Abstract

Background: The concurrent detection of human cytomegalovirus (CMV) with UL97 and UL54 mutations is crucial for prescribing adequate antiviral treatment when drug-resistant CMV infection is suspected. We investigated the frequency of resistance-conferring mutations among patients with persistent or recurrent CMV infection and further reviewed the subgroup with UL54 mutations without UL97 mutations. Methods: Patients with persistent or recurrent CMV infection after 4 weeks of treatment with ganciclovir or foscarnet were consecutively enrolled between November 2012 and May 2019. The direct sequencing of UL97 and UL54 was performed to detect resistance mutations in CMV. Results: A total of 101 sequencing datasets were obtained from 65 enrolled patients. CMV UL97 and UL54 mutations were detected in 15.4% (10/65) and 9% (6/65) of patients, respectively. The CMV retrieved from two patients (3%) had mutations in both genes. Four patients with CMV UL54 mutations alone had a history of haploidentical peripheral blood stem cell transplantation, and foscarnet was administered for over 4 weeks to these patients; 21.5% of patients had suspected resistant CMV infection with either UL97 or UL54 mutations. Conclusion: In this study, CMV UL54 mutations but not UL97 mutations were found in patients subjected to prolonged foscarnet administration for CMV disease.

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease is commonly treated with ganciclovir (GCV) or its oral prodrug, valganciclovir. Second-line treatment drugs for CMV disease, including foscarnet (FOS) and cidofovir (CDV), target UL54 DNA polymerase. Prolonged antiviral therapy can lead to mutations in the UL97 and/ or UL54 genes [1]. CMV resistance to these drugs is uncommon, ranging from 0.4% to 11.9% in solid organ transplant patients and 1% to 5% in patients who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplant [2,3]. However, drug-resistant CMV infection is associated with inferior prognosis in these two patient groups [2,4].

UL97 mutations are well-known as the most prevalent causes for CMV resistance [5,6]. A previous study [6] showed that approximately 30% of 570 samples submitted to a commercial laboratory in the US were positive for UL97 or UL54 gene mutations, and 62.5% of 64 samples with UL54 mutations also possessed UL97 mutations. Therefore, UL97 mutations are primarily tested in patients suspected to be infected with resistant strains of CMV, and UL54 mutations are tested concurrently or only in UL97 mutation-negative cases. UL54 mutations, which usually appear after UL97 mutations, are associated with resistance to not only the first-line drug GCV, but also to the other second-line agents such as CDV and FOS [7]. Therefore, UL54 as well as UL97 mutations should be investigated in CMV patients suspected with antiviral resistance. Here, we describe the frequency of CMV resistance-related gene mutations among patients with persistent or recurrent CMV infection, and further reviewed the subgroup possessing UL54 mutations without UL97 mutations.

Patients suspected to be infected with resistant CMV strains following persistent or recurrent CMV detection after 4 weeks of antiviral therapy using GCV or FOS were subjected to UL97 and UL54 mutation testing in a consultation-based setting between November 2012 and May 2019 at the Asan Medical Center. Clinical and laboratory data were obtained from the hospital’s electric medical records and laboratory information system. CMV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with Artus CMV PCR Test (QIAGEN Gaithersburg, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) using a Rotor-Gene Q (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany), and the threshold of CMV detection was set as 2.42 log copies/mL. In September 2018, Artus CMV PCR Test was replaced with Abbott RealTime CMV Assay (Abbott Molecular Inc., Des Plaines, IL, USA) with the limit of detection value set at 1.49 log IU/mL. Direct sequencing of UL97 and UL54 genes was performed for detecting the CMV resistance mutations as described previously [8,9]. Variants were detected by comparing with the reference strain AD169 (GenBank accession number BK000394). Detected variants were analyzed along with the previously reported ones and synonymous variants were not analyzed [10,11]. Categorical data were analyzed with chi-square test using MedCalc (version 20.011; MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

