Abstract

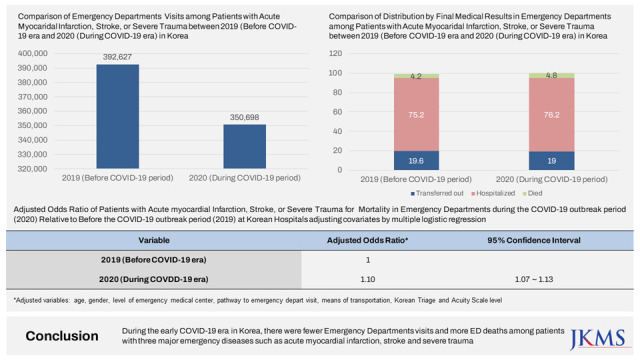

We aimed to investigate the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on admissions of patients with acute myocardial infarction, stroke, and severe trauma, and their excess mortality in emergency departments (EDs) in South Korea using registry data from the National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) for patients attending EDs of regional and local emergency medical centers. During the outbreak period of 2020, there were 350,698 ED visits, which was lower than the total in 2019 (392,627 visits). Multiple logistic regression revealed that, compared with 2019, there was significantly higher ED mortality rate during the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020 (adjusted odds ratio, 1.10; 95% confidence interval, 1.07–1.13). This finding implies that during the early outbreak period, people might have avoided seeking medical care even for acute and life-threatening conditions, or transfer times at the scene to the hospital arrival were delayed, or treatment for the patients in EDs were delayed.

Graphical Abstract

In Korea, the first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was detected on January 20, 2020. Since then, 29,665 people have died from the disease in Korea.1 As the COVID-19 outbreak carried on and expanded globally, the Korean government raised the national infectious disease crisis warning level to the highest level on February 23, 2020 (Serious, Red) and strengthened social distancing policies. Mask-wearing was mandated throughout Korea, as was social distancing of two arm lengths between individuals in public. Additionally, older people (aged 65 years and above) and high-risk groups were encouraged to avoid outings to the fullest extent possible.2 Patients with respiratory symptoms and fever were asked not to visit the hospital immediately; they were subjected to follow-up observations and COVID-19 testing after self-isolation.3 Emergency departments (EDs) in Korea were not prepared to accommodate the high influx of patients presenting with the new communicable disease. Many EDs were repeatedly closed for short periods as the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases increased, and medical staff and other patients in the ED were quarantined.4 It has taken additional time to search for a hospital to accept patients because the EDs were running out of capacity. Prehospital process times were delayed, including EMS arrival at the scene and hospital arrival.5 To prevent nosocomial transmission of COVID-19 and distinguish COVID-19 patients, simple interviews and screening tests were conducted in triage zone. These additional processes delayed hospital examinations and treatment.6 This had a drastically negative impact on the emergency medical services (EMS) as the emergency care of patients with fever was delayed, and the safety and care of all patients were threatened and disrupted.

Previous studies have analyzed the associations between the early COVID-19 pandemic, EMS, and urgent clinical outcomes of EMS. In Germany, a study investigating changes in admission patterns at EDs during a national lockdown (March through June 2020) following the onset of the pandemic found an average decline in admissions of 19%, compared with the same period in 2019.7 In the early phase of the pandemic, delays in emergency care for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), stroke or transient ischemic attacks, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, back pain, or mental and behavioral disorders due to use of alcohol could have led to a higher need for admissions later on.7 AMI-associated mortality increased by about 10% during the early COVID-19 outbreak (March and April 2020) owing to delays in treatment (particularly arising from delays between symptom onset and first medical contact) in Berlin, Germany.8 In England, according to a study that analyzed the databases of 180 acute National Health Service hospitals, during the early COVID-19 pandemic (March through May 2020), there was a substantial decline in admissions of patients with AMI, and the 30-day mortality associated with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) was higher than it was before the pandemic.9 In Denmark, the admission rate for patients with stroke or transient ischemic attacks decreased by 7% during the first lockdown (March and April 2020), and the 30-day mortality rate associated with all strokes was higher during this period (crude risk ratio, 1.30; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.59).10 In British Columbia, Canada, between 2019 and 2020, there was a 15% overall reduction in EMS calls extending to every health region in the province.11 EMS calls for all chief complaints decreased except for calls for dyspnea and anxiety, which increased significantly.11 Calls for critically ill patients with trauma, stroke, and ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) decreased by 9%.11 In the United States, excess cerebrovascular mortality occurred between March and May, 2020, including up to a 7.8% increase above expected levels during the week of April 18.12

