Abstract

Toxocariasis, a zoonotic infection transmitted by Toxocara canis (from dogs) and Toxocara cati (from cats) larvae, poses rare but severe risks to humans. We present a case of hepatic visceral larva migrans (VLM) caused by Toxocara canis in a 21-year-old male with a history of close contact with a pet dog. Initial symptoms and imaging findings mimicked a pyogenic liver abscess. The initial laboratory investigations revealed neutrophilia and elevated levels of IgE. Despite broad-spectrum antibiotics, persistent fever prompted further investigation. Subsequent serological testing for Toxocara antibodies and histopathological analysis of liver tissue demonstrating eosinophil infiltrates and Charcot-Leyden crystals led to a confirmed diagnosis of a liver abscess caused by Toxocara canis. Serological testing for Toxocara antibodies and histopathological analysis of liver tissue confirmed a Toxocara canis-induced liver abscess. Albendazole treatment yielded significant clinical improvement. This case highlights the necessity of considering toxocariasis in liver abscess differentials, particularly in high-seroprevalence regions like Vietnam. Relying solely on serological tests may be insufficient, emphasizing the need for corroborative evidence, including invasive procedures like liver biopsy, for accurate hepatic toxocariasis diagnosis.

Toxocariasis is a parasitic zoonosis stemming from the eggs or larvae of Toxocara canis or, less commonly, Toxocara cati, typically found in dogs and cats. This infection manifests through three clinical syndromes: visceral larva migrans (VLM), ocular larva migrans, and covert toxocariasis. VLM, a systemic condition, exhibits symptoms like fever, abdominal pain, and hepatomegaly, including distinct liver abscesses.1 According to recent estimates, the global seroprevalence of Toxocara infection among healthy persons is approximately 19%. However, it is exceptionally high in Vietnam at 45.7%.2,3 This report describes a Vietnamese patient with hepatic VLM induced by T. canis infection, presenting with symptoms mimicking a pyogenic liver abscess. We underscore the diagnostic challenges and the importance of a comprehensive approach.

A 21-year-old male undergraduate student presented to our emergency department with a 7-day history of constant fever with chills and dull pain in the right upper quadrant, unaffected by position or meals. He denied nausea, vomiting, breathlessness, coughing, chest pain, or changes in urinary and bowel function. His medical history was unremarkable, and he denied consuming uncooked meat or vegetables or traveling to exotic locations within the past year. However, he reported owning a pet dog.

On examination, the patient was oriented and alert, with normal vital signs except for a temperature of 39°C. Abdominal examination revealed right upper quadrant tenderness without guarding or rebound tenderness. Laboratory investigations showed leukocytosis (17.28 G/L) with neutrophilia (13.89 G/L), lymphocytes (1.38 G/L), and eosinophils (0.58 G/L). CRP was elevated (193.1 mg/L), while liver and renal function tests were normal. Abdominal ultrasound revealed multiple echogenic foci with sharp margins within both liver lobes, and a subsequent CT scan showed multiple ill-defined hypodense oval lesions with rim enhancement, some clustered together (Fig. 1), initially interpreted as pyogenic abscesses.

Despite treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics (ceftriaxone and metronidazole, followed by meropenem and vancomycin), the patient's fever persisted, prompting further investigation. Blood and stool cultures were negative. Serological tests for antibodies against various parasitic infections (Echinococcosis, Fasciola hepatica, Entamoeba histolytica, and Toxocara canis) were conducted, and the results were positive specifically for Toxocara canis antibodies, with elevated IgE levels (1,760 IU/L) and normal AFP. A liver biopsy revealed inflammatory parenchyma with neutrophil, eosinophil, lymphocyte infiltration, and Charcot-Leyden crystals, suggesting a parasitic infection. No parasites or ovals were identified in the smears (Fig. 2).

Based on the serological and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of hepatic VLM caused by Toxocara canis was made. Albendazole 400 mg b.i.d. was added to the treatment regimen for 5 days. Two days post-treatment, the fever resolved, and eosinophil levels increased to 950 cells/mm3 (12.5%), while IgE levels decreased to 530 IU/L. Follow-up at 15 and 30 days showed significant clinical improvement and resolution of the lesions on ultrasonography. One year after discharge, the patient remained asymptomatic, with normal liver parenchyma on abdominal ultrasound.

