INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a significant global health concern. HCV infection becomes chronic in many cases. It is known to be a significant cause of chronic liver disease because there is no effective vaccination yet. Chronic HCV infection has contributed to increasing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) related mortality in many countries and has also resulted in an enormous economic burden and lost productivity.

12 Chronic liver disease in HCV-infected individuals often remains asymptomatic for several decades until the liver disease is advanced.

3 Moreover, most individuals with chronic hepatitis C are unaware of their serostatus and they are likely to transmit the infection to others.

The number of North Korean defectors is increasing in South Korea. According to the Ministry of Unification, it is estimated that 9,042 men and 24,256 women moved to South Korea until March 31, 2020.

4 Similar to other refugee populations, North Korean defectors are less healthy than South Koreans due to many physical and mental health problems that may have been acquired from exposure to traumatic events and infectious diseases while in North Korea or during their defection.

5 Although various free health checkup programs are offered to North Korean defectors by academic societies and hospitals in South Korea, most hepatitis B and C cases are still undiagnosed. They are not known or treated until they progress to chronic liver diseases. Furthermore, the most serious problem is that people with chronic hepatitis can infect others without their knowledge. Specifically, hepatitis C may be more problematic as it is not included in the National Health Screening Program in South Korea.

The prevalence rate of chronic HCV is approximately 3% worldwide and 1.5% in South Korea.

6 However, the prevalence rate of HCV and characteristics of the disease in North Korea have not been openly and widely reported. Chronic HCV patients often remain asymptomatic for 30 years or more until the liver disease progresses. It is well known that early diagnosis is critical as treatment usually leads to viral eradication, prevents liver disease progression, and decreases liver-related mortality. Moreover, the recent development of safer, more tolerable, and highly effective oral direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) provide a cure for chronic HCV infections. Therefore, early detection is essential as treatments usually achieve viral eradication, which prevents HCV transmission, progression of liver disease and decreases morbidity and all-cause mortality. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the prevalence rate of HCV infection and identify the demographic and sociological characteristics of North Korean defectors living in South Korea. This study also aimed to investigate the changes in awareness of HCV infection by participating in this study.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This prospective study was conducted between September 2020 and June 2021. Participants were recruited with the cooperation of the Hana Center, a non-profit public organization established by the Ministry of Unification. The inclusion criteria comprised adults aged 19 years and older. The exclusion criteria included those treated for HCV infection or currently being treated. Participants were screened using the anti-hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV Ab) test and a positive result was confirmed by the HCV RNA test on the second visit. Upon initial enrollment, routine checkups, including hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg), and anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface Ab were also conducted. A questionnaire survey was conducted to evaluate the participants’ awareness of HCV infection using yes/or no questions.

