INTRODUCTION

Vertebral compression fracture is the most common fragility fracture and its incidence is increasing worldwide.

1 These fractures cause persistent pain and deterioration in the quality of daily life, and increase medical expenditures, causing pain and increasing social and economic burdens.

23 Although vertebral compression fractures can result from osteoporosis caused by old age or menopause, they can also be triggered by secondary osteoporosis caused by chronic disease or medications.

45 Considering the serious public health burden, investigation of vertebral compression fractures induced by chronic disease or medications is important.

5

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic relapsing inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract.

6 Chronic intestinal inflammation causes malabsorption, leading to deficiencies in iron, zinc, calcium, and vitamin D.

7 Moreover, the medications used to treat IBD, such as corticosteroids and immunomodulators, can adversely affect bone metabolism.

8 In addition, the aging of the IBD population and the increased disease duration may affect the risk of comorbidities such as vertebral fractures.

9

There is a correlation between IBD and the risk of vertebral compression fractures.

101112 The risk of vertebral fractures is increased in IBD patients, particularly in CD patients, and risk factors include age, sex, corticosteroids, and comorbidities.

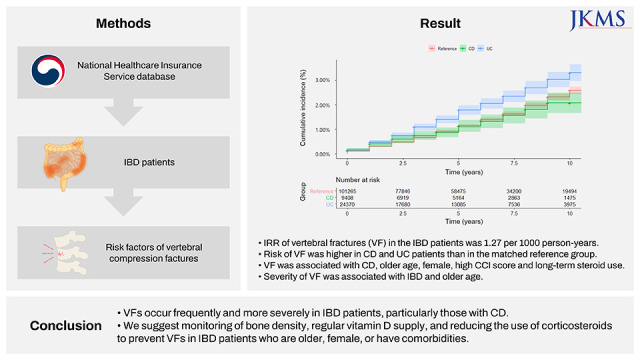

10111213 However, whether the severity of vertebral compression fractures differs between the IBD patients and healthy controls, or between CD and UC groups, was unclear. We investigated risk factors and the severity of vertebral compression fractures in IBD patients using the National Healthcare Insurance Service (NHIS) database of South Korea.

Go to :

METHODS

Data source

The NHIS database was used for this population-based cohort study. We used the diagnostic codes of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) code and the V code in the rare intractable diseases (RID) database. RID registration in South Korea requires clinical, endoscopic, and pathologic findings diagnostic of IBD.

Study population

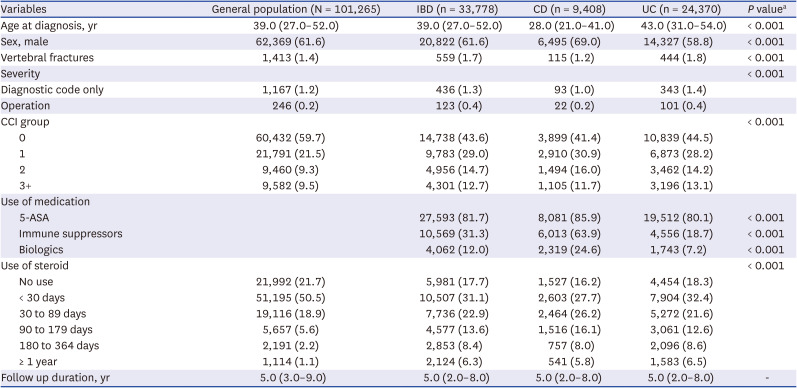

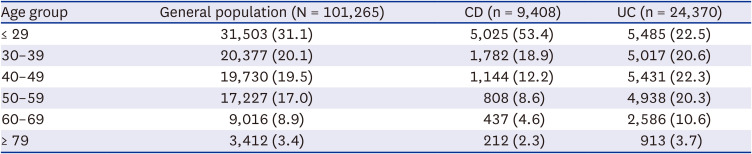

IBD patients were defined as those diagnosed with ICD-10 and RID registration system (V code). CD patients were defined as those with ICD-10 code K50 and V code V130 and UC patients as ICD-10 code K51 and V code V131. After a washout period of 1 year (2007), 34,158 patients with IBD aged 18–79 years were included between 2008 and 2018. We excluded patients with a history of vertebral fractures before the index date. The sex- and 10-year age matched non-IBD reference population was selected from the NHIS database during the same study period at a matching ratio of 1:3.