Vietnam, situated in Southeast Asia, harbors a tropical climate conducive to the transmission of Toxocara and various other helminths.4,5 Toxocariasis is a parasitic zoonosis stemming from the eggs or larvae of Toxocara canis or, less commonly, Toxocara cati, typically found in dogs and cats. The eggs are excreted in the feces of the primary host. Humans can become accidental hosts by ingesting raw paratenic meat, or egg-contaminated soil.1

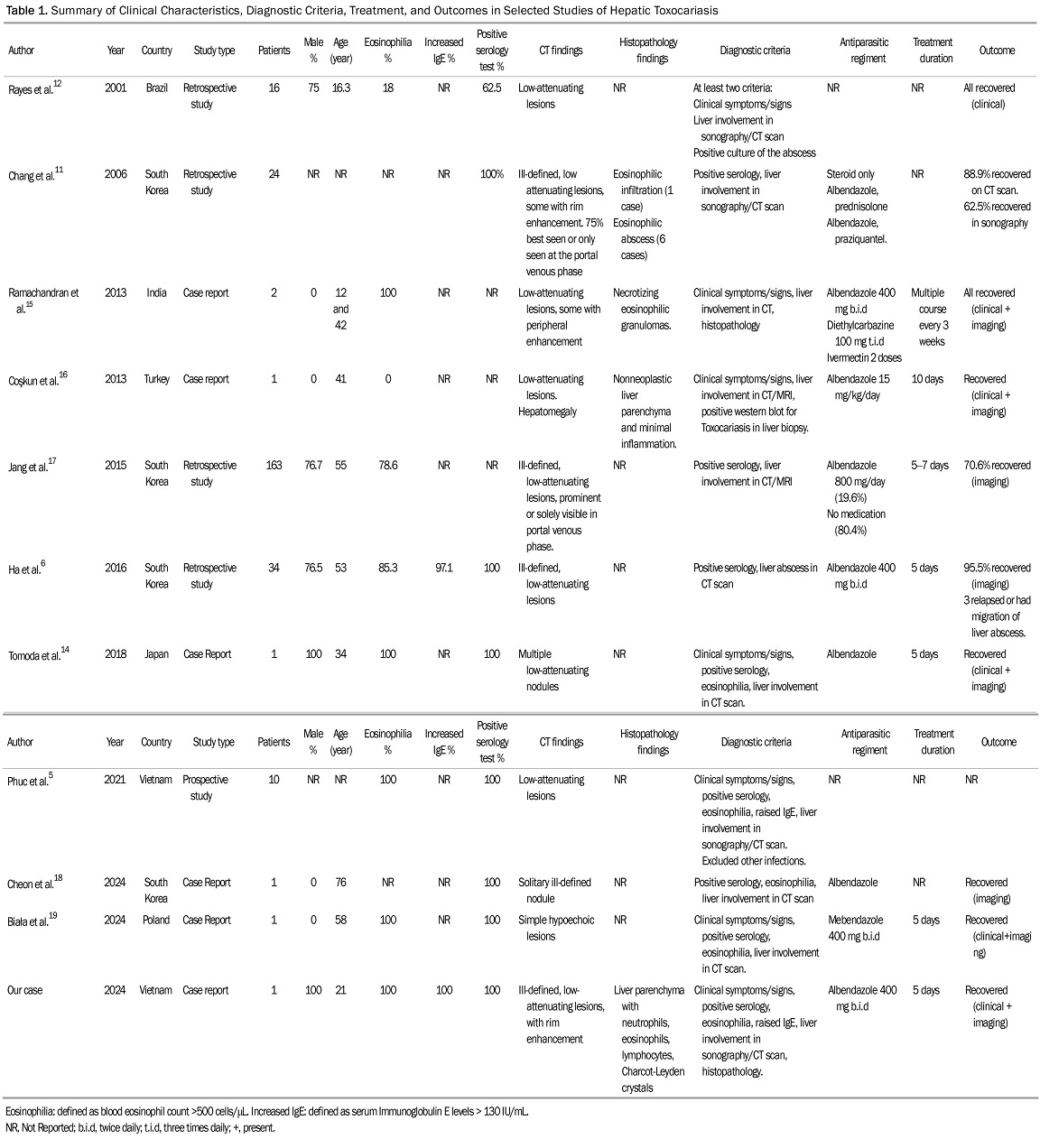

We identified 10 studies on hepatic toxocariasis using the MEDLINE database, including case reports, retrospective, and prospective studies. These studies showed that VLM induced by Toxocara can affect individuals of all age groups, with males being more susceptible than females (Table 1). The clinical course of liver Toxocariasis varies, ranging from asymptomatic infection in approximately 50% of patients to incidental eosinophilia and hepatic abscesses with symptoms such as fever, chills, and right upper quadrant pain. These manifestations are non-specific and can sometimes be confused with other liver diseases. This ambiguity poses a significant challenge in diagnosis based solely on clinical presentation.

