1. Yoo JH, Hong ST. The outbreak cases with the novel coronavirus suggest upgraded quarantine and isolation in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(5):e62. PMID:

32030926.

2. Nham E, Song JY, Noh JY, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ. COVID-19 vaccination in Korea: past, present, and the way forward. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(47):e351. PMID:

36472087.

3. Landler M. Vaccine mandates rekindle fierce debate over civil liberties. The New York Times. 2021. 12. 10.

4. Jiang S. Don’t rush to deploy COVID-19 vaccines and drugs without sufficient safety guarantees. Nature. 2020; 579(7799):321. PMID:

32179860.

5. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384(5):403–416. PMID:

33378609.

6. Karlsson LC, Soveri A, Lewandowsky S, Karlsson L, Karlsson H, Nolvi S, et al. Fearing the disease or the vaccine: the case of COVID-19. Pers Individ Dif. 2021; 172:110590. PMID:

33518869.

7. Pertwee E, Simas C, Larson HJ. An epidemic of uncertainty: rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy. Nat Med. 2022; 28(3):456–459. PMID:

35273403.

8. Romer D, Jamieson KH. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc Sci Med. 2020; 263:113356. PMID:

32967786.

9. MacDonald NE. SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015; 33(34):4161–4164. PMID:

25896383.

10. Dubé È, Ward JK, Verger P, MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy, acceptance, and anti-vaccination: trends and future prospects for public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021; 42(1):175–191. PMID:

33798403.

11. Murphy J, Vallières F, Bentall RP, Shevlin M, McBride O, Hartman TK, et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun. 2021; 12(1):29. PMID:

33397962.

12. Hwang SE, Kim WH, Heo J. Socio-demographic, psychological, and experiential predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Korea, October-December 2020. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022; 18(1):1–8.

13. Kreps S, Dasgupta N, Brownstein JS, Hswen Y, Kriner DL. Public attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination: the role of vaccine attributes, incentives, and misinformation. NPJ Vaccines. 2021; 6(1):73. PMID:

33990614.

14. Park HK, Ham JH, Jang DH, Lee JY, Jang WM. Political ideologies, government trust, and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Korea: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(20):10655. PMID:

34682401.

15. Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021; 27(2):225–228. PMID:

33082575.

16. Shakeel CS, Mujeeb AA, Mirza MS, Chaudhry B, Khan SJ. Global COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: a systematic review of associated social and behavioral factors. Vaccines (Basel). 2022; 10(1):110. PMID:

35062771.

17. Kim M, Park IH, Kang YS, Kim H, Jhon M, Kim JW, et al. Comparison of psychosocial distress in areas with different COVID-19 prevalence in Korea. Front Psychiatry. 2020; 11:593105. PMID:

33329143.

18. Lee YR, Lee JY, Park IH, Kim M, Jhon M, Kim JW, et al. The relationships among media usage regarding COVID-19, knowledge about infection, and anxiety: structural model analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(48):e426. PMID:

33316862.

19. Jung HR, Park C, Kim M, Jhon M, Kim JW, Ryu S, et al. Factors associated with mask wearing among psychiatric inpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Schizophr Res. 2021; 228:235–236. PMID:

33476952.

20. Kim SW, Park IH, Kim M, Park AL, Jhon M, Kim JW, et al. Risk and protective factors of depression in the general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in Korea. BMC Psychiatry. 2021; 21(1):445. PMID:

34496823.

21. Lee JY, Kim M, Jhon M, Kim JW, Ryu S, Kim JM, et al. Factors associated with a negative emotional response to news media and nationwide emergency text alerts during the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2021; 18(9):825–830.

22. Ryu S, Park IH, Kim M, Lee YR, Lee J, Kim H, et al. Network study of responses to unusualness and psychological stress during the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. PLoS One. 2021; 16(2):e0246894. PMID:

33635935.

23. Jang H, Park AL, Lee YR, Ryu S, Lee JY, Kim JM, et al. Relationship between economic loss and anxiety during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: moderating effects of knowledge, gratitude, and perceived stress. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 13:904449. PMID:

35770062.

