The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is highly infectious and affects the respiratory system. It can cause symptoms ranging from mild respiratory illness to severe pneumonia and in some cases death. The World Health Organization named the disease coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

1 The COVID-19 pandemic has had wide-ranging impacts, affecting not only the physical health of individuals and communities, but also their psychological well-being. Psychological difficulties associated with COVID-19 include trauma and stress-related symptoms, infection fear, depression, anxiety, and suicidality.

234 Fear of contracting COVID-19 is at the core of many of the mental health conditions seen during the pandemic. COVID-19 infection-related fears include fear of body changes, being a potential threat to intimate partners, and economic losses, as well as fears related to unclear information, making choices, and behavioral consequences.

5 Several studies found that fear of COVID-19 mediates and predicts the relationship between the pandemic situation and mental health outcomes.

667810

Fear of COVID-19 infection is particularly significant for healthcare workers (HCWs) due to their increased exposure to viral transmission at the forefront of the battle against the pandemic. HCWs experience heightened COVID-19 infection fear compared to the general population; they are at higher risk of experiencing mental health challenges, which is important because their mental health directly impacts their ability to deliver quality care and maintain the functioning of healthcare systems. It is crucial to prioritize the mental health of HCWs in the era of infectious disease.

Identifying factors associated with the psychological outcomes of COVID-19 infection fear among HCWs is crucial for developing interventions and strategies to mitigate risk in vulnerable groups. Studying multiple variables associated with the fear of COVID-19 infection is crucial for a more comprehensive understanding. Therefore, this study examined the role of working context, demographics, personal characteristics, and prior experiences related to COVID-19. We also explored the association between COVID-19 infection fears and professional quality of life. Several studies have been conducted in this regard in Korea. Cho et al.

11 explored factors affecting nurses’ COVID-19 infection fear; marital status, living with a spouse, living with children, and COVID-19-related work type. Jang et al.

12 suggested that the perceived threat of COVID-19 impacts the intention of whether they continue healthcare work.

This study used an online (Google Forms) questionnaire, administered by the Jeju Mental Health Welfare Center in Jeju, Korea, to collect data on negative psychological states related to COVID-19 (i.e., infection fear, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress). The questionnaire was completed by HCWs in COVID-19 dedicated teams. Data were collected in March 2022, 2 years into the COVID-19 pandemic (during the fifth wave when the spread of COVID-19 peaked). The participants were physicians, nurses, and others involved in healthcare (e.g., public officials, medical laboratory technologists, and radiologists). The participants worked in dedicated COVID-19 hospitals, residential treatment centers, and public health centers in Jeju, Korea. Informed consent was confirmed by clicking on the “start” button on the front page of the online survey. The survey was anonymous, and the confidentiality of the information was assured. In total, 371 HCWs voluntarily participated in the online survey and were recruited through advertisements.

The online survey also collected sociodemographic data, including age, gender, job, and years of healthcare work experience, as well as data related to the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., isolation experience, infection-positive status, and number of years worked during the pandemic). Fear of COVID-19 infection was assessed using the COVID-19 Infection Fear Scale (CIFS) developed by the Korean Society for Traumatic Stress Studies.

13 The CIFS scale consists of nine items scored on a 4-point Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 0 to 27. The Cronbach’s alpha of the CIFS in this study was 0.906.

Professional quality of life was assessed using the Professional Quality of Life Scale 5 (ProQOL-5).

14 The ProQOL-5 has three subscales: compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. The ProQOL-5 includes 30 items scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). The raw subscale scores range from 10 to 50. The compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress subscales had Cronbach’s alphas of 0.93, 0.79, and 0.84, respectively.

The subjects were classified into high (COVID-19 infection fear score ≥ 75th percentile), intermediate (25th percentile ≤ score < 75th percentile), and low (score < 25th percentile) COVID-19 infection fear groups. We compared characteristics associated with COVID-19 infection fear levels among the three groups. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test and continuous variables with analysis of variance and the Scheffé post hoc test. Variables that were significant in the univariate analyses were entered into multivariate logistic regression models. After setting the high COVID-19 infection fear group as the outcome group and the low COVID-19 infection fear group as the reference group, we performed multivariate logistic regression to identify variables independently associated with higher COVID-19 infection fear. Model 1 included demographic factors, such as age and gender. Model 2 added compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress, with adjustment for demographic characteristics. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (ver. 25.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and P values < 0.05 were deemed to indicate statistical significance.

