1. Gupta S, Sahoo S. Pandemic and mental health of the front-line healthcare workers: a review and implications in the Indian context amidst COVID-19. Gen Psychiatr. 2020; 33(5):e100284. PMID:

34192235.

2. Xu H, Stjernswärd S, Glasdam S. Psychosocial experiences of frontline nurses working in hospital-based settings during the COVID-19 pandemic - a qualitative systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2021; 3:100037. PMID:

34308373.

3. Murat M, Köse S, Savaşer S. Determination of stress, depression and burnout levels of front-line nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021; 30(2):533–543. PMID:

33222350.

4. Hernandez JM, Munyan K, Kennedy E, Kennedy P, Shakoor K, Wisser J. Traumatic stress among frontline American nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study. Traumatology. 2021; 27(4):413–418.

5. Rector NA, Kamkar K, Cassin SE, Ayearst LE, Laposa JM. Assessing excessive reassurance seeking in the anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2011; 25(7):911–917. PMID:

21641764.

6. Warwick HM. A cognitive-behavioural approach to hypochondriasis and health anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 1989; 33(6):705–711. PMID:

2621674.

7. Parrish CL, Radomsky AS. Why do people seek reassurance and check repeatedly? An investigation of factors involved in compulsive behavior in OCD and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2010; 24(2):211–222. PMID:

19939622.

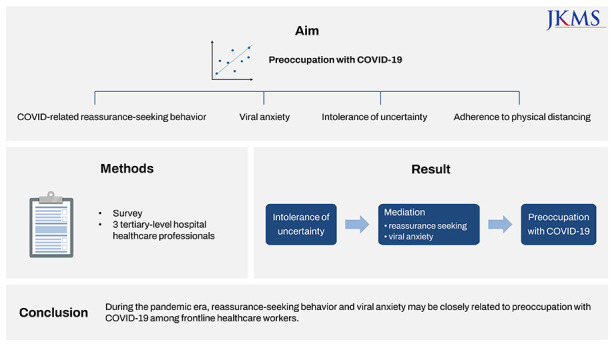

8. Cho E, Lee D, Cho IK, Lee J, Ahn J, Bang YR. Insomnia mediate the influence of reassurance-seeking behavior and viral anxiety on preoccupation with COVID-19 among the general population. Sleep Med Rev. 2022; 13(2):68–74.

9. Kim HS, Ahn J, Lee J, Hong Y, Kim C, Park J, et al. The mediating effect of reassurance-seeking behavior on the influence of viral anxiety and depression on COVID-19 obsession among medical students. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 13:899266. PMID:

35770057.

10. Lee J, Cho IK, Lee D, Kim K, Ahn MH, Chung S. Mediating effects of reassurance-seeking behavior or obsession with COVID-19 on the association between intolerance of uncertainty and viral anxiety among healthcare workers in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(21):e157. PMID:

35638193.

11. Jo Y, Shrestha S, Radnaabaatar M, Park H, Jung J. Optimal social distancing policy for COVID-19 control in Korea: a model-based analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(23):e189. PMID:

35698839.

12. Chen L, Wang D, Xia Y, Zhou R. The association between quarantine duration and psychological outcomes, social distancing, and vaccination intention during the second outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Int J Public Health. 2022; 67:1604096. PMID:

35321049.

13. Chung S, Lee T, Hong Y, Ahmed O, Silva WA, Gouin JP. Viral anxiety mediates the influence of intolerance of uncertainty on adherence to physical distancing among healthcare workers in COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 13:839656. PMID:

35733798.

14. Di Trani M, Mariani R, Ferri R, De Berardinis D, Frigo MG. From resilience to burnout in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 emergency: the role of the ability to tolerate uncertainty. Front Psychol. 2021; 12:646435. PMID:

33935905.

15. Hacimusalar Y, Kahve AC, Yasar AB, Aydin MS. Anxiety and hopelessness levels in COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative study of healthcare professionals and other community sample in Turkey. J Psychiatr Res. 2020; 129:181–188. PMID:

32758711.

16. Chan-Yeung M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and healthcare workers. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2004; 10(4):421–427. PMID:

15702757.

17. Lee SA. How much “Thinking” about COVID-19 is clinically dysfunctional? Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87:97–98. PMID:

32353520.

18. Choi E, Lee J, Lee SA. Validation of the Korean version of the obsession with COVID-19 scale and the coronavirus anxiety scale. Death Stud. 2022; 46(3):608–614. PMID:

34030606.

