Abstract

Purpose

Because the global geriatric population continues to increase, the assessment of emergency surgical outcomes in elderly patients with acute peritonitis will become more important.

Methods

A retrospective review was conducted on the data of 174 elderly patients who underwent emergency surgery for intestinal perforation or intestinal infarction between June 2010 and November 2022. We conducted an analysis of the risk factors associated with postoperative complications and mortality by evaluating the characteristics of patients and their surgical outcomes.

Results

In our study, most patients (94.3%) had preexisting comorbidities, and many patients (84.5%) required transfer to the intensive care unit following emergency surgery. Postoperative complications were observed in 84 individuals (48.3%), with postoperative mortality occurring in 29 (16.7%). Multivariate analysis revealed preoperative acute renal injury, hypoalbuminemia, and postoperative ventilator support as significant predictors of postoperative mortality.

Conclusion

When elderly patients undergo emergency surgery for intestinal perforation or infarction, it is important to recognize that those with preoperative acute renal injury, hypoalbuminemia, and a need for postoperative ventilator support have a poor prognosis. Therefore, these patients require intensive care from the early stages of treatment.

The increase in the elderly population is due to a combination of factors, including risk factor reduction through primary prevention, early national cancer screening, management of acute diseases, and improvement of medical care [1]. Consequently, the increase in the elderly population has led to an increase in the number of emergency surgeries among elderly individuals [2]. Furthermore, elderly patients are more vulnerable to postoperative complications and mortality [3456].

The aging process may result in a gradual loss of reserve capacity, even in individuals without comorbidities [7]. Age of >70 years has been reported as an independent predictor of postoperative complications, hospital mortality, and prolonged hospital stays [8]. In elective surgery, the medical staff, including surgeons, evaluate the preoperative risk stratification for elderly patients and establish a treatment plan based on the risk assessment. Meticulous surgical preparation and planning are crucial factors for improving surgical outcomes in elderly patients.

Conversely, it is difficult for a surgeon to evaluate and manage patient comorbidities prior to emergency surgery. In several reports, emergency surgery in elderly patients was associated with high rates of postoperative complication and mortality [24910]. One limitation of these studies is that the distribution of patients was not uniform, as it included those with favorable surgical outcomes such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, and nonobstructive bowel ischemia.

Peritonitis is a frequently encountered cause of acute inflammation of the peritoneum in surgical patients. In particular, generalized peritonitis due to gastrointestinal infarction or perforation poses a significant risk to the patient’s life.

Therefore, the present study aimed to analyze prognostic factors for postoperative complications and mortality in elderly patients who underwent emergency surgery for bowel perforation or irreversible bowel ischemia.

The Institutional Review Board of Hanyang University Guri Hospital approved this study (No. 2023-07-026). This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and written informed consent was waived due to its retrospective nature.

We retrospectively reviewed and prospectively collected data on 174 elderly patients who underwent emergency surgery for bowel perforation or irreversible intestinal ischemia performed by a single surgeon between June 2010 and December 2022 at Hanyang University Guri Hospital. In this study, elderly patients were defined as those aged 70 years or older. Patients who underwent emergency surgery for appendicitis, diverticulitis, cholecystitis, or reversible intestinal ischemia regardless of strangulation were excluded from this study because the surgical risk was lower and the surgical outcome better. Laparoscopic surgery was performed by a surgeon with extensive experience in laparoscopic surgery for peritonitis.

In this study, intestinal perforation was defined as the presence of a visible perforation during surgery.

Irreversible intestinal ischemia refers to a condition of sustained lack of blood supply to the intestine, leading to irreversible tissue damage. After removing the underlying cause of ischemic injury, the viability of the bowel was confirmed through an observation period of at least 15 minutes. The viability of the bowel was primarily assessed based on criteria such as restoration of black-to-pink color, arterial pulsations, and visible peristalsis.

In this study, shock was defined as low blood pressure (systolic blood pressure, <90 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure, <60 mmHg) in the emergency room. Acute kidney injury (AKI) was defined as an increase in serum creatinine of ≥0.3 mg/dL or ≥50% within 48 hours or urine output of <0.5 mL/kg/hr for >6 hours [11].