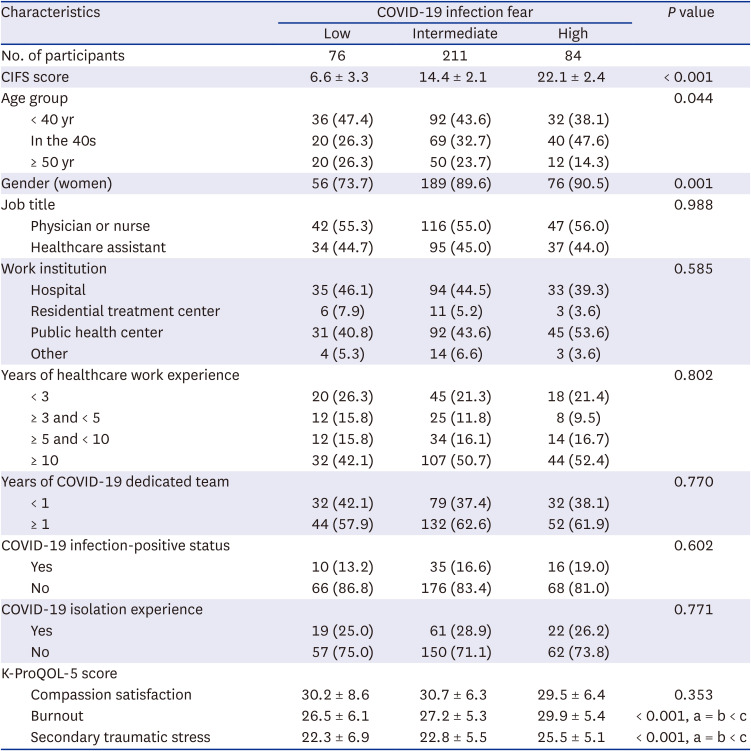

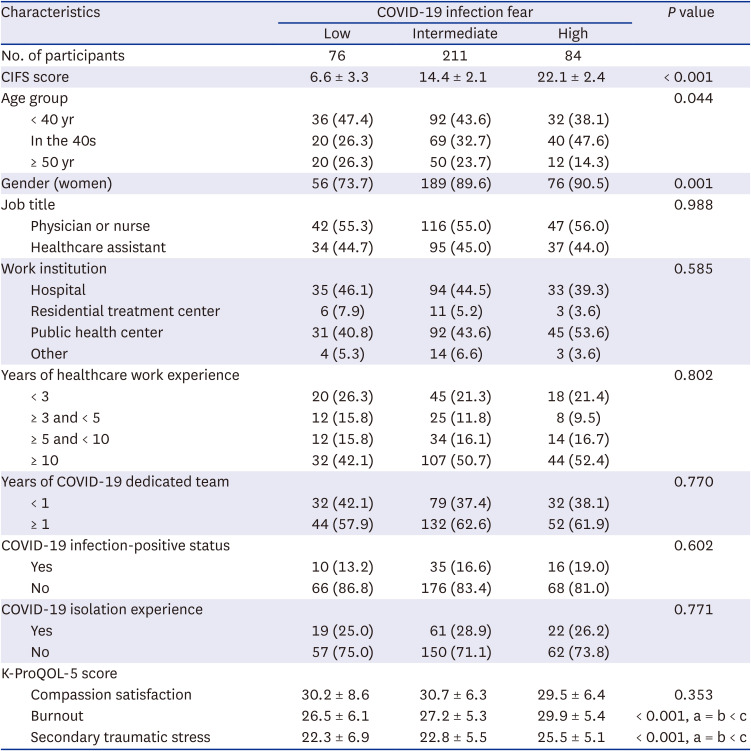

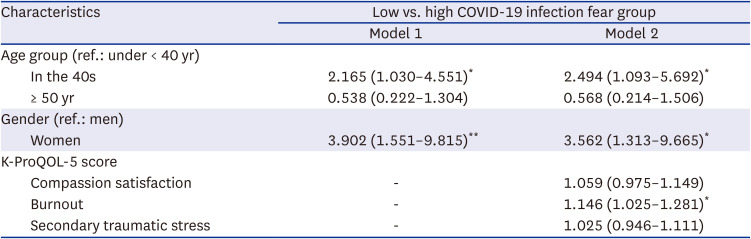

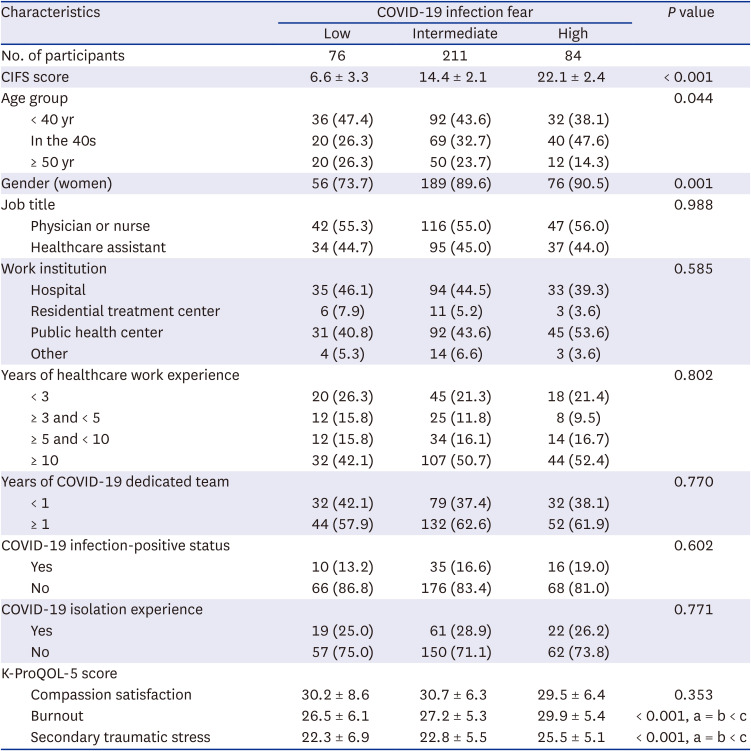

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the low, medium, and high COVID-19 infection fear groups. Age (

P = 0.044) and gender (

P = 0.001) differed significantly among the three groups. The high COVID-19 infection fear group had a significantly greater proportion of women and subjects in their 40s. The remaining work-related and personal characteristics did not differ significantly according to COVID-19 infection fear level. Burnout and secondary traumatic stress differed significantly among the three groups. Post hoc analysis revealed that the high COVID-19 infection fear group had higher burnout levels and secondary traumatic stress scores than the low and medium fear groups.

Table 1

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the low, intermediate, and high COVID-19 infection fear groups

