1. Choo JM, Baek SJ, Kwak JM, Kim J, Kim SH. Clinical characteristics and oncologic outcomes in patients with preoperative clinical T3 and T4 colon cancer who were staged as pathologic T3. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2020; 99:37–43. PMID:

32676480.

2. Paik JH, Ryu CG, Hwang DY. Risk factors of recurrence in TNM stage I colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2023; 104:281–287. PMID:

37179701.

3. Cho JR, Lee KW, Oh HK, Kim JW, Kim JW, Kim DW, et al. Effectiveness of oral fluoropyrimidine monotherapy as adjuvant chemotherapy for high-risk stage II colon cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2022; 102:271–280. PMID:

35611086.

4. Kang MY, Paik JH, Ryu CG, Hwang DY. Adjuvant oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy effect after treatment of colorectal hepatic metastasis. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2021; 101:160–166. PMID:

34549039.

5. Shin R, Lee S, Han KS, Sohn DK, Moon SH, Choi DH, et al. Guidelines for accreditation of endoscopy units: quality measures from the Korean Society of Coloproctology. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2021; 100:154–165. PMID:

33748029.

6. Yang IJ, Oh HK, Lee J, Suh JW, Ahn HM, Shin HR, et al. Efficacy of geriatric multidisciplinary oncology clinic in the surgical treatment decision-making process for frail elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2022; 103:169–175. PMID:

36128034.

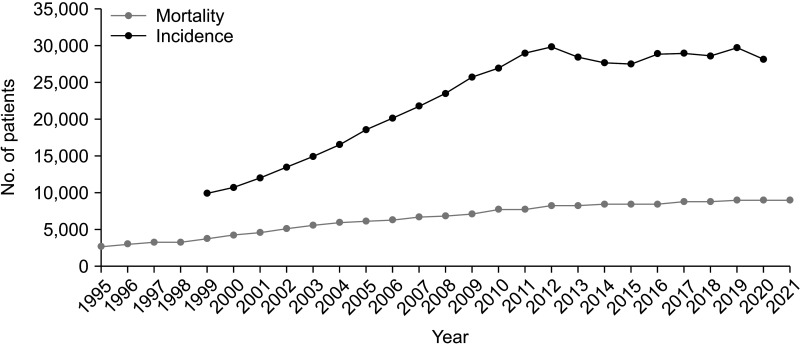

8. Kim MH, Park S, Yi N, Kang B, Park IJ. Colorectal cancer mortality trends in the era of cancer survivorship in Korea: 2000-2020. Ann Coloproctol. 2022; 38:343–352. PMID:

36353833.

10. Chang MC, Choo YJ, Kim S. Effect of prehabilitation on patients with frailty undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2023; 104:313–324. PMID:

37337603.

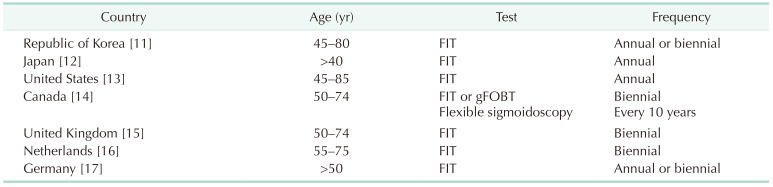

11. Sohn DK, Kim MJ, Park Y, Suh M, Shin A, Lee HY, et al. The Korean guideline for colorectal cancer screening. J Korean Med Assoc. 2015; 58:420–432.

12. Saito Y, Oka S, Kawamura T, Shimoda R, Sekiguchi M, Tamai N, et al. Colonoscopy screening and surveillance guidelines. Dig Endosc. 2021; 33:486–519. PMID:

33713493.

13. Shaukat A, Kahi CJ, Burke CA, Rabeneck L, Sauer BG, Rex DK. ACG clinical guidelines: colorectal cancer screening 2021. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021; 116:458–479. PMID:

33657038.

14. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for colorectal cancer in primary care. CMAJ. 2016; 188:340–348. PMID:

26903355.

17. Brinkmann M, Diedrich L, Krauth C, Robra BP, Stahmeyer JT, Dreier M. General populations’ preferences for colorectal cancer screening: rationale and protocol for the discrete choice experiment in the SIGMO study. BMJ Open. 2021; 11:e042399.

18. Park B, Her EY, Lee K, Nari F, Jun JK, Choi KS, et al. Overview of the National Cancer Screening Program for Colorectal Cancer in Korea over 14 Years (2004-2017). Cancer Res Treat. 2023; 55:910–917. PMID:

36915246.

