1. Kogame N, Ono M, Kawashima H, et al. The impact of coronary physiology on contemporary clinical decision making. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020; 13:1617–1638. PMID:

32703589.

2. Hwang D, Yang S, Zhang J, Koo BK. Physiologic assessment after coronary stent implantation. Korean Circ J. 2021; 51:189–201. PMID:

33655719.

3. Lee JM, Doh JH, Nam CW, Shin ES, Koo BK. Functional approach for coronary artery disease: filling the gap between evidence and practice. Korean Circ J. 2018; 48:179–190. PMID:

29557104.

4. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020; 41:407–477. PMID:

31504439.

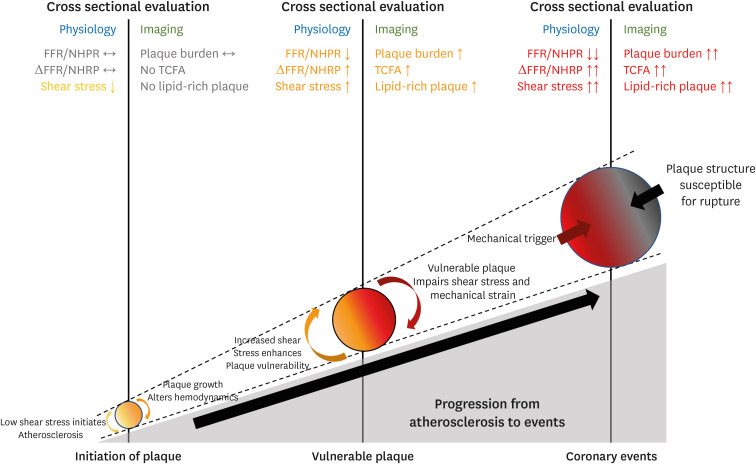

5. Tomaniak M, Katagiri Y, Modolo R, et al. Vulnerable plaques and patients: state-of-the-art. Eur Heart J. 2020; 41:2997–3004. PMID:

32402086.

6. Lee KY, Chang K. Understanding vulnerable plaques: current status and future directions. Korean Circ J. 2019; 49:1115–1122. PMID:

31760703.

7. Yang S, Koo BK, Narula J. Interactions between morphological plaque characteristics and coronary physiology: from pathophysiological basis to clinical implications. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022; 15:1139–1151. PMID:

34922863.

8. Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022; 145:e153–e639. PMID:

35078371.

9. Falk E, Shah PK, Fuster V. Coronary plaque disruption. Circulation. 1995; 92:657–671. PMID:

7634481.

10. Otsuka F, Joner M, Prati F, Virmani R, Narula J. Clinical classification of plaque morphology in coronary disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014; 11:379–389. PMID:

24776706.

11. Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47:C13–C18. PMID:

16631505.

12. Li J, Montarello NJ, Hoogendoorn A, et al. Multimodality intravascular imaging of high-risk coronary plaque. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022; 15:145–159. PMID:

34023267.

13. Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:226–235. PMID:

21247313.

14. Erlinge D, Maehara A, Ben-Yehuda O, et al. Identification of vulnerable plaques and patients by intracoronary near-infrared spectroscopy and ultrasound (PROSPECT II): a prospective natural history study. Lancet. 2021; 397:985–995. PMID:

33714389.

15. Prati F, Romagnoli E, Gatto L, et al. Relationship between coronary plaque morphology of the left anterior descending artery and 12 months clinical outcome: the CLIMA study. Eur Heart J. 2020; 41:383–391. PMID:

31504405.

16. Chang HJ, Lin FY, Lee SE, et al. Coronary Atherosclerotic Precursors of Acute Coronary Syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71:2511–2522. PMID:

29852975.

17. Tian J, Dauerman H, Toma C, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of TCFA and degree of coronary artery stenosis: an OCT, IVUS, and angiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 64:672–680. PMID:

25125298.

18. Araki M, Soeda T, Kim HO, et al. Spatial distribution of vulnerable plaques: comprehensive in vivo coronary plaque mapping. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020; 13:1989–1999. PMID:

32912472.

19. Cheng JM, Garcia-Garcia HM, de Boer SP, et al. In vivo detection of high-risk coronary plaques by radiofrequency intravascular ultrasound and cardiovascular outcome: results of the ATHEROREMO-IVUS study. Eur Heart J. 2014; 35:639–647. PMID:

24255128.

20. Schuurman AS, Vroegindewey MM, Kardys I, et al. Prognostic value of intravascular ultrasound in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:2003–2011. PMID:

30336823.

21. Kaul S, Narula J. In search of the vulnerable plaque: is there any light at the end of the catheter? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 64:2519–2524. PMID:

25500238.