Regarding laboratory indices of liver toxocariasis, the increase in the blood eosinophil count and the concentration of serum total IgE are the most prominent.6 Leukocytosis and extremely high eosinophilia are present in over 30% of cases of VLM.1,7 Higher IgE concentrations and eosinophil counts have been documented to be associated with hepatic involvement but not in other organs.5 Notably, our case exhibited neutrophilia that closely resembled a pyogenic origin, with only a slight presence of eosinophilia. A definite diagnosis of human toxocariasis involves detecting larvae or larval DNA in tissue or body fluids samples. However, obtaining tissue biopsies or fluid samples for diagnosis is not always feasible. ELISA based on Toxocara antigens from infective-stage larvae is a widely preferred method for diagnosis due to its non-invasive nature. The Toxocara-ELISA test shows high sensitivity (78%) and specificity (92%).7,8 However, IgG antibodies from toxocariasis may persist for up to 5 years in patients recovering from the infection and can cross-react with other helminthic diseases. In Vietnam, testing of healthy individuals' blood samples for toxocariasis IgG revealed extremely high levels of antibodies.2,9 Additionally, up to 58.7% of household residents with dogs and cats as pets have been found to have Toxocara antibodies.4 The high prevalence of serum Toxocara antibodies renders serological tests less definitive for confirming active disease.2 Therefore, to diagnose active toxocariasis, a seropositive result should also be accompanied by a clinical course aligned with active disease (including compatible symptoms, eosinophilia, high IgE levels, and histopathological samples). In this context, liver biopsy becomes crucial for confirming active infection.

Liver involvement in toxocariasis can be detected through ultrasonography, CT scan, or MRI. The lesions present as multiple, ill-defined, oval, or elongated, low-attenuating nodules in images acquired during the portal venous phase of dynamic CT scans reflecting the distribution of T. canis larvae through the portal blood flow.10 These characteristics are consistent across studies of hepatic toxocariasis (Table 1). Unlike liver metastases, which are often spherical with variable sizes and arterial rim enhancement, toxocariasis nodules lack these features. Histopathologically, these nodules are associated with pathological changes, including periportal eosinophilic infiltration, abscess formation, granuloma development with central necrosis, and peripheral edema.10-12

Toxocariasis can lead to the formation of secondary pyogenic abscesses. Distinguishing primary parasitic lesions from bacterial ones presents clinical challenges. Initially, our case exhibited CT scan results resembling clustered abscesses, raising suspicion of pyogenic abscess due to fever, neutrophilia, and inconclusive histology.10,12 However, our diagnosis ultimately indicated hepatic VLM toxocariasis, supported by clinical evidence: mild eosinophilia, elevated IgE levels, the detection of serum IgG antibody to Toxocara antigen, and unresponsiveness to antibiotics. The presence of characteristic eosinophilic infiltration, along with Charcot-Leyden crystals in the biopsy sample, further affirmed the parasitic etiology.1,11 Treatment varies between studies, with the preferred anthelminthic regimen being Albendazole 400mg administered twice daily (b.i.d.) for 5–7 days (Table 1).1,13-19 Albendazole is preferred for treating VLM due to its superior systemic absorption, tissue penetration, and broad-spectrum activity, with a 78.0% efficacy rate. Side effects occurred in 15.0% of cases, primarily liver dysfunction, but were mild to moderate with no severe cases reported.13 Some cases use steroids or combination therapies to manage severe or refractory cases.11 In our case, the patient exhibited a solid response to the albendazole treatment regimen and duration within two weeks. Monitoring the success of treatment involves assessing improvements in clinical presentation and radiologic findings, as well as a reduction in eosinophil count. In toxocariasis cases, eosinophilia mirrors the immune response to migrating Toxocara larvae. We hypothesize that post-treatment, eosinophilia may intensify due to the immune system's reaction to larval demise and parasite clearance.

In conclusion, our case report highlights the atypical clinical presentation of underestimated VLM due to toxocariasis, particularly its potential to mimic pyogenic abscesses in the absence of initial extreme eosinophilia. Given the limitations of serological testing in endemic areas, a comprehensive diagnostic approach combining serological testing, histopathological analysis, and clinical correlation is crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management of hepatic toxocariasis. Increased awareness among healthcare professionals about the varied presentations of this parasitic infection and a high index of suspicion in endemic regions is essential to ensure timely diagnosis and treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Ma G, Holland CV, Wang T, et al. 2018; Human toxocariasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 18:e14–e24. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30331-6. PMID: 28781085.

2. Rostami A, Riahi SM, Holland CV, et al. 2019; Seroprevalence estimates for toxocariasis in people worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 13:e0007809. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007809. PMID: 31856156. PMCID: PMC6922318.

3. Elefant GR, Shimizu SH, Sanchez MC, Jacob CM, Ferreira AW. 2006; A serological follow-up of toxocariasis patients after chemotherapy based on the detection of IgG, IgA, and IgE antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Lab Anal. 20:164–172. DOI: 10.1002/jcla.20126. PMID: 16874812. PMCID: PMC6807646.