Decisions regarding postoperative admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) were made by the surgeon and anesthesiologist involved in the procedure. Patients admitted to the ICU received intensive care from licensed specialists in the field of critical care medicine.

The surgeon involved in this study had extensive experience in laparoscopic surgery in patients with panperitonitis. The experience included selective gastric cancer surgery and complicated emergency surgeries [1213141516].

We performed laparoscopic surgery with the anesthesiologist’s consent after carefully assessing the patient’s condition. The major contraindication to laparoscopic surgery is uncontrolled hemodynamic instability. However, in some patients who had low blood pressure on arrival, laparoscopic surgery was performed if their blood pressure returned to normal after aggressive resuscitation.

The clinical data obtained from medical records were age, sex, body mass index, history of major abdominal surgeries, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASA PS) classification, time from symptom onset to surgery, presence of shock upon admission, and mental status.

The anesthesiologist assessed the ASA PS classification immediately before surgery. Preoperative serum albumin and hemoglobin levels were measured on the patient admission to the emergency department. Hypoalbuminemia was defined as a reduction in serum albumin level to below the normal range (<3.5 g/dL).

Early surgical outcomes included operative time, postoperative complications, postoperative mortality, and length of hospital stay after surgery. Because elderly patients have many comorbidities, postoperative complications were divided into 2 categories: complication associated with surgery (CAS) and complication not associated with surgery (CNAS). CNAS was defined as a complication arising from an underlying systemic condition in the patient that was unrelated to the surgical procedure. This classification has been utilized in a similar manner in several research papers [1718].

Postoperative surgical complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. Postoperative mortality was defined as any death, regardless of cause, that occurred within 30 days after surgery [19].

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21 (IBM Corp.). All values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test, and continuous variables were analyzed with the Student t-test depending on the data. Multivariate analysis was performed to identify risk factors associated with early surgical outcomes. Factors with relatively small P-values (P < 0.1) in univariate analysis were selected as variables in multivariate analysis performed using multiple logistic regression analysis. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals were estimated for each variable in the multivariate analysis. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

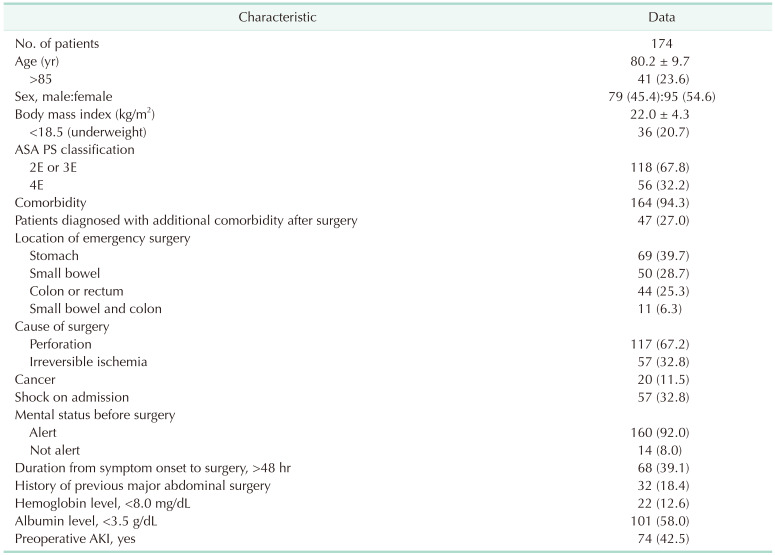

During the 12-year study period, 174 elderly patients underwent emergency surgery for intestinal perforation or irreversible intestinal ischemia. Patient demographic data and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Nearly all elderly patients (94.3%) had comorbidities and 56 patients had an ASA PS grade 4E. One-third of the patients were newly diagnosed with comorbidities after emergency surgery. Among the patients, 57 (32.8%) were in a state of shock before surgery and 14 (8.0%) had a lower than alert mental status. Furthermore, 68 patients (39.1%) arrived at the hospital more than 48 hours after the onset of symptoms.