22. Gijsen F, Katagiri Y, Barlis P, et al. Expert recommendations on the assessment of wall shear stress in human coronary arteries: existing methodologies, technical considerations, and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40:3421–3433. PMID:

31566246.

23. Malek AM, Alper SL, Izumo S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. JAMA. 1999; 282:2035–2042. PMID:

10591386.

24. Yahagi K, Kolodgie FD, Otsuka F, et al. Pathophysiology of native coronary, vein graft, and in-stent atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016; 13:79–98. PMID:

26503410.

25. Fukumoto Y, Hiro T, Fujii T, et al. Localized elevation of shear stress is related to coronary plaque rupture: a 3-dimensional intravascular ultrasound study with in-vivo color mapping of shear stress distribution. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 51:645–650. PMID:

18261684.

26. Gijsen FJ, Wentzel JJ, Thury A, et al. Strain distribution over plaques in human coronary arteries relates to shear stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008; 295:H1608–H1614. PMID:

18621851.

27. Samady H, Eshtehardi P, McDaniel MC, et al. Coronary artery wall shear stress is associated with progression and transformation of atherosclerotic plaque and arterial remodeling in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2011; 124:779–788. PMID:

21788584.

28. Kolpakov V, Gordon D, Kulik TJ. Nitric oxide-generating compounds inhibit total protein and collagen synthesis in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1995; 76:305–309. PMID:

7834842.

29. Casey PJ, Dattilo JB, Dai G, et al. The effect of combined arterial hemodynamics on saphenous venous endothelial nitric oxide production. J Vasc Surg. 2001; 33:1199–1205. PMID:

11389418.

30. Kenagy RD, Fischer JW, Davies MG, et al. Increased plasmin and serine proteinase activity during flow-induced intimal atrophy in baboon PTFE grafts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002; 22:400–404. PMID:

11884281.

31. Bark DL Jr, Ku DN. Wall shear over high degree stenoses pertinent to atherothrombosis. J Biomech. 2010; 43:2970–2977. PMID:

20728892.

32. Choi G, Lee JM, Kim HJ, et al. Coronary artery axial plaque stress and its relationship with lesion geometry: application of computational fluid dynamics to coronary CT angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015; 8:1156–1166. PMID:

26363834.

33. Tanaka A, Imanishi T, Kitabata H, et al. Morphology of exertion-triggered plaque rupture in patients with acute coronary syndrome: an optical coherence tomography study. Circulation. 2008; 118:2368–2373. PMID:

19015405.

34. Stone PH, Coskun AU, Kinlay S, et al. Effect of endothelial shear stress on the progression of coronary artery disease, vascular remodeling, and in-stent restenosis in humans: in vivo 6-month follow-up study. Circulation. 2003; 108:438–444. PMID:

12860915.

35. Stone PH, Saito S, Takahashi S, et al. Prediction of progression of coronary artery disease and clinical outcomes using vascular profiling of endothelial shear stress and arterial plaque characteristics: the PREDICTION Study. Circulation. 2012; 126:172–181. PMID:

22723305.

36. Corban MT, Eshtehardi P, Suo J, et al. Combination of plaque burden, wall shear stress, and plaque phenotype has incremental value for prediction of coronary atherosclerotic plaque progression and vulnerability. Atherosclerosis. 2014; 232:271–276. PMID:

24468138.

37. Stone PH, Maehara A, Coskun AU, et al. Role of low endothelial shear stress and plaque characteristics in the prediction of nonculprit major adverse cardiac events: the PROSPECT study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018; 11:462–471. PMID:

28917684.

38. Bajraktari A, Bytyçi I, Henein MY. High coronary wall shear stress worsens plaque vulnerability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Angiology. 2021; 72:706–714. PMID:

33535802.

39. Hartman EMJ, De Nisco G, Kok AM, et al. Wall shear stress-related plaque growth of lipid-rich plaques in human coronary arteries: an near-infrared spectroscopy and optical coherence tomography study. Cardiovasc Res. 2023; 119:1021–1029. PMID:

36575921.

40. Varshney AS, Coskun AU, Siasos G, et al. Spatial relationships among hemodynamic, anatomic, and biochemical plaque characteristics in patients with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2021; 320:98–104. PMID:

33468315.

41. Kelsey LJ, Bellinge JW, Majeed K, et al. Low endothelial shear stress is associated with high-risk coronary plaque features and microcalcification activity. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021; 14:2262–2264. PMID:

34274284.

42. Okamoto N, Vengrenyuk Y, Fuster V, et al. Relationship between high shear stress and OCT-verified thin-cap fibroatheroma in patients with coronary artery disease. PLoS One. 2020; 15:e0244015. PMID:

33332434.

