syphilis. After shifting to sentinel

surveillance in 2020, a total of 330 cases were reported, comprising 228 cases

(69.1%) in males and 102 cases (30.9%) in females. The 20–40 age group

represented 251 cases (76.1%), and the 60 and older age group had 30 cases

(9.1%). The breakdown by stage included 191 cases of primary syphilis, 136 cases

of secondary syphilis, and 3 cases of congenital syphilis. These data were

sourced from the Weekly Health and Disease Report of the Korea Disease Control

and Prevention Agency. Since the transition to sentinel surveillance in 2021,

there has been a noticeable change in the number of reported cases. From 2020 to

2023, the reported cases of primary syphilis were 191, 248, 254, and 280,

respectively, while secondary syphilis cases were 136, 140, 138, and 131 for the

same years (Fig. 1). Starting in 2024, with

the resumption of full-scale surveillance, it will be possible to compare these

figures with previous data. Fig. 1 also

presents a detailed breakdown of the number of cases for each stage of

syphilis.

Syphilis is primarily transmitted through sexual contact or from an infected

mother to her child during pregnancy. This disease is caused by the spirochete

Treponema pallidum. Although less common, transmission can

also occur through blood transfusions or organ transplants. Additionally, there

is a minimal risk of transmission through needlestick injuries in certain stages

of the disease [12].

The clinical presentation of syphilis can be broadly divided into symptomatic

periods and asymptomatic latent syphilis periods. The clinical course of

syphilis is categorized into symptomatic phases and periods of asymptomatic

latent syphilis. The symptomatic stages include primary, secondary, and tertiary

syphilis, with periods of latent syphilis occurring between these stages.

Primary syphilis, the initial stage of infection, typically presents as a single

painless ulcer, known as a chancre, at the site of T. pallidum

entry. This sore usually appears within 9 to 90 days after exposure and may be

accompanied by localized swelling of lymph nodes. While the ulcer is generally

painless, it can occasionally be painful. The ulcer characteristic of primary

syphilis typically heals spontaneously.

Secondary syphilis typically develops 4–10 weeks after the appearance of

the primary lesion and can affect the entire body. The symptoms of secondary

syphilis are diverse, with a characteristic rash being a common feature. This

rash, frequently involving the palms and soles, is observed in 48%–70% of

patients with secondary syphilis. Other manifestations may include abdominal

pain, hepatitis, pulmonary nodules, and alopecia. Additionally, condyloma lata,

presenting as wart-like lesions, may also occur. Although many patients receive

treatment during the secondary stage, the condition might resolve on its own

without antibiotics; however, if left untreated, it can progress to latent

syphilis. During this stage, the bacteria may infiltrate the central nervous

system, potentially leading to meningitis. Approximately 70% of cases of

untreated or latent syphilis remain symptom-free, but some may advance to

tertiary syphilis. Tertiary syphilis can involve cardiovascular syphilis,

neurosyphilis, and gummatous syphilis. Neurosyphilis is divided into two primary

forms: meningeal neurosyphilis, which can present with cranial nerve

dysfunction, meningitis, stroke, and changes in hearing or vision, and tabes

dorsalis, characterized by demyelination of the dorsal columns and associated

with ataxia, diminished reflexes, impaired proprioception, neuropathic pain, and

paralysis. Typically, neurosyphilis develops 10–30 years after the

initial infection [13].

Diagnosing syphilis is complex. The most definitive method involves direct

evidence of the syphilis bacterium. However, because Treponema

is difficult to culture, a culture-based diagnosis is not feasible. Although

dark-field microscopy can visualize Treponema from lesion

samples, this method is rarely used today. In cases of primary syphilis, samples

from chancres can be tested using PCR or other nucleic acid amplification tests

(NAATs) to detect Treponema. Additionally, multiplex PCR tests,

which diagnose multiple STIs simultaneously, can also detect syphilis from urine

samples.

However, in cases of secondary, tertiary, and latent syphilis, it is not feasible

to obtain samples that confirm the presence of the pathogen. Therefore, the

diagnosis relies on a combination of tests. For initial screening,

non-treponemal tests such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratories test or

the rapid plasma reagin test are employed. If these tests yield positive

results, confirmation is sought through treponemal tests, including the

T. pallidum latex agglutination, T.

pallidum hemagglutination assay, or the fluorescent treponemal

antibody absorption immunoglobulin test.

Both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021 treatment guidelines and

Korea's 2023 treatment guidelines recommend the same treatment [2]. Penicillin injections are the first-line

treatment for syphilis at all stages [14]. Benzathine penicillin G is the drug of choice for all cases except

neurosyphilis. Thanks to its depot effect, it can be administered once a week.

Benzathine penicillin G must be given intramuscularly, not intravenously. For

primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis, a single dose of 2.4 million

units of benzathine penicillin G is administered. For late latent syphilis, 2.4

million units are administered weekly for three weeks. Alternatively,

doxycycline 100 mg taken twice daily for 14–28 days can be used, but it

is contraindicated during pregnancy, where penicillin is the only option.