|

Characteristics |

COVID-19 infection fear |

P value |

|

Low |

Intermediate |

High |

|

No. of participants |

76 |

211 |

84 |

|

|

CIFS score |

6.6 ± 3.3 |

14.4 ± 2.1 |

22.1 ± 2.4 |

< 0.001 |

|

Age group |

|

|

|

0.044 |

|

< 40 yr |

36 (47.4) |

92 (43.6) |

32 (38.1) |

|

In the 40s |

20 (26.3) |

69 (32.7) |

40 (47.6) |

|

≥ 50 yr |

20 (26.3) |

50 (23.7) |

12 (14.3) |

|

Gender (women) |

56 (73.7) |

189 (89.6) |

76 (90.5) |

0.001 |

|

Job title |

|

|

|

0.988 |

|

Physician or nurse |

42 (55.3) |

116 (55.0) |

47 (56.0) |

|

Healthcare assistant |

34 (44.7) |

95 (45.0) |

37 (44.0) |

|

Work institution |

|

|

|

0.585 |

|

Hospital |

35 (46.1) |

94 (44.5) |

33 (39.3) |

|

Residential treatment center |

6 (7.9) |

11 (5.2) |

3 (3.6) |

|

Public health center |

31 (40.8) |

92 (43.6) |

45 (53.6) |

|

Other |

4 (5.3) |

14 (6.6) |

3 (3.6) |

|

Years of healthcare work experience |

|

|

|

0.802 |

|

< 3 |

20 (26.3) |

45 (21.3) |

18 (21.4) |

|

≥ 3 and < 5 |

12 (15.8) |

25 (11.8) |

8 (9.5) |

|

≥ 5 and < 10 |

12 (15.8) |

34 (16.1) |

14 (16.7) |

|

≥ 10 |

32 (42.1) |

107 (50.7) |

44 (52.4) |

|

Years of COVID-19 dedicated team |

|

|

|

0.770 |

|

< 1 |

32 (42.1) |

79 (37.4) |

32 (38.1) |

|

≥ 1 |

44 (57.9) |

132 (62.6) |

52 (61.9) |

|

COVID-19 infection-positive status |

|

|

|

0.602 |

|

Yes |

10 (13.2) |

35 (16.6) |

16 (19.0) |

|

No |

66 (86.8) |

176 (83.4) |

68 (81.0) |

|

COVID-19 isolation experience |

|

|

|

0.771 |

|

Yes |

19 (25.0) |

61 (28.9) |

22 (26.2) |

|

No |

57 (75.0) |

150 (71.1) |

62 (73.8) |

|

K-ProQOL-5 score |

|

|

|

|

|

Compassion satisfaction |

30.2 ± 8.6 |

30.7 ± 6.3 |

29.5 ± 6.4 |

0.353 |

|

Burnout |

26.5 ± 6.1 |

27.2 ± 5.3 |

29.9 ± 5.4 |

< 0.001, a = b < c |

|

Secondary traumatic stress |

22.3 ± 6.9 |

22.8 ± 5.5 |

25.5 ± 5.1 |

< 0.001, a = b < c |

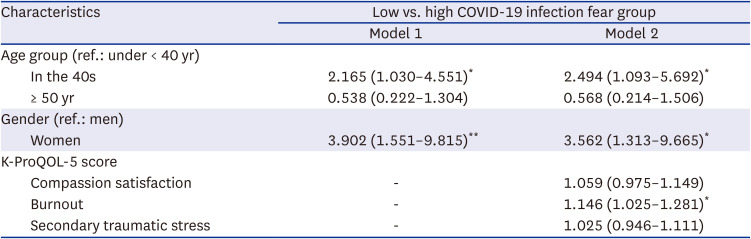