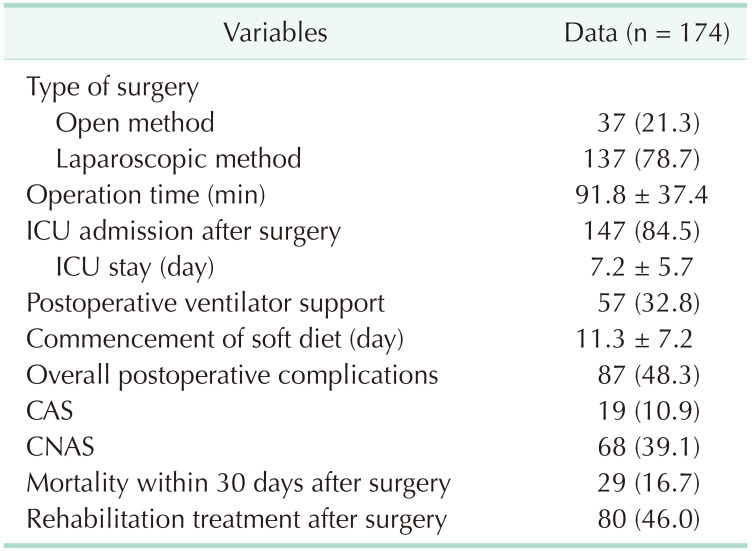

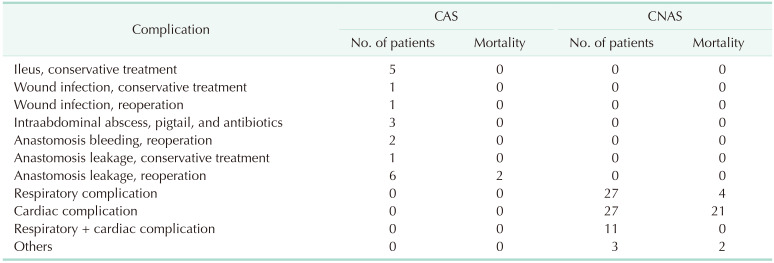

Among the 174 patients, 137 (78.7%) underwent laparoscopic surgery with an average duration of 91.8 minutes; 147 (84.5%) were transferred to the ICU after surgery and the average length of stay in the ICU was 7.2 days. Among the patients transferred to the ICU, 57 (32.8%) required ventilators. Postoperative complications occurred in 87 patients; 19 had complications directly related to the surgery and 68 developed complications associated with their systemic conditions. Twenty-nine patients (16.7%) died within 30 days of surgery (Table 2).

