1. Baudouin C. COVID-19: the day after. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2020; 43(5):383–385. PMID:

32340758.

2. Wei R, Zhang Y, Gao S, Brown BJ, Hu S, Link BG. Health disparity in the spread of COVID-19: evidence from social distancing, risk of interactions, and access to testing. Health Place. 2023; 82:103031. PMID:

37120950.

3. Kim K, Kim H, Lee J, Cho IK, Ahn MH, Son KY, et al. Functional impairments in the mental health, depression and anxiety related to the viral epidemic, and disruption in healthcare service utilization among cancer patients in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Cancer Res Treat. 2022; 54(3):671–679. PMID:

34583461.

4. Islam N, Sharp SJ, Chowell G, Shabnam S, Kawachi I, Lacey B, et al. Physical distancing interventions and incidence of coronavirus disease 2019: natural experiment in 149 countries. BMJ. 2020; 370:m2743. PMID:

32669358.

5. De Vincentiis L, Carr RA, Mariani MP, Ferrara G. Cancer diagnostic rates during the 2020 ‘lockdown’, due to COVID-19 pandemic, compared with the 2018-2019: an audit study from cellular pathology. J Clin Pathol. 2021; 74(3):187–189. PMID:

32561524.

6. Riera R, Bagattini AM, Pacheco RL, Pachito DV, Roitberg F, Ilbawi A. Delays and disruptions in cancer health care due to COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021; 7(7):311–323. PMID:

33617304.

7. Cohen M, Yagil D, Aviv A, Soffer M, Bar-Sela G. Cancer patients attending treatment during COVID-19: intolerance of uncertainty and psychological distress. J Cancer Surviv. 2022; 16(6):1478–1488. PMID:

35066775.

8. Chung S, Youn S, Choi B. Assessment of cancer-related dysfunctional beliefs about sleep for evaluating sleep disturbance in cancer patients. Sleep Med Rev. 2017; 8(2):98–101.

9. Kim H, Cho IK, Lee D, Kim K, Lee J, Cho E, et al. Effect of cancer-related dysfunctional beliefs about sleep on fear of cancer progression in the coronavirus pandemic. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(36):e272. PMID:

36123961.

10. Lee JB, Jung M, Kim JH, Kim BH, Kim Y, Kim YS, et al. Guidelines for cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53(2):323–329. PMID:

33721486.

11. Pan L, Wang J, Wang X, Ji JS, Ye D, Shen J, et al. Prevention and control of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in public places. Environ Pollut. 2022; 292(Pt B):118273. PMID:

34634404.

12. Wasserman D, van der Gaag R, Wise J. The term “physical distancing” is recommended rather than “social distancing” during the COVID-19 pandemic for reducing feelings of rejection among people with mental health problems. Eur Psychiatry. 2020; 63(1):e52. PMID:

32475365.

13. Newbold SC, Finnoff D, Thunström L, Ashworth M, Shogren JF. Effects of physical distancing to control COVID-19 on public health, the economy, and the environment. Environ Resour Econ. 2020; 76(4):705–729.

14. Mendez-Lopez A, Stuckler D, McKee M, Semenza JC, Lazarus JV. The mental health crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic in older adults and the role of physical distancing interventions and social protection measures in 26 European countries. SSM Popul Health. 2022; 17:101017. PMID:

34977323.

15. Benke C, Autenrieth LK, Asselmann E, Pané-Farré CA. Lockdown, quarantine measures, and social distancing: associations with depression, anxiety and distress at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic among adults from Germany. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 293:113462. PMID:

32987222.

16. Müller F, Röhr S, Reininghaus U, Riedel-Heller SG. Social isolation and loneliness during COVID-19 lockdown: associations with depressive symptoms in the German old-age population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(7):3615. PMID:

33807232.

17. Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, Solo K, Yaacoub S, Schünemann HJ, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020; 395(10242):1973–1987. PMID:

32497510.

18. Yang J, Zhang X, Yu M, Fisher JL, Paskett ED. Associations between cancer history, social distancing behaviors, and loneliness in adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2023; 18(2):e0281713. PMID:

36795688.

19. Gallagher S, Bennett KM, Roper L. Loneliness and depression in patients with cancer during COVID-19. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2021; 39(3):445–451. PMID:

33274697.

20. Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Snowberg K, Abbott M, Borno HT, Chang SM, et al. Loneliness and symptom burden in oncology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancer. 2021; 127(17):3246–3253. PMID:

33905528.

21. Gundavda MK, Gundavda KK. Cancer or COVID-19? A review of recommendations for COVID-19 vaccination in cancer patients. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2021; 22(10):95. PMID:

34515857.