A characteristic reaction known as the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction may occur

following the treatment of spirochetal infections, including syphilis [15]. This inflammatory response is

triggered by the release of cytokines and typically manifests within 24 hours of

treatment, presenting symptoms such as myalgia and fever.

Go to :

Gonorrhea, similar to syphilis, is one of the oldest known STIs. The systematic

recording and management of gonorrhea in Korea commenced during the Japanese

colonial period and persisted through the American military government period

following liberation. Since that time, reports on domestic prevalence and antibiotic

susceptibility have been published [16].

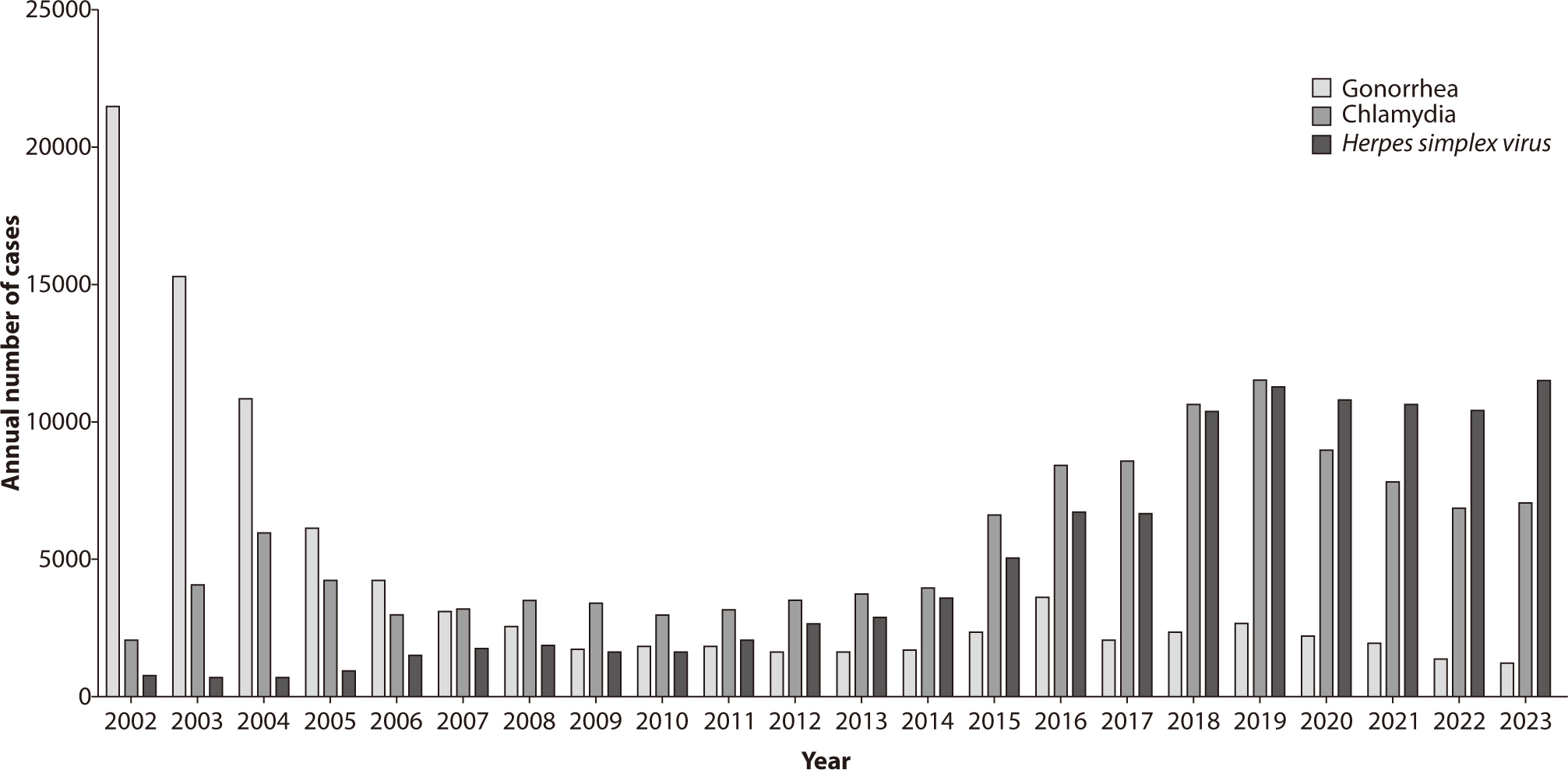

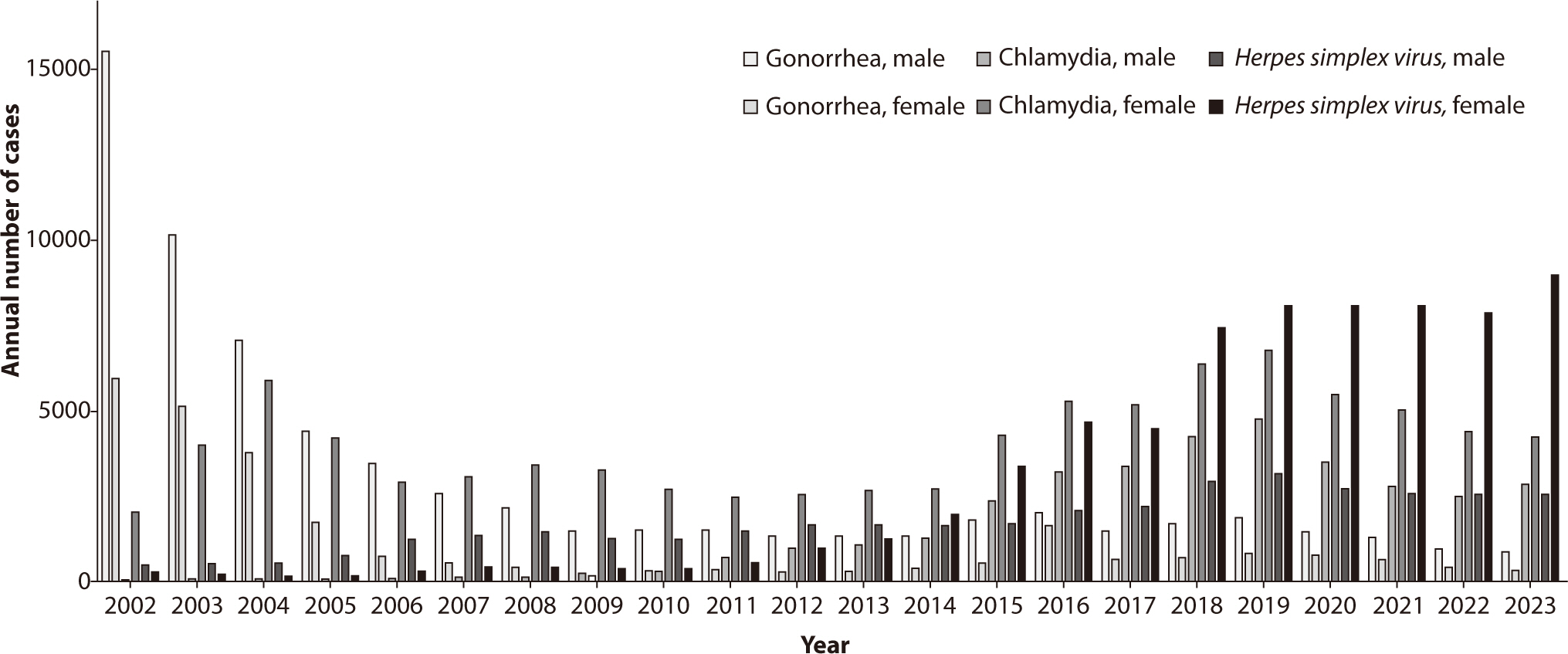

The annual incidence of gonorrhea in Korea is shown in Figs. 2, 3. In 2023,

sentinel surveillance reported 1,204 cases of gonorrhea, indicating a decreasing

trend in its incidence. A particularly concerning issue is the antibiotic

resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the bacterium responsible

for gonorrhea. There has been a significant global increase in resistance to

fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, and a rising trend in resistance to

azithromycin [17]. Additionally, strains

resistant to ceftriaxone, considered a last-resort treatment for gonorrhea, have

recently been identified, particularly in countries such as the United Kingdom

and Japan. Extensively drug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae has also