Outcomes

Demographic features (age, sex), comorbidities, and use of UC medications were analyzed. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to assess the severity of underlying comorbidities. Based on the index date, the CCI was calculated by observing comorbidities over the past year and assigned weighted scores of 0, 1, 2, and ≥ 3. We collected data on IBD medications, including 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), immunomodulators (azathioprine, mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and methotrexate), steroids, and biologics (infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, vedolizumab).

Vertebral fractures were defined as ICD-10 codes M48.4, M48.5, M49.5, M80.88, S22.0, S22.1, S32.0, S32.7 and T08.x and procedure codes as N0471, N0472, N0473, N0474, and N0630. Vertebral compression fractures are treated conservatively—bed rest, analgesics, brace, and physical therapy.

9 However, in severe cases such as kyphosis due to excessive vertebral compression or intractable pain, vertebral augmentation such as vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty can be used.

9 Therefore, patients who have undergone procedures such as vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty for vertebral compression fractures have a greater fracture severity than those treated conservatively. We defined the patients who underwent vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty after being diagnosed with a vertebral fracture, cases with both a diagnosis code and a procedure code, as having a severe vertebral fracture than the patients with only diagnosis codes. When extracting data, we included the patients with vertebral fractures that occurred after the diagnosis of IBD and clarified the precedent relationship between IBD, vertebral fractures, and procedures performed for treatment after vertebral fractures occurred.

Statistical analysis

We performed a descriptive statistical analysis of the patients’ characteristics. The χ2 test was used for binary or categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. We assessed the cumulative vertebral fracture incidence between IBD patients and the general population and performed Cox regression analyses to determine whether the duration of steroid use was associated with the occurrence and severity of vertebral fractures in IBD patients and the general population. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SAS version 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Eunpyeong St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea (IRB approval number PC19ZNSE0128, November 7, 2019). No informed consent was required from patients due to the nature of public data from NHIS.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