22. Faria de Moura Villela E, López RV, Sato AP, de Oliveira FM, Waldman EA, Van den Bergh R, et al. COVID-19 outbreak in Brazil: adherence to national preventive measures and impact on people’s lives, an online survey. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1):152. PMID:

33461508.

23. Islam JY, Camacho-Rivera M, Vidot DC. Examining COVID-19 preventive behaviors among cancer survivors in the United States: an analysis of the COVID-19 impact survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020; 29(12):2583–2590. PMID:

32978173.

24. Champion VL, Skinner CS. The health belief model. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass;2008. p. 45–65.

25. Cummings KM, Jette AM, Rosenstock IM. Construct validation of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1978; 6(4):394–405. PMID:

299611.

26. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass;2008.

27. Zewdie A, Mose A, Sahle T, Bedewi J, Gashu M, Kebede N, et al. The health belief model’s ability to predict COVID-19 preventive behavior: a systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2022; 10:20503121221113668. PMID:

35898953.

28. Cislaghi B, Heise L. Theory and practice of social norms interventions: eight common pitfalls. Global Health. 2018; 14(1):83. PMID:

30119638.

29. Dempsey RC, McAlaney J, Bewick BM. A Critical appraisal of the social norms approach as an interventional strategy for health-related behavior and attitude change. Front Psychol. 2018; 9:2180. PMID:

30459694.

30. Schultz PW, Nolan JM, Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ, Griskevicius V. The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychol Sci. 2007; 18(5):429–434. PMID:

17576283.

31. Liu S, Zhu J, Liu Y, Wilbanks D, Jackson JC, Mu Y. Perception of strong social norms during the COVID-19 pandemic is linked to positive psychological outcomes. BMC Public Health. 2022; 22(1):1403. PMID:

35869459.

32. Latkin CA, Dayton L, Kaufman MR, Schneider KE, Strickland JC, Konstantopoulos A. Social norms and prevention behaviors in the United States early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Health Med. 2022; 27(1):162–177. PMID:

34794362.

33. Gouin JP, MacNeil S, Switzer A, Carrese-Chacra E, Durif F, Knäuper B. Socio-demographic, social, cognitive, and emotional correlates of adherence to physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Can J Public Health. 2021; 112(1):17–28. PMID:

33464556.

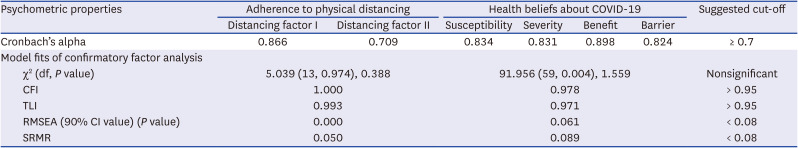

34. Hong Y, An H, Cho E, Ahmed O, Ahn MH, Yoo S, et al. Psychometric properties of the Korean version of questionnaires on adherence to physical distancing and health beliefs about COVID-19 in the general population. Front Psychiatry. 2023; 14:1132169. PMID:

37484663.

35. Chung S, Lee T, Hong Y, Ahmed O, Silva WA, Gouin JP. Viral anxiety mediates the influence of intolerance of uncertainty on adherence to physical distancing among healthcare workers in COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 13:839656. PMID:

35733798.

36. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004; 6(3):e34. PMID:

15471760.

37. Chung S, Ahn MH, Lee S, Kang S, Suh S, Shin YW. The Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-6 Items (SAVE-6) scale: a new instrument for assessing the anxiety response of general population to the viral epidemic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021; 12:669606. PMID:

34149565.

38. Chung S, Kim HJ, Ahn MH, Yeo S, Lee J, Kim K, et al. Development of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) scale for assessing work-related stress and anxiety in healthcare workers in response to viral epidemics. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(47):e319. PMID:

34873885.

39. Löwe B, Kroenke K, Gräfe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). J Psychosom Res. 2005; 58(2):163–171. PMID:

15820844.

40. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(9):606–613. PMID:

11556941.

41. Pfizer. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) screeners. Updated 2010. Accessed January 10, 2022.

www.phqscreeners.com

.

42. Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;2001.

43. Kamble S, Joshi A, Kamble R, Kumari S. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on psychological status: an elaborate review. Cureus. 2022; 14(10):e29820. PMID:

36337829.

44. Leonard BE, Song C. Stress and the immune system in the etiology of anxiety and depression. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996; 54(1):299–303. PMID:

8728571.

45. Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990; 58(6):1015–1026.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download