INTRODUCTION

Hemophilia A (HA) is an X-linked recessive coagulation disorder caused by a mutation in the factor VIII (FVIII) gene with an incidence of one in 5,000 male live births.

12 HA is classified as severe (FVIII activity < 1%), moderate (FVIII activity 2–5%), or mild (FVIII activity 6–30%), based on the degree of FVIII deficiency.

12 Although patients with mild HA generally bleed only after trauma or surgery, those with severe HA experience frequent spontaneous hemorrhagic episodes without any trauma.

2 The damaging impact of hemarthrosis, the hallmark of hemophilia, on the life of patients is well established.

3 Hemophilic arthropathy is a serious complication from repeated hemarthrosis, commonly called a “target joint,” and ultimately results in joint deformity and disability.

4 Further, intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is the main cause of mortality and morbidity in patients with hemophilia.

5 ICH occurs spontaneously or following trauma and can result in various sequelae including developmental delay, epilepsy, or cerebral palsy.

5

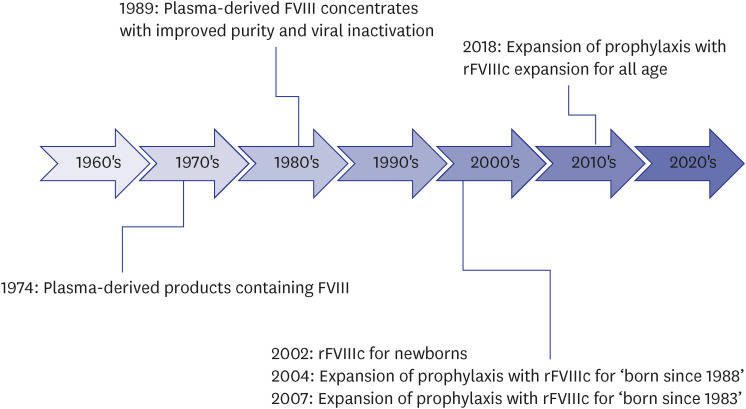

Modern treatment of hemophilia started in the 1970s and was based on human plasma-derived FVIII concentrates (pdFVIIIc).

3 The availability of FVIII replacement therapy has significantly improved the life span and quality of life (QoL) of patients with hemophilia.

36 However, prior to the use of virus inactivation procedures in pdFVIIIc, patients with hemophilia had a high risk of infection with blood-borne viruses such as hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

2 The aforementioned viral infections are associated with the morbidity and mortality of patients with hemophilia because they can cause chronic hepatitis or malignant neoplasm.

7 These serious complications have been reduced following the development of virus inactivation techniques and use of recombinant FVIII concentrates (rFVIIIc) in patients with HA.

8 Further, early prophylaxis with coagulation factor during childhood, before developing repeated hemarthrosis, resulted in protection of the joint compared to delayed prophylaxis or on-demand therapy.

910

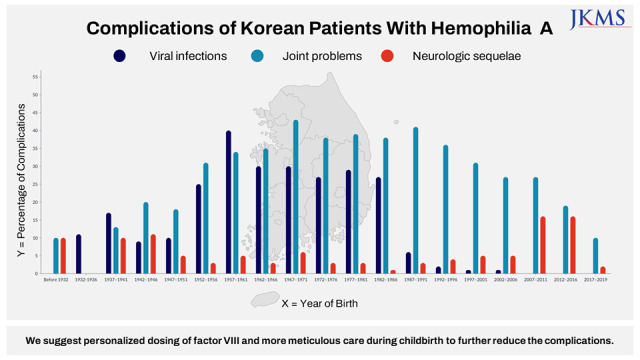

In Korea, there was no effective treatment for HA before the 1970s.

11 The production of low-purity plasma-derived products enriched with FVIII started in 1974.

1112 However, these plasma products were only used for severe bleeding episodes or emergent surgery.

11 Thus, the mortality rate of Korean patients with HA in the 1970s was very high; the average life span was < 30 years.

11 Further, these plasma products were in limited production and had a risk of spreading various viral diseases including HBV or HCV.

