INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common and aggressive primary intracranial malignancy in adults [

1]. Despite receiving standard of care treatment (maximal safe resection followed by chemoradiation), patients diagnosed with GBM have a median survival of approximately 15 months [

2]. In approximately two-thirds of cases, recurrence of GBM is seen within 2 cm from the margins of the primary tumor, with the remaining one-third of cases recurring distal to the initial tumor site [

3]. These sites of distant recurrence can include the ipsilateral lobe, the contralateral hemisphere, and infratentorial regions [

3]. Glioma cell migration via myelinated white matter tracts is a hypothesized mechanism of intracranial seeding and catalyst for recurrence [

4]. However, in these cases, T2-weighted MRI typically demonstrates a fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal, indicating white matter disease spread [

4]. This report describes an unusual case of a 31-year-old male patient with a recurrent distant GBM in the contralateral hemisphere encompassing a preexisting ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheter. The second lesion shared a genetic profile with the previously diagnosed glioblastoma, despite a lack of FLAIR signal abnormality in the intervening white matter, possibly suggesting an alternate mechanism of GBM recurrence undescribed in the literature.

CASE REPORT

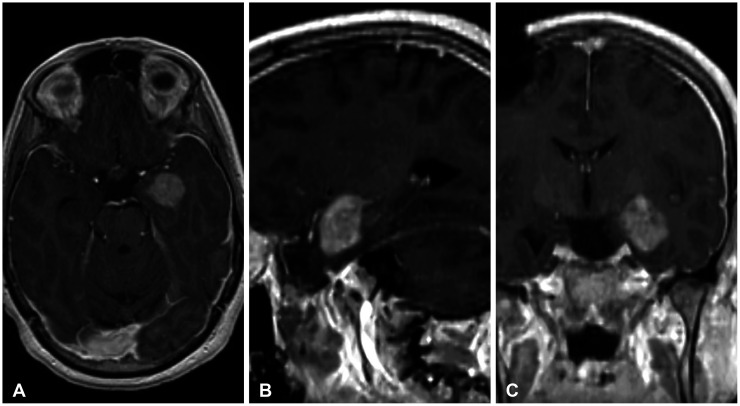

A 31-year-old right-handed male patient with a history of cervicomedullary junction (CMJ) astrocytoma as a child and a resected glioblastoma 2 years prior presented with a new enhancing lesion around an existing ventriculoperitoneal catheter on serial imaging. At the age of 8, the patient was diagnosed with a CMJ astrocytoma which was resected, and a right-sided ventriculoperitoneal shunt was placed. Following resection, the patient continued to demonstrate progression of disease for which he underwent chemotherapy along with whole brain and spine radiation after which imaging demonstrated tumor regression. Twenty years later, the patient presented with a tonic-clonic seizure. Imaging demonstrated a 2 cm diffusely enhancing left medial temporal lobe lesion for which he underwent a left frontotemporal craniotomy for gross total resection (

Fig. 1). Surgical pathology revealed glioblastoma, genetically characterized as

IDH-wildtype with

MGMT promoter methylation. Next-generation sequencing (GlioSeq™ panel) revealed biallelic

CDKN2A/B copy number loss as well as other copy number changes. Interestingly, sequencing demonstrated an absence of common adult GBM mutations such as

TERT mutation and

EGFR amplification. The patient underwent concomitant radiotherapy and four cycles of chemotherapy before electively stopping.

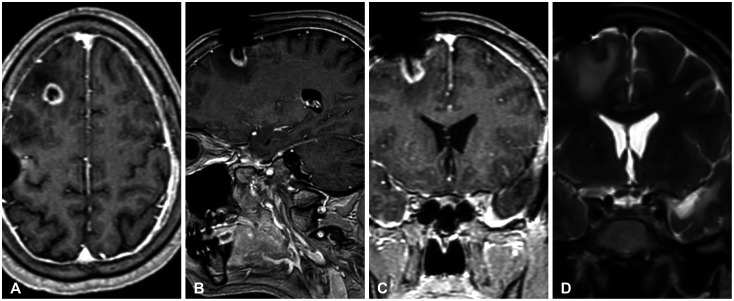

Two years later, the patient was found to have a 1.5 cm ring-enhancing right frontal lesion encompassing his shunt directly beneath the cortical surface. MRI demonstrated a lack of FLAIR signaling between the new right-sided frontal lobe lesion and the left temporal lesion (

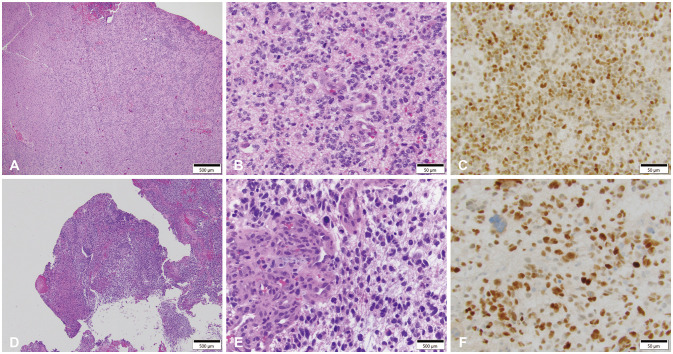

Fig. 2). The patient underwent a right frontal craniotomy with gross total resection and his frontal shunt was converted to a right parietal shunt. Histological analysis revealed glioblastoma (

Fig. 3) and GlioSeq™ analysis revealed a similar genetic profile as seen in the prior contralateral tumor, with the addition of a newly acquired

TP53 mutation (P250L). Concordant with the

TP53 mutation, the recurrent tumor showed stronger nuclear reactivity for p53 by immunohistochemical staining (

Fig. 3C and F). The patient has since made a complete recovery following completion of radiotherapy.

