1. Graves KD, Arnold SM, Love CL, Kirsh KL, Moore PG, Passik SD. Distress screening in a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic: prevalence and predictors of clinically significant distress. Lung Cancer. 2007; 55(2):215–224. PMID:

17084483.

2. Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001; 10(1):19–28. PMID:

11180574.

3. Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, Goodey E, Koopmans J, Lamont L, et al. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004; 90(12):2297–2304. PMID:

15162149.

4. Hopwood P, Stephens RJ. Depression in patients with lung cancer: prevalence and risk factors derived from quality-of-life data. J Clin Oncol. 2000; 18(4):893–903. PMID:

10673533.

5. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363(8):733–742. PMID:

20818875.

6. Park B, Youn S, Yi KK, Lee SY, Lee JS, Chung S. The prevalence of depression among patients with the top ten most common cancers in South Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2017; 14(5):618–625.

7. Park B, Youn S, Hann CW, Yi K, Lee S, Lee JS, et al. Prevalence of insomnia among patients with the ten most common cancers in South Korea: health insurance review and assessment service-national patient sample. Sleep Med Rev. 2016; 7(2):48–54.

8. Walker J, Hansen CH, Martin P, Symeonides S, Ramessur R, Murray G, et al. Prevalence, associations, and adequacy of treatment of major depression in patients with cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of routinely collected clinical data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014; 1(5):343–350. PMID:

26360998.

9. Davidson JR, MacLean AW, Brundage MD, Schulze K. Sleep disturbance in cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 2002; 54(9):1309–1321. PMID:

12058848.

10. Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, Mireskandari S, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013; 7(3):300–322. PMID:

23475398.

11. Myers SB, Manne SL, Kissane DW, Ozga M, Kashy DA, Rubin S, et al. Social-cognitive processes associated with fear of recurrence among women newly diagnosed with gynecological cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2013; 128(1):120–127. PMID:

23088925.

12. Savard J, Ivers H. The evolution of fear of cancer recurrence during the cancer care trajectory and its relationship with cancer characteristics. J Psychosom Res. 2013; 74(4):354–360. PMID:

23497839.

13. Dankert A, Duran G, Engst-Hastreiter U, Keller M, Waadt S, Henrich G, et al. Fear of progression in patients with cancer, diabetes mellitus and chronic arthritis. Rehabilitation (Stuttg). 2003; 42(3):155–163. PMID:

12813652.

14. Koch L, Jansen L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (≥ 5 years) cancer survivors--a systematic review of quantitative studies. Psychooncology. 2013; 22(1):1–11.

15. Herschbach P, Dinkel A. Fear of progression. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2014; 197:11–29. PMID:

24305766.

16. Haun MW, Sklenarova H, Villalobos M, Thomas M, Brechtel A, Löwe B, et al. Depression, anxiety and disease-related distress in couples affected by advanced lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014; 86(2):274–280. PMID:

25294732.

17. Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Kim AW, Tanoue LT. The eighth edition lung cancer stage classification. Chest. 2017; 151(1):193–203. PMID:

27780786.

18. Theobald DE. Cancer pain, fatigue, distress, and insomnia in cancer patients. Clin Cornerstone. 2004; 6(Suppl 1D):S15–S21. PMID:

15675653.

19. Induru RR, Walsh D. Cancer-related insomnia. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014; 31(7):777–785. PMID:

24142594.

20. Büttner-Teleagă A, Kim YT, Osel T, Richter K. Sleep disorders in cancer-a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11696. PMID:

34770209.

21. Davis MP, Goforth HW. Long-term and short-term effects of insomnia in cancer and effective interventions. Cancer J. 2014; 20(5):330–344. PMID:

25299143.

22. Huo Z, Ge F, Li C, Cheng H, Lu Y, Wang R, et al. Genetically predicted insomnia and lung cancer risk: a Mendelian randomization study. Sleep Med. 2021; 87:183–190. PMID:

34627121.

23. Maguire R, Drummond FJ, Hanly P, Gavin A, Sharp L. Problems sleeping with prostate cancer: exploring possible risk factors for sleep disturbance in a population-based sample of survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2019; 27(9):3365–3373. PMID:

30627919.

24. Cho E, Lee D, Cho IK, Lee J, Ahn J, Bang YR. Insomnia mediate the influence of reassurance-seeking behavior and viral anxiety on preoccupation with COVID-19 among the general population. Sleep Med Rev. 2022; 13(2):68–74.