11 Since the 1980s, these low-purity products have been replaced by pdFVIIIc with improved purity and viral inactivation.

12 Since 1989, pdFVIIIc with inactivated viruses using the solvent/detergent method (Octa-B

®; Green Cross, Yongin, Korea), has been produced and used domestically.

13 Since the method had no inactivating effect on hepatitis A virus or Parvovirus B19 (these do not have lipid membranes), a high-purity pdFVIIIc (GreenMono

®; Green Cross) was manufactured with the use of monoclonal antibodies; it is still in use.

14 Further, rFVIIIc was first launched in 2002 for Korean newborns with HA. The prophylactic use of rFVIIIc was initially expanded for pediatric patients and then for patients of all age groups in 2018. The history of the management of HA in Korea is shown in

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1

History of the development of management for Korean hemophilia A.

FVIII = factor VIII, rFVIIIc = recombinant factor VIII concentrate.

In other words, before 1989, Korean patients with HA were only able to use plasma-derived products with a high risk of viral infection, and before 2002, they could not receive adequate prophylaxis with rFVIIIc. In recent years, non-factor products, including emicizumab, have been applied to hemophilia patients with excellent outcomes.

15 In Korea, the FVIII concentrate is mainly used in managing patients with HA without inhibitors because of the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) and the opinions of Korean experts.

16 Considering the history of the management of HA in Korea, we can expect that older patients with HA who received pdFVIIIc, mainly on-demand therapy, are more likely to have complications. Further, newly diagnosed neonates or infants with HA who will receive non-factor agents in the future are expected to have different distribution of complications compared to older patients. However, there are no baseline data regarding the frequency of complications in Korean patients with HA.

In the Republic of Korea, the NHIS is available for all citizens. According to Korean law, all citizens are enrolled in the NHIS regardless of individual preference. In particular, HA is classified as a ‘rare and incurable disease’ in Korea; therefore, when registering a disease code for HA, the patient only pays 10% of the treatment cost. In addition, owing to the ‘out-of-pocket limit,’ patients with HA will receive a refund for the amount in excess of the ‘out-of-pocket limit.’ Thus, virtually the costs of the FVIII concentrate for HA patients are borne by the country. The data of all Korean patients with HA are enrolled into the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) database.

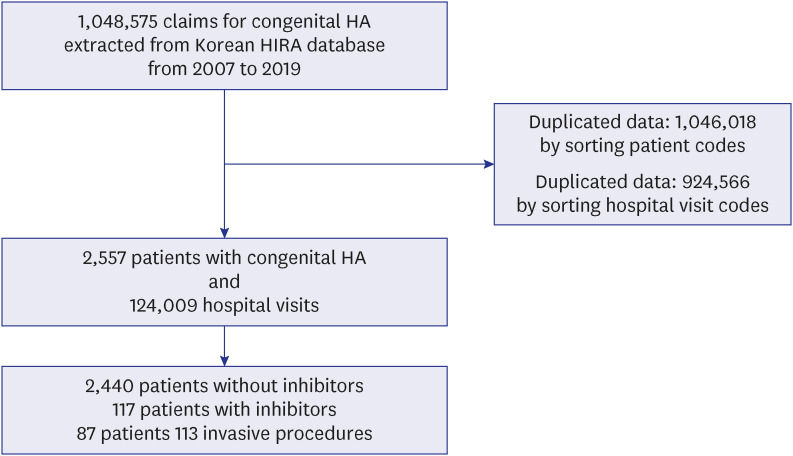

However, additional costs are incurred when surgeries or procedures are performed on the patients due to the complications related to HA. Thus, in this study, we investigated the incidence of complications before and after 1989 or 2002 in patients with HA using the Korean HIRA database. We also investigated the surgeries or procedures resulting from HA complications and the medical costs associated with them.