Despite the challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, EMS must be prepared to respond appropriately to time-sensitive emergencies, including AMI, stroke, and severe trauma, and thus optimize patients with three major emergency diseases to all communities.13 We aimed to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency care utilization and mortality in Korea in 2020, in comparison with 2019. The National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) is an official nationwide database of ED visits in Korea. NEDIS reports have been released annually since 2013 by the National Emergency Medical Center of the National Medical Center.14 The NEDIS includes a nationwide registration system that captures clinical and administrative data for all ED visits. Data from almost all EDs in Korea are captured in the NEDIS reports: 408 of 413 EDs (98.8%) in 2016, 413 of 416 (99.3%) in 2017, 399 of 401 (99.5%) in 2018, 401 of 402 (99.8%) in 2019, and 403 of 403 (100%) in 2020.14

We analyzed NEDIS data for ED visits of regional and local emergency medical centers during the COVID-19 outbreak (from January 1 to December 31, 2020) and compared them with those of the previous year (from January 1 to December 31, 2019). We extracted the data of patients who met the ICD-10 criteria for a diagnosis of AMI (I21-I21.9) or stroke (I60-I60.9 or I61-I62.9 or I63-I64) or whose international classification of diseases injury severity scores (ICISS) were < 0.9, indicating severe trauma.

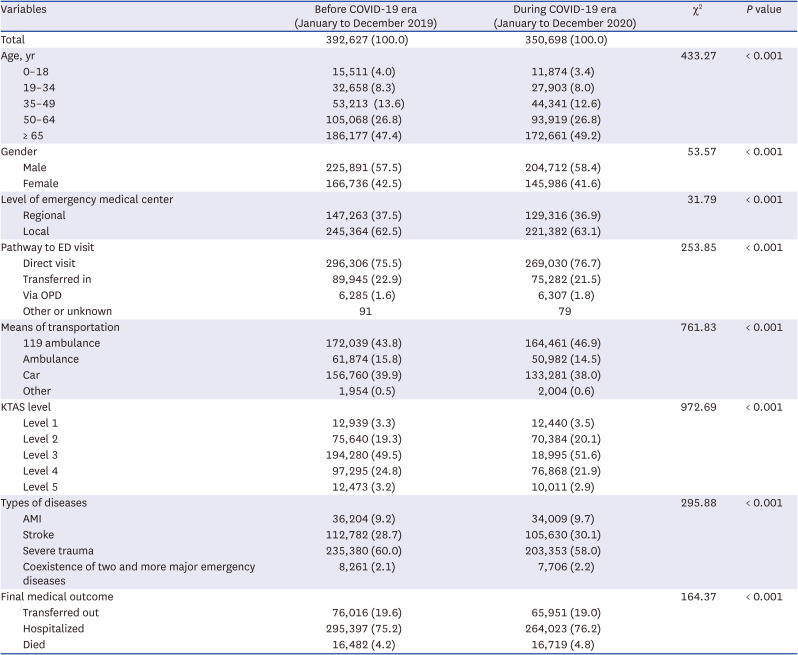

The analyzed variables were age, gender (male/female), level of emergency medical center (regional/local), pathway to ED visit (direct visit/transferred-in/via outpatient department), means of transportation (119 ambulance/ambulance/car), types of diseases (AMI, stroke, severe trauma and coexistence of diseases) and Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS) levels (1–5). The KTAS is a system used to triage patients who visit the ED, with higher scores indicating decreasing severity. Among severe emergency diseases managed for AMI, stroke, and severe trauma in 2020 and 2019, final medical outcomes were classified as transfers out, hospitalizations, or deaths and compared according to year.