emerged, leading to treatment failures with the combined therapy of ceftriaxone

and azithromycin [18–20]. In Korea, the antibiotic resistance

rates of N. gonorrhoeae have shown concerning trends:

resistance to ciprofloxacin increased from 26% in 2000 to 83% in 2006 among

strains collected during that period. During the same timeframe, no resistance

to ceftriaxone or cefixime was reported. Resistance to tetracycline was noted to

be between 93%–100% [21]. From

data collected between 2011 and 2013, 3% of the strains were resistant to

ceftriaxone, 9% to cefixime, 38% showed intermediate resistance or resistance to

azithromycin, and 97% were resistant to ciprofloxacin [22]. Antibiotic resistance testing on N.

gonorrhoeae conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention from 2013 to 2015 indicated that almost no strains were susceptible

to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline. While susceptibility to ceftriaxone and

cefixime was still maintained, resistance to cefixime showed an increasing

trend. Furthermore, there was an upward trend in the number of strains

exhibiting simultaneous resistance to multiple antibiotics from 2013 to

2015.

Gonorrhea can result in infections in the urogenital tract, oropharynx, and

rectum. It can also cause bacteremia, which may manifest with skin lesions or

arthritis. In women, between 86.4% and 92.6% of urogenital infections caused by

gonorrhea are asymptomatic [23]. Although

less precisely determined, a population-based multicenter study with 11,408

participants found that 55.7% to 86.8% of urogenital infections in men were

asymptomatic [13,23].

