Abstract

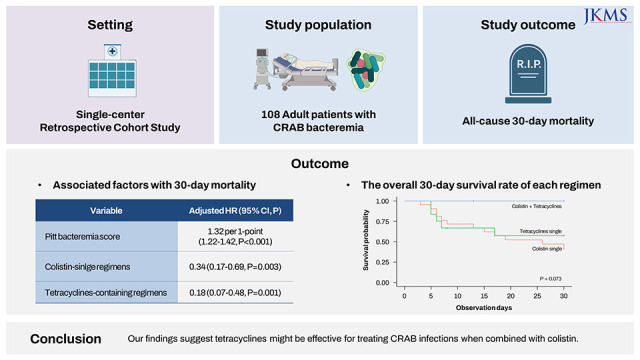

This study evaluated the clinical outcome of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) bacteremia and the clinical effectiveness of tetracyclines-based therapy. In a retrospective cohort study over 5 years period, 108 patients were included in the study. The overall 30-day mortality rate was 71.4%. Pitt’s bacteremia score (PBS) (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.32; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.22–1.42 per 1-point), colistin-single regimens (aHR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.17–0.69), and tetracyclines single/tetracyclines-colistin combination regimens (aHR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.07–0.48) were independently associated with 30-day mortality. Among patients with a PBS < 6, only tetracycline-containing regimens were associated with decreased mortality. Among patients receiving appropriate definite antimicrobials, the tetracyclines-colistin combination (7 of 7, 100%) tended to a higher 30-day survival rate compared to a tetracycline (7 of 12, 57.1%) or colistin single regimen (10 of 22, 41.6%, P = 0.073). Our findings suggest tetracyclines might be effective for treating CRAB infections when combined with colistin.

Graphical Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii is one of the most challenging organisms encountered in hospital-acquired infections.12 National surveillance data from the Republic of Korea show that more than 90% of clinical A. baumannii isolates have carbapenem resistance.3 Usually, carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) is only susceptible to polymyxin and certain tetracycline-class agents.4

To improve the clinical outcome of CRAB infection, combination antibiotic therapy has been investigated.1456 The combination of colistin and tetracyclines has shown promising in vitro and in vivo activity against CRAB, but few clinical studies have evaluated its effectiveness.4678 In this retrospective study, we evaluated the clinical outcome of patients with CRAB bacteremia and the effectiveness of tetracyclines-based therapy.

This study was conducted at Samsung Changwon Hospital, a 750-bed tertiary care academic hospital. From January 2016 through December 2020, adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) with documented CRAB bacteremia were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with polymicrobial bacteremia and those who were referred to other medical centers within 5 days after bacteremia onset were excluded. Data on antimicrobial use and patient characteristics were collected from electronic medical records. Appropriate definitive antibiotic use was defined when antibiotics susceptible to CRAB were administered for at least two days within seven days after bacteremia onset. All administered minocycline was in oral formulation (200 mg loading once, and then 100 mg twice daily).

The study outcome was the overall 30-day mortality. Treatment regimens were categorized into four groups: 1) those who never received appropriate antibiotics, 2) those who received colistin-single regimens (excluding tetracyclines), 3) those who received tetracycline-containing regimens (with or without colistin), and 4) those who received carbapenem combination regimens. Due to the high mortality rate associated with CRAB infection, as reported in prior studies,9 we conducted additional subgroup analyses. The subgroup analysis was designed to include low-risk patients with CRAB bacteremia based on risk factors identified in the study population.

