This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Meningioma is the most common brain tumor among all histologically reported malignant and non-malignant tumors of the central nervous system. Angiomatous meningioma is one of the subtypes of meningioma that is rarely reported. In this paper, we present a case of a 67-year-old female patient who sought consultation due to seizure, cognitive decline, and parkinsonism. Contrast-enhanced MRI showed a well-defined tumor in the left frontal lobe convexity with extensive perilesional edema. A tumor excision was done and histopathology studies revealed an angiomatous meningioma subtype. This case is reportable because angiomatous meningioma is a recognized rare entity. It is important to share this entity with other medical professionals and start to consider this condition in differential diagnosis when diagnosing a patient with an intracranial mass with an extensive peritumoral edema. Furthermore, the patient’s unusual presentation of parkinsonian features and its occurrence with colorectal cancer history suggest a possible association between these conditions.

Keywords: Angiomatous meningioma, Central nervous system neoplasms, Colorectal neoplasm, Neoplasms, Research

INTRODUCTION

Meningioma comprises 38.3% of the overall histologically reported combined malignant and non-malignant tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) [

1]. Among the subtypes of meningioma, 2.1% accounted for the angiomatous meningioma subtype [

2]. Limited studies are cited describing angiomatous meningioma; to date, there are no reports describing patients who manifest parkinsonian features. Moreover, there are no data reported on its occurrence in patients with a history of colorectal cancer.

CASE REPORT

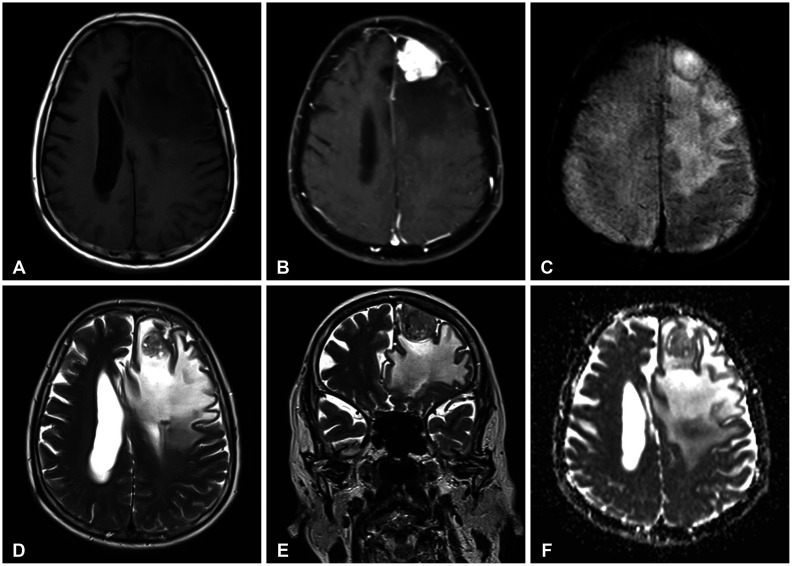

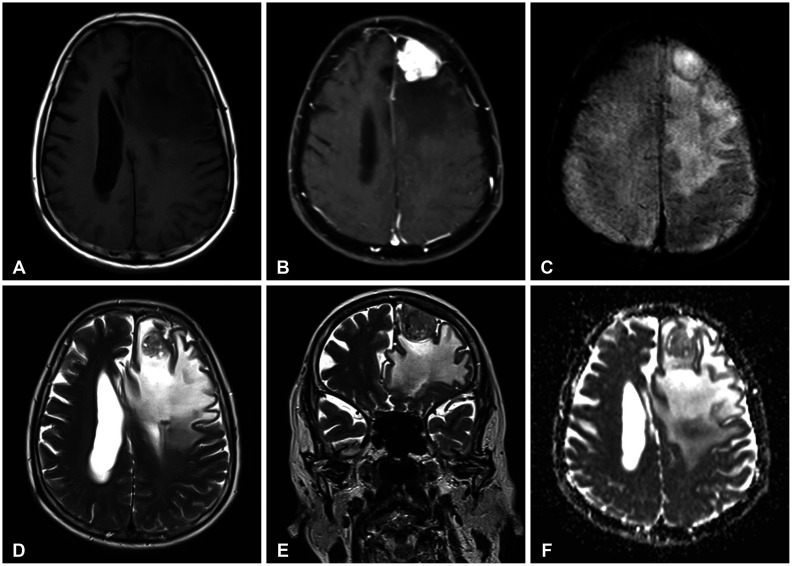

Two years before the consult, a 67-year-old female patient developed resting tremors in both hands, bradykinesia, rigidity of the extremities, and a masked fascie. These were associated with hemiparesis of the right arm and leg, unwitnessed falls, loss of consciousness, and memory lapses. She was brought to the ER due to a seizure. On routine history, it was noted that she had a history of colorectal cancer stage IIIA 11 years prior consult wherein she only received surgery. Adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and further workup such as positron-emission tomography CT scan were not done. The patient garnered a score of 4 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test and a score of 7 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Epileptiform discharges in the left centroparietal areas were seen in her 21-channel electroencephalogram (EEG). On MRI, a well-defined tumor mass lesion was seen in the left frontal lobe which measured 3×2.8×3.4 cm. The tumor appeared isointense on the T1-weighted (T1W) image (