19. Li JN, Yuan SY. Fecal occult blood test in colorectal cancer screening. J Dig Dis. 2019; 20:62–64. PMID:

30714325.

20. Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Irwig L, Towler B, Watson E. Screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test, Hemoccult. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; 2007:CD001216. PMID:

17253456.

21. Hu LF, Yue QQ, Tang T, Sun YX, Zou JY, Huang YT, et al. Knowledge and belief of fecal occult blood screening: a systematic review. Public Health Nurs. 2023; 40:782–789. PMID:

37177843.

22. Meklin J, Syrjänen K, Eskelinen M. Colorectal cancer screening with traditional and new-generation fecal immunochemical tests: a critical review of fecal occult blood tests. Anticancer Res. 2020; 40:575–581. PMID:

32014898.

23. Tinmouth J, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Allison JE. Faecal immunochemical tests versus guaiac faecal occult blood tests: what clinicians and colorectal cancer screening programme organisers need to know. Gut. 2015; 64:1327–1337. PMID:

26041750.

24. Shaukat A, Levin TR. Current and future colorectal cancer screening strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022; 19:521–531. PMID:

35505243.

25. Williams JR, Ayscue JM. Colorectal cancer screening: a review of current screening options, timing, and guidelines. J Surg Oncol. 2023; 127:1236–1246. PMID:

37222695.

26. Doubeni CA, Levin TR. In screening for colorectal cancer, is the FIT right for the right side of the colon? Ann Intern Med. 2018; 169:650–651. PMID:

30285038.

27. Santiago L, Toro DH. Effectiveness of multiple consecutive fecal immunohistochemical testing for colorectal cancer screening. P R Health Sci J. 2022; 41:117–122. PMID:

36018738.

28. Jayasinghe M, Prathiraja O, Caldera D, Jena R, Coffie-Pierre JA, Silva MS, et al. Colon cancer screening methods: 2023 update. Cureus. 2023; 15:e37509. PMID:

37193451.

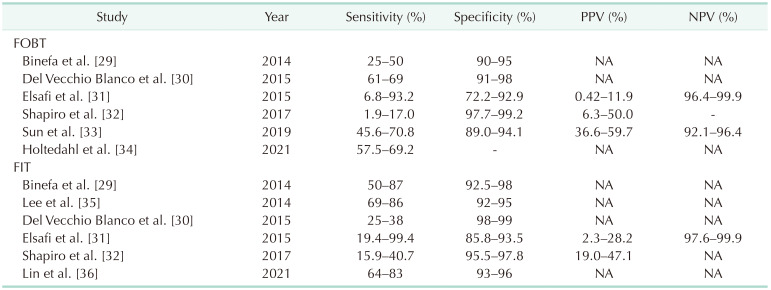

29. Binefa G, Rodríguez-Moranta F, Teule A, Medina-Hayas M. Colorectal cancer: from prevention to personalized medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:6786–6808. PMID:

24944469.

30. Del Vecchio Blanco G, Paoluzi OA, Sileri P, Rossi P, Sica G, Pallone F. Familial colorectal cancer screening: when and what to do? World J Gastroenterol. 2015; 21:7944–7953. PMID:

26185367.

31. Elsafi SH, Alqahtani NI, Zakary NY, Al Zahrani EM. The sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and likelihood ratios of fecal occult blood test for the detection of colorectal cancer in hospital settings. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015; 8:279–284. PMID:

26392783.

32. Shapiro JA, Bobo JK, Church TR, Rex DK, Chovnick G, Thompson TD, et al. A comparison of fecal immunochemical and high-sensitivity guaiac tests for colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017; 112:1728–1735. PMID:

29016558.

33. Sun J, Fei F, Zhang M, Li Y, Zhang X, Zhu S, et al. The role of mSEPT9 in screening, diagnosis, and recurrence monitoring of colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019; 19:450. PMID:

31088406.

34. Holtedahl K, Borgquist L, Donker GA, Buntinx F, Weller D, Campbell C, et al. Symptoms and signs of colorectal cancer, with differences between proximal and distal colon cancer: a prospective cohort study of diagnostic accuracy in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2021; 22:148. PMID:

34238248.

35. Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, Levin TR, Corley DA. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 160:171. PMID:

24658694.

36. Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021; 325:1978–1998. PMID:

34003220.

37. Shin A, Choi KS, Jun JK, Noh DK, Suh M, Jung KW, et al. Validity of fecal occult blood test in the national cancer screening program, Korea. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e79292. PMID:

24260189.