Blood was drawn for two sets of blood culture bottles and incubated in the A Bactec-9240 system (Becton, Dickinson, and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) or BacT/Alert 3D system (bioMérieux Inc., Marcy l’Etoile, France). Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed with a Vitek II automated system (bioMérieux Inc.) according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute M100 S16:2018 guidelines.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R software (version 4.2.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Cox regression analysis was conducted for evaluating the association between variables and overall 30 days mortality. Variables with stastical significance in the univariate analysis were included in the forward stepwise and non-stepwise multivariable model. All P values were two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

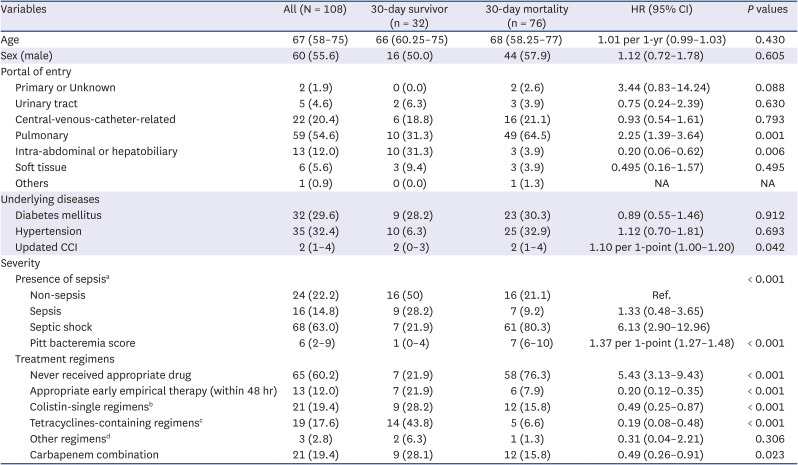

A total of 108 eligible patients with CRAB bacteremia were included (Supplementary Fig. 1). The overall seven- and 30-day mortality rates were 60.2% (65/108) and 70.9% (76/108), respectively. Only 39.8% (43/108) of patients could receive appropriate definite antimicrobials. Specific treatment regimens and antimicrobial susceptibility of CARB isolates were presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively. In the univariable analysis for overall 30-day mortality, pulmonary infection, intra-abdominal and hepatobiliary infection, Updated Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), disease severity, Pitt’s bacteremia score (PBS), and treatment regimen were associated with 30-day mortality (Table 1). Especially, the mortality of patients with a PBS ≥ 6 was 96.7% (58/60).

In the multivariable model, a higher PBS (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.32 per 1 point; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.22–1.42; P < 0.001) was associated with higher overall 30-day mortality. Colistin-single regimens (aHR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.17–0.69; P = 0.003) and tetracycline-containing regimens (aHR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.07–0.48; P = 0.001 in forward stepwise model) were associated with lower mortality (Supplementary Table 3).

Because of the extremely high mortality of patients with high PBS, the subgroup analysis was conducted among patients with a PBS < 6. In the multivariable analysis, only tetracyclines-containing regimens were associated with decreased mortality (aHR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.05–0.99; P = 0.048 in forward stepwise model) (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5).

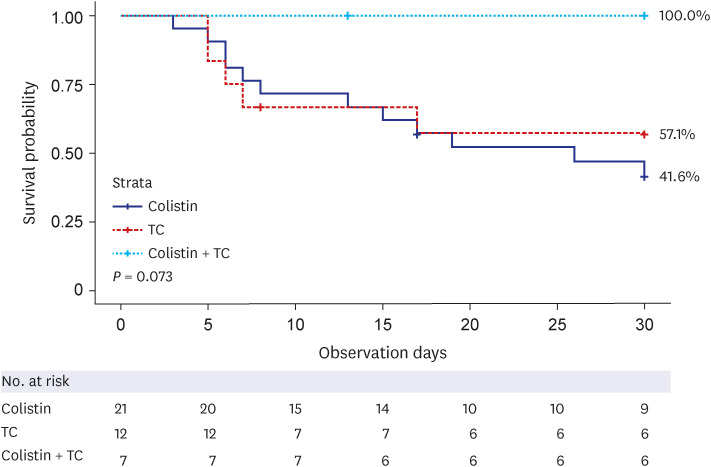

When patients who received appropriate definitive antimicrobial agents were compared by antimicrobial regimens, the survival rate of patients treated with the tetracyclines-colistin combination (7 of 7, 100%) tended to a higher 30-day survival rate compared to a tetracycline (7 of 12, 57.1%) or colistin single regimen (10 of 22, 41.6%, P = 0.073) (Fig. 1).