DISCUSSION

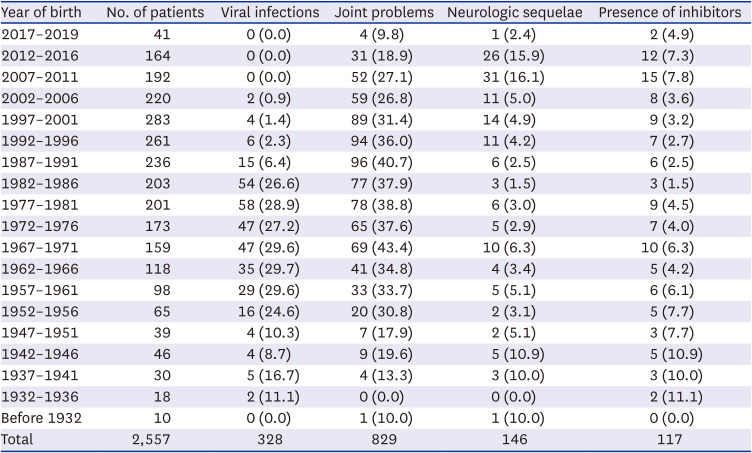

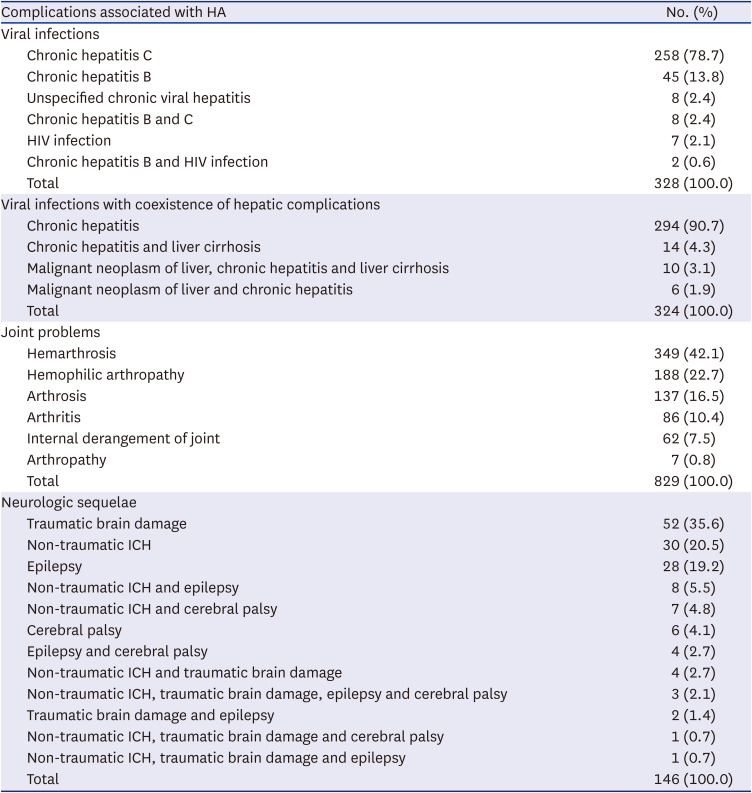

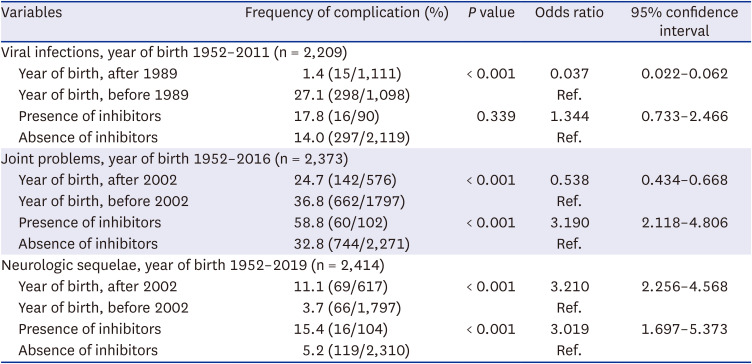

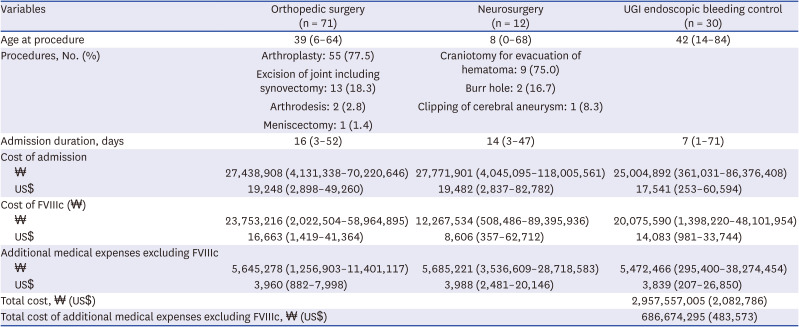

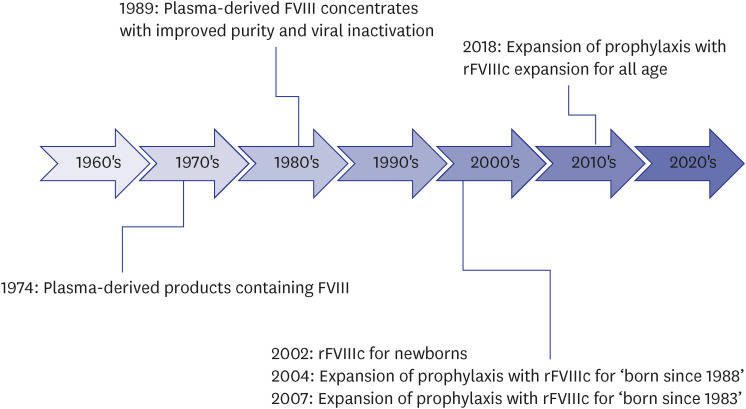

In this study, we analyzed the data of complications experienced by Korean patients with HA from 2007 to 2019 using the HIRA database. Among the 2,557 patients, approximately half (42.4%) had one or more complications. Because the pdFVIIIc with inactivated viruses was first developed in 1989 and the rFVIIIc was first used in 2002 with subsequent expanded prophylactic use in Korea, the prevalence of complications was compared between patients born before and after 1989 or 2002. Considering the median life expectancy of Korean patients with HA, the analysis was performed for the patients who were born after 1952. Considering the age of developing viral infections and first hemarthrosis in patients with HA, the children born after 2012 were excluded from the analysis of viral infections, and the children born after 2017 were excluded from the analysis for joint problems. Because the presence of inhibitors is also an important factor related to the prevalence of complications, we analyzed the rate of complications according to the presence of an inhibitor. As a result, the incidence of viral infections was lower in patients born after 1989, and the incidence of joint problems was lower in patients born after 2002. However, the incidence of neurologic sequelae was higher in patients born after 2002. Regarding inhibitors, patients with inhibitors had more joint problems and neurologic sequelae than those without inhibitors. There was no difference in viral infections between patients with and without inhibitors.