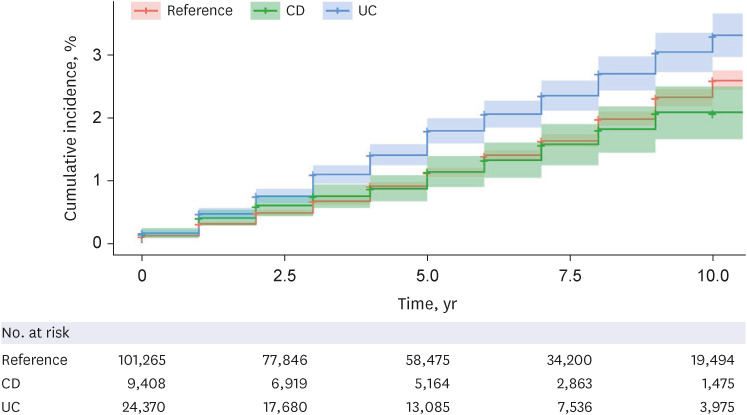

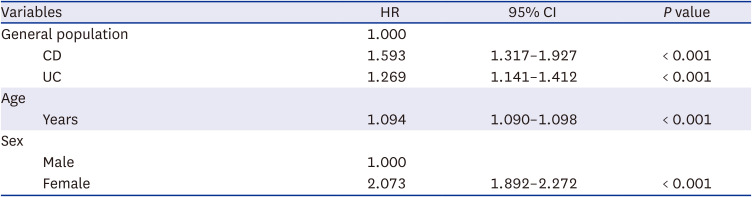

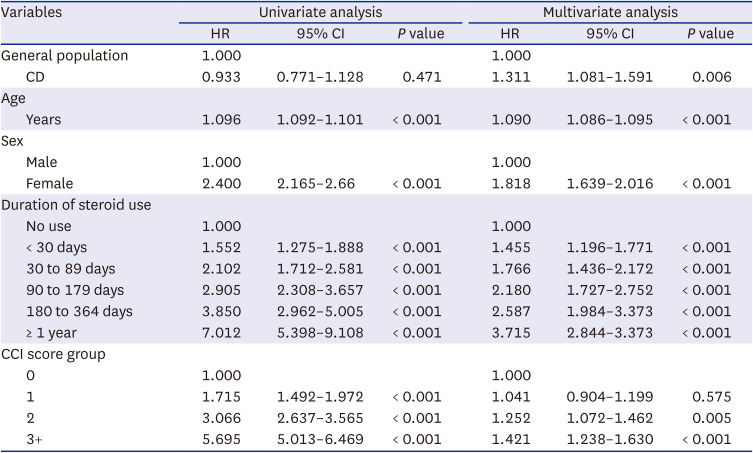

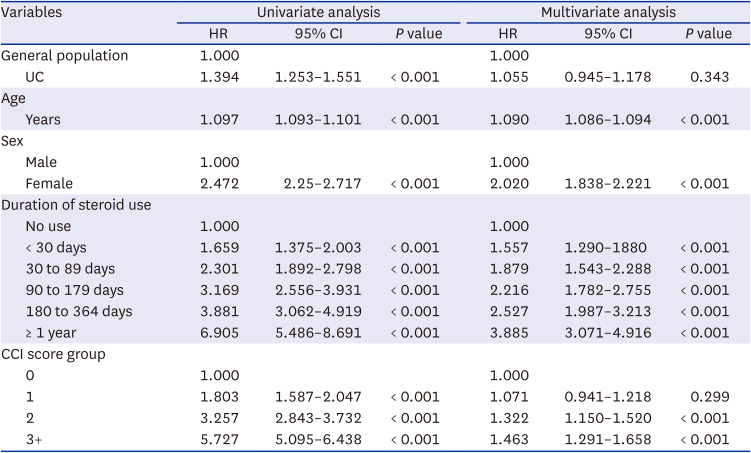

The risk for vertebral compression fractures was significantly higher in IBD patients than in the reference population. The risk of vertebral fracture in CD patients was higher than in UC patients (

Table 2). We evaluated the risk of vertebral fracture in Asian patients with IBD; the results are consistent with previous large cohort studies of Western populations in which the risks of hip and any fractures were higher in IBD patients.

111214 A recent study of the risk of vertebral and hip fractures in Asian populations yielded similar results.

10 The risk of vertebral and hip fractures was higher in IBD patients (IRR, 1.24) compared with a matched reference group.

10 However, previous studies have evaluated the risk of vertebral fractures and pelvic fractures without distinguishing between UC and CD patients.

101112 In this study, to increase accuracy, we evaluated the risk of only vertebral fractures.

Risk factors for vertebral fractures in IBD patients were old age, female sex, and steroid use, similar to previous reports.

1012 The risk of vertebral fracture was higher in CD patients than in UC patients in a multivariate analysis. This is similar to previous reports that hip fractures and any fractures occur more frequently in CD patients.

101112 In a large-scale study of 2,102 patients with IBD conducted in the United Kingdom, patients with CD had a higher risk of spine fractures than those with UC.

11 In a population-based study of 83,435 patients with IBD conducted in Sweden, the relative risks of hip fracture were 1.7 for CD patients and 1.3 for UC patients, and those of any fracture were 1.2 for CD patients and 1.2 for UC patients.

12 A recent population-based study of 18,228 patients with IBD from South Korea reported that among patients < 60 years of age at diagnosis of IBD, the IRR of fractures in CD and UC patients was 1.15 and 0.96, respectively. Among patients > 60 years of age at diagnosis of IBD, the IRR of fractures in CD and UC patients was 2.19, and 1.32 respectively.

10 Although the cause of the difference in fracture risk between CD and UC patients is unclear, it might be a result of differences in time of disease onset, location, and/or severity; inflammatory activity; and inflammatory mediator levels.