Our study demonstrated extremely high early mortality of patients with CRAB bacteremia. We found that tetracycline-containing regimens were independently associated with decreased 30-day mortality, particularly among patients with a low Pitt's bactermia score. Although the difference did not reach statistical significance, the tetracycline-colistin combination tended to have a higher 30-day survival rate than either antibiotic used alone. Our findings suggest that tetracyclines may be a valuable option for treating CRAB infections, particularly when combined with other antibiotics.

To overcome the resistance to CRAB, alternative or combination therapy has been studied.5678910 Colistin-carbapenem combination therapy was frequently prescribed for patients with CRAB infection;5 however, an open-labeled randomized controlled trial did not show the superiority of colistin-carbapenem combination treatment compared to colistin monotherapy for carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli infection (including in 77% of infections caused by A. baunannii).9

Occasionally, clinical CRAB isolates retain susceptibility to tetracyclines.111 National surveillance data from South Korea in 2017 indicated that < 10% of A. baumannii isolates from clinical specimens were resistant to tigecycline or minocycline.3 Although tigecycline has been widely used for the infection of drug-resistant pathogens, including CRAB,12 there are concerns about its monotherapy. One concern is potential adverse clinical outcomes determined from a meta-analysis, and the other is low serum concentration.1 Meanwhile, minocycline has been highlighted as a promising drug. The efflux pumps (TetA, except for the TetB) distributed in A. baumannii can effectively transport tetracycline or doxycycline out of the cells, but not minocycline.13 However, limited data have been reported on the efficacy of minocycline from a few observational studies with CRAB infection.113

Because of the limitations of using tigecycline and minocycline as monotherapies, these agents have been investigated as a component of combination therapy. Tigecycline and minocycline have been shown to have synergistic effects for A. buamannii when combined with colistin in vitro1415; however, a retrospective study of patients with CRAB bacteremia did not show a difference in overall 30-day mortality between colistin–tigecycline combination and colistin monotherapy.7 Clinical data for minocycline combination therapy are also scarce. Seok et al.6 reported that minocycline-containing regimens were associated with improved microbiological eradication (but not survival rate) for CRAB infection. In our study, carbapenem combination therapy did not correlate with the clinical outcomes of patients with CRAB bacteremia. However, tetracyclines-containing regimens, especially tetracyclines-colistin combination therapy, were associated with lower 30-day mortality. The mechanism of tetracyclines-colistin synergism was presumed to be the increased intracellular concentration of second agents by colistin effects, increasing membrane permeability.8

There are some limitations of this study. First, the number of patients receiving appropriate antibiotics was relatively small. However, our study analyses consistently showed an association between tetracyclines use and improved clinical outcomes. Our study could be a pilot study supporting the use of tetracyclines for CRAB infection. Second, the outcomes of CRAB bacteremia could be heterogeneous according to the portal of entry. For example, among 17 patients with CRAB bacteremic pneumonia in this study, only two patients (11.8%) received tetracycline-containing regimens, and one patient treated with tigecycline single therapy was deceased. Therefore, we could not conclude the effectiveness of tetracyclines-based therapy in pneumonia from our study. Further studies on tetracyclines are needed to evaluate their efficacy for CRAB according to infection focus.

In conclusion, our study showed the clinical usefulness of tetracyclines for CRAB infection, especially for low-risk patients, when used in combination with colistin.

The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Samsung Changwon Hospital (IRB number: SCMC 2022-01-006-002). The need for informed consent was waived by the board because this was an observational retrospective study, and all patient data were analyzed anonymously.

Notes

Funding: This work was supported by the Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine Samsung Changwon Hospital (2022).

References

1. Piperaki ET, Tzouvelekis LS, Miriagou V, Daikos GL. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: in pursuit of an effective treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019; 25(8):951–957. PMID: 30914347.

2. Kim D, Lee H, Choi JS, Croney CM, Park KS, Park HJ, et al. The changes in epidemiology of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia in a pediatric intensive care unit for 17 years. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(24):e196. PMID: 35726147.