Fig. 1A). Moreover, there was enhancement of the tumor in the T1W with contrast sequence and it further showed that the tumor abuts the dura and shifting towards the right hemisphere (

Fig. 1B). No magnetic susceptibility defect in the susceptibility-weighted image (SWI) sequence was noted (

Fig. 1C). Signal flow voids in blood vessels and marked edema surrounding the tumor was seen in the T2-weighted (TW2) sequences (

Fig. 1D and E). This vasogenic edema compressed the left frontal horn of the lateral ventricle. The region did not show abnormally low apparent diffusion coefficient values (

Fig. 1F). Medical treatment included intravenous dexamethasone for decompression and an antiepileptic drug for seizure control.

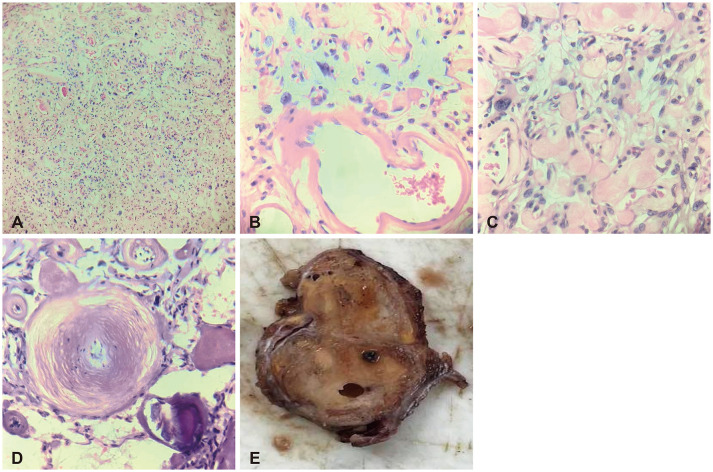

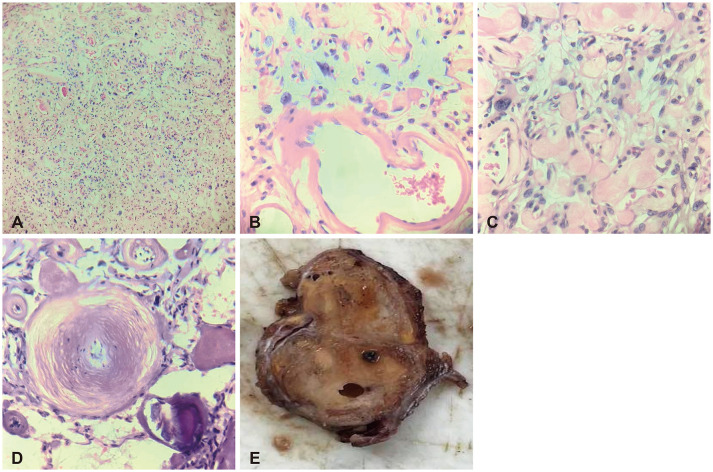

Considering a retrospective bias with the patient’s previous history of colorectal cancer, a diagnostic dilemma became inevitably present. We suspected a metastatic brain disease rather than a benign CNS tumor. A metastatic workup was done and did not show the presence of suspicious tumor growth in the chest and abdominopelvic areas. The case proceeded to the surgical removal of the tumor. Gross features consisted of tan-yellow to dark brown, ovoid, doughy tissue, and cut sections showed variegated tan-white to the yellow surface with areas of hemorrhages (

Fig. 2E). The microscopic section of the specimen showed an encapsulated tumor composed of numerous vascular spaces of varying caliber with intervening oval and round tumor cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyaline globules within spaces. Some tumor cells displayed degenerative nuclear atypia with intranuclear pseudo-inclusions. This occupied more than 50% of the tumoral area. There are numerous psammoma bodies present on the periphery of the tumor. No mitotic activity is seen (