In terms of the QoL of patients with hemophilia, HCV or HIV infection and joint limitations were associated with a decreased QoL in the domains of general health and vitality.

21 Further, hemorrhagic events, infection with HCV or HIV, or having hepatic disease were the leading causes of death in patients with HA.

7 In a systematic literature review from 2010 to 2020, patients with HA had a higher mortality risk than the general population.

7 Considering these international results, we can expect that newly diagnosed Korean patients with HA will have an improved QoL and a decreased mortality risk with the development of therapeutic drugs. In the current study, Korean patients with HA born after 1989 showed a dramatically lower incidence of viral infections than those born before 1989. The study also found that patients born after 2002 had fewer joint problems. However, the degree of reduction of joint problems was lower than we expected, probably because the use of prophylaxis was not very common among all patients with HA under the Korean NHIS; it took over 10 years for the prophylactic use of FVIII concentrates to become widespread as shown in

Fig. 1.

The occurrence of neurologic sequelae, a significant complication, did not decrease after the introduction of rFVIIIc and prophylaxis in this study in Korea. Similar to the current findings, it has been reported that ICH occurs mainly in neonates and older patients with hemophilia.

22 ICH is a major cause of mortality in patients with hemophilia, and its morbidity is considerable in surviving pediatric patients resulting in psycho-intellectual sequelae and neurological impairment.