24. Lee YR, Chung YC, Kim JJ, Kang SH, Lee BJ, Lee SH, et al. Effects of COVID-19-related stress and fear on depression in schizophrenia patients and the general population. Schizophrenia (Heidelb). 2022; 8(1):15. PMID:

35249110.

26. Park SJ, Choi HR, Choi JH, Kim KW, Hong JP. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Anxiety Mood. 2010; 6(2):119–124.

27. Lee SH, Shin C, Kim H, Jeon SW, Yoon HK, Ko YH, et al. Validation of the Korean version of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 self-rating scale. Asia-Pac Psychiatry. 2022; 14(1):e12421. PMID:

32893471.

28. Mccullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002; 82(1):112–127. PMID:

11811629.

29. Kwon SJ, Kim KH, Lee HS. Validation of the Korean version of gratitude questionnaire. Korean J Health Psychol. 2006; 11(1):177–190.

30. Rammstedt B, John OP. Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. J Res Pers. 2007; 41(1):203–212.

31. Kim SY, Kim JM, Yoo JA, Bae KY, Kim SW, Yang SJ, et al. Standardization and validation of big five inventory-Korean version (BFI-K) in elders. Korean J Biol Psychiatry. 2010; 17(1):15–25.

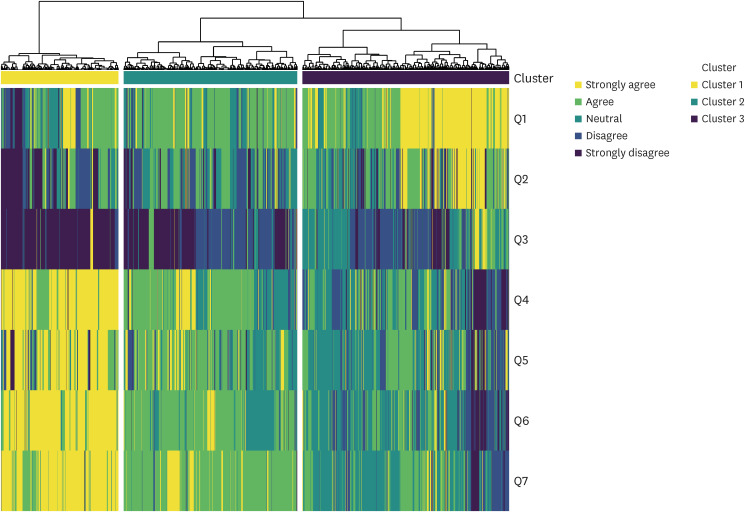

32. Bolin JH, Edwards JM, Finch WH, Cassady JC. Applications of cluster analysis to the creation of perfectionism profiles: a comparison of two clustering approaches. Front Psychol. 2014; 5:343. PMID:

24795683.

33. Murtagh F, Contreras P. Algorithms for hierarchical clustering: an overview. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Data Min Knowl Discov. 2012; 2(1):86–97.

34. Felten R, Dubois M, Ugarte-Gil MF, Chaudier A, Kawka L, Bergier H, et al. Cluster analysis reveals three main patterns of beliefs and intention with respect to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021; 60(SI):SI68–SI76. PMID:

33983432.

35. Sallam M, Al-Sanafi M, Sallam M. A global map of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates per country: an updated concise narrative review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022; 15:21–45. PMID:

35046661.

36. Reiter PL, Pennell ML, Katz ML. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 2020; 38(42):6500–6507. PMID:

32863069.

37. Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine : a survey of U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020; 173(12):964–973. PMID:

32886525.

38. Robertson E, Reeve KS, Niedzwiedz CL, Moore J, Blake M, Green M, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain Behav Immun. 2021; 94:41–50. PMID:

33713824.

39. Al-Hanawi MK, Alshareef N, El-Sokkary RH. Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination among older adults in Saudi Arabia: a community-based survey. Vaccines (Basel). 2021; 9(11):1257. PMID:

34835188.

40. Zintel S, Flock C, Arbogast AL, Forster A, von Wagner C, Sieverding M. Gender differences in the intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2022.

41. Sprengholz P, Korn L, Eitze S, Felgendreff L, Siegers R, Goldhahn L, et al. Attitude toward a mandatory COVID-19 vaccination policy and its determinants: evidence from serial cross-sectional surveys conducted throughout the pandemic in Germany. Vaccine. 2022; 40(51):7370–7377. PMID:

35153092.