815

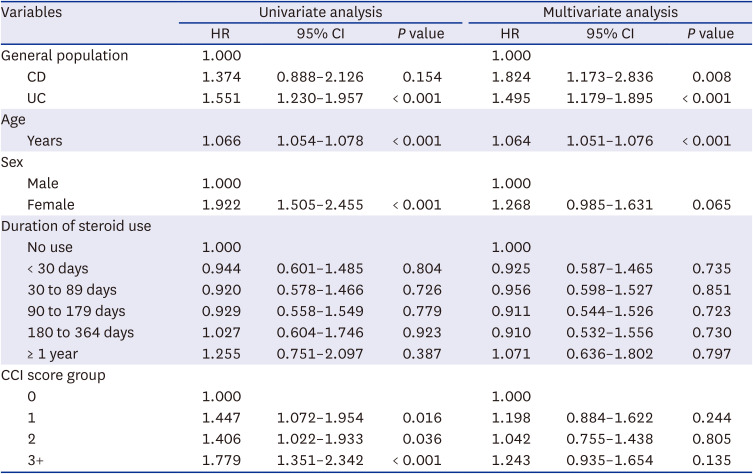

Compared with the matched reference population, severe vertebral fractures that required vertebral augmentation procedures such as vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty were more frequent in IBD patients. Other risk factors for severe vertebral fractures were older age and female sex. Interestingly, among IBD patients, the risk of severe vertebral fractures was higher in UC patients (HR, 1.551) than in CD patients (HR, 1.374) in a univariate analysis. This result might be because, compared with CD patients, UC patients were more numerous, had an older mean age, and a larger proportion of females. However, in multivariate analysis, the risk of severe vertebral fractures was higher in CD patients (HR, 1.824) than in UC patients (HR, 1.495). This is likely to be a result of greater disease activity and malabsorption of nutrients in CD compared to UC, increasing the risk of osteoporosis and severe vertebral fractures.

7813 These results are consistent with a previous population-based study in which patients with CD had a higher risk of osteoporosis.

16 Therefore, to prevent severe vertebral fractures in CD patients, more attention should be paid to CD treatment.

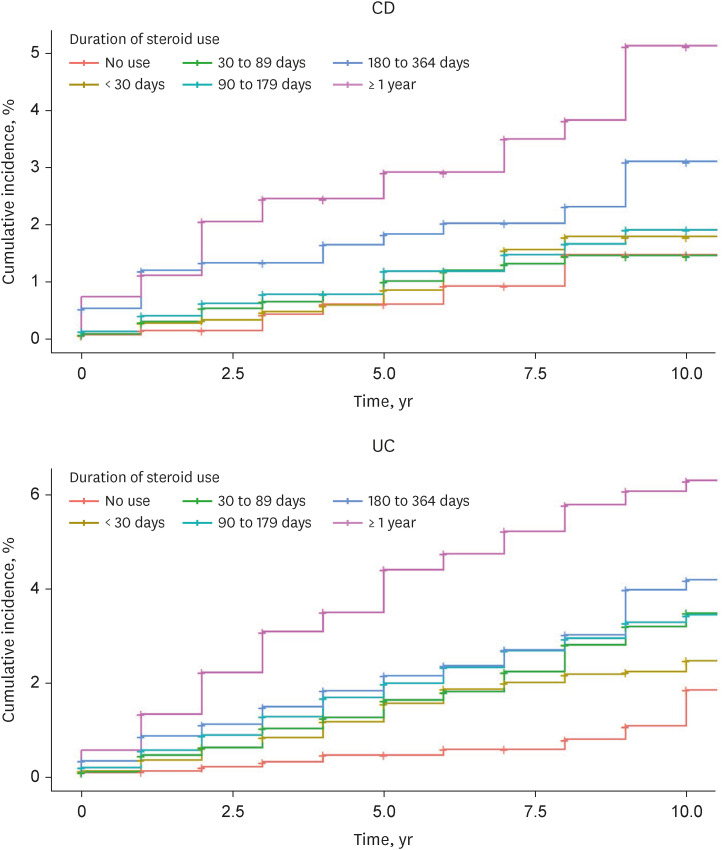

Use of corticosteroids causes secondary osteoporosis and increases the risk of fractures.