The most common symptom of a gonorrhea infection is gonococcal urethritis, which

typically manifests in men as urethral discharge and dysuria following an

incubation period of 2 to 8 days. In women who exhibit symptoms, the infection

may lead to vaginal discharge, itching, intermenstrual bleeding, or heavy

menstrual periods. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) associated with gonorrhea

can cause symptoms such as abdominal pain or pain during intercourse. Gonococcal

pharyngitis may present with a sore throat, pharyngeal exudates, or swollen

cervical lymph nodes, whereas gonococcal proctitis can lead to anorectal pain, a

sensation of incomplete bowel evacuation, bleeding, or mucoid discharge. In

Korea, cases of disseminated gonococcal infection have been reported, presenting

as bacteremia and liver abscesses [24].

The typical presentation of disseminated gonococcal infection includes purulent

arthritis, polyarthralgia, tenosynovitis, and skin rashes [25].

The diagnosis of gonorrhea involves identifying N. gonorrhoeae

from the infected site. Traditionally, bacterial culture was the primary method

used; however, NAATs have now become widely employed. Nevertheless, to determine

antibiotic resistance, obtaining the pathogen through culture is necessary.

Therefore, it is recommended to perform bacterial culture alongside NAATs when

diagnosing gonorrhea. In men, first-void urine is commonly tested, and urethral

swab tests are also an option. In women, vaginal swab tests are primarily used,

although cervical swabs can also be taken. Recently, the use of self-collected

samples has been introduced. The sensitivity of culture for detecting gonorrhea

ranges from 50% to 85%, with lower sensitivity observed in non-genital sites and

among asymptomatic patients [26].

The treatment guidelines for gonorrhea are regularly updated. The most recent

guidelines from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),

issued in 2021, recommend a single intramuscular dose of 500 mg of ceftriaxone

for uncomplicated gonorrhea [2].

Additionally, if a chlamydial infection cannot be ruled out, administering

doxycycline (100 mg) twice daily for 7 days is advised. There are notable

differences between the U.S. and European guidelines, especially concerning the

use of dual therapy [4]. While previous

U.S. guidelines favored dual therapy, the current recommendations support

monotherapy. The 2023 domestic guidelines also endorse a single intramuscular or

intravenous dose of 500 mg ceftriaxone for uncomplicated urogenital, cervical,

and rectal gonococcal infections in adults. Alternative treatments include a

single intramuscular dose of 2 g of spectinomycin or a combination therapy

consisting of 240 mg of intramuscular gentamicin and 2 g of oral azithromycin.

For pharyngeal infections, however, both the U.S. and domestic guidelines

continue to recommend a single intramuscular dose of 500 mg of ceftriaxone.

Go to :

Chlamydia is an infection caused by serovars D through K of Chlamydia

trachomatis. Previously, it was often categorized with other infections

such as non-gonococcal urethritis. However, it is now recognized as one of the most

prevalent STIs. In the United States, data from 2019 reported 1,808,703 new cases,

making chlamydia the most commonly reported STI [27]. In Korea, surveillance data indicated an increasing incidence of

chlamydia infections until 2019, with 11,518 cases reported that year. Following the

COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, however, the number of reported cases declined to 7,064

in 2023 (Figs. 2, 3). This decrease may be attributed to factors such as reduced testing

and healthcare access during the pandemic, changes in sexual behavior, or the

reprioritization of healthcare resources. These factors have been noted in various

international studies, although it was challenging to confirm with domestic data.

Nonetheless, it is believed that the situation in the country would not have been

significantly different.

Chlamydia can lead to urogenital, oropharyngeal, rectal, and ocular infections in

both men and women. The majority of these cases are asymptomatic, with over 70%

of urogenital infections in women and more than 80% in men presenting no

symptoms. Similarly, around 90% of rectal and pharyngeal infections remain

asymptomatic [28]. When symptoms do

occur, chlamydia infections typically manifest as urethritis, characterized by

dysuria and urethral discharge, cervicitis, PID, and proctitis, which includes

pain, discharge, and bleeding. In men, the infection may also lead to

epididymitis. Additionally, chlamydia can cause Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome, a

specific form of PID.

In neonates born vaginally to mothers with chlamydia, there is a risk of

developing conjunctivitis or pneumonia. Additionally, a rare manifestation of

chlamydia infection, known as lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), may also occur.

LGV progresses through three stages: initially, a small, painless, temporary

ulcer appears at the infection site. The second stage, which develops 2 to 6

weeks later, is marked by large, painful inguinal lymph nodes, with

approximately 30% of these nodes spontaneously rupturing. If left untreated, the

third stage involves chronic lymphadenitis, which leads to scarring, lymphedema,

and genital elephantiasis [29].

Chlamydia is diagnosed by detecting the pathogen with NAATs from the suspected

site of infection. The process for collecting samples is similar to that used

for gonorrhea; however, since cultures are not conducted, NAATs are the sole

diagnostic method employed.