42. Leuchter RK, Jackson NJ, Mafi JN, Sarkisian CA. Association between Covid-19 vaccination and influenza vaccination rates. N Engl J Med. 2022; 386(26):2531–2532. PMID:

35704429.

43. Sharma B, Racey CS, Booth A, Albert A, Smith LW, Gottschlich A, et al. Characterizing intentions to receive the COVID-19 vaccine among the general population in British Columbia based on their future intentions towards the seasonal influenza vaccine. Vaccine X. 2022; 12:100208. PMID:

35996447.

44. Kumar S, Shah Z, Garfield S. Causes of vaccine hesitancy in adults for the influenza and COVID-19 vaccines: a systematic literature review. Vaccines (Basel). 2022; 10(9):1518. PMID:

36146596.

45. Klüver H, Hartmann F, Humphreys M, Geissler F, Giesecke J. Incentives can spur COVID-19 vaccination uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021; 118(36):e2109543118. PMID:

34413212.

46. Tan M, Straughan PT, Cheong G. Information trust and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy amongst middle-aged and older adults in Singapore: a latent class analysis Approach. Soc Sci Med. 2022; 296:114767. PMID:

35144226.

47. Wilson SL, Wiysonge C. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Glob Health. 2020; 5(10):e004206.

48. Lee SK, Sun J, Jang S, Connelly S. Misinformation of COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy. Sci Rep. 2022; 12(1):13681. PMID:

35953500.

49. Sekizawa Y, Hashimoto S, Denda K, Ochi S, So M. Association between COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and generalized trust, depression, generalized anxiety, and fear of COVID-19. BMC Public Health. 2022; 22(1):126. PMID:

35042506.

50. Koltai J, Raifman J, Bor J, McKee M, Stuckler D. COVID-19 vaccination and mental health: a difference-in-difference analysis of the understanding America study. Am J Prev Med. 2022; 62(5):679–687. PMID:

35012830.

51. Wood AM, Froh JJ, Geraghty AW. Gratitude and well-being: a review and theoretical integration. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010; 30(7):890–905. PMID:

20451313.

52. Kumar SA, Edwards ME, Grandgenett HM, Scherer LL, DiLillo D, Jaffe AE. Does gratitude promote resilience during a pandemic? An examination of mental health and positivity at the onset of COVID-19. J Happiness Stud. 2022; 23(7):3463–3483. PMID:

35855779.

53. Jans-Beken L. A perspective on mature gratitude as a way of coping with COVID-19. Front Psychol. 2021; 12:632911. PMID:

33828504.

54. Lee JY, Kim M, Jhon M, Kim H, Kang HJ, Ryu S, et al. The association of gratitude with perceived stress among nurses in Korea during COVID-19 outbreak. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2021; 35(6):647–652. PMID:

34861959.

55. Karns CM, Moore WE 3rd, Mayr U. The cultivation of pure altruism via gratitude: a functional MRI study of change with gratitude practice. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017; 11:599. PMID:

29375336.

56. Wilt J, Revelle W. Extraversion. Leary MR, Hoyle RH, editors. Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press;2009. p. 27–45.

57. Graziano WG, Tobin RM. Agreeableness. Leary MR, Hoyle RH, editors. Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press;2009. p. 46–61.

58. Roberts BW, Jackson JJ, Fayard JV, Edmonds G, Meints J. Conscientiousness. Leary MR, Hoyle RH, editors. Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press;2009. p. 369–381. .

59. Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 2009; 64(4):241–256. PMID:

19449983.

60. Lin FY, Wang CH. Personality and individual attitudes toward vaccination: a nationally representative survey in the United States. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):1759. PMID:

33228661.

61. Halstead IN, McKay RT, Lewis GJ. COVID-19 and seasonal flu vaccination hesitancy: Links to personality and general intelligence in a large, UK cohort. Vaccine. 2022; 40(32):4488–4495. PMID:

35710507.

62. Howard MC. The good, the bad, and the neutral: vaccine hesitancy mediates the relations of Psychological Capital, the Dark Triad, and the Big Five with vaccination willingness and behaviors. Pers Individ Dif. 2022; 190:111523. PMID:

35079191.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download