23 According to a previous Korean cohort study from 1991 to 2012, the median life expectancy of male patients with HA is 69 years, which is 8 years less than the general male population of South Korea (77 years in 2010).

12 Moreover, the most common causes of death in Korean patients with HA were ICH and cancer.

12 In other words, the occurrence of ICH may impair the life expectancy of patients with hemophilia and impact their long-term prognosis.

It is known that 3.5–4.0% of neonates with hemophilia experience ICH, which is much higher (40–80 times) than that in the normal population, even with good standards of health care.

24 In this study, the prevalence of neurologic sequelae was 2.4% in patients born in 2017–2019 and 15.9% in patients born in 2012–2016 (

Table 1). These sequelae do not include only ICH, but also epilepsy or cerebral palsy, the results of ICH. The rate of neurologic sequelae in the overall patients was 5.7% (146/2,557), and 4.2% (108/2,557) patients had traumatic brain damage or non-traumatic ICH (

Table 2). In general, the ICH mortality in patients with hemophilia has decreased; however, it is still reported to be approximately 20%.

5 Overall, neurologic complications (seizure, developmental delay, or motor function problems), including deaths, occur in 50–60% of children with ICH.

25 In other countries, the incidence of ICH in patients with hemophilia has decreased through the use of prophylaxis.

25 Pediatric patients with hemophilia undergoing regular and frequent prophylaxis have a low risk of ICH compared with those who do not undergo regular prophylaxis.

25

These findings suggest that ICH is an important problem related to hemophilia in Korea that occurs among all ages and requires adequate preventive strategies. Younger patients with HA have shorter FVIII half-lives than older patients.

26 Thus, younger children may need a higher dose of FVIII to sustain a desired trough level of FVIII than adults.

26 However, in Korea, the dose and frequency of coagulation factors that may be prescribed for hemophilia by physicians are strictly limited due to NHIS issues. An additional dose of coagulation factor products may only be prescribed on recommendation from a physician when bleeding persists. Therefore, personalized prophylaxis according to the individual pharmacokinetics is difficult to implement in Korean patients with hemophilia.

Furthermore, when female Korean hemophilia carriers become pregnant, they often do not anticipate and prevent ICH during childbirth for a child with hemophilia. This is because genetic diagnosis and counselling for hemophilia are not yet common in Korea. ICH can occur regardless of the mode of delivery or the severity of hemophilia.

27 Thus, women with postpartum hemorrhage should undergo a thorough hematologic work-up, and early screening is necessary for all infants with suspected hemophilia.

27 We suggest that the problem of a higher percentage of neurologic sequelae in Korean patients with HA born after 2002 will be reduced by personalized FVIII dosing according to individual pharmacokinetics, the application of extended-half-life factor products

8 or non-factor products,

15 and more meticulous care during childbirth for female carriers.

There are some limitations to this study considering the nature of the Korean HIRA database. First, the severity of HA (severe, moderate, or mild phenotypes) was not known. Second, the presence of a “target joint” was difficult to identify. Third, viral infections without ICD-10 codes are difficult to identify. In order to solve these limitations, additional chart reviews that can supplement the Korean HIRA database are needed in the future. Despite of aforementioned limitations, this study showed the objective changes in complication patterns according to the advances in management of HA in Korea for the first time. Moreover, the results of this study can be used as reference data that can be compared with the frequency of complications in Korean patients with HA whose treatment direction will be changed to non-factor products or gene therapy in the future.

To conclude, the use of pdFVIIIc with inactivated viruses and active prophylaxis using rFVIIIc have reduced the occurrence of viral infections and joint problems in Korean patients with HA. However, the occurrence of neurologic sequelae did not decrease; thus, additional efforts are needed to reduce ICH in patients with HA. We suggest that active prophylaxis, personalized care according to the individual pharmacokinetics, and increased meticulous care during childbirth are needed to further reduce the complications. A subject that requires future research will be the change in the frequency of complications in Korean patients with HA when extended half-life products, novel non-factor products, and gene therapy become popular.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download