43. Hetterich H, Jaber A, Gehring M, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography based assessment of endothelial shear stress and its association with atherosclerotic plaque distribution in-vivo. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0115408. PMID:

25635397.

44. Park JB, Choi G, Chun EJ, et al. Computational fluid dynamic measures of wall shear stress are related to coronary lesion characteristics. Heart. 2016; 102:1655–1661. PMID:

27302987.

45. Kay FU, Canan A, Abbara S. Future directions in coronary CT angiography: CT-fractional flow reserve, plaque vulnerability, and quantitative plaque assessment. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:185–202. PMID:

31960635.

46. Dwivedi A, Al’Aref SJ, Lin FY, Min JK. Evaluation of atherosclerotic plaque in non-invasive coronary imaging. Korean Circ J. 2018; 48:124–133. PMID:

29441745.

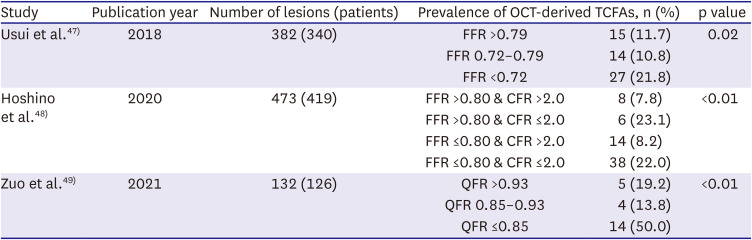

47. Usui E, Yonetsu T, Kanaji Y, et al. Optical coherence tomography-defined plaque vulnerability in relation to functional stenosis severity and microvascular dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018; 11:2058–2068. PMID:

30336810.

48. Hoshino M, Usui E, Sugiyama T, Kanaji Y, Yonetsu T, Kakuta T. Prevalence of OCT-defined high-risk plaque in relation to physiological characteristics by fractional flow reserve and coronary flow reserve. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2020; 73:331–332. PMID:

31672561.

49. Zuo W, Sun R, Zhang X, et al. The association between quantitative flow ratio and intravascular imaging-defined vulnerable plaque characteristics in patients with stable angina and non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021; 8:690262. PMID:

34277736.

50. Yang S, Hoshino M, Koo BK, et al. Relationship of plaque features at coronary CT to coronary hemodynamics and cardiovascular events. Radiology. 2022; 305:578–587. PMID:

35972355.

51. Driessen RS, Stuijfzand WJ, Raijmakers PG, et al. Effect of plaque burden and morphology on myocardial blood flow and fractional flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71:499–509. PMID:

29406855.

52. Yang S, Koo BK, Hoshino M, et al. CT angiographic and plaque predictors of functionally significant coronary disease and outcome using machine learning. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021; 14:629–641. PMID:

33248965.

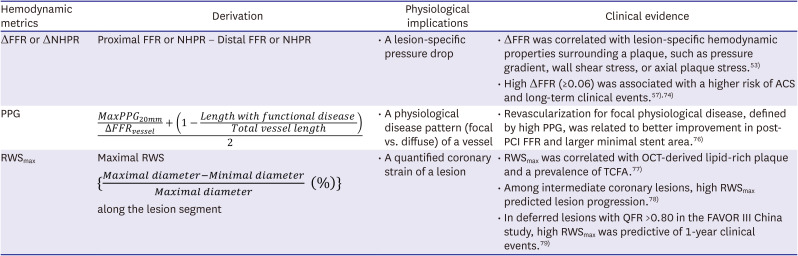

53. Yang S, Choi G, Zhang J, et al. Association among local hemodynamic parameters derived from CT angiography and their comparable implications in development of acute coronary syndrome. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021; 8:713835. PMID:

34589527.

54. Kalykakis GE, Antonopoulos AS, Pitsargiotis T, et al. Relationship of endothelial shear stress with plaque features with coronary CT angiography and vasodilating capability with PET. Radiology. 2021; 300:549–556. PMID:

34184936.

55. Wong CC, Javadzadegan A, Ada C, et al. Fractional flow reserve and instantaneous wave-free ratio predict pathological wall shear stress in coronary arteries: implications for understanding the pathophysiological impact of functionally significant coronary stenoses. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022; 11:e023502. PMID:

35043698.

56. Yang S, Koo BK. Physiology versus imaging-guided revascularization: where are we in 2023? JACC Asia. 2023.

57. Lee JM, Choi G, Koo BK, et al. Identification of high-risk plaques destined to cause acute coronary syndrome using coronary computed tomographic angiography and computational fluid dynamics. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019; 12:1032–1043. PMID:

29550316.

