Abstract

Purpose

Methods

Results

References

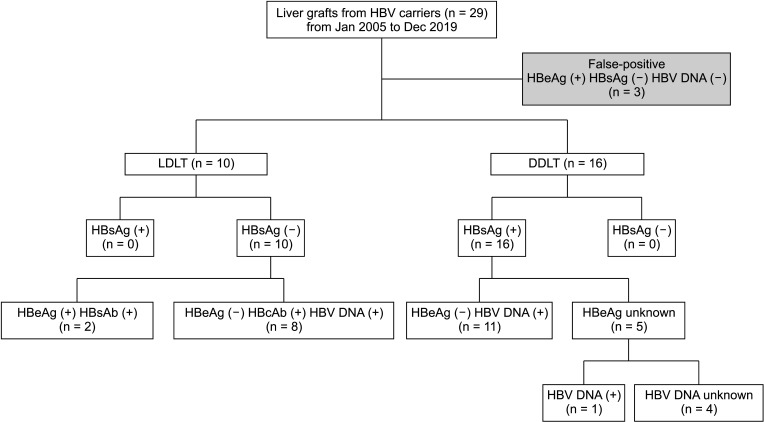

Fig. 1

Flow chart of the study population. Three patients were excluded as their serology results were considered to be false positives following consultation with a hepatologist. Twenty-six donors were regarded as having active (deceased donor liver transplantation, DDLT) or chronic (living donor liver transplantation, LDLT) HBV infection. All deceased donor liver transplantations used HBsAg (+) grafts. All living donors had chronic hepatitis with HBsAg (–) seroconversion. Serum liver enzyme levels were within the normal ranges in all donors.

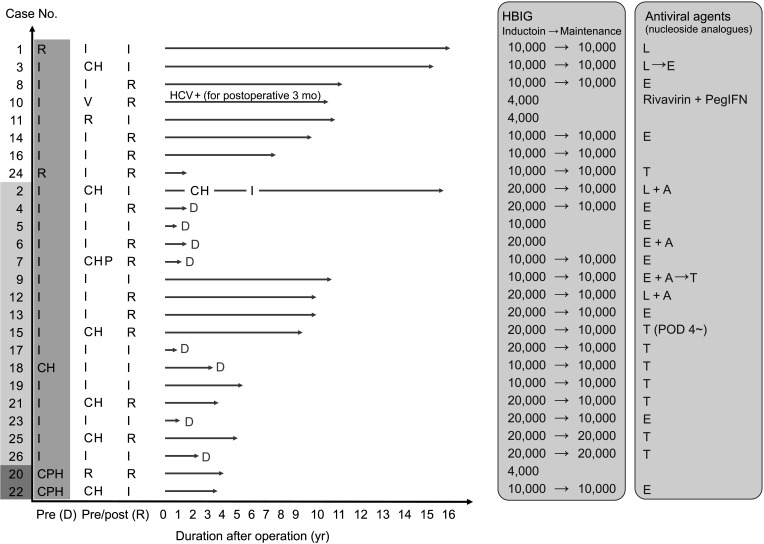

Fig. 2

HBV infection stage of donors and recipients, as well as transplantation outcomes and perioperative management of each patient. Eight donors with HBcAb (+) HBV DNA (+) were regarded as cases of resolving HBV, an immune-inactive stage with low viral replication. The other 2 donors had HBeAg (+) chronic HBV infection with HBsAg seroconversion. D is marked at the end of the arrow of deceased recipients. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) was administered as a maintenance dose after induction. The operator decided the dose based on the HBV infection statuses of the donor and recipient. The same principle was applied to dosages of antiviral agents. Pre (D) indicates the HBV infection stage of donors, pre (R) indicates that of recipients before transplantation, and post (R) indicates that of recipients after transplantation. R, resolution; I, inactive; CH, HBeAg (–) chronic hepatitis; V, vaccinated; CHP, HBeAg (+) chronic hepatitis; CPH, HBe-positive chronic hepatitis with HBV seroconversion; HCV+, HCV DNA positive; L, lamivudine; A, adefovir; E, entecavir; T, tenofovir; PegIFN, pegylated interferon a2a; POD, postoperative day.

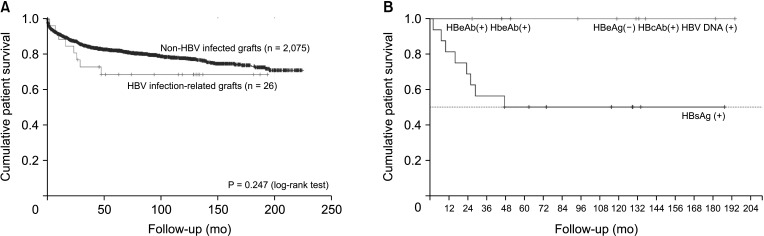

Fig. 3

Kaplan-Meier curve for recipient survival. (A) HBV infection status of the donor did not affect recipient survival (P = 0.247, log-rank test). (B) All reported deaths occurred in patients who received HbsAg (+) grafts.

