1. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kang MJ, Kong HJ, Im JS, Seo HG. Prediction of cancer incidence and mortality in Korea, 2022. Cancer Res Treat. 2022; 54(2):345–351. PMID:

35313101.

2. Culp MB, Soerjomataram I, Efstathiou JA, Bray F, Jemal A. recent global patterns in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates. Eur Urol. 2020; 77(1):38–52. PMID:

31493960.

3. Eapen RS, Herlemann A, Washington SL 3rd, Cooperberg MR. Impact of the United States Preventive Services Task Force ‘D’ recommendation on prostate cancer screening and staging. Curr Opin Urol. 2017; 27(3):205–209. PMID:

28221220.

4. Center MM, Jemal A, Lortet-Tieulent J, Ward E, Ferlay J, Brawley O, et al. International variation in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates. Eur Urol. 2012; 61(6):1079–1092. PMID:

22424666.

5. Pinsky PF, Prorok PC, Yu K, Kramer BS, Black A, Gohagan JK, et al. Extended mortality results for prostate cancer screening in the PLCO trial with median follow-up of 15 years. Cancer. 2017; 123(4):592–599. PMID:

27911486.

6. Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Zappa M, Nelen V, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014; 384(9959):2027–2035. PMID:

25108889.

7. Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, Bibbins-Domingo K, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018; 319(18):1901–1913. PMID:

29801017.

8. Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, Etzioni R, Freedland SJ, Greene KL, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 2013; 190(2):419–426. PMID:

23659877.

9. Kitagawa Y, Namiki M. Prostate-specific antigen-based population screening for prostate cancer: current status in Japan and future perspective in Asia. Asian J Androl. 2015; 17(3):475–480. PMID:

25578935.

10. Pyun JH, Kang SH, Kim JY, Shin JE, Jeong IG, Kim JW, et al. Survey results on the perception of prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer screening among the general public. Korean J Urol Oncol. 2020; 18(1):40–46.

11. Shim BY. Cancer screening guidelines in Korea. Korean J Med. 2016; 90(3):224–230.

12. Lee HY, Kim DK, Doo SW, Yang WJ, Song YS, Lee B, et al. Time trends for prostate cancer incidence from 2003 to 2013 in South Korea: an age-period-cohort analysis. Cancer Res Treat. 2020; 52(1):301–308. PMID:

31401823.

13. O’Connor A, Jacobsen M. Workbook on Developing and Evaluating Patient Decision Aids. Ottawa: Ottawa Health Research Institute;2003.

14. O’Connor AM, Bennett C, Stacey D, Barry MJ, Col NF, Eden KB, et al. Do patient decision aids meet effectiveness criteria of the international patient decision aid standards collaboration? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Decis Making. 2007; 27(5):554–574. PMID:

17873255.

15. Committee for Establishment of the Guidelines on Screening for Prostate Cancer. Japanese Urological Association. Updated Japanese Urological Association Guidelines on prostate-specific antigen-based screening for prostate cancer in 2010. Int J Urol. 2010; 17(10):830–838. PMID:

20825509.

16. Tchuente V, Giguere AM, Boulanger J. Prostate Cancer Screening- Choosing Whether or Not to Screen. Québec: Université Laval;2019.

21. Yeo Y, Shin DW, Lee J, Han K, Park SH, Jeon KH, et al. Personalized 5-year prostate cancer risk prediction model in Korea based on nationwide representative data. J Pers Med. 2021; 12(1):2. PMID:

35055319.

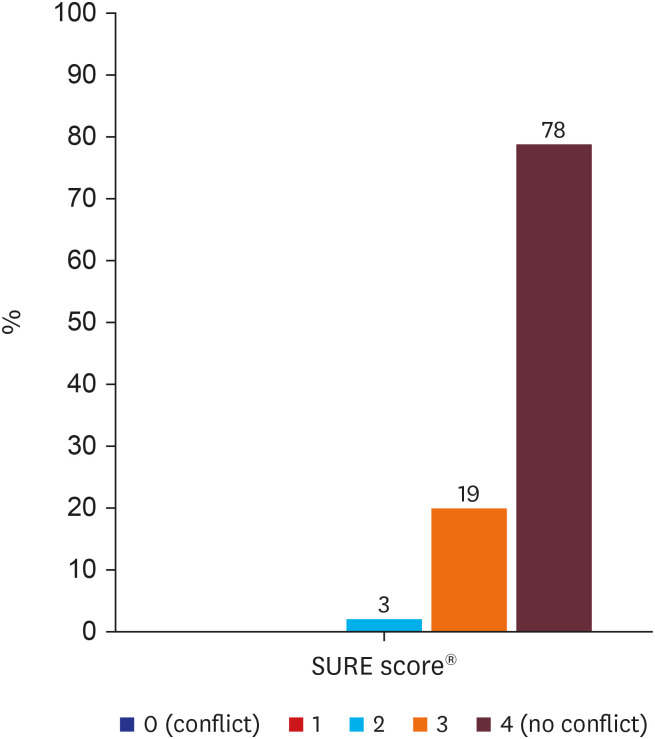

22. Légaré F, Kearing S, Clay K, Gagnon S, D’Amours D, Rousseau M, et al. Are you SURE?: Assessing patient decisional conflict with a 4-item screening test. Can Fam Physician. 2010; 56(8):e308–e314. PMID:

20705870.

23. Bennett C, Graham ID, Kristjansson E, Kearing SA, Clay KF, O’Connor AM. Validation of a preparation for decision making scale. Patient Educ Couns. 2010; 78(1):130–133. PMID:

19560303.

24. Barry MJ, Wexler RM, Brackett CD, Sepucha KR, Simmons LH, Gerstein BS, et al. Responses to a decision aid on prostate cancer screening in primary care practices. Am J Prev Med. 2015; 49(4):520–525. PMID:

25960395.

25. Ruthman JL, Ferrans CE. Efficacy of a video for teaching patients about prostate cancer screening and treatment. Am J Health Promot. 2004; 18(4):292–295. PMID:

15011928.

26. Sheridan SL, Felix K, Pignone MP, Lewis CL. Information needs of men regarding prostate cancer screening and the effect of a brief decision aid. Patient Educ Couns. 2004; 54(3):345–351. PMID:

15324986.

27. Frencher SK Jr, Sharma AK, Teklehaimanot S, Wadzani D, Ike IE, Hart A, et al. PEP talk: prostate education program, “Cutting through the uncertainty of prostate cancer for black men using decision support instruments in barbershops”. J Cancer Educ. 2016; 31(3):506–513. PMID:

26123763.

28. Valente TW, Paredes P, Poppe PR. Matching the message to the process: the relative ordering of knowledge, attitudes, and practices in behavior change research. Hum Commun Res. 1998; 24(3):366–385. PMID:

12293436.

29. Kim S, Shin DW, Yang HK, Kim SY, Ko YJ, Cho B, et al. Public perceptions on cancer incidence and survival: a nation-wide survey in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2016; 48(2):775–788. PMID:

26044162.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download