1. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999; 56(3):303–308. PMID:

10190820.

2. Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, Cahn-Weiner D, Decarli C. MCI is associated with deficits in everyday functioning. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006; 20(4):217–223. PMID:

17132965.

3. Perneczky R, Pohl C, Sorg C, Hartmann J, Tosic N, Grimmer T, et al. Impairment of activities of daily living requiring memory or complex reasoning as part of the MCI syndrome. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006; 21(2):158–162. PMID:

16416470.

4. Gold DA. An examination of instrumental activities of daily living assessment in older adults and mild cognitive impairment. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012; 34(1):11–34. PMID:

22053873.

5. Jekel K, Damian M, Wattmo C, Hausner L, Bullock R, Connelly PJ, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and deficits in instrumental activities of daily living: a systematic review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015; 7(1):17. PMID:

25815063.

6. Daly E, Zaitchik D, Copeland M, Schmahmann J, Gunther J, Albert M. Predicting conversion to Alzheimer disease using standardized clinical information. Arch Neurol. 2000; 57(5):675–680. PMID:

10815133.

7. Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, DeCarli C. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic- vs community-based cohorts. Arch Neurol. 2009; 66(9):1151–1157. PMID:

19752306.

8. Farias ST, Lau K, Harvey D, Denny KG, Barba C, Mefford AN. Early functional limitations in cognitively normal older adults predict diagnostic conversion to mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017; 65(6):1152–1158. PMID:

28306147.

9. Tomaszewski Farias S, Giovannetti T, Payne BR, Marsiske M, Rebok GW, Schaie KW, et al. Self-perceived difficulties in everyday function precede cognitive decline among older adults in the ACTIVE Study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018; 24(1):104–112. PMID:

28797312.

10. Sikkes SA, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Pijnenburg YA, Scheltens P, Uitdehaag BM. A systematic review of instrumental activities of daily living scales in dementia: room for improvement. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009; 80(1):7–12. PMID:

19091706.

11. Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Cahn-Weiner D, Jagust W, Baynes K, et al. The measurement of Everyday Cognition (ECog): scale development and psychometric properties. Neuropsychology. 2008; 22(4):531–544. PMID:

18590364.

12. Farias ST, Park LQ, Harvey DJ, Simon C, Reed BR, Carmichael O, et al. Everyday cognition in older adults: associations with neuropsychological performance and structural brain imaging. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2013; 19(4):430–441. PMID:

23369894.

13. Rueda AD, Lau KM, Saito N, Harvey D, Risacher SL, Aisen PS, et al. Self-rated and informant-rated everyday function in comparison to objective markers of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015; 11(9):1080–1089. PMID:

25449531.

14. Hsu JL, Hsu WC, Chang CC, Lin KJ, Hsiao IT, Fan YC, et al. Everyday cognition scales are related to cognitive function in the early stage of probable Alzheimer’s disease and FDG-PET findings. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1):1719. PMID:

28496183.

15. Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Jack CR Jr, Jagust WJ, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw L, et al. The Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative: progress report and future plans. Alzheimers Dement. 2010; 6(3):202–11.e7. PMID:

20451868.

16. Schinka JA. Use of informants to identify mild cognitive impairment in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010; 12(1):4–12. PMID:

20425304.

17. Lau KM, Parikh M, Harvey DJ, Huang CJ, Farias ST. Early cognitively based functional limitations predict loss of independence in instrumental activities of daily living in older adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2015; 21(9):688–698. PMID:

26391766.

18. Park LQ, Harvey D, Johnson J, Farias ST. Deficits in everyday function differ in AD and FTD. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015; 29(4):301–306. PMID:

25590940.

19. Williams JK, Kim JI, Downing N, Farias S, Harrington DL, Long JD, et al. Everyday cognition in prodromal Huntington disease. Neuropsychology. 2015; 29(2):255–267. PMID:

25000321.

20. Cooper RA, Benge J, Lantrip C, Soileau MJ. The Everyday Cognition scale in Parkinson’s disease. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2017; 30(3):265–267. PMID:

28670053.

21. van Harten AC, Mielke MM, Swenson-Dravis DM, Hagen CE, Edwards KK, Roberts RO, et al. Subjective cognitive decline and risk of MCI: the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology. 2018; 91(4):e300–e312. PMID:

29959257.

22. Shokouhi S, Conley AC, Baker SL, Albert K, Kang H, Gwirtsman HE, et al. The relationship between domain-specific subjective cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s pathology in normal elderly adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2019; 81:22–29. PMID:

31207466.