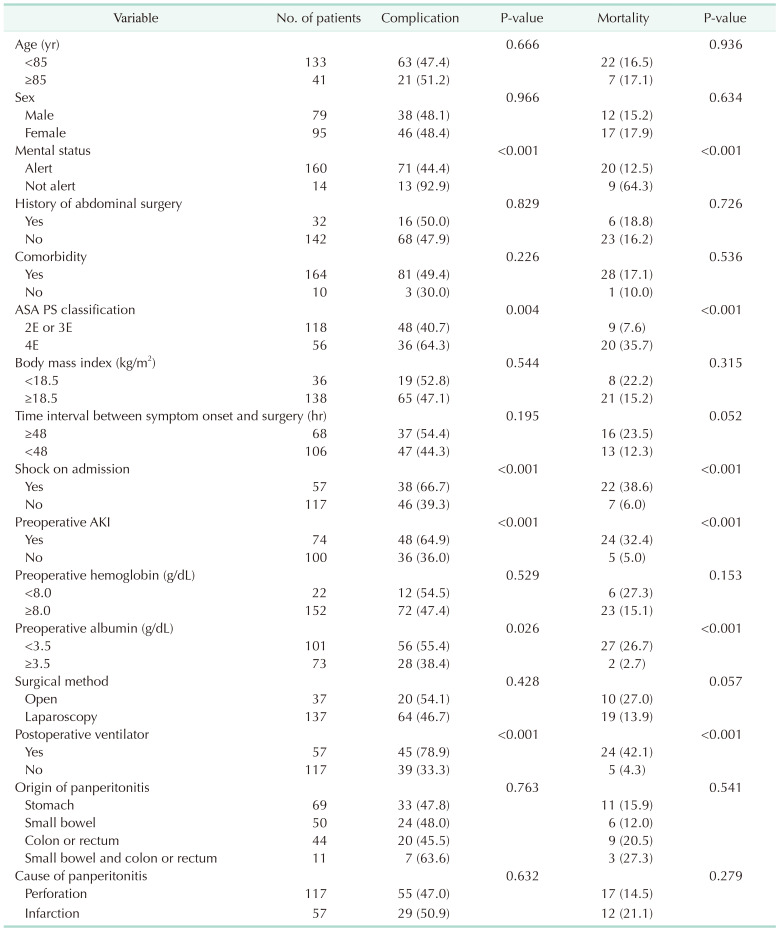

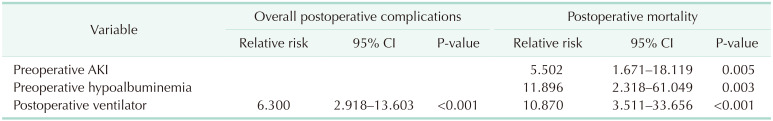

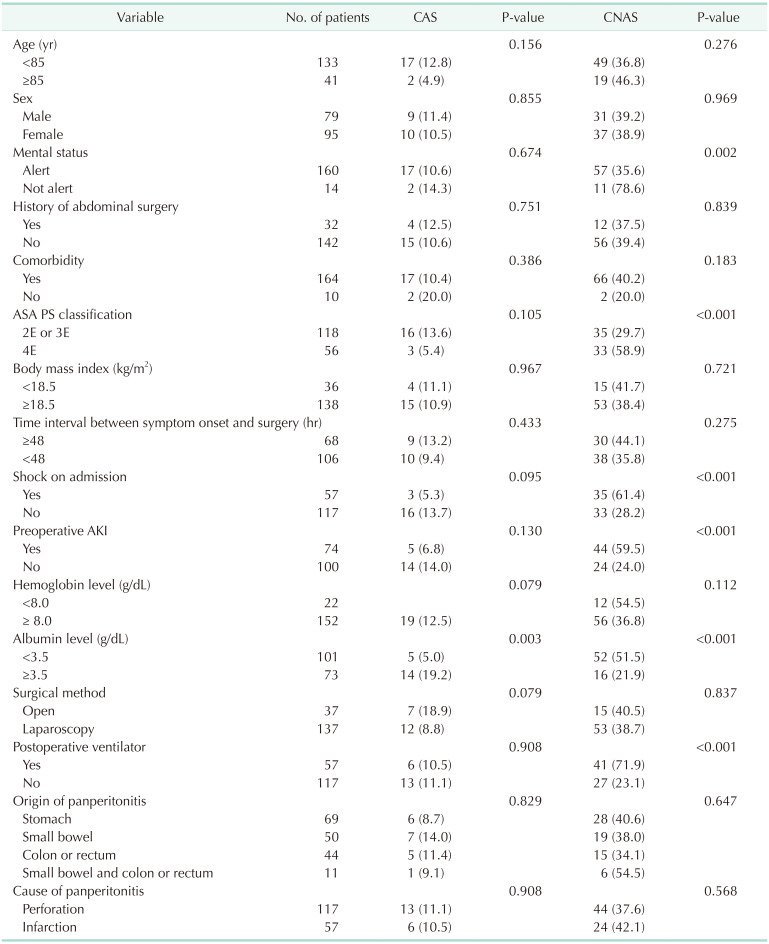

Tables 3 and 4 present the results of univariate analysis regarding risk factors associated with postoperative complications and mortality. Postoperative complications occurred significantly more frequently in patients who experienced deterioration of mental status, higher ASA PS grade (4E), state of shock on admission, occurrence of AKI, low serum albumin level, and requirement for postoperative ventilator support. Postoperative mortality within 30 days was higher in patients with deteriorating mental status, higher ASA PS grade (4E), state of shock on admission, AKI, low serum albumin level, or requirement for postoperative ventilator support. CAS occurred significantly more often only in patients with hypoalbuminemia. CNAS occurred more often in patients with deteriorating mental status, higher ASA PS grade (4E), state of shock on admission, AKI, low serum albumin level, or requirement for postoperative ventilator support.

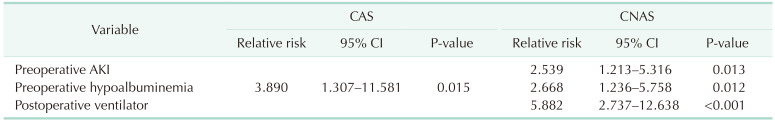

Tables 5 and 6 present the results of multivariate analysis regarding risk factors associated with postoperative complications and mortality. Postoperative complications were higher in patients requiring postoperative ventilator support. Patients who died within 30 days of surgery were more likely to have AKI or hypoalbuminemia or to require postoperative ventilator support. CAS occurred significantly more often in patients with hypoalbuminemia. CNAS occurred significantly more often in patients with AKI, hypoalbuminemia, and the need for postoperative ventilator support.

There was a total of 19 cases of CAS. Anastomosis leakage occurred in 9 patients, and 2 of them died due to complications. Two patients required reoperation due to bleeding at the site of anastomosis, and 3 patients developed an intra-abdominal abscess. Additionally, postoperative ileus occurred in 5 patients.

CNAS was observed in 68 of 84 elderly patients who developed postoperative complications; 64 of them experienced respiratory or cardiac complications. Among the 29 deaths, 21 (72.4%) were attributed to cardiac complications.