3. Lee H, Yoon EJ, Kim D, Jeong SH, Won EJ, Shin JH, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of major clinical pathogens in South Korea, May 2016 to April 2017: first one-year report from Kor-GLASS. Euro Surveill. 2018; 23(42):1800047. PMID: 30352640.

4. Tamma PD, Aitken SL, Bonomo RA, Mathers AJ, van Duin D, Clancy CJ. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidance on the treatment of Ampc β-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2022; 74(12):2089–2114. PMID: 34864936.

5. Shi H, Lee JS, Park SY, Ko Y, Eom JS. Colistin plus carbapenem versus colistin monotherapy in the treatment of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia. Infect Drug Resist. 2019; 12:3925–3934. PMID: 31920347.

6. Seok H, Choi WS, Lee S, Moon C, Park DW, Song JY, et al. What is the optimal antibiotic treatment strategy for carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB)? A multicentre study in Korea. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2021; 24:429–439. PMID: 33571708.

7. Amat T, Gutiérrez-Pizarraya A, Machuca I, Gracia-Ahufinger I, Pérez-Nadales E, Torre-Giménez Á, et al. The combined use of tigecycline with high-dose colistin might not be associated with higher survival in critically ill patients with bacteraemia due to carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018; 24(6):630–634. PMID: 28970161.

8. Yang YS, Lee Y, Tseng KC, Huang WC, Chuang MF, Kuo SC, et al. In vivo and in vitro efficacy of minocycline-based combination therapy for minocycline-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016; 60(7):4047–4054. PMID: 27114274.

9. Paul M, Daikos GL, Durante-Mangoni E, Yahav D, Carmeli Y, Benattar YD, et al. Colistin alone versus colistin plus meropenem for treatment of severe infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018; 18(4):391–400. PMID: 29456043.

10. Saelim W, Changpradub D, Thunyaharn S, Juntanawiwat P, Nulsopapon P, Santimaleeworagun W. Colistin plus sulbactam or fosfomycin against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: improved efficacy or decreased risk of nephrotoxicity? Infect Chemother. 2021; 53(1):128–140. PMID: 34409786.

11. Kim YA, Park YS. Epidemiology and treatment of antimicrobialresistant gram-negative bacteria in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2018; 33(2):247–255. PMID: 29506343.

12. Shin JA, Chang YS, Kim HJ, Kim SK, Chang J, Ahn CM, et al. Clinical outcomes of tigecycline in the treatment of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Yonsei Med J. 2012; 53(5):974–984. PMID: 22869481.

13. Lashinsky JN, Henig O, Pogue JM, Kaye KS. Minocycline for the treatment of multidrug and extensively drug-resistant A. baumannii: a review. Infect Dis Ther. 2017; 6(2):199–211. PMID: 28357705.

14. Mutlu Yilmaz E, Sunbul M, Aksoy A, Yilmaz H, Guney AK, Guvenc T. Efficacy of tigecycline/colistin combination in a pneumonia model caused by extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012; 40(4):332–336. PMID: 22831842.

15. Sung H, Choi SJ, Yoo S, Kim MN. In vitro antimicrobial synergy against imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Korean J Lab Med. 2007; 27(2):111–117. PMID: 18094561.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Suppelmentary Table 3

Associated factors with overall 30-day mortality in multivariable analysis

Supplementary Table 4

Associated factors with an overall 30-day mortality of patients with Pitt bacteremia score < 6

Suppelmentary Table 5

Associated factors with overall 30-day mortality of patients with Pitt bacteremia score < 6 in multivariable analysis

Table 1

Associated factors with overall 30-day mortality

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

CCI = Charlson comorbidity index, HR = adjusted hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval.

aNon-sepsis, sepsis, and septic shock were classified by the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3); bColistin-containing regimen (excluding tetracyclines); cTetracycline-containing regimens (with or without colistin, ten patients received tigecycline and nine received minocycline); dTwo patients received quinolones, and one patient received gentamicin.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download