Data collection and questionnaire survey

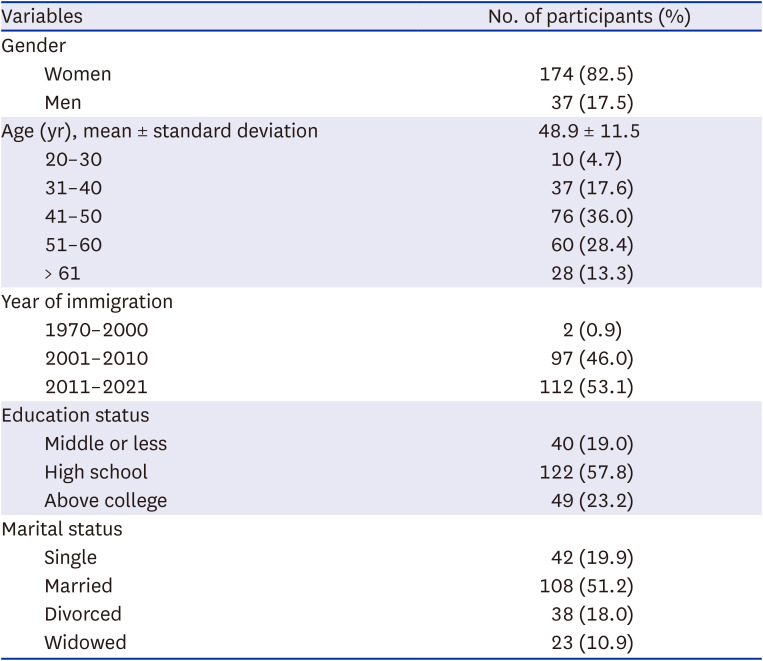

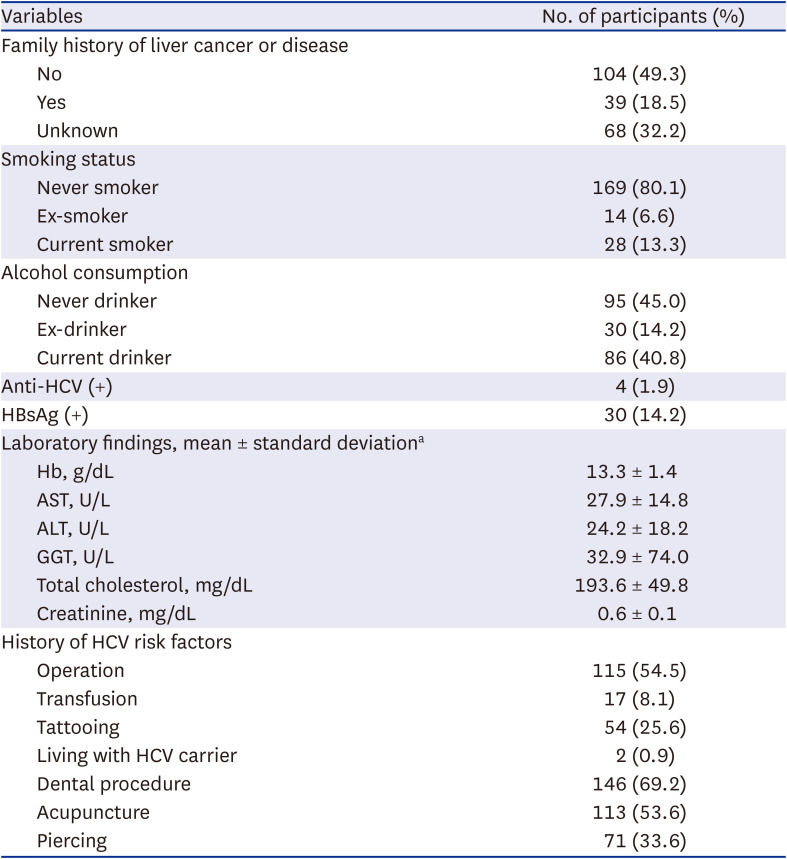

The data collected included laboratory and chest X-ray findings. Laboratory results included anti-HCV Ab, the HBsAg, and anti-HBV surface Ab, and hemoglobin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransaminase (ALT), gamma glutamyl transferase, fasting glucose, total cholesterol and creatinine. We collected the data on sociodemographic status (age, sex, marital status, education level), health behaviors (smoking and alcohol consumption), and family history of hepatitis-related liver disease. We also assessed their exposure to possible risk factors for HCV infections, such as intravenous drug use (IVDU), surgery, blood transfusion, history of tattooing, living with HCV carriers, hemodialysis, the number of sexual partners, dental procedures, acupuncture, and piercing. Awareness of HCV infection was evaluated using a questionnaire survey. Several questions were asked about whether the participants were aware of the HCV infection before the study participation and changes in participants’ awareness of the need to treat HCV infection after study participation.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and non-continuous variables are expressed as frequency (percent).

Ethics statement

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained at each site before enrollment (IRB No. Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital 04-2019-017, Pusan National University Hospital 2002-012-088). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

DISCUSSION

HCV can cause acute and chronic hepatitis and chronic HCV infection can result in liver cirrhosis and HCC.

