DISCUSSION

Arachnoid cysts are extra-axial cystic lesions with walls composed of arachnoid membrane and filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or CSF-like fluid. The prevalence of arachnoid cysts is higher among males with 81.3% [

7]. The underlying pathogenic mechanism of arachnoid cysts is not entirely clear, but the most widely accepted theory is that arachnoid cysts result from abnormal development of the subarachnoid space during the splitting of the primitive perimedullary mesh by CSF flow [

3]. There are 3 hypotheses that attempt to explain the pathophysiology of cyst growth: the active pump (secretion), valve mechanism, and oncotic pressure hypotheses [

1]. Arachnoid cysts can develop in any part of the intracranial space, but the middle cranial fossa—which houses about half of these lesions—is the most commonly affected site. Other relatively frequent arachnoid cyst sites are the cerebral convexities, quadrigeminal cistern, cerebellopontine angle, suprasellar cistern, and cisterna magna [

345]. Arachnoid cysts are usually asymptomatic and can be found incidentally. However, modern neuroimaging technologies have facilitated increased diagnosis of arachnoid cysts. Many such cysts are incidentally identified by CT or magnetic resonance images captured in the workup of conditions, most commonly head injuries [

349]. Associated symptoms and signs vary by cyst site but can include headaches, seizures, and neurologic deficits.

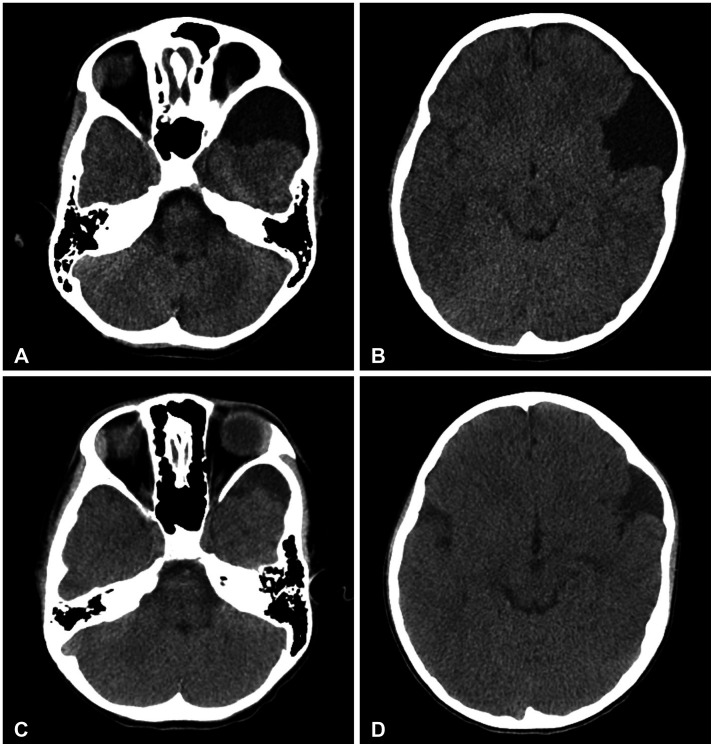

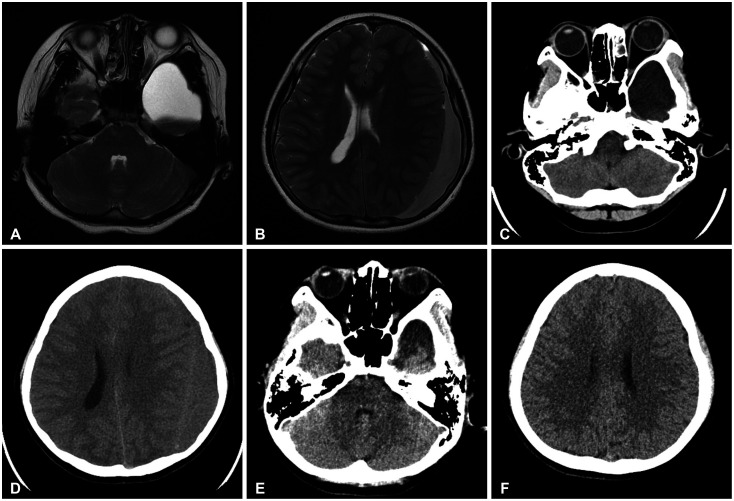

Although arachnoid cysts are benign lesions, they could be associated with some changes that may occur spontaneously or after head trauma. Cysts can enlarge or rupture. Rupture is a rare complication of arachnoid cysts, with an incidence reported to be in the 2.3%–4.6% range [