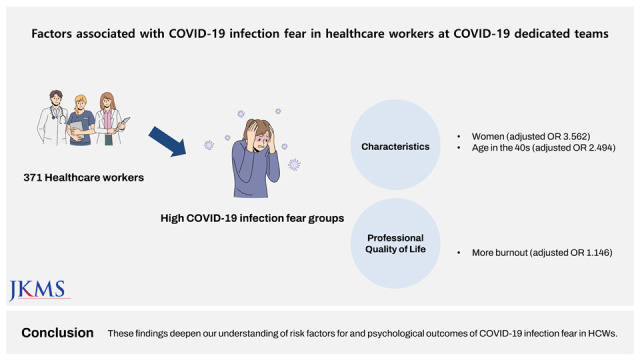

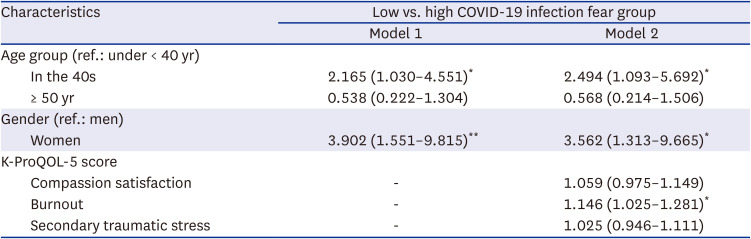

Table 2 summarizes the results of multivariate logistic regression analyses of factors associated with high COVID-19 infection fear, using the low fear group as the reference. Of the demographic variables, being a woman was significantly related to high COVID-19 fear (

P = 0.004, Model 1). In Model 2, which included all variables, being a woman (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 3.562; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.313–9.665;

P = 0.013), age in the 40s (aOR, 2.494; 95% CI, 1.093–5.692;

P = 0.030), and high burnout level (aOR, 1.146; 95% CI, 1.025–1.281;

P = 0.017) were significantly associated with high COVID-19 infection fear.

Table 2

Factors associated with COVID-19 infection fear in healthcare workers in COVID-19 dedicated teams

|

Characteristics |

Low vs. high COVID-19 infection fear group |

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|

Age group (ref.: under < 40 yr) |

|

|

|

In the 40s |

2.165 (1.030–4.551)*

|

2.494 (1.093–5.692)*

|

|

≥ 50 yr |

0.538 (0.222–1.304) |

0.568 (0.214–1.506) |

|

Gender (ref.: men) |

|

|

|

Women |

3.902 (1.551–9.815)**

|

3.562 (1.313–9.665)*

|

|

K-ProQOL-5 score |

|

|

|

Compassion satisfaction |

- |

1.059 (0.975–1.149) |

|

Burnout |

- |

1.146 (1.025–1.281)*

|

|

Secondary traumatic stress |

- |

1.025 (0.946–1.111) |

The results shed light on the characteristics of HCWs with high COVID-19 infection fear, and on the association between professional quality of life and infection fear. These findings could aid the development of effective interventions and prevention strategies. Being a woman was associated with high COVID-19 infection fear, similar to previous studies.

151517 Our results also agreed with the established gender difference in mental health; women tend to experience a higher level of anxiety and fear compared to men.