7 As HCV infection is a major public health problem worldwide, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the elimination of hepatitis C by 2030 and urged global efforts. Refugees and migrants are reported to have a risk of contracting HCV infection because of a lack of health care and information about the prevention and methods of transmission.

8 Most people with HCV are unaware of their infection and remain infectious to others. The risk of HCC development in patients with chronic hepatitis C before cirrhosis is negligible. However, the risk increases rapidly after progression to cirrhosis, and even if the virus is cured with antiviral treatment, it does not disappear completely.

9 However, recently, the virus cure rate has recently increased to 98–99% when using DAAs for 8 to 12 weeks. Therefore, HCV related HCC and liver failure can be almost entirely prevented by actively identifying and treating as many chronic hepatitis C patients as early as possible before the disease progresses through the national health checkups.

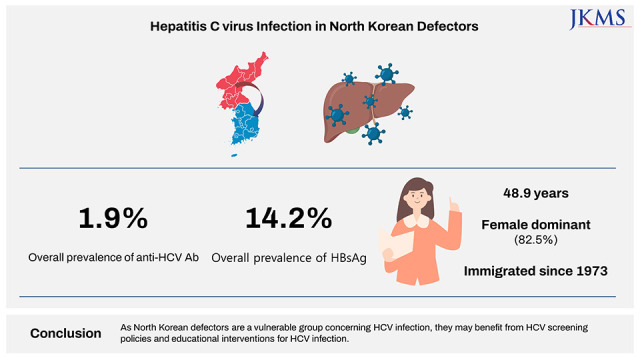

This study revealed that the seroprevalence of anti-HCV antibodies in North Korean defectors was 1.9%. The anti-HCV prevalence is often referred to as the HCV infection prevalence even though the anti-HCV prevalence does not completely coincide with the prevalence of HCV infection. This is because only a small percentage of all patients were completely cured of the virus with treatment, and the anti-HCV Ab test is the most widely used screening test. HCV infection has a rare spontaneous recovery, and DAAs was introduced in 2011. Epidemiological data and prevalence estimates vary widely within and between countries. According to the WHO classification, anti-HCV seroprevalence can be graded as high (> 3.5%), moderate (1.5–3.5%), and low (< 1.5%).

10 The current study found a moderate prevalence of anti-HCV, 1.9%. A previous study conducted among refugees in the United States revealed an anti-HCV seroprevalence of 1.6%.

11 However, this prevalence varied based on the countries of origin. In European countries, the prevalence of HCV infection among immigrant populations from different countries was higher than general populations ranging from 0.1% to 5.9%.

12 The prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies exhibited a wide range, with some cases reaching as high as 19.2%.

13 A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that the migrant population living in low HCV prevalence countries was 1.9%.

14 Although the prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies in this study was similar to that found among immigrants and refugees in different countries, it is important to note that the distribution of age and gender can vary in studies examining the prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies among refugees, depending on the specific study and population being investigated. Additionally, it is crucial to consider that access to healthcare and screening for HCV may differ among immigrant and refugee populations, potentially affecting the reported prevalence rates.

This finding revealed a significant prevalence compared to South Korea’s anti-HCV prevalence of 0.6–1.3%.

15 Several studies have reported the prevalence of infectious diseases among North Korean defectors.

1617 Viral hepatitis appeared among the most commonly identified diseases in all surveys, with prevalence rates ranging from 8.2% to 20.4%.

16 Although there were many participants in each study, there were some limitations. Because the surveys relied only on interviews, the results did not adhere to the objective diagnostic criteria and the survey methods differed (e.g., targeting healthy persons or recruiting only symptomatic individuals). Moreover, the results of viral hepatitis prevalence included both HBV and HCV infections and did not entirely reflect the prevalence of HCV infection. There is a retrospective study to investigate the clinical characteristics of North Korean defectors who visited a single tertiary hospital in South Korea.