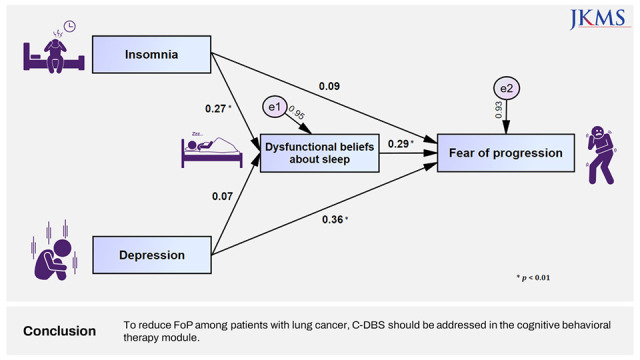

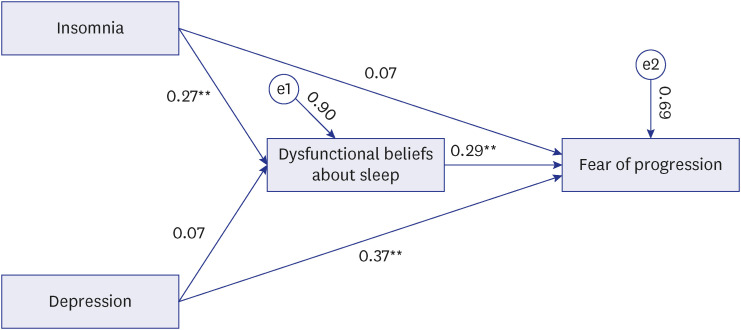

25. Chung S, Youn S, Choi B. Assessment of cancer-related dysfunctional beliefs about sleep for evaluating sleep disturbance in cancer patients. Sleep Med Rev. 2017; 8(2):98–101.

26. Belanger L, Savard J, Morin CM. Clinical management of insomnia using cognitive therapy. Behav Sleep Med. 2006; 4(3):179–198. PMID:

16879081.

27. Ong JC, Ulmer CS, Manber R. Improving sleep with mindfulness and acceptance: a metacognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2012; 50(11):651–660. PMID:

22975073.

28. Rumble ME, Keefe FJ, Edinger JD, Porter LS, Garst JL. A pilot study investigating the utility of the cognitive-behavioral model of insomnia in early-stage lung cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005; 30(2):160–169. PMID:

16125031.

29. Lee JH, Jeong JH, Ji W, Lee HJ, Lee Y, Jo MW, et al. Comparative effectiveness of smartphone healthcare applications for improving quality of life in lung cancer patients: study protocol. BMC Pulm Med. 2022; 22(1):175. PMID:

35501757.

30. Herschbach P, Berg P, Dankert A, Duran G, Engst-Hastreiter U, Waadt S, et al. Fear of progression in chronic diseases: psychometric properties of the fear of progression questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2005; 58(6):505–511. PMID:

16125517.

31. Shim EJ, Shin YW, Oh DY, Hahm BJ. Increased fear of progression in cancer patients with recurrence. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010; 32(2):169–175. PMID:

20302991.

32. Kwakkenbos L, van den Hoogen FH, Custers J, Prins J, Vonk MC, van Lankveld WG, et al. Validity of the fear of progression questionnaire-short form in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012; 64(6):930–934. PMID:

22262505.

33. Mehnert A, Herschbach P, Berg P, Henrich G, Koch U. Fear of progression in breast cancer patients--validation of the short form of the fear of progression questionnaire (FoP-Q-SF). Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2006; 52(3):274–288. PMID:

17156600.

34. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(9):606–613. PMID:

11556941.

36. Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The insomnia severity index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep . 2011; 34(5):601–608. PMID:

21532953.

37. Cho YW, Song ML, Morin CM. Validation of a Korean version of the insomnia severity index. J Clin Neurol. 2014; 10(3):210–215. PMID:

25045373.

38. Berrett-Abebe J, Cadet T, Pirl W, Lennes I. Exploring the relationship between fear of cancer recurrence and sleep quality in cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2015; 33(3):297–309. PMID:

25751193.

39. Yeo S, Lee J, Kim K, Kim HJ, Chung S. Depression, rather than cancer-related fatigue or insomnia, decreased the quality of life of cancer patients. Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53(3):641–649. PMID:

33421982.

40. Kim I, Yi K, Lee J, Kim K, Youn S, Suh S, et al. Dysfunctional beliefs about sleep in cancer patients can mediate the effect of fear of progression on nsomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2019; 10(2):83–89.

41. Taylor TR, Huntley ED, Makambi K, Sween J, Adams-Campbell LL, Frederick W, et al. Understanding sleep disturbances in African-American breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. Psychooncology. 2012; 21(8):896–902. PMID:

21648016.

42. Wang X, Li M, Shi Q, Ji H, Kong S, Zhu L, et al. Fear of progression, anxiety, and depression in patients with advanced melanoma in the COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 era. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 13:880978. PMID:

35558429.

43. Hanprasertpong J, Geater A, Jiamset I, Padungkul L, Hirunkajonpan P, Songhong N. Fear of cancer recurrence and its predictors among cervical cancer survivors. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017; 28(6):e72. PMID:

28758378.

44. Mahendran R, Liu J, Kuparasundram S, Simard S, Chan YH, Kua EH, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence among cancer survivors in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2021; 62(6):305–310. PMID:

31989183.

45. Ruel S, Ivers H, Savard MH, Gouin JP, Lemieux J, Provencher L, et al. Insomnia, immunity, and infections in cancer patients: results from a longitudinal study. Health Psychol. 2020; 39(5):358–369. PMID:

31855038.

46. Chen Y, Tan F, Wei L, Li X, Lyu Z, Feng X, et al. Sleep duration and the risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis including dose-response relationship. BMC Cancer. 2018; 18(1):1149. PMID:

30463535.

47. Ha DM, Prochazka AV, Bekelman DB, Stevens-Lapsley JE, Studts JL, Keith RL. Modifiable factors associated with health-related quality of life among lung cancer survivors following curative intent therapy. Lung Cancer. 2022; 163:42–50. PMID:

34896804.

48. Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G, Mutsaers B, Thewes B, Prins J, et al. From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2016; 24(8):3265–3268. PMID:

27169703.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download