The treatment for chlamydia is doxycycline. According to the updated 2021

guidelines from the U.S. CDC, doxycycline is now recommended as the first-line

treatment [2], a decision supported by

recent studies [30–32]. Domestic guidelines also endorse

doxycycline, prescribing 100 mg twice daily for 7 days. Alternative treatments

include azithromycin (1 g) or levofloxacin (500 mg), both administered for 7

days. A study conducted in Japan revealed that the antibiotic resistance rates

for C. trachomatis were 2.0% for azithromycin and 2.4% for

clarithromycin [33].

Go to :

M. genitalium was not widely recognized as an infection in the past,

but it has recently gained attention as a STI. In the 2015 guidelines from the U.S.

CDC, M. genitalium was described as an "emerging pathogen of

uncertain significance" [34]. However,

with the accumulation of more data, recent guidelines now recommend treatment for it

[2].

Since M. genitalium is not a notifiable infection in Korea,

nationwide incidence statistics are not compiled. A study conducted in Korea

between 2012 and 2015 involving 14,932 soldiers with urological symptoms found

that chlamydia was the most prevalent infection at 36.6%, followed by

Ureaplasma urealyticum at 24.0%, and M.

genitalium at 21.5%. N. gonorrhoeae accounted for

19.0% of the cases [35]. Another study,

carried out from 2018 to 2020 on outpatients, identified M.

genitalium in 3.27% of the cases, with the highest prevalence

observed in the 20–29 age group [36].

The urogenital tract is the primary site of M. genitalium

infection, although it can also occasionally cause proctitis. In cases of

recurrent and persistent urethritis, M. genitalium is detected

in approximately 30%–40% of instances. Although M.

genitalium often remains asymptomatic, it is present in

30%–40% of men with persistent recurrent urethritis [37]. Symptoms during these episodes

typically include dysuria and urethral discomfort. In women, M.

genitalium is associated with cervicitis, PID, and infertility. The

main symptoms in women are those related to cervicitis, such as post-coital

bleeding, intermenstrual bleeding, and lower abdominal pain [38].

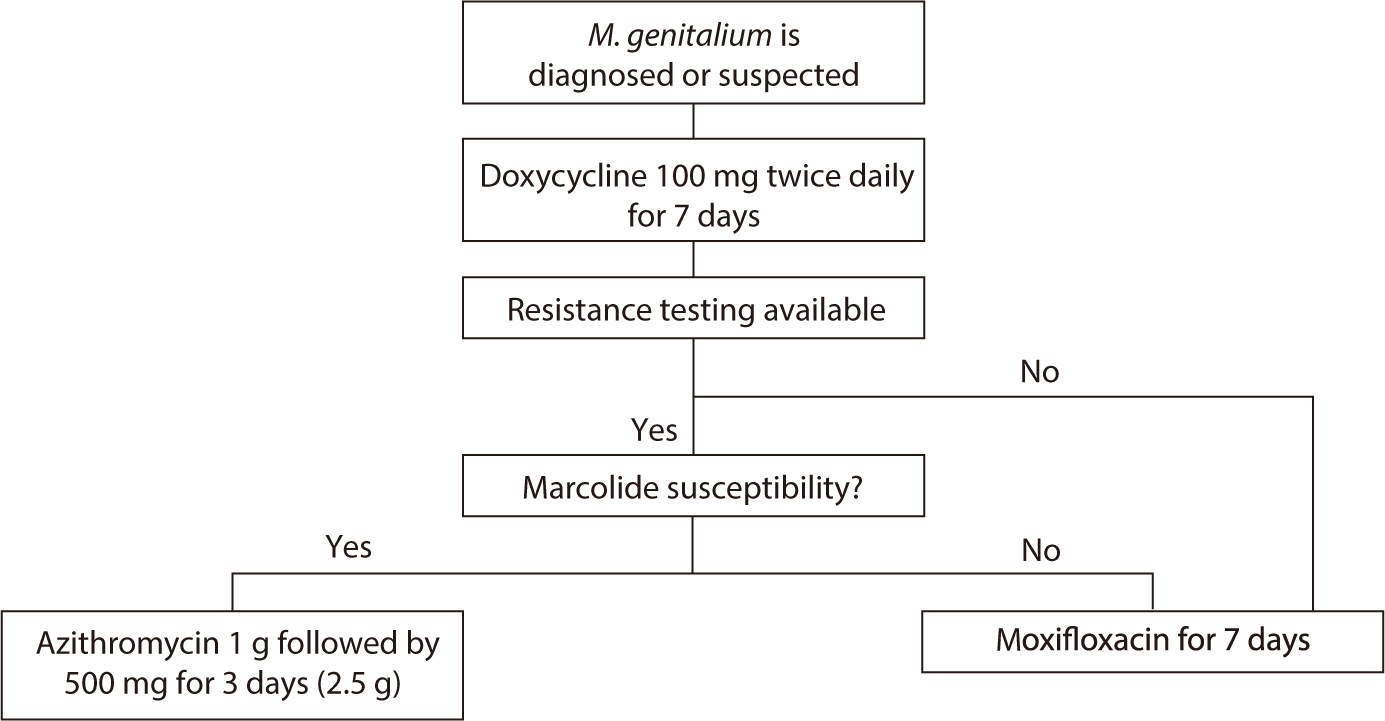

M. genitalium often fails to respond to treatment, primarily due

to resistance to the medications used. Therefore, recent major guidelines

recommend assessing resistance before selecting a treatment regimen for

M. genitalium [2].

However, since macrolide resistance testing tools are not yet available

domestically, these recommendations cannot be applied in the local context

(Fig. 4).