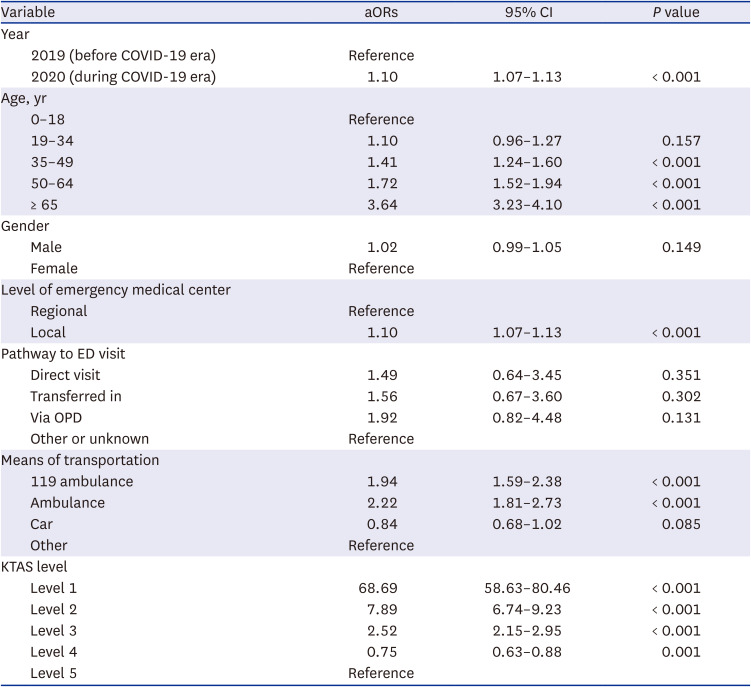

Descriptive statistics are presented, with categorical variables presented in terms of counts and percentages. Statistical significance was tested by χ2 analysis for differences between the years in terms of categorical variables (age, gender, level of emergency medical center, pathway to ED visit, means of transportation, KTAS level, distribution of three major emergency disease and final medical outcome). For the analysis of mortality, multiple logistic regression was conducted after adjusting for covariates (year, age, gender, level of emergency medical center, pathway to ED visit, means of transportation, and KTAS levels). Types of diseases were excluded from the multiple logistic model due to the multicollinearity with the KTAS levels. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R, version 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of ED visits for patients with three major emergency diseases of regional and local emergency medical centers in Korea in 2019 compared with those in 2020. The two periods were significantly different from one another in terms of all of the investigated variables. During the outbreak period of 2020, there were 350,698 ED visits, which was lower than the total in 2019 (392,627 visits). In 2020, the proportion of visits by patients aged ≥ 65 years was 49.2%, which was approximately 1.8% higher than the proportion in 2019 (47.4%). The proportion of visits by male patients significantly increased in 2020 relative to 2019. The proportion of visits to regional emergency medical center was 0.6% lower in 2020 than in 2019. In terms of the healthcare system navigation to the ED, most patients reached the ED via direct visits, with a 1.2% increase in 2020 (76.7%) compared with 2019 (75.5%). In 2020, nearly half of the visits were facilitated by 119 ambulance drop-offs (46.9%), with a 3.1% higher proportion relative to 2019. Conversely, the proportion of visits wherein patients arrived at the ED by car dropped between 2019 (39.9%) and 2020 (38.0%). In terms of KTAS level, the proportions of visits classified as level 1, 2, and 3 during the COVID-19 outbreak period increased by 0.2%, 0.8%, and 2.1% compared with 2019, respectively.