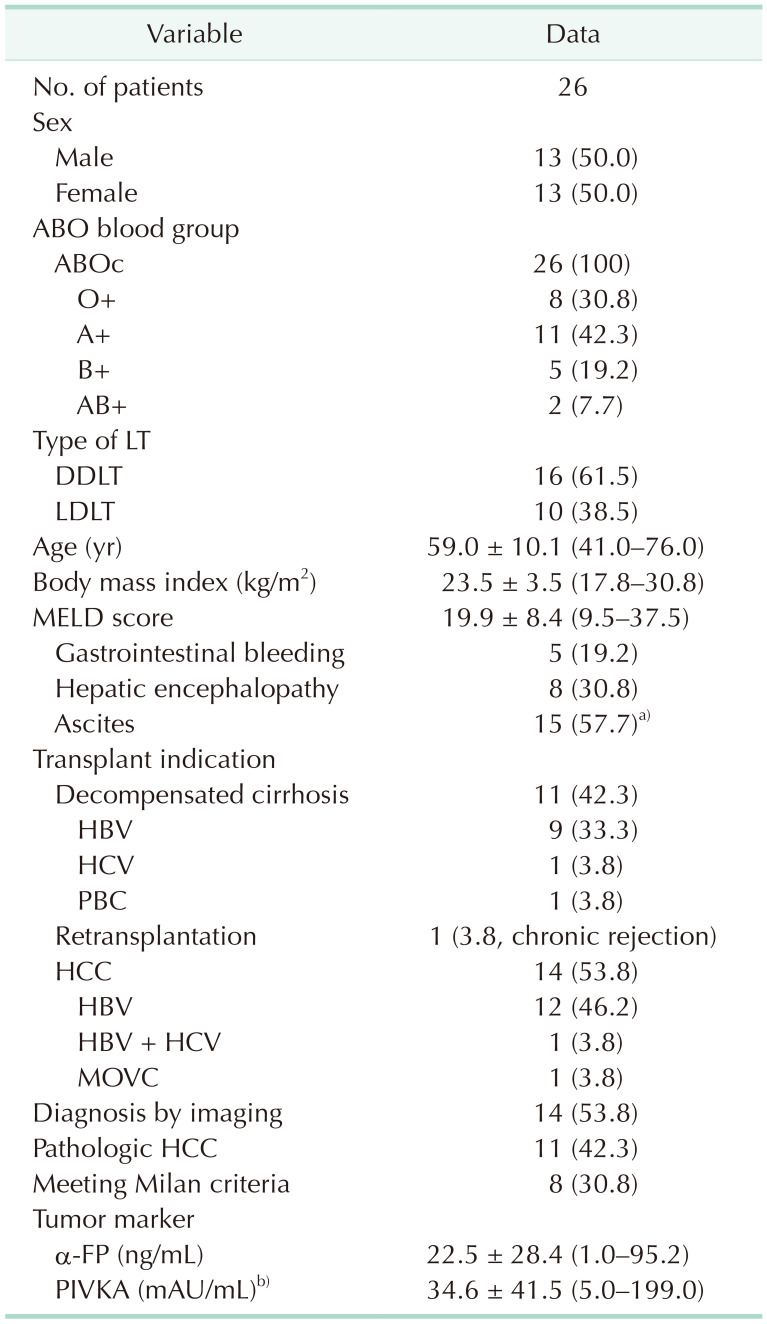

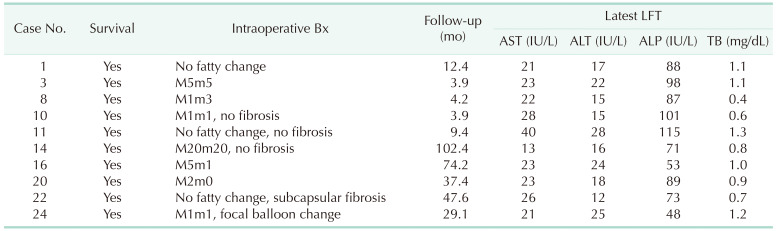

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of recipients

Values are presented as number only, number (%), or mean ± standard deviation (range). LT, liver transplantation; DDLT, deceased donor liver transplantation; LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MOVC, membranous obstruction of the inferior vena cava; PIVKA, prothrombin in vitamin K absence.

a)spontaneous bacterial peritonitis = 3; b)n = 24.

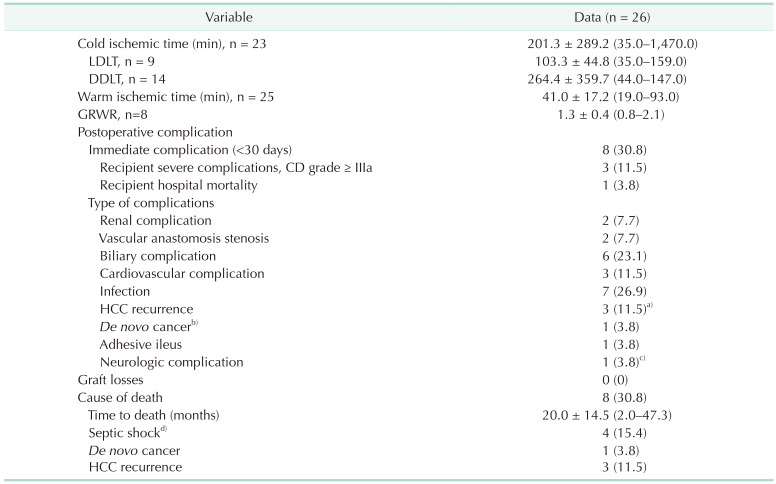