1819 From a biological and psychological perspective, it is explained that underlying basic factors such as genetic tendencies, characteristic anxiety, and negative emotions create high anxiety in women.

20 These underlying factors can be applied equally to fear of infection. From a socio-cultural point of view, it is argued that women are subject to relatively many obligations and roles, which inevitably increases anxiety.

20 Amid the growing importance of the role of caregivers, many of whom are women, in the COVID-19 situation, there may be many tasks that women need to deal with on a daily basis, and this may have affected COVID-19 infection fear. For example, the caregiving responsibilities of women in their 40s contributed to greater fear and anxiety during the pandemic. Because women can be considered a vulnerable population, they merit special attention during the pandemic.

Our findings indicate higher levels of infection fear were associated with poorer quality of work life of HCWs. Quality of working life can vary according to the nature of work.

21 Different types of work have distinct conditions, characteristics, demands, and impacts on employees. It is helpful for HCWs to show an empathetic attitude toward others’ difficulties and a strong desire to assist in alleviating those difficulties. Empathy allows one to connect with the feelings and experiences of others and can bring about positive emotions, such as pleasure, fulfillment, and gratification when one is able to make a positive difference in the lives of others. These positive emotions are called ‘compassion satisfaction’ which is a factor that improves the professional quality of life of the helper. However, healthcare work can also lead to psychological difficulties. First, the emotional labor associated with sympathizing with people who are suffering can be high, resulting in emotional exhaustion so-called burnout. Second, HCWs may also experience trauma-related symptoms after being indirectly exposed to traumatic incidents. Burnout and secondary traumatic stress are referred to as ‘compassion fatigue,’ leading to a decline in the quality of life for helpers. We found that infection fear was associated with high levels of burnout, similar to previous studies.

222224 Burnout comprises emotional exhaustion, depersonalization or cynicism, and reduced personal accomplishment. Fear is a reaction to perceived or imagined threats characterized by unpleasant emotions and behavioral reactions, such as the fight-or-flight response. A constant state of fear can take a toll on energy levels and the ability to cope with stressors, thus contributing to emotional exhaustion. Persistent fear can make it challenging to find enjoyment in activities, reducing individuals’ motivation and interest in various aspects of their work. Fear can also create a sense of powerlessness and an inability to cope with the fear-provoking situation. This feeling of helplessness can contribute to a sense of inefficacy. Our study also found that infection fear was associated with secondary traumatic stress, similar to previous studies.

2526 Infection fear can involve concerns about safety. HCWs may worry about transmitting the virus to their families or becoming seriously ill themselves, which can contribute to secondary traumatic stress. Our findings show that environments associated with infectious diseases can have a negative impact on professionals’ job satisfaction and well-being.

272729

However, further research is needed to determine the direction of the relationship, whether infection fear leads to decreased quality of work life or if poor quality of work life contributes to increased infection fear. Pre-existing poor work life can increase the fear of infection among individuals. Burnout, characterized by stress, heavy workloads, and overwhelming conditions, can impede their ability to cope with the fear of infection. According to the sensitization hypothesis, prior potentially traumatic event sensitizes people to respond more intensely to subsequent stressors.

30

This study had a few limitations. First, it used a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to infer causality among the variables. A future longitudinal study could thus be useful. Second, the study was limited to a single province and the findings have limited generalizability to HCWs in other regions of Korea. Third, the sample comprises a high proportion of women and a small number of men. This uneven gender distribution could potentially impact the results and limit their generalizability. In further research, a more balanced gender distribution is recommended. Fourth, job title categorical variable subgroups are set too broadly. As there may be differences in gender and age depending on the job title, so it leads to a lack of specificity of information and it could affect the results. Fifth, self-report questionnaires carry a risk of response bias and further study is needed to verify the measurement instrument used to assess the severity of COVID-19 infection fear.

In conclusion, women are a vulnerable group whose mental health may have been particularly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. They need priority interventions to address their mental health needs. Infection fear can have a negative effect on the professional lives of HCWs, leading to reduced work ability. Implementing a plan to lower COVID-19 infection fear among HCWs is crucial for their well-being, job satisfaction, and ability to provide effective care. Interventions to increase compassion satisfaction and lower compassion fatigue, including burnout and secondary traumatic stress, may help mitigate the negative impact of COVID-19 on the well-being of HCWs.

Ethics statement

All protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jeju National University Hospital and the requirement for informed consent was waived (IRB No. JEJUNUH 2022-07-009).

Go to :