Life expectancy continues to increase worldwide [1], and the interest in geriatric patients is growing. With the increasing number of emergency surgeries performed on the elderly, there is a heightened interest in identifying preoperative risk factors and evaluating surgical outcomes. A review of several studies confirms a high prevalence of comorbidities among elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery [2420]. Our study also confirmed a significantly high comorbidity rate (94.3%). Specifically, 47 patients (27.0%) were newly diagnosed with chronic diseases after emergency surgery.

In several studies, the presence of underlying chronic comorbidity had a significant negative effect on postoperative complications and mortality in elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery [24910]. However, our findings did not indicate comorbidity in elderly patients as a significant risk factor for postoperative complications and mortality. Notably, most patients (>90%) included in this study had preexisting comorbidities, which may have made it challenging to obtain statistically significant results. Therefore, the results of this study do not indicate whether comorbidity affects the outcome of emergency surgery in elderly patients.

Several studies have explained why advances in medical technology and appropriate management of underlying comorbidities over the past decades have shown decreased effects on emergency surgical outcomes in elderly patients [221]. However, our opinion differs from that presented in a previous paper. Based on our results (Table 7), most deaths were caused by CNAS. Specifically, there appears to be a significant incidence of cardiac-related complications, which indirectly suggests that the overall health conditions of elderly patients influence prognosis. Our results also indicated that elderly patients have a higher incidence of cardiorespiratory complications after emergency surgery, which may be attributed to age-related decline in cardiac and lung function. We hypothesized that elderly patients have a high mortality rate due to their impaired recovery from cardiovascular complications following emergency surgery. Therefore, factors other than presence or absence of chronic diseases must be considered. Future studies should reevaluate the effects of chronic diseases on postoperative complications in elderly patients considering the severity of these diseases and the overall systemic condition.