4. Anh NT, Thuy DT, Hoan DH, Hop NT, Dung DT. 2016; Levels of Toxocara infections in dogs and cats from urban Vietnam together with associated risk factors for transmission. J Helminthol. 90:508–510. DOI: 10.1017/S0022149X15000619. PMID: 26223509.

5. Phuc LDV, Loi CB, Quang HH, et al. 2021; Clinical and laboratory findings among patients with toxocariasis in medic medical center, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam in 2017-2019. Iran J Parasitol. 16:538–547.

6. Ha KH, Song JE, Kim BS, Lee CH. 2016; Clinical characteristics and progression of liver abscess caused by toxocara. World J Hepatol. 8:757–761. DOI: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i18.757. PMID: 27366302. PMCID: PMC4921797.

7. Rubinsky-Elefant G, Hirata CE, Yamamoto JH, Ferreira MU. 2010; Human toxocariasis: diagnosis, worldwide seroprevalences and clinical expression of the systemic and ocular forms. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 104:3–23. DOI: 10.1179/136485910X12607012373957. PMID: 20149289.

8. Hotez PJ, Wilkins PP. 2009; Toxocariasis: America's most common neglected infection of poverty and a helminthiasis of global importance? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 3:e400. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000400. PMID: 19333373. PMCID: PMC2658740.

9. Nguyen T, Cheong FW, Liew JW, Lau YL. 2016; Seroprevalence of fascioliasis, toxocariasis, strongyloidiasis and cysticercosis in blood samples diagnosed in Medic Medical Center Laboratory, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam in 2012. Parasit Vectors. 9:486. DOI: 10.1186/s13071-016-1780-2. PMID: 27595647. PMCID: PMC5011968.

10. Lambertucci JR, Rayes AA, Serufo JC, Nobre V. 2001; Pyogenic abscesses and parasitic diseases. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 43:67–74. DOI: 10.1590/S0036-46652001000200003. PMID: 11340478.

11. Chang S, Lim JH, Choi D, et al. 2006; Hepatic visceral larva migrans of Toxocara canis: CT and sonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 187:W622–W629. DOI: 10.2214/AJR.05.1416. PMID: 17114516.

12. Rayes AA, Teixeira D, Serufo JC, Nobre V, Antunes CM, Lambertucci JR. 2001; Human toxocariasis and pyogenic liver abscess: a possible association. Am J Gastroenterol. 96:563–566. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03471.x. PMID: 11232707.

13. Hombu A, Yoshida A, Kikuchi T, Nagayasu E, Kuroki M, Maruyama H. 2019; Treatment of larva migrans syndrome with long-term administration of albendazole. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 52:100–105. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.07.002. PMID: 28754237.

14. Tomoda Y, Futami S, Sumida K, Tanaka K. 2018; Neglected parasitic infection: toxocariasis. BMJ Case Rep. 2018:bcr2018224492. DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2018-224492. PMID: 29540354. PMCID: PMC5878241.

15. Ramachandran J, Chandramohan A, Gangadharan SK, Unnikrishnan LS, Priyambada L, Simon A. 2013; Visceral larva migrans presenting as multiple liver abscesses. Trop Doct. 43:154–157. DOI: 10.1177/0049475513507254. PMID: 24100348.

16. Coşkun F, Akıncı E. 2013; Hepatic toxocariasis: a rare cause of right upper abdominal pain in the emergency department. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 37:151–153. DOI: 10.5152/tpd.2013.33. PMID: 23955916.

17. Jang EY, Choi MS, Gwak GY, et al. 2015; Enhanced resolution of eosinophilic liver abscess associated with toxocariasis by albendazole treatment. Korean J Gastroenterol. 65:222–228. DOI: 10.4166/kjg.2015.65.4.222. PMID: 25896156.

18. Cheon M, Yoo J. 2023; Pulmonary and liver toxocariasis mimicking metastatic tumors in a patient with colon cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 14:58. DOI: 10.3390/diagnostics14010058. PMID: 38201367. PMCID: PMC10795704.

19. Biała M, Nieleńczuk J, Chodorowska A, Szetela B. 2024; Challenges in toxocariasis diagnosis: From pericarditis, through hepatic tumor, to the detection of brain aneurysms: Case report. Pathogens. 13:254. DOI: 10.3390/pathogens13030254. PMID: 38535597. PMCID: PMC10975517.

Fig. 1

CT Imaging of liver abscesses. CT scan acquired during the portal venous phase highlights (A) axial and (B) sagittal views. The images depict numerous ill-defined hypoattenuating lesions (indicated by arrows) with surrounding rim enhancement, forming clusters within both liver lobes. These findings are indicative of liver abscesses.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download