58. Fukuyama Y, Otake H, Seike F, et al. Potential relationship between high wall shear stress and plaque rupture causing acute coronary syndrome. Heart Vessels. 2023; 38:634–644. PMID:

36617625.

59. Thondapu V, Mamon C, Poon EK, et al. High spatial endothelial shear stress gradient independently predicts site of acute coronary plaque rupture and erosion. Cardiovasc Res. 2021; 117:1974–1985. PMID:

32832991.

60. Costopoulos C, Huang Y, Brown AJ, et al. Plaque rupture in coronary atherosclerosis is associated with increased plaque structural stress. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017; 10:1472–1483. PMID:

28734911.

61. Bourantas CV, Zanchin T, Torii R, et al. Shear stress estimated by quantitative coronary angiography predicts plaques prone to progress and cause events. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020; 13:2206–2219. PMID:

32417338.

62. Candreva A, Pagnoni M, Rizzini ML, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction based on endothelial shear stress analysis using coronary angiography. Atherosclerosis. 2022; 342:28–35. PMID:

34815069.

63. Kumar A, Thompson EW, Lefieux A, et al. High coronary shear stress in patients with coronary artery disease predicts myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:1926–1935. PMID:

30309470.

64. van de Hoef TP, Lee JM, Boerhout CK, et al. Combined assessment of FFR and CFR for decision making in coronary revascularization: from the multicenter international ILIAS registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022; 15:1047–1056. PMID:

35589234.

65. Zimmermann FM, Omerovic E, Fournier S, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided percutaneous coronary intervention vs. medical therapy for patients with stable coronary lesions: meta-analysis of individual patient data. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40:180–186. PMID:

30596995.

66. Koo BK, Hu X, Kang J, et al. Fractional flow reserve or intravascular ultrasonography to guide PCI. N Engl J Med. 2022; 387:779–789. PMID:

36053504.

67. Iannaccone M, Abdirashid M, Annone U, et al. Comparison between functional and intravascular imaging approaches guiding percutaneous coronary intervention: a network meta-analysis of randomized and propensity matching studies. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020; 95:1259–1266. PMID:

31400061.

68. Kedhi E, Berta B, Roleder T, et al. Thin-cap fibroatheroma predicts clinical events in diabetic patients with normal fractional flow reserve: the COMBINE OCT-FFR trial. Eur Heart J. 2021; 42:4671–4679. PMID:

34345911.

69. Fabris E, Berta B, Hommels T, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with normal fractional flow reserve and thin-cap fibroatheroma. EuroIntervention. 2023; 18:e1099–e1107. PMID:

36170036.

70. Lee JM, Choi KH, Koo BK, et al. Prognostic implications of plaque characteristics and stenosis severity in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 73:2413–2424. PMID:

31097161.

71. Cho YK, Hwang J, Lee CH, et al. Influence of anatomical and clinical characteristics on long-term prognosis of FFR-guided deferred coronary lesions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020; 13:1907–1916. PMID:

32819479.

72. Park J, Lee JM, Koo BK, et al. Relevance of anatomical, plaque, and hemodynamic characteristics of non-obstructive coronary lesions in the prediction of risk for acute coronary syndrome. Eur Radiol. 2019; 29:6119–6128. PMID:

31025066.

73. Yang S, Koo BK, Hwang D, et al. High-risk morphological and physiological coronary disease attributes as outcome markers after medical treatment and revascularization. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021; 14:1977–1989. PMID:

34023270.

74. Yang S, Lesina K, Doh JH, et al. Long-term prognostic implications of hemodynamic and plaque assessment using coronary CT angiography. Atherosclerosis. 2023; 373:58–65. PMID:

36872186.

75. Collet C, Sonck J, Vandeloo B, et al. Measurement of hyperemic pullback pressure gradients to characterize patterns of coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 74:1772–1784. PMID:

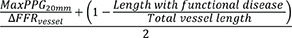

31582137.

76. Mizukami T, Sonck J, Sakai K, et al. Procedural outcomes after percutaneous coronary interventions in focal and diffuse coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022; 11:e026960. PMID:

36444858.

77. Hong H, Li C, Gutiérrez-Chico JL, et al. Radial wall strain: a novel angiographic measure of plaque composition and vulnerability. EuroIntervention. 2022; 18:1001–1010. PMID:

36073027.

78. Wang ZQ, Xu B, Li CM, et al. Angiography-derived radial wall strain predicts coronary lesion progression in non-culprit intermediate stenosis. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2022; 19:937–948. PMID:

36632201.

79. Tu S, Xu B, Chen L, et al. Short-term risk stratification of non-flow-limiting coronary stenosis by angiographically derived radial wall strain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023; 81:756–767. PMID:

36813375.

along the lesion segment

along the lesion segment

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download