When analyzing the preoperative characteristics of elderly patients in this study, a significant number of patients who underwent emergency surgery presented at the hospital with ASA PS grade 4E (patients with severe systemic disease that poses a constant threat to life) and in a state of shock. Furthermore, approximately half of the patients presented with hypoalbuminemia and acute renal injury upon arrival at the emergency department. Hypoalbuminemia is a well-recognized risk factor for surgical outcomes in many studies. Our study also demonstrated the significance of hypoalbuminemia as a predictor of postoperative mortality. Several studies have suggested serum albumin as a significant marker of the patient’s nutritional status and an indicator of inflammatory metabolism [22232425]. AKI has recently replaced the term acute renal failure. Patients with AKI may develop the condition due to a combination of reduced blood flow, such as ischemia and sepsis [262728], and can progress to organ dysfunction. Our study emphasizes AKI as a significant risk factor for postoperative mortality.

Most patients in our study were transferred to the ICU following emergency surgery, and many required postoperative ventilators support. Among the total number of patients, CNAS was observed in 68 (39.1%) and CAS in 19 (10.9%). A total of 29 elderly patients died within 30 days of surgery. Compared with previous studies [24910], we demonstrate similar or lower rates of complications (48.3%) and mortality (16.7%) despite including a significant number of critically ill patients. Utilization of the ICU after surgery and the involvement of ICU specialists likely contributed to the favorable outcome.

Based on our findings, we propose the following observations. First, in elderly patients with intestinal perforation and intestinal necrosis, preoperative hypoalbuminemia and AKI were significant negative factors for postoperative prognosis. Therefore, intensive management from the beginning of treatment is crucial. Second, many elderly patients required mechanical ventilation support after surgery. Due to their poor prognosis, it is crucial to involve a critical care specialist from the early stages of treatment. Third, the occurrence of cardiac-related complications after emergency surgery was associated with high mortality rates in elderly patients. Therefore, it is essential to adopt an active treatment approach that includes consultation with a cardiologist after emergency surgery in elderly patients.

This study had certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Specifically, it was a retrospective study, which makes it susceptible to selection bias. Nevertheless, the incidence and types of complications were consistent with previous studies. To validate the outcomes and extend applicability to a broader range of individuals, further investigations with larger sample sizes and more diverse patient cohorts are warranted.

Our study results revealed that most patients who experienced postoperative complications and mortality were affected by CNAS. Therefore, patients with preoperative AKI, hypoalbuminemia, or requiring postoperative ventilator support have a very poor prognosis, including mortality. Furthermore, it is crucial to raise awareness among both patients and their families regarding these risk factors.

References

1. Crimmins EM, Beltrán-Sánchez H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011; 66:75–86. PMID: 21135070.

2. Fukuda N, Wada J, Niki M, Sugiyama Y, Mushiake H. Factors predicting mortality in emergency abdominal surgery in the elderly. World J Emerg Surg. 2012; 7:12. PMID: 22578159.

3. Lin HS, Watts JN, Peel NM, Hubbard RE. Frailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2016; 16:157. PMID: 27580947.

4. Arenal JJ, Bengoechea-Beeby M. Mortality associated with emergency abdominal surger y in the elderly. Can J Surg. 2003; 46:111–116. PMID: 12691347.

5. Cook TM, Day CJ. Hospital mortality after urgent and emergency laparotomy in patients aged 65 yr and over. Risk and prediction of risk using multiple logistic regression analysis. Br J Anaesth. 1998; 80:776–781. PMID: 9771307.

6. Ford PN, Thomas I, Cook TM, Whitley E, Peden CJ. Determinants of outcome in critically ill octogenarians after surgery: an observational study. Br J Anaesth. 2007; 99:824–829. PMID: 17959590.

7. Evers BM, Townsend CM, Thompson JC. Organ physiology of aging. Surg Clin North Am. 1994; 74:23–39. PMID: 8108769.

8. Polanczyk CA, Marcantonio E, Goldman L, Rohde LE, Orav J, Mangione CM, et al. Impact of age on perioperative complications and length of stay in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2001; 134:637–643. PMID: 11304103.

9. Green G, Shaikh I, Fernandes R, Wegstapel H. Emergency laparotomy in octogenarians: a 5-year study of morbidity and mortality. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013; 5:216–221. PMID: 23894689.