As shown in Table 1, ED visits in each major emergency disease also were lower in 2020 than those in 2019. The proportion of visits with final outcomes of transferred-out decreased by 0.6% in 2020 compared with 2019 (18.8% from 19.4%), while the mortality rate increased by 0.6% during the COVID-19 outbreak period compared with 2019 (4.8% from 4.2%, P < 0.001). Table 2 shows the multiple logistic regression analysis results for ED mortality among patients with three major emergency diseases in 2020 during the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. There was a significantly higher ED mortality rate in 2020 compared with 2019 (odds ratio, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.07–1.13; P < 0.001).

For patients with AMI, stroke, or severe trauma, during the outbreak period in 2020, there were 350,698 ED visits, which was lower than the 2019 total of 392,627. Regarding the final outcomes among these patients with three major emergency diseases, compared with 2019, the proportion of visits during which patients were transferred out decreased by 0.6%, and the proportion of visits during which patients died increased by 0.6% in 2020 relative to 2019. The COVID-19 outbreak in 2020 was significantly associated with ED mortality among these patients. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies.789101112 The plausible explanations for the increase in the mortalities of three major emergency diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic period of 2020 include the decreased healthcare-seeking behaviors by members of the general public for acute, life-threatening conditions, such as stroke, when strict social distancing was implemented,15 or delaying accident report of patients and transfer process of EMS personnel including arrival at the scene and hospital arrival when EDs were repeatedly closed for short periods (pre-hospital phase),5 or patients who should stay for ED until the results of COVID-19 screening tests in triage zone were checked before treatment in ED (in-hospital phase).6

Our study had several limitations. First, while most previous related studies considered the first half of 2020 as the early COVID-19 period, this study included all of 2020 in the outbreak period. Given that there was a rebound in EMS uptake for patients with AMI and stroke during the latter half of 2020,16 our study may have comparatively underestimated the epidemic-associated reduction in ED visits and increase in mortality. Second, we did not include other covariates such as residence of patients (urban vs rural) in multiple logistic models to examine the association between the mortality and the COVID-19 outbreak in 2000 and not consider the other periods such as 2018 and 2021 year. Third, during the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, the emergency patients with mild symptom were less likely to directly visit the EDs. Thus, it could contribute to the lower mortality in 2020 than in 2019. Fourth, we adjusted the severity of disease using the KTAS levels in multiple logistic models. However, given that KTAS was developed to triage patients who visit ED, it could not be sufficient to reflect the severity of severe emergency disease. Lastly, most previous studies analyzed mortality within 30 days after ED admission, but our study only analyzed mortality in the ED. These differences should be considered when comparing our findings with those of previous studies.

In conclusion, during the early COVID-19 era in Korea, there were fewer ED visits and more ED deaths among patients with three major emergency diseases, namely those with AMI, stroke, or severe trauma. It needs to be considered that timely EMSs are well prepared to deliver for severe emergency disease when strict social distancing measures are necessitated by infectious disease epidemics, and to educate patients on what to do during the pandemic.

References

1. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Coronavirus (COVID-19), Republic of Korea occurrence status. Accessed November 13, 2022.

https://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en/

.

2. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Korean government’s COVID-19 response system. Basic Guidelines for Distancing in Daily Life. Updated 2020. Accessed November 13, 2022.

https://ncov.kdca.go.kr/en/guidelineView.do?brdId=18&brdGubun=181&dataGubun=&ncvContSeq=2763&contSeq=2763&board_id=&gubun=

.

3. Kim SJ, Kim H, Park YH, Kang CY, Ro YS, Kim OH. Analysis of the impact of the coronavirus disease epidemic on the emergency medical system in South Korea using the Korean Triage and Acuity Scale. Yonsei Med J. 2021; 62(7):631–639. PMID: 34164961.