If resistance testing is possible, administer doxycycline (100 mg) twice daily

for 7 days initially. If the organism is susceptible to macrolides, azithromycin

can be administered as a single 1 g oral dose followed by three additional 500

mg doses (totaling 2.5 g). In the presence of macrolide resistance, moxifloxacin

(400 mg) taken orally for 7 days is recommended. If resistance testing is not

available, the recommended approach is to administer doxycycline for one week

followed by moxifloxacin for another week. The 2023 domestic guidelines suggest

starting treatment with azithromycin (500 mg orally), followed by 250 mg daily

for 4 days (total 1.5 g). In cases of treatment failure or recurrence, a 7-day

course of doxycycline or minocycline is advised, followed by further treatment

decisions based on macrolide susceptibility. If testing is not feasible or if

macrolide susceptibility is confirmed, the recommended regimen is 1 g of

azithromycin followed by 500 mg daily for 3 days (total 2.5 g), with a follow-up

at 21 days to confirm cure. If macrolide resistance is detected, a 7-day course

of moxifloxacin 400 mg is recommended.

Go to :

HSV is categorized into type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2), both of which can

cause genital herpes [39]. However, HSV-2

is primarily associated with anogenital herpes, whereas HSV-1 typically leads to

cold sores around the lips. In Korea, the incidence of HSV-2 is monitored

through a sample surveillance system. Data show that there were 6,657 cases in

2017, 10,347 cases in 2018, 11,229 cases in 2019, 10,759 cases in 2020, 10,637

cases in 2021, 10,403 cases in 2022, and 11,449 cases in 2023. Additionally, the

number of cases reported per institution has been steadily increasing (Figs. 2, 3).

Most individuals infected with HSV remain asymptomatic, and the majority are

unaware that they are carriers. During the initial infection, which follows an

incubation period of approximately 4–7 days post-contact, patients

develop multiple painful, bilateral, erythematous lesions. These lesions

progress through stages including papules, vesicles, and ulcers, and typically

last between 16.5 to 19.7 days [13,40]. Additionally, 39%–68% of

patients report experiencing headaches, fever, and lymphadenopathy during this

initial phase [13]. Following the initial

outbreak, the virus enters a latent state where it remains asymptomatic.

Symptomatic recurrences occur in about 40-50% of cases and are often preceded by

prodromal symptoms localized to the affected area. These symptoms, which include

itching or burning sensations, help patients recognize the onset of a new

outbreak. Recurrences tend to be milder than the initial infection and usually

resolve within 5–10 days.

Testing for HSV can be performed on samples from vesicular lesions using NAATs,

such as PCR, which have very high sensitivity. A wet swab is the preferred

method, but a dry swab can also be used. While viral culture is an option, it is

less sensitive and more time-consuming than NAAT, and thus, it is not

recommended as the sole testing method. Viral culture may be utilized in

instances where the infection does not respond to treatment or antiviral

resistance is suspected. Serological testing is valuable for identifying

infections, especially latent infections in the absence of skin lesions, and is

frequently employed in demographic studies.

Treatment for HSV includes oral or injectable antiviral medications. The primary

antiviral drugs used are acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir. Although

these medications do not cure HSV, they help reduce symptoms, shorten the

duration of the disease, and decrease the recurrence rate. Despite the

availability of various antiviral drugs, most share similar mechanisms of action

and efficacy. For suspected initial infections, a 10-day course of antiviral

treatment is recommended, which may be extended by an additional week if lesions

persist. For recurrent lesions, a shorter course of treatment may be attempted.

Topical antiviral treatment alone is not recommended due to its insufficient

effectiveness.

Go to :

This review highlights the evolving landscape of STIs in Korea. The COVID-19 pandemic

has significantly impacted the epidemiology of STIs, necessitating adaptations in

healthcare delivery and public health strategies. The emergence of

antibiotic-resistant strains, particularly in gonorrhea and M.

genitalium, underscores the importance of antimicrobial stewardship and

the development of new therapeutic options. Continuing efforts in education,

prevention, and research are essential to manage and mitigate the impact of STIs on

public health.

Go to :

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Sexually transmitted infections national strategic plan for the United

States: 2021–2025. Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services;2020.

2. Workowski KA. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines,

2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021; 70(4):1–187. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1. PMID: 34292926. PMCID: PMC8344968.

3. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the management of symptomatic sexually transmitted

infections. Geneva: World Health Organization;2021.

4. Gamoudi D, Flew S, Cusini M, Benardon S, Poder A, Radcliffe K. 2018 European guideline on the organization of a consultation for

sexually transmitted infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019; 33(8):1452–1458. DOI: 10.1111/jdv.15577. PMID: 30968975.

5. Wood GE, Bradshaw CS, Manhart LE. Update in epidemiology and management of Mycoplasma

genitalium infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2023; 37(2):311–333. DOI: 10.1016/j.idc.2023.02.009. PMID: 37105645.

6. Lee J, Kim Y, Choi JY. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV services in Korea: results

from a cross-sectional online survey. Infect Chemother. 2021; 53(4):741–752. DOI: 10.3947/ic.2021.0112. PMID: 34979605. PMCID: PMC8731254.

7. Seong H, Choi Y, Ahn KH, Choi JY, Kim SW, Kim SI, et al. Assessment of disease burden and immunization rates for

vaccine-preventable diseases in people living with HIV: the Korea HIV/AIDS

cohort study. Infect Chemother. 2023; 55(4):441–450. DOI: 10.3947/ic.2023.0045. PMID: 37674339. PMCID: PMC10771952.

8. Lee M, Park WB, Kim ES, Kim Y, Park SW, Lee E, et al. Possibility of decreasing incidence of human immunodeficiency

virus infection in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2023; 55(4):451–459. DOI: 10.3947/ic.2023.0056. PMID: 37674340. PMCID: PMC10771950.

9. Park JK, Shin YS. Risk factors for urethral condyloma among heterosexual young male

patients with condyloma acuminatum of penile skin. Infect Chemother. 2016; 48(3):216–218. DOI: 10.3947/ic.2016.48.3.216. PMID: 27659432. PMCID: PMC5048003.

10. Rothschild BM. History of syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 40(10):1454–1463. DOI: 10.1086/429626. PMID: 15844068.

11. Wang S, Kim S, Cho S, Kim HS, Min S. Introduction to the transition of mandatory surveillance system

in the syphilis monitoring. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2023; 16(47):1620–1630. DOI: 10.56786/PHWR.2023.16.47.3.

12. Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(9):845–854. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1901593. PMID: 32101666.

13. Tuddenham S, Hamill MM, Ghanem KG. Diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections: a

review. JAMA. 2022; 327(2):161–172. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2021.23487. PMID: 35015033.

14. Clement ME, Okeke NL, Hicks CB. Treatment of syphilis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014; 312(18):1905–1917. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2014.13259. PMID: 25387188. PMCID: PMC6690208.

15. Butler T. The Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction after antibiotic treatment

of spirochetal infections: a review of recent cases and our understanding of

pathogenesis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017; 96(1):46–52. DOI: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0434. PMID: 28077740. PMCID: PMC5239707.

16. Choi JK, Lee SJ, Yoo JH. History of syphilis and gonorrhea in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2019; 51(2):210–216. DOI: 10.3947/ic.2019.51.2.210. PMID: 31271002. PMCID: PMC6609744.

17. Unemo M, Lahra MM, Escher M, Eremin S, Cole MJ, Galarza P, et al. WHO global antimicrobial resistance surveillance for

Neisseria gonorrhoeae 2017–18: a retrospective

observational study. Lancet Microbe. 2021; 2(11):E627–E636. DOI: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00171-3. PMID: 35544082.

18. Kueakulpattana N, Wannigama DL, Luk-in S, Hongsing P, Hurst C, Badavath VN, et al. Multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae

infection in heterosexual men with reduced susceptibility to ceftriaxone,

first report in Thailand. Sci Rep. 2021; 11(1):21659. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-00675-y. PMID: 34737332. PMCID: PMC8569152.

19. Pleininger S, Indra A, Golparian D, Heger F, Schindler S, Jacobsson S, et al. Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Neisseria

gonorrhoeae causing possible gonorrhoea treatment failure with

ceftriaxone plus azithromycin in Austria, April 2022. Eurosurveill. 2022; 27(24):2200455. DOI: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.24.2200455. PMID: 35713023. PMCID: PMC9205165.

20. Yun IJ, Park HJ, Chae J, Heo SJ, Kim YC, Kim B, et al. Nationwide analysis of antimicrobial prescription in Korean

hospitals between 2018 and 2021: the 2023 KONAS report. Infect Chemother. 2024; 56(2):256–265. DOI: 10.3947/ic.2024.0013. PMID: 38960739. PMCID: PMC11224044.

21. Lee H, Hong SG, Soe Y, Yong D, Jeong SH, Lee K, et al. Trends in antimicrobial resistance of Neisseria

gonorrhoeae isolated from Korean patients from 2000 to

2006. Sex Transm Dis. 2011; 38(11):1082–1086. DOI: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31822e60a4. PMID: 21992988.