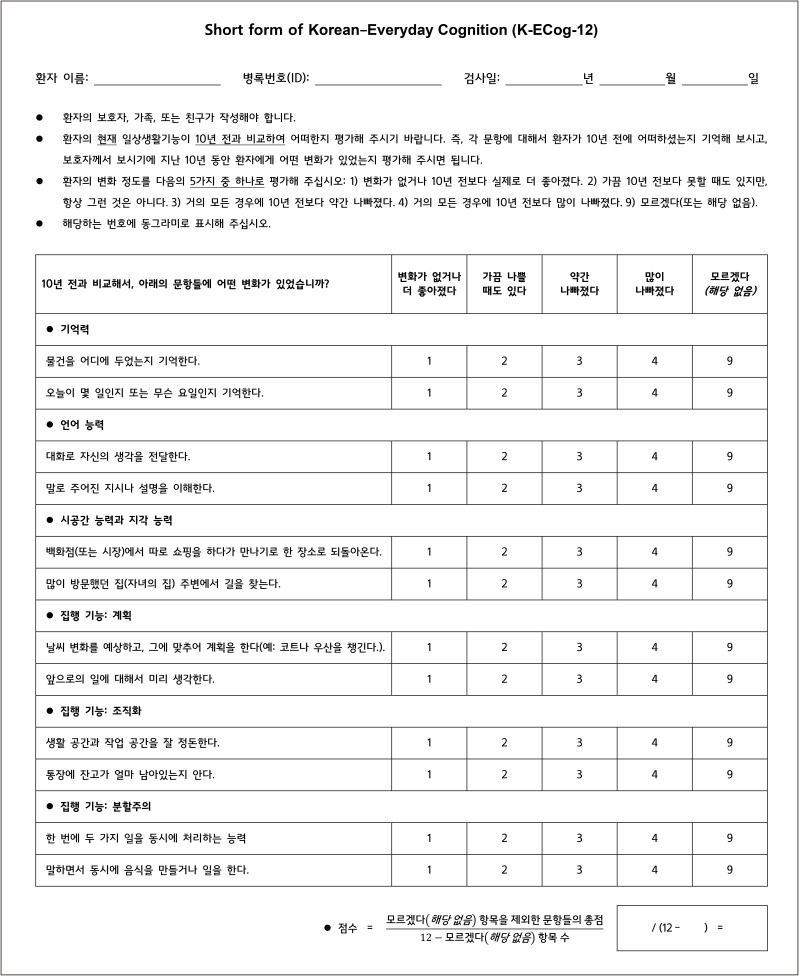

23. Song M, Lee SH, Kim SY, Kang Y. Measurement of Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD) using Korean-Everyday Cognition (K-ECog) as a screening tool: a feasibility study. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2021; 20(4):80–88. PMID:

34795771.

24. Tomaszewski Farias S, Mungas D, Harvey DJ, Simmons A, Reed BR, Decarli C. The measurement of everyday cognition: development and validation of a short form of the Everyday Cognition scales. Alzheimers Dement. 2011; 7(6):593–601. PMID:

22055976.

25. Song M, Lee SH, Jahng S, Kim SY, Kang Y. Validation of the Korean-Everyday Cognition (K-ECog). J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34(9):e67. PMID:

30863265.

26. Ho S, Hong YJ, Jeong JH, Park KH, Kim S, Wang MJ, et al. Study design and baseline results in a cohort study to identify predictors for the clinical progression to mild cognitive impairment or dementia from Subjective Cognitive Decline (CoSCo) study. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2022; 21(4):147–161. PMID:

36407288.

27. Ryu SY, Hong YJ, Ho S, Jeong JH, Park KH, Kim S, et al. Subtle cognitive deficits are associated with amyloid-β positivity, but not severity of self-reported decline: results from the CoSCo study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2022; 51(2):159–167. PMID:

35381591.

28. Christensen KJ, Moye J, Armson RR, Kern TM. Health screening and random recruitment for cognitive aging research. Psychol Aging. 1992; 7(2):204–208. PMID:

1610509.

29. Kang Y. A normative study of the Korean-Mini Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in the elderly. Korean J Psychol Gen. 2006; 25(2):1–12.

30. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, TX, USA: American Psychiatric Association;2013.

31. Ye BS, Seo SW, Cho H, Kim SY, Lee JS, Kim EJ, et al. Effects of education on the progression of early- versus late-stage mild cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013; 25(4):597–606. PMID:

23207181.

32. Chin J, Park J, Yang SJ, Yeom J, Ahn Y, Baek MJ, et al. Re-standardization of the Korean-Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL): clinical usefulness for various neurogenerative diseases. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2018; 17(1):11–22. PMID:

30906387.

33. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993; 43(11):2412–2414.

34. Kang Y, Park J, Yu KH, Lee BC. A reliability, validity, and normative study of the Korean-Montreal Cognitive Assessment (K-MoCA) as an instrument for screening of vascular cognitive impairment (VCI). Korean J Clin Psychol. 2009; 28(2):549–562.

35. Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982; 139(9):1136–1139. PMID:

7114305.

36. Bae JN, Cho MJ. Development of the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J Psychosom Res. 2004; 57(3):297–305. PMID:

15507257.

37. Muraki E. A generalized partial credit model: application of an EM algorithm. ETS Res Rep Ser. 1992; 1992(1):i-30.

38. Taber KS. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ. 2018; 48(6):1273–1296.

39. Simundic AM. Diagnostic accuracy—part 1: basic concepts: sensitivity and specificity, ROC analysis, STARD Statement. Point Care. 2012; 11(1):6–8.

40. Dannhauser TM, Walker Z, Stevens T, Lee L, Seal M, Shergill SS. The functional anatomy of divided attention in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Brain. 2005; 128(Pt 6):1418–1427. PMID:

15705612.

41. Jefferson AL, Byerly LK, Vanderhill S, Lambe S, Wong S, Ozonoff A, et al. Characterization of activities of daily living in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008; 16(5):375–383. PMID:

18332397.

42. Brown PJ, Devanand DP, Liu X, Caccappolo E. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Functional impairment in elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; 68(6):617–626. PMID:

21646578.

43. Marshall GA, Zoller AS, Kelly KE, Amariglio RE, Locascio JJ, Johnson KA, et al. Everyday cognition scale items that best discriminate between and predict progression from clinically normal to mild cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014; 11(9):853–861. PMID:

25274110.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download