10. Park SY, Chung JS, Kim SH, Kim YW, Ryu H, Kim DH. The safety and prognostic factors for mortality in extremely elderly patients undergoing an emergency operation. Surg Today. 2016; 46:241–247. PMID: 25788220.

11. Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007; 11:R31. PMID: 17331245.

12. Kim HI, Kim MG. Entirely laparoscopic gastrectomy and colectomy for remnant gastric cancer with gastric out let obstruct ion and transverse colon invasion. J Gastric Cancer. 2015; 15:286–289. PMID: 26819808.

13. Kim MG. Laparoscopic surgery for perforated duodenal ulcer disease: analysis of 70 consecutive cases from a single surgeon. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015; 25:331–336. PMID: 25799260.

14. Ma CH, Kim MG. Laparoscopic primary repair with omentopexy for duodenal ulcer perforation: a single institution experience of 21 cases. J Gastric Cancer. 2012; 12:237–242. PMID: 23346496.

15. Kim MG, Park HK, Park JJ, Lee HG, Nam YS. The applicability of laparoscopic gastrectomy in the surgical treatment of giant duodenal ulcer perforation. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012; 22:122–126. PMID: 22487624.

16. Kim MG, Kim KC, Yook JH, Kim BS, Kim TH, Kim BS. A practical way to overcome the learning period of laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25:3838–3844. PMID: 21656323.

17. Schumacher MC, Jonsson MN, Hosseini A, Nyberg T, Poulakis V, Pardalidis NP, et al. Surgery-related complications of robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal urinary diversion. Urology. 2011; 77:871–876. PMID: 21256563.

18. Wijffels MM, Hagenaars T, Latifi D, Van Lieshout EM, Verhofstad MH. Early results after operatively versus non-operatively treated flail chest: a retrospective study focusing on outcome and complications. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020; 46:539–547. PMID: 29785655.

19. Clavien PA, Strasberg SM. Severity grading of surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2009; 250:197–198. PMID: 19638901.

20. Fenyö G. Acute abdominal disease in the elderly: experience from two series in Stockholm. Am J Surg. 1982; 143:751–754. PMID: 7091511.

21. Rix TE, Bates T. Pre-operative risk scores for the prediction of outcome in elderly people who require emergency surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2007; 2:16. PMID: 17550623.

22. Vincent JL, Dubois MJ, Navickis RJ, Wilkes MM. Hypoalbuminemia in acute illness: is there a rationale for intervention? A meta-analysis of cohort studies and controlled trials. Ann Surg. 2003; 237:319–334. PMID: 12616115.

23. Vincent JL. Relevance of albumin in modern critical care medicine. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2009; 23:183–191. PMID: 19653438.

24. van Stijn MF, Korkic-Halilovic I, Bakker MS, van der Ploeg T, van Leeuwen PA, Houdijk AP. Preoperative nutrition status and postoperative outcome in elderly general surgery patients: a systematic review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013; 37:37–43. PMID: 22549764.

25. Kang SC, Kim HI, Kim MG. Low serum albumin level, male sex, and total gastrectomy are risk factors of severe postoperative complications in elderly gastric cancer patients. J Gastric Cancer. 2016; 16:43–50. PMID: 27104026.

26. Makris K, Spanou L. Acute kidney injury: definition, pathophysiology and clinical phenotypes. Clin Biochem Rev. 2016; 37:85–98. PMID: 28303073.

27. Sharfuddin AA, Molitoris BA. Pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011; 7:189–200. PMID: 21364518.

28. Gomez H, Ince C, De Backer D, Pickkers P, Payen D, Hotchkiss J, et al. A unified theory of sepsis-induced acute kidney injury: inflammation, microcirculatory dysfunction, bioenergetics, and the tubular cell adaptation to injury. Shock. 2014; 41:3–11.

Table 3

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors for overall postoperative complications and mortality

Table 5

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for overall postoperative complications and mortality

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download