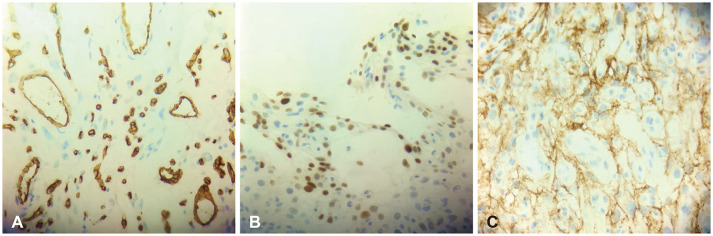

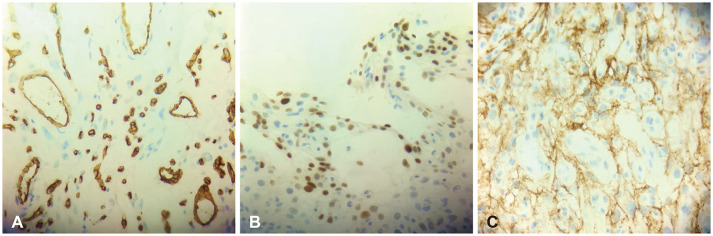

Fig. 2A-D). We, therefore, concluded that the tumor was a meningioma. To rule out hemangioblastoma and solitary fibrous tumor, an immunohistochemistry workup was done. There was a positive expression of epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and progesterone receptor on the tumor cells, but negative staining for CD34. These helped us establish the diagnosis of an angiomatous subtype of meningioma, World Health Organization (WHO) classification of grade 1 (

Fig. 3).

The perioperative status was uneventful and Simpson grade I resection of the tumor was achieved. Clinical follow-up was made a month after discharge and there was a notable improvement in the rigidity of extremities, bradyphrenia, masked fascie, and weakness of the right arm and leg.

DISCUSSION

Meningiomas are benign and generally slow-growing tumors of the CNS that originate from arachnoid cap cells that exist on the surface covering the brain and the spinal cord [

34]. The WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System, 5th edition (WHO CNS5) discussed the differences between the 15 subtypes of meningioma [

5]. Angiomatous meningiomas have a relatively low incidence accounting for only 1.85%–2.59% out of all types of meningiomas [

467]. Case series and reports available stated vast clinical manifestations but none among them reported parkinsonian features that our patient presented.

Angiomatous meningiomas on MRI are hypointense on T1W sequences and are hyperintense on T2W sequences [

78]. Previous case series and analyses described radiological features of angiomatous meningioma to be commonly found in the cerebral convexity and present with homogenous enhancement on MRI, occurring with a dural tail sign, and prominent signal flow voids [

9]. This tumor is often associated with more severe cerebral edema than would be expected for its size. Other subtypes of meningioma presenting with extensive peritumoral edema are secretory and microcystic meningiomas [

10].

In histopathology studies in angiomatous meningiomas, features include the abundance of numerous blood vessels interspersed with small meningothelial cells and foamy spider-like cells [

47]. The blood vessel component is more than 50% of the tumoral architecture [

2]. There is a predominance of sinusoids or capillaries, with no note of cytological atypia prevailing on the background of an otherwise typical meningioma [

911]. The main differential diagnosis includes hemangioblastoma and solitary fibrous tumor. Hasselblatt et al. [

2] categorized angiomatous meningiomas into two subgroups based on vascular channel diameter, namely macrovascular (>50% of vessels bigger than 30 mm in diameter) and microvascular (>50% of vessels less than 30 mm in diameter). It is the microvascular subtype of angiomatous meningioma that is difficult to distinguish from hemangioblastoma and solitary fibrous tumor. In this case, we had no trouble distinguishing angiomatous meningioma from hemangioblastoma and solitary fibrous tumor on permanent tissue sections since the tumor focally exhibits the morphologic characteristic of a typical psammomatous variant of meningioma. The immunoreactivity pattern of angiomatous meningioma is identical to that of a typical meningioma. The tumor cells show immunoreactivity to the progesterone receptor and EMA but are negative for CD34. In contrast, vascular cells of hemangioblastoma and solitary fibrous tumors are immunoreactive to CD34 but tumor cells fail to stain progesterone receptors and EMA.

Surgical treatment is the mainstay of management to achieve Simpson grades I or II resections [

47]. However, there is a tumor recurrence rate of 4.30%–12.07% and was observed to be more prevalent with Simpson grades II and higher [

47]. This recurrence rate was reduced if surgery was followed by postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy [

8]. In contrast, there were preceding case series that did not recommend radiation, but rather suggested a second surgery for tumor recurrence [

47]. We, therefore, conclude that careful planning should be tailored to the patient’s unique case and that risks and benefits should be weighed.