17 Ninety-one patients underwent an anti-HCV Ab test, and 20 patients (22.0%) were positive. Among these 20 patients, 17 were tested for HCV RNA, and 16 were positive, showing a prevalence rate of 17.6% for chronic hepatitis C. Although the prevalence of HCV infection is relatively high, the selection bias seems to have occurred because the North Korean defectors who enrolled in the above study frequently visited the tertiary hospital for treatment after receiving a diagnosis. The most recent global estimates report that the global prevalence of HCV infection (prevalence of HCV RNA) is estimated to be 1.0%. The prevalence was significantly higher in certain African countries with the highest prevalence at 7.0% in Gabon.

18 In this study, none of the participants with positive anti-HCV antibodies was diagnosed with viremic HCV.

The prevalence of hepatitis B in this study was 14.2%, classified as a high prevalence. HBsAg prevalence was classified as low (< 2%), intermediate (2–8%), and high (> 8%) prevalence according to the WHO.

19 The current finding was much higher than that reports in other refugees. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that the overall seroprevalence of chronic hepatitis B for immigrants and refugees from various countries was 7.2%.

20 Our result showed a similar prevalence of hepatitis B in previous reports done in South Korea. According to a report from Hanawon, a Ministry of Unification halfway-house, among 6,087 North Korean defectors who underwent a health checkup between 2004 and 2007, 669 (10.9%) were infected with hepatitis B, which was more than twice the positivity rate for HBsAg among Koreans during the same period of 4%.

21 As a result of a free health checkup conducted by the Korean Association for the Study of the Liver and Korean Liver Foundation on a total of 178 North Korean defectors in 2014, the HBsAg positivity rate was 16%, which was higher than the previous results. According to a retrospective study investigating the clinical characteristics of North Korean defectors visiting a single tertiary hospital in South Korea, 88 patients underwent the HBsAg test, and 17 (19.3%) were positive.

17 The probable reasons for this high prevalence may be due to the high natural prevalence in the region, and the lack of vaccinations and antiviral treatment.

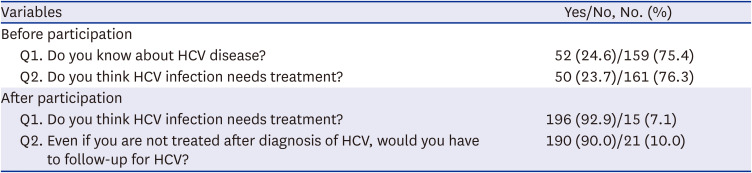

The current study has also assessed the participant’s awareness of HCV infection. A huge lack of awareness regarding HCV infection has been observed among North Korean defectors. More than 70% lacked knowledge and the appropriate attitude toward HCV infection. This lack of knowledge was similar to the results of the study among refugees, although the participants in our study had a relatively higher educational level.

22 Interestingly, we can observe changes in participants’ awareness of HCV infection by participating in the study. This is thought to be due to the information about HCV that is obtained during the study.

This study had some limitations. First, although the current study included a relatively large number of North Korean defectors prospectively, this does not represent the entire North Korean defectors living in South Korea. Second, because our study participants were more likely to pay more attention to their health, we expect that anti-HCV prevalence and HCV infection of the entire North Korean defector population would be higher than the prevalence rate reported here. Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively investigate the prevalence of HCV infection among North Korean defectors living in South Korea. In addition, our study showed the effects and importance of education on viral hepatitis. We demonstrated that HCV education could increase people’s knowledge of HCV disease and willingness to accept HCV treatment.

The findings of this study suggest that North Korean defectors are a vulnerable group concerning HCV infection, and their awareness of HCV infection is limited. Considering that liver cirrhosis is one of the highest ranked diseases in the disease burden of North Korean defectors in South Korea,

23 our study is meaningful as it can provide the basis for the need for HCV test to be implemented in South Korea’s national health screening program.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download