19. Lee SA, Jobe MC, Mathis AA, Gibbons JA. Incremental validity of coronaphobia: coronavirus anxiety explains depression, generalized anxiety, and death anxiety. J Anxiety Disord. 2020; 74:102268. PMID:

32650221.

20. Kim C, Ahmed O, Park CH, Chung S. Validation of the Korean version of the coronavirus reassurance-seeking behaviors scale during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Investig. 2022; 19(6):411–417.

21. Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022; 20(3):1537–1545. PMID:

32226353.

22. Hwang KS, Choi HJ, Yang CM, Hong J, Lee HJ, Park MC, et al. The Korean version of Fear of COVID-19 Scale: psychometric validation in the Korean population. Psychiatry Investig. 2021; 18(4):332–339.

23. Freeston MH, Rhéaume J, Letarte H, Dugas MJ, Ladouceur R. Why do people worry? Pers Individ Dif. 1994; 17(6):791–802.

24. Kim S. The relationship of fear of negative and positive evaluation, intolerance of uncertainty, and social anxiety [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Seoul, Korea: Ewha Womans University;2010. p. 26.

25. Gouin JP, MacNeil S, Switzer A, Carrese-Chacra E, Durif F, Knäuper B. Socio-demographic, social, cognitive, and emotional correlates of adherence to physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Can J Public Health. 2021; 112(1):17–28. PMID:

33464556.

26. Dugas MJ, Gosselin P, Ladouceur R. Intolerance of uncertainty and worry: Investigating specificity in a nonclinical sample. Cognit Ther Res. 2001; 25(5):551–558.

27. Lee J, Cho IK, Lee D, Kim K, Ahn MH, Chung S. Mediating effects of reassurance-seeking behavior or obsession with COVID-19 on the association between intolerance of uncertainty and viral anxiety among healthcare workers in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(21):e157. PMID:

35638193.

28. Carleton RN, Mulvogue MK, Thibodeau MA, McCabe RE, Antony MM, Asmundson GJ. Increasingly certain about uncertainty: Intolerance of uncertainty across anxiety and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2012; 26(3):468–479. PMID:

22366534.

29. Millroth P, Frey R. Fear and anxiety in the face of COVID-19: Negative dispositions towards risk and uncertainty as vulnerability factors. J Anxiety Disord. 2021; 83:102454. PMID:

34298237.

30. Lee MH, Kim MY, Go YJ, Kim DR, Lim HN, Lee KH, et al. Factors influencing in the infection control performance of COVID-19 in nurses. J Digit Converg. 2021; 19(3):253–261.

31. Beck E, Daniels J. Intolerance of uncertainty, fear of contamination and perceived social support as predictors of psychological distress in NHS healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Health Med. 2023; 28(2):447–459. PMID:

35792750.

32. Kartal N, Arıkan G, Seyhan F, Aydan S. Mediator roles of resilience and intolerance of uncertainty in the effect of healthcare professionals’ coronavirus stigma on stress. Int J Healthc Manag. 2023; 16(1):120–127.

33. Bakioğlu F, Korkmaz O, Ercan H. Fear of COVID-19 and positivity: mediating role of intolerance of uncertainty, depression, anxiety, and stress. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2021; 19(6):2369–2382. PMID:

32837421.

34. Apisarnthanarak A, Apisarnthanarak P, Siripraparat C, Saengaram P, Leeprechanon N, Weber DJ. Impact of anxiety and fear for COVID-19 toward infection control practices among Thai healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020; 41(9):1093–1094. PMID:

32507115.

35. Cho IK, Ahmed O, Lee D, Cho E, Chung S, Günlü A. Intolerance of uncertainty mediates the influence of viral anxiety on social distancing phobia among the general Korean population during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Psychiatry Investig. 2022; 19(9):712–721.

36. Kim JH, Seo MS, Chung S. The influence of physical distancing, sense of belonging, and resilience of nursing students on their viral anxiety during the COVID-19 era. Psychiatry Investig. 2022; 19(5):386–393.

37. Yusefi AR, Daneshi S, Davarani ER, Nikmanesh P, Mehralian G, Bastani P. Resilience level and its relationship with hypochondriasis in nurses working in COVID-19 reference hospitals. BMC Nurs. 2021; 20(1):219. PMID:

34727947.

38. Jihn CH, Kim B, Kim KS. Predictors of burnout in hospital health workers during the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11720. PMID:

34770231.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download