In a cohort study, it was found that there was a significantly increased risk of developing meningioma in colorectal cancer patients. The result showed a standardized incidence ratio of 1.60, confidence interval 1.32–1.94. The increased risk was particularly seen in female patients [

12].

Therefore, we strongly recommend that a benign tumor such as the angiomatous meningioma be included as differential diagnosis in patients who present with an intracranial mass with extensive cerebral edema and that further investigations should be made in determining the possible association of meningioma in patients with history of primary malignancies elsewhere in the body. Further reports should also be done to describe and explain unusual manifestations of meningioma, just like in our case—parkinsonian features.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Bernadette R. Espiritu for lending her expertise knowledge in the histopathologic basis of diagnosing this case. Dr. Michael N. Sabalza for lending his expertise knowledge and skills during the surgical management of this case.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed during the study are included in this published article.

References

1. Ostrom QT, Patil N, Cioffi G, Waite K, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2013-2017. Neuro Oncol. 2020; 22(12 Suppl 2):iv1–iv96. PMID:

33123732.

2. Hasselblatt M, Nolte KW, Paulus W. Angiomatous meningioma: a clinicopathologic study of 38 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004; 28:390–393. PMID:

15104303.

3. Bansal D, Diwaker P, Gogoi P, Nazir W, Tandon A. Intraparenchymal angiomatous meningioma: a diagnostic dilemma. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015; 9:ED07–ED08.

4. Hua L, Luan S, Li H, Zhu H, Tang H, Liu H, et al. Angiomatous meningiomas have a very benign outcome despite frequent peritumoral edema at onset. World Neurosurg. 2017; 108:465–473. PMID:

28844928.

5. Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021; 23:1231–1251. PMID:

34185076.

6. Yang L, Ren G, Tang J. Intracranial angiomatous meningioma: a clinicopathological study of 23 cases. Int J Gen Med. 2020; 13:1653–1659. PMID:

33408502.

7. Ben Nsir A, Chabaane M, Krifa H, Jeme H, Hattab N. Intracranial angiomatous meningiomas: a 15-year, multicenter study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016; 149:111–117. PMID:

27513979.

8. Liu Z, Wang C, Wang H, Wang Y, Li JY, Liu Y. Clinical characteristics and treatment of angiomatous meningiomas: a report of 27 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013; 6:695–702. PMID:

23573316.

9. Hwang J, Kong DS, Seol HJ, Nam DH, Lee JI, Choi JW. Clinical and radiological characteristics of angiomatous meningiomas. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 2016; 4:94–99. PMID:

27867918.

10. WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Central nervous system tumours. 5th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer;2021.

11. Bodla AA, Mehta P, Mushtaq F, Durrani OM. Angiomatous meningioma of orbit mimicking as malignant neoplasm: a case report and literature review. Orbit. 2011; 30:183–185. PMID:

21780930.

12. Malmer B, Tavelin B, Henriksson R, Grönberg H. Primary brain tumours as second primary: a novel association between meningioma and colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2000; 85:78–81. PMID:

10585587.

Fig. 1

Neuroimaging MRI with contrast enhancement. A: The tumor lesion is isointense on the T1-weighted (T1W) sequence located at the left frontal lobe, measuring 3×2.8×3.4 cm. B: There are marked intense enhancements of the lesion after contrast as depicted in the T1W sequence. This abuts the dura and compresses the left frontal horn. C: Susceptibility-weighted image sequence does not show magnetic susceptibility. D and E: There are some signal voids of blood vessels seen in the T2-weighted sequences and it demonstrated marked surrounding edema. F: The region does not show abnormally low apparent diffusion coefficient values.

Fig. 2

Histopathologic and gross examination. A-D: Hematoxylin and eosin stain. A: Tumor composed of numerous vascular spaces and meningothelial cells (×100 magnification). B: Vascular spaces lined by endothelial cells with intervening areas of round to ovoid meningothelial cells. Some meningothelial cells are wrapped around the blood vessels, displaying degenerative nuclear atypia with intranuclear pseudo-inclusions (×400 magnification). C: Meningothelial cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and several hyaline globules within spaces (×400 magnification). D: Psammoma bodies demonstrating concentric calcifications (×400 magnification). E: Gross examination shows an encapsulated tumor (0.2-cm thick capsule) with a dark brown, smooth cut surface with punctate hemorrhages.

Fig. 3

Immunohistochemical study. A: Tumor cells show negative immunoreactivity for CD34 but positive for endothelial cells lining the blood vessels (CD34, ×400 magnification). B: Tumor cells show focal, strong nuclear expression on progesterone receptors (progesterone, ×400 magnification). C: Tumor cells exhibiting diffuse, strong, cytoplasmic staining on epithelial membrane antigen (EMA, ×400 magnification).

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download