4. Lee DE, Ro YS, Ryoo HW, Moon S. Impact of temporary closures of emergency departments during the COVID-19 outbreak on clinical outcomes for emergency patients in a metropolitan area. Am J Emerg Med. 2021; 47:35–41. PMID: 33756131.

5. Lee SH, Mun YH, Ryoo HW, Jin SC, Kim JH, Ahn JY, et al. Delays in the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke during the COVID-19 outbreak period: a multicenter study in Daegu, Korea. Emerg Med Int. 2021; 2021:6687765. PMID: 33833878.

6. Kim YJ, Choe JY, Kwon KT, Hwang S, Choi GS, Sohn JH, et al. How to keep patients and staff safe from accidental SARS-CoV-2 exposure in the emergency room: lessons from South Korea’s explosive COVID-19 outbreak. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021; 42(1):18–24. PMID: 32729441.

7. Jaehn P, Holmberg C, Uhlenbrock G, Pohl A, Finkenzeller T, Pawlik MT, et al. Differential trends of admissions in accident and emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. BMC Emerg Med. 2021; 21(1):42. PMID: 33823795.

8. Primessnig U, Pieske BM, Sherif M. Increased mortality and worse cardiac outcome of acute myocardial infarction during the early COVID-19 pandemic. ESC Heart Fail. 2021; 8(1):333–343. PMID: 33283476.

9. Wu J, Mamas M, Rashid M, Weston C, Hains J, Luescher T, et al. Patient response, treatments, and mortality for acute myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2021; 7(3):238–246. PMID: 32730620.

10. Simonsen CZ, Blauenfeldt RA, Hedegaard JN, Kruuse C, Gaist D, Wienecke T, et al. COVID-19 did not result in increased hospitalization for stroke and transient ischemic attack: a nationwide study. Eur J Neurol. 2022; 29(8):2269–2274. PMID: 35397183.

11. Grunau B, Helmer J, Lee S, Acker J, Deakin J, Armour R, et al. Decrease in emergency medical services utilization during early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in British Columbia. CJEM. 2021; 23(2):237–241. PMID: 33709367.

12. Sharma R, Kuohn LR, Weinberger DM, Warren JL, Sansing LH, Jasne A, et al. Excess cerebrovascular mortality in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stroke. 2021; 52(2):563–572. PMID: 33430638.

13. National Medical Center. The Factors of ER Overcrowding and Emergency Transfer Rate by the Ratio of Severe Emergency Patients (NMC2015-PR-04). Seoul, Korea: National Medical Center;2016.

14. Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korean National Emergency Center. National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS). Seoul, Korea: Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare and Korean National Emergency Medical Center;2022.

15. Wu J, Mamas MA, Mohamed MO, Kwok CS, Roebuck C, Humberstone B, et al. Place and causes of acute cardiovascular mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heart. 2021; 107(2):113–119. PMID: 32988988.

16. Yeh CC, Chien CY, Lee TY, Liu CH. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits of patients with an emergent or urgent diagnosis. Int J Gen Med. 2022; 15:4657–4664. PMID: 35548587.

Table 1

General characteristics of patientsa who attended emergency departments of regional and local emergency medical centers before (2019) and during (2020) the COVID-19 era

Values are presented as number (%).

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, ED = emergency department, OPD = outpatient department, KTAS = Korean Triage and Acuity Scale, AMI = acute myocardial infarction

aPatients with three major emergency diseases included those with acute myocardial infarction, stroke, or severe trauma.

Table 2

aOR of patients with three major emergency diseasesa for mortality in emergency departments during the COVID-19 outbreak period (2020) relative to before the COVID-19 outbreak period (2019) at regional and local emergency medical centers adjusting covariates by multiple logistic regression

aOR = adjusted odds ratio, COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, CI = confidence interval, ED = emergency department, OPD = outpatient department, KTAS =Korean Triage and Acuity Scale

aPatients with three major emergency diseases included those with acute myocardial infarction, stroke, or severe trauma.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download