DISCUSSION

For patients diagnosed with GBM, recurrence of treated disease remains the largest cause of morbidity and mortality [

35]. Despite advances in GBM tumor biology, the mechanistic drivers of GBM recurrence still evade elucidation and are an area of ongoing investigation [

35]. It is known, however, that glioma cells primarily migrate through the perivascular space and brain parenchyma [

6]. Recurrence of GBM can be categorized as distant or local [

3] with two-thirds of all GBM recurrences being “local”(occurring within 2 centimeters of the margins of the primary tumor). The remaining one-third of recurrences are classified as “distant” [

3], which can occur ipsilaterally in a different region or lobe, infratentorially, or in the contralateral hemisphere [

3]. Interestingly, Kim et al. [

6] demonstrate a correlation between distant GBM recurrence and low mutation retention ratio. Further, they demonstrated that locally recurring GBM showed, on average, 70% mutation retention compared to only 25% in distantly recurring tumors [

6]. While differences in the mutational profiles of primary and recurrent GBM may imply emergence of a

de novo lesion, this assumption is challenged by the hypothesis that genetic differences can be attributed to the DNA damaging effects of radiation therapy and selection pressures following immunotherapy. Pre-resection migration and subsequent transient dormancy of glioma cells may also explain genetic differences seen in distant recurrence [

36]. Though genetic markers alone cannot differentiate

de novo GBM from recurrence, the mutation retention ratio may be useful in prompting further investigation.

In this novel report, an unusual case of a genetically similar GBM recurrence is described more than 2 years after initial resection in the contralateral hemisphere encompassing the patient’s preexisting ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Notably, T2-weighted MRI (

Fig. 2) of the patient’s recurrence failed to demonstrate FLAIR signal abnormalities indicative of disease spread—a phenomenon convincingly described by Giese et al. [

4]. Giese et al. [

4] elucidated methods of glioma migration that were independent of the extracellular matrix proteins previously thought to be necessary for migration. Given their work, T2-FLAIR or diffusion weighted MRI (DWI) is a reliable method for assessing recurrence migration [

7]. While recurrence with no distinct white matter tractography is not uncommon, the localization of this recurrence at the site of a preexisting foreign body may suggest another driver of recurrence. Thus, this study considers the possibility that this patient’s recurrence results from chronic local inflammation due to the presence of the ventriculoperitoneal shunt. The relationship between chronic inflammation and oncogenesis has been established in several cancers [

89]. In such cancers, inflammation secondary to infection, autoimmune, or environmental irritants is thought to create reactive oxygen species that damage cells and, increase genetic alterations, promoting tumorigenesis [

9]. In this case, the patient’s shunt may have helped trigger gliomagenesis by inducing inflammation in the microenvironment secondary to local environmental microdamage, a phenomenon described by Ha et al. [

10] as a potential initiating event. Other case reports have shown GBM occurrences around intracranial hardware such as shunt catheters and deep brain stimulator leads; however, these reports describe instances of primary GBM [

1112]. Additionally, multiple studies and meta-analyses have correlated the use of anti-inflammatories with reduced risk of GBM development, further supporting inflammatory gliomagenesis [

13].

The unique nature of this case stems from several factors: first, this patient’s primary and recurrent GBM display largely shared genetic mutations; second, there is no clear radiologic evidence of his recurrence occurring along any identifiable white matter tract; and third, the atypical encompassing nature of the patient’s tumor around the shunt. We further hypothesize that migration of glioma cells from this patient’s primary tumor may have been the result of dissemination through the cerebrospinal fluid. Review of the literature documents multiple instances of glioma dissemination in the presence of an existing ventriculoperitoneal shunt [

111415]. However, nearly all of these documented cases describe instances of extracranial seeding. This study postulates that following seeding, an inflammatory microenvironment due to the shunt initiated the inflammatory cascade that altered the environment around the shunt to support tumorigenesis.

Recurrence of tumors is nearly inevitable in patients with glioblastoma. While cases of recurrence can be identified as local or distant, MRI scan and evaluation of genetic mutations may provide insight regarding whether the secondary lesion represents recurrence or a de novo tumor. In this report, we illustrate an atypical case in which a patient with a distant recurrence encompassing his ventriculoperitoneal shunt displays similar genetic mutations as his primary tumor, with no evidence of intervening white matter involvement. We, therefore, investigate the possible influence of his shunt and highlight the role inflammation can have on the development of recurrent GBM. The authors conclude that in extremely rare instances, foreign objects, such as shunts, can stimulate an inflammatory microenvironment, leading to initiation of tumorigenesis by activating dormant glioma cells.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download