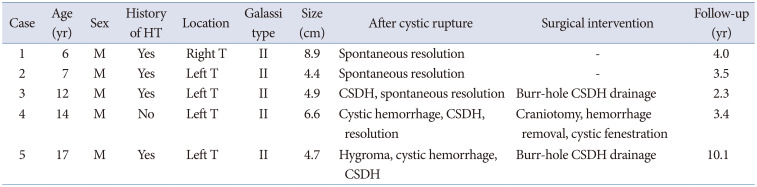

5610]. At our institution, 5 patients (1.3%) were diagnosed with ruptured arachnoid cysts among 388 patients encountered with arachnoid cysts during the investigated time frame. Importantly, there may have been more ruptured arachnoid cysts that were just not discovered. Ruptured arachnoid cysts can resolve spontaneously. They can also be associated with subdural hygroma formation and hemorrhagic complications (subdural or intracystic hematomas, for example). Larger arachnoid cysts (with diameters >5 cm) and head injury are widely accepted risk factors for arachnoid cyst rupture with hemorrhagic complications [

257]. Some studies have demonstrated arachnoid cyst location (in the middle cranial fossa) to be a statistically significant risk factor for cyst rupture [

5]. Children, adolescents, and young adults with intracranial arachnoid cysts are at the greatest risk for arachnoid cyst–associated hemorrhage [

67911]. An undetected arachnoid cyst rupture should be considered in the context of a child or young adult presenting with a chronic subdural hematoma. The mechanism underlying arachnoid cyst rupture has not been definitively established. Two mechanisms have been proposed, however [

3689]. The first theory is that arachnoid cyst rupture is associated with the rupture of bridging veins or vessels in the cyst wall, owing to the easy transfer of pressure through the cyst [

3]. The second theory is that the lower compliance of arachnoid cysts compared with that of normal brain tissue reduces intracalvarial cushioning following mild trauma.

There is no consensus on the optimal treatment of ruptured arachnoid cysts, which depends on the symptom pattern and cyst location. Observation is possible in most patients with no symptoms or mild symptoms because arachnoid cysts associated with subdural or epidural hematomas may also spontaneously resolve [

7891213]. If arachnoid cysts do not resolve spontaneously, burr-hole subdural drainage, craniotomy and cyst fenestration, and endoscopic cyst fenestration are the neurosurgical options [

910]. Burr-hole drainage of chronic subdural hematomas that avoids manipulation of the arachnoid cyst should be the first-line surgical procedure for patients with neurological symptoms. However, simple drainage of chronic subdural hematomas is not sufficient for some patients who experience hematoma recurrence (incidence, 8.2%) [

37]. Craniotomy and cyst fenestration is another option for patients with a risk of recurrence; only 1.5% of those who undergo this procedure experience hematoma recurrence [

78]. However, craniotomy and cyst fenestration is associated with relatively high rates of morbidity (10%–15%) and mortality (1%) [

414]. Endoscopic cyst fenestration is another treatment option [

3715]. The choice between cyst removal and simple burr-hole subdural drainage remains controversial.

At our institution, 5 patients with ruptured arachnoid cysts were treated between January 2004 and July 2020. Two of them experienced spontaneous resolution without hemorrhage throughout the follow-up period. One patient with a chronic subdural hematoma underwent burr-hole drainage. Craniotomy, hematoma removal, and cystic fenestration were performed on a patient with cystic hemorrhage and chronic subdural hematoma. The last patient—with subdural hygroma development, cystic hemorrhage, and chronic subdural hemorrhage formation—underwent burr-hole hemorrhage drainage. All of our patients were symptom-free postoperatively, and no neurological symptoms or signs were reported or observed during follow-up.

As the study’s limitations, our patient sample size was small. Also, fewer detected cases in our study may result from undetected rupture in asymptomatic arachnoid cyst patients, due to infrequent radiologic check-ups.

In conclusion, arachnoid cysts are benign intracranial lesions that rarely rupture. Observation is recommended for asymptomatic cysts. Some cases associated with hemorrhage require surgical intervention, and there is a favorable prognosis postoperatively.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download