38. Selby K, Jensen CD, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, Schottinger JE, Zhao WK, et al. Influence of varying quantitative fecal immunochemical test positivity thresholds on colorectal cancer detection: a community-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 169:439–447. PMID:

30242328.

39. Bailey SE, Abel GA, Atkins A, Byford R, Davies SJ, Mays J, et al. Diagnostic performance of a faecal immunochemical test for patients with low-risk symptoms of colorectal cancer in primary care: an evaluation in the South West of England. Br J Cancer. 2021; 124:1231–1236. PMID:

33462361.

40. Morikawa T, Kato J, Yamaji Y, Wada R, Mitsushima T, Shiratori Y. A comparison of the immunochemical fecal occult blood test and total colonoscopy in the asymptomatic population. Gastroenterology. 2005; 129:422–428. PMID:

16083699.

41. Khan AA, Klimovskij M, Harshen R. Accuracy of faecal immunochemical testing in patients with symptomatic colorectal cancer. BJS Open. 2020; 4:1180–1188. PMID:

32949085.

42. Terhaar sive Droste JS, van Turenhout ST, Oort FA, van der Hulst RW, Steeman VA, Coblijn U, et al. Faecal immunochemical test accuracy in patients referred for surveillance colonoscopy: a multicentre cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012; 12:94. PMID:

22828158.

43. Uppara M, Adaba F, Askari A, Clark S, Hanna G, Athanasiou T, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of pyruvate kinase M2 isoenzymatic assay in diagnosing colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2015; 13:48. PMID:

25888768.

44. Plantener E, Deding U, Madsen JB, Kroijer R, Madsen JS, Baatrup G. Using fecal immunochemical test values below conventional cut-off to individualize colorectal cancer screening. Endosc Int Open. 2022; 10:E413–E419. PMID:

35528219.

45. Law J, Rajan A, Trieu H, Azizian J, Berry R, Beaven SW, et al. Predictive modeling of colonoscopic findings in a fecal immunochemical test-based colorectal cancer screening program. Dig Dis Sci. 2022; 67:2842–2848. PMID:

34350518.

46. Niedermaier T, Tikk K, Gies A, Bieck S, Brenner H. Sensitivity of fecal immunochemical test for colorectal cancer detection differs according to stage and location. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; 18:2920–2928. PMID:

31988043.

47. Heer E, Ruan Y, Pader J, Mah B, Ricci C, Nguyen T, et al. Performance of the fecal immunochemical test for colorectal cancer and advanced neoplasia in individuals under age 50. Prev Med Rep. 2023; 32:102124. PMID:

36875511.

48. Park SS, Park SC, Lee DE, Lee DW, Yu K, Park HC, et al. The risk of surgical site infection of oral sulfate tablet versus sodium picosulfate for bowel preparation in colorectal cancer surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2022; 103:96–103. PMID:

36017141.

49. Dominitz JA, Robertson DJ. Understanding the results of a randomized trial of screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2022; 387:1609–1611. PMID:

36214591.

50. Bretthauer M, Løberg M, Wieszczy P, Kalager M, Emilsson L, Garborg K, et al. Effect of colonoscopy screening on risks of colorectal cancer and related death. N Engl J Med. 2022; 387:1547–1556. PMID:

36214590.

51. van den Berg DM, Nascimento de Lima P, Knudsen AB, Rutter CM, Weinberg D, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, et al. NordICC trial results in line with expected colorectal cancer mortality reduction after colonoscopy: a modeling study. Gastroenterology. 2023; 165:1077–1079. PMID:

37454978.

52. Forsberg A, Westerberg M, Metcalfe C, Steele R, Blom J, Engstrand L, et al. Once-only colonoscopy or two rounds of faecal immunochemical testing 2 years apart for colorectal cancer screening (SCREESCO): preliminary report of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022; 7:513–521. PMID:

35298893.

53. Sekiguchi M, Westerberg M, Ekbom A, Hultcrantz R, Forsberg A. Detection rates of colorectal neoplasia during colonoscopies and their associated factors in the SCREESCO study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022; 37:2120–2130. PMID:

36062316.

54. Stromberg U, Bonander C, Westerberg M, Levin LA, Metcalfe C, Steele R, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with fecal immunochemical testing or primary colonoscopy: an analysis of health equity based on a randomised trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2022; 47:101398. PMID:

35480071.

55. Park JS, Lee KG, Kim MK. Trends and outcomes of emergency general surgery in elderly and highly elderly population in a single regional emergency center. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2023; 104:325–331. PMID:

37337605.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download