1718 In a recent meta-analysis of 470,541 IBD patients, those with fractures were more likely to be on corticosteroids than those without fractures (odds ratio, 1.47).

19 Several large-scale studies have reported that the cumulative dose of corticosteroids increases the risk of fractures in IBD patients.

111214 In this study, long-term steroid use was associated with the occurrence, but not the severity, of vertebral fractures. These findings suggest that long-term steroid use should be avoided to reduce vertebral fractures in IBD patients. In addition, biologics instead of steroids should be considered, especially for IBD patients who are older, female, or have comorbidities.

Interestingly, this study showed the medication-using patterns of the UC and CD groups appear to be different. There are some possible explanations for this finding. Firstly, conventional drugs such as 5-ASA, corticosteroids, and immune modulators should be preceded first according to the guideline of Health Insurance Review and Assessment service (HIRA), which has some differences in the guideline for CD and UC. For CD, immunomodulators are used along with 5-ASA and steroids. For UC, 5-ASA is used as a base and steroids are recommended as an adjunctive therapy, and also the role of immunomodulators is less important than in CD. Secondly, HIRA allows the use of biologics for patients with moderate-to-severe IBD who are not responsive to, intolerant of, or contraindicated to conventional drugs. All Korean physicians follow this policy, which is why the majority of patients have used 5-ASA. CD has a higher proportion of moderate-severe cases than UC, so it is estimated that there will be more use of biological agents.

There were limitations in our study. First, since this study was a big data study using The NHIS database, we could not differentiate refractures that occurred after diagnosis of IBD. We targeted the first vertebral fracture after diagnosis of IBD. Old vertebral fractures occurring prior to diagnosis of IBD were excluded. Second, there was no information on bone mineral density in this study. Considering that bone mineral density has a strong relationship with the risk of vertebral fractures, the lack of data on bone mineral density may be an inevitable limitation of big data research. Third, we were unable to collect data on the activity or location/extent of IBD from this limited database. Fourth, data on anemia, hypertension, diabetes, osteoporosis, and other metabolic diseases that may affect the patient’s disease and vertebral fracture were limited and could not be analyzed. Fifth, we could not analyze chronic diseases that may be present in the reference population. Additionally, because we were unable to stratify the matched reference population according to the status of corticosteroid exposure together with the age- and sex-matching method, the effect of corticosteroid exposure on the risk of fractures may have been lessened. Sixth, the effect of the cumulative steroid dose could not be proven since we set the length of steroid usage, not the cumulative dose, as a factor affecting vertebral fractures. Seventh, we did not analyze the effects of drugs such as 5-ASA, immunomodulators, and biological agents on vertebral fractures. Since it was difficult to see those drugs as the direct cause of osteoporosis-inducing factors, we excluded them from the analysis and focused on the main factor, steroids. Lastly, we used only the vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty codes to determine the severity of vertebral fractures and did not use surgical codes. The reason for not using surgical codes is that in the case of vertebral fracture surgery, the main surgical codes are for instrument fixation, decompression, and fusion. However, the same surgical codes are used for the treatment of other spinal diseases such as spinal stenosis and spondylolisthesis. It is very difficult to distinguish whether the patient has undergone surgery only for a vertebral fracture or for other spinal diseases. Therefore, we only used the vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty codes specific to vertebral fractures and their treatment.

In conclusion, the risk of vertebral fractures and of severe vertebral fractures requiring augmentation procedures was higher in IBD patients, particularly those with CD, than in the general population. Old age, female sex and long-term steroid use were associated with vertebral fractures in IBD patients. Therefore, we suggest frequent monitoring of bone density, regular administration of vitamin D supplements, and reducing the duration of corticosteroid use to prevent vertebral fractures in IBD patients.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download