22. Lee H, Unemo M, Kim HJ, Seo Y, Lee K, Chong Y. Emergence of decreased susceptibility and resistance to

extended-spectrum cephalosporins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae

in Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015; 70(9):2536–2542. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkv146. PMID: 26084303. PMCID: PMC4539094.

23. Detels R, Green AM, Klausner JD, Katzenstein D, Gaydos C, Handsfield H, et al. The incidence and correlates of symptomatic and asymptomatic

Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria

gonorrhoeae infections in selected populations in five

countries. Sex Transm Dis. 2011; 38(6):503–509. DOI: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318206c288. PMID: 22256336. PMCID: PMC3408314.

24. Lee MH, Byun J, Jung M, Yang JJ, Park KH, Moon S, et al. Disseminated gonococcal infection presenting as bacteremia and

liver abscesses in a healthy adult. Infect Chemother. 2015; 47(1):60–63. DOI: 10.3947/ic.2015.47.1.60. PMID: 25844265. PMCID: PMC4384456.

25. Nettleton WD, Kent JB, Macomber K, Brandt MG, Jones K, Ridpath AD, et al. Notes from the field: ongoing cluster of highly related

disseminated gonococcal infections: Southwest Michigan, 2019. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69(12):353–354. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912a5. PMID: 32214085. PMCID: PMC7725508.

26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of

Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria

gonorrhoeae: 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014; 63(RR02):1–19.

27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services;2019.

28. Chan PA, Robinette A, Montgomery M, Almonte A, Cu-Uvin S, Lonks JR, et al. Extragenital infections caused by Chlamydia

trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a

review of the literature. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2016; 2016(1):5758387. DOI: 10.1155/2016/5758387. PMID: 27366021. PMCID: PMC4913006.

29. Stoner BP, Cohen SE. Lymphogranuloma venereum 2015: clinical presentation, diagnosis,

and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2015; 61(suppl_8):S865–S873. DOI: 10.1093/cid/civ756. PMID: 26602624.

30. Geisler WM, Uniyal A, Lee JY, Lensing SY, Johnson S, Perry RCW, et al. Azithromycin versus doxycycline for urogenital chlamydia

trachomatis infection. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373(26):2512–2521. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502599. PMID: 26699167. PMCID: PMC4708266.

31. Dombrowski JC, Wierzbicki MR, Newman LM, Powell JA, Miller A, Dithmer D, et al. Doxycycline versus azithromycin for the treatment of rectal

chlamydia in men who have sex with men: a randomized controlled

trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021; 73(5):824–831. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciab153. PMID: 33606009. PMCID: PMC8571563.

32. Lau A, Kong FYS, Fairley CK, Templeton DJ, Amin J, Phillips S, et al. Azithromycin or doxycycline for asymptomatic rectal

Chlamydia trachomatis. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384(25):2418–2427. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031631. PMID: 34161706.

33. Suzuki S, Hoshi S, Sagara Y, Sekizawa A, Kinoshita K, Kitamura T. Antimicrobial resistance for Chlamydia

trachomatis genital infection during pregnancy in

Japan. Infect Chemother. 2022; 54(1):173–175. DOI: 10.3947/ic.2022.0030. PMID: 35384428. PMCID: PMC8987183.

34. Workowski KA. Centers for disease control and prevention sexually transmitted

diseases treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2015; 61(suppl_8):S759–S762. DOI: 10.1093/cid/civ771. PMID: 26602614.

35. Kim HJ, Park JK, Park SC, Kim YG, Choi H, Ko JI, et al. The prevalence of causative organisms of community-acquired

urethritis in an age group at high risk for sexually transmitted infections

in Korean soldiers. BMJ Mil Health. 2017; 163(1):20–22. DOI: 10.1136/jramc-2015-000488. PMID: 26607860.

36. Oh EJ, Jang TS, Kim JK. Mycoplasma genitalium and Mycoplasma

hominis infection in South Korea during

2018-2020. Iran J Microbiol. 2021; 13(5):602–607. DOI: 10.18502/ijm.v13i5.7423. PMID: 34900157. PMCID: PMC8629812.

37. Seña AC, Lensing S, Rompalo A, Taylor SN, Martin DH, Lopez LM, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium,

and Trichomonas vaginalis infections in men with

nongonococcal urethritis: predictors and persistence after

therapy. J Infect Dis. 2012; 206(3):357–365. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/jis356. PMID: 22615318. PMCID: PMC3490700.

38. Soni S, Horner P, Rayment M, Pinto-Sander N, Naous N, Parkhouse A, et al. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV national guideline

for the management of infection with Mycoplasma genitalium

(2018). Int J STD AIDS. 2019; 30(10):938–950. DOI: 10.1177/0956462419825948. PMID: 31280688.

39. Gnann JW Jr, Whitley RJ. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2016; 375(19):1906. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc1611877.

40. Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, Holmes KK. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations,

course, and complications. Ann Intern Med. 1983; 98(6):958–972. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-6-958. PMID: 6344712.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download