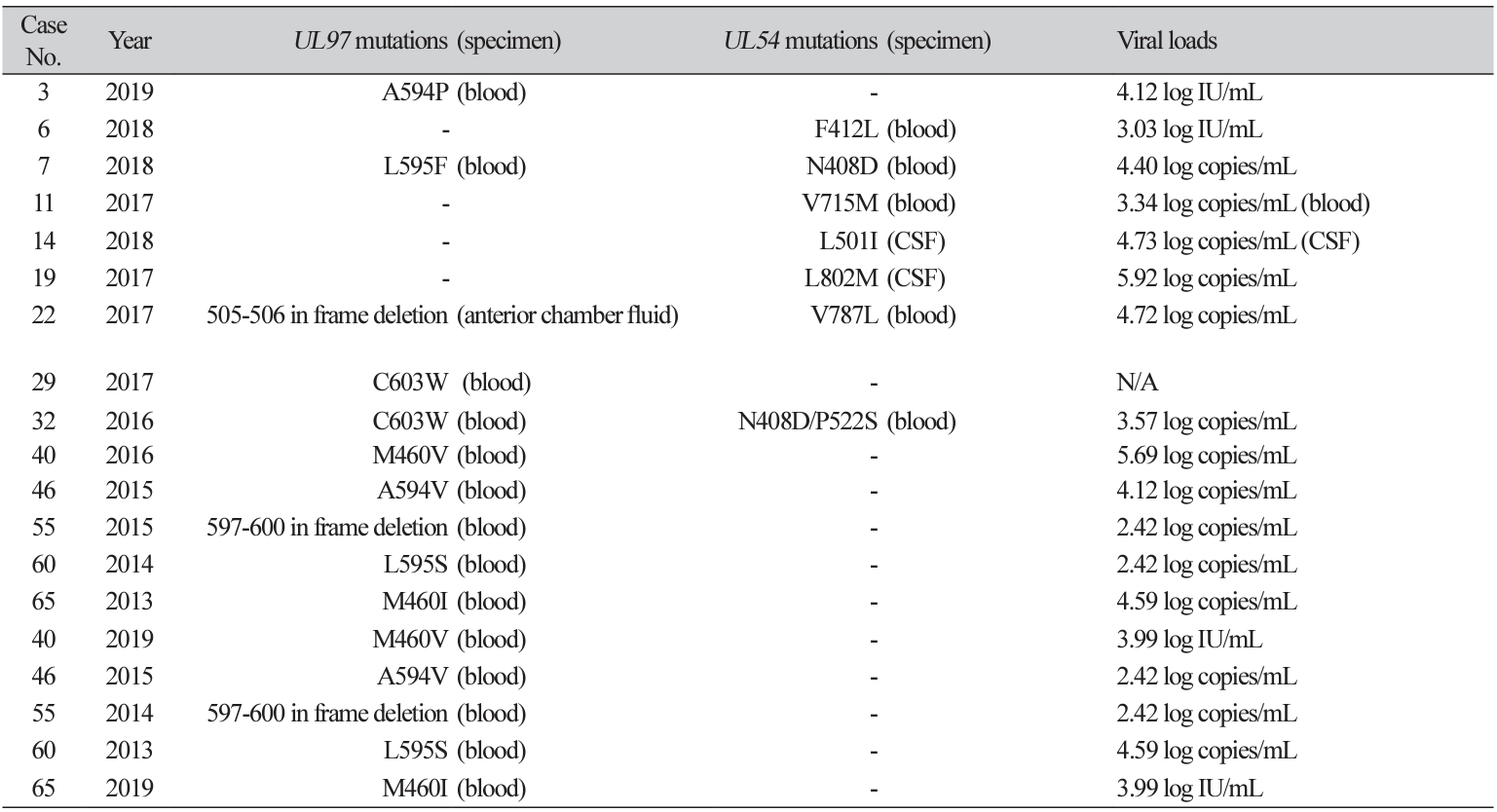

A total of 101 CMV DNA samples from 65 patients were subjected to CMV resistance testing. The median age of study patients was 19 years and 62% of them were male. 75% of study patients had underlying disease of hematologic malignancy. All mutations in UL97 or UL54 genes were identified in 14 patients (21.5%). 10 (15.4%) and 6 (9.2%) patients exhibited mutations in the UL97 and UL54 genes, respectively. Observed mutations from both genes are presented in Table 1. Between patients with and without any mutation in UL97 and UL54 genes, there was no significant difference of underlying disease of hematologic malignancy (P=0.31) and sex (P=0.32). Changes in the test numbers of samples and % sample harboring any mutation were not significant during the study period; the test numbers of samples (% sample harboring any mutation) were 5 (0%) in 2012, 4 (25.0%) in 2013, 12 (8.3%) in 2014, 18 (16.7%) in 2015, 15 (13.3%) in 2016, 17 (23.5%) in 2017, 26 (26.9%) in 2018, and 4 (25.0%) in 2019.

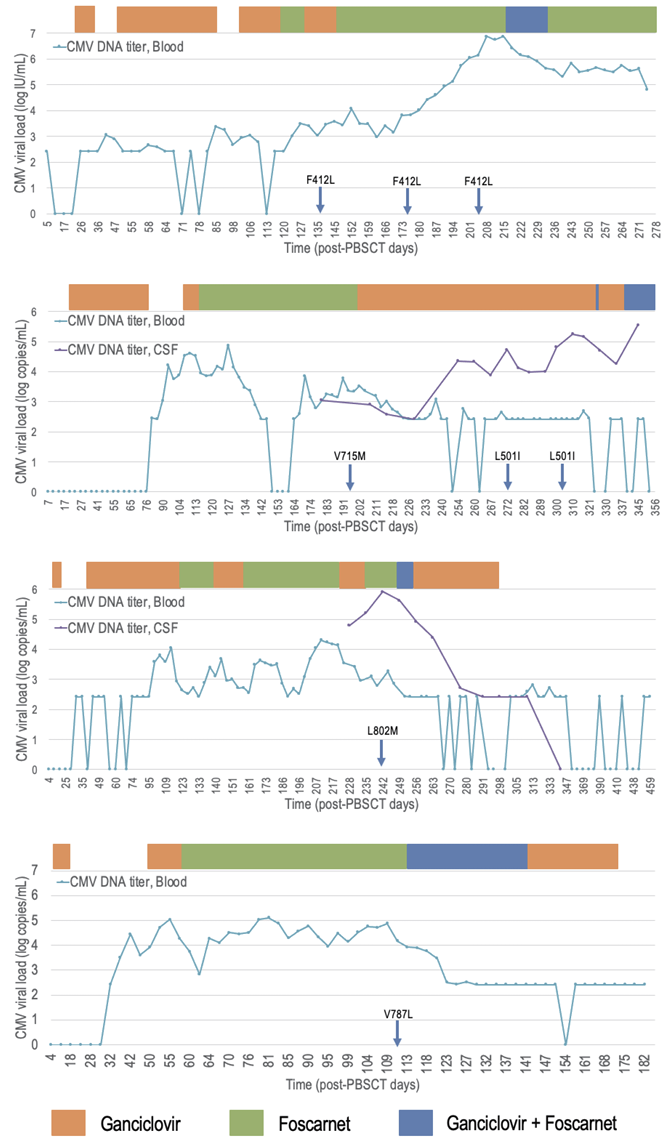

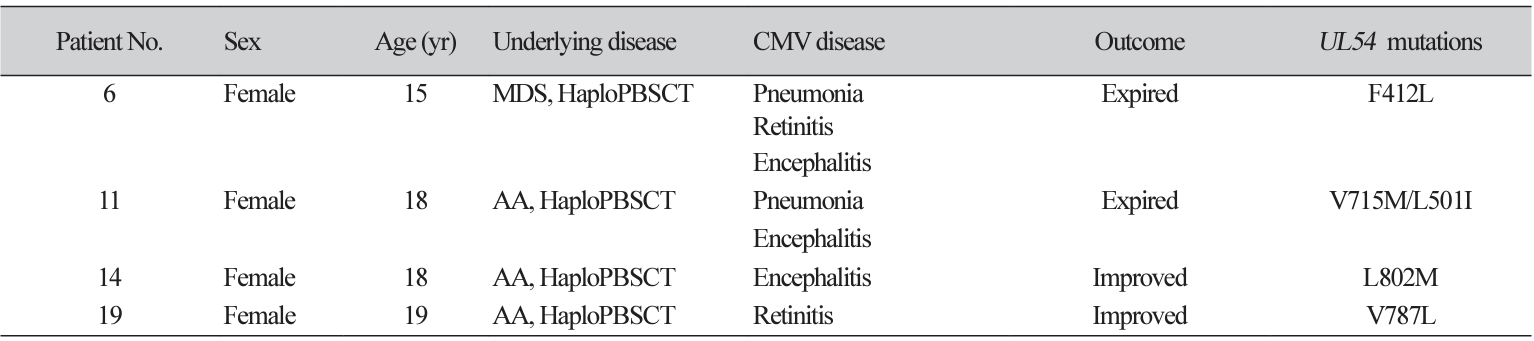

Four cases had UL54 mutations alone. Patient characteristics and CMV kinetics of these cases are described in Table 2 and Fig. 1, respectively. They all had a history of haploidentical peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (HaploPBSCT) and FOS was administered to these four patients before the detection of variants.

Approximately, one-fifth of the patients with persistent or recurrent CMV exhibited at least one mutation in UL97 and UL54. High prevalence of CMV mutations was mainly due to the inclusion criteria of patients with persistent or recurrent CMV after 4 weeks of antiviral treatment using GCV or FOS. Resistance emergence varied along with organ type among solid organ transplantation (SOT) patients [3]; thus, the composition of the included SOT patients could affect the mutation prevalence in this study.

All except two mutations were well-known mutations [12-14]. The two unknown mutations are both inframe deletions. In-frame deletion of codon 597-600 is within the hot-spots for GCV resistance (codons 460, 520, and 590-607) [12]. In-frame deletion of the UL97 gene, especially at codons 591 to 603 is less-common but has been reported continuously, and some reported these mutations to confer 4- to 10-fold resistance [13]. The other one was an in-frame deletion of codons 505-506 located on the kinase domain, which is not a wellknown mutation or polymorphism [14], but a variant of unknown significance.

All cases with UL54 mutations alone were related to HaploPBSCT and exhibited a prolonged treatment history with FOS. A previous study reported three patients with UL54 mutations alone, who were hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients, and all were treated with both GCV and FOS [15]. In line with this, prolonged use of FOS is possibly related to CMV resistance conferred by UL54 mutations without UL97 mutations. This finding highlights the importance of testing UL54 mutations especially in patients treated with FOS.

Our study has several limitations due to its observational nature. Furthermore, our study population was limited to patients who were clinically suspected to have resistant CMV infection, and therefore, some patients subjected to more than 4 weeks of antiviral therapy for CMV treatment were probably excluded. Additionally, the number of patients infected with drug-resistant CMV in one institution was relatively small.

Conclusively, 21.5% of patients suspected with resistant CMV infection possessed one of the two UL97 and UL54 mutations. In addition, UL54 mutations without UL97 mutations was found in patients subjected to prolonged administration of FOS for CMV disease.

Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Asan Medical Center (No. 2012-0401) approved this study.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant No. HI18C2383).

REFERENCES

1. Scott GM, Isaacs MA, Zeng F, Kesson AM, Rawlinson WD. Cytomegalovirus antiviral resistance associated with treatment induced UL97 (protein kinase) and UL54 (DNA polymerase) mutations. J Med Virol 2004;74:85-93.

.

2. Liu J, Kong J, Chang YJ, Chen H, Chen YH, Han W, et al. Patients with refractory cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection following allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation are at high risk for CMV disease and non-relapse mortality. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21:1121.e9-15.

.

3. Fisher CE, Knudsen JL, Lease ED, Jerome KR, Rakita RM, Boeckh M, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:57-63.

.

4. Avery RK, Arav-Boger R, Marr KA, Kraus E, Shoham S, Lees L, et al. Outcomes in transplant recipients treated with foscarnet for ganciclovir-resistant or refractory cytomegalovirus infection. Transplantation 2016;100:e74-80.

.

5. Myhre HA, Haug Dorenberg D, Kristiansen KI, Rollag H, Leivestad T, Asberg A, et al. Incidence and outcomes of ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus infections in 1244 kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation 2011;92:217-23.

.

6. Kleiboeker S, Nutt J, Schindel B, Dannehl J, Hester J. Cytomegalovirus antiviral resistance: characterization of results from clinical specimens. Transpl Infect Dis 2014;16:561-7.

.

7. Gilbert C, Azzi A, Goyette N, Lin SX, Boivin G. Recombinant phenotyping of cytomegalovirus UL54 mutations that emerged during cell passages in the presence of either ganciclovir or foscarnet. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011;55:4019-27.

.

8. Sung H, An D, Lee SO, Choi SH, Kim SH, Chi HS, et al. Detection of a UL97 gene mutation conferring ganciclovir resistance in human cytomegalovirus: prevalence of the D605E polymorphism in Korean immunocompromised patients. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2012;42:429-34.

.

9. Allice T, Busca A, Locatelli F, Falda M, Pittaluga F, Ghisetti V. Valganciclovir as pre-emptive therapy for cytomegalovirus infection post-allogenic stem cell transplantation: implications for the emergence of drug-resistant cytomegalovirus. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;63:600-8.

.

10. Razonable RR. Drug-resistant cytomegalovirus: clinical implications of specific mutations. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2018;23:388-94.

.

11. Chou S. Advances in the genotypic diagnosis of cytomegalovirus antiviral drug resistance. Antiviral Res 2020;176:104711.

.

12. Lurain NS, Chou S. Antiviral drug resistance of human cytomegalovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010;23:689-712.

.

13. Chou S, Ercolani RJ, Vanarsdall AL. Differentiated levels of ganciclovir resistance conferred by mutations at codons 591 to 603 of the cytomegalovirus UL97 kinase gene. J Clin Microbiol 2017;55:2098-104.

.

14. Tamura S, Osawa S, Ishida N, Miyazu T, Tani S, Yamade M, et al. Prevalence of UL97 gene mutations and polymorphisms in cytomegalovirus infection in the colon associated with or without ulcerative colitis. Sci Rep 2021;11:13676.

.

15. Kim SJ, Huang YT, Foldi J, Lee YJ, Maloy M, Giralt SA, et al. Cytomegalovirus resistance in CD34+-selected hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis 2018;20:e12881.

.

Fig. 1.

CMV kinetics of four cases with UL54 mutations alone (Patients #6, #11, #14, #19). Bar graph indicates the duration of antiviral drug administration. Blue arrows indicate the specimen dates of CMV viruses with specified UL54 mutations. CMV, cytomegalovirus; PBSCT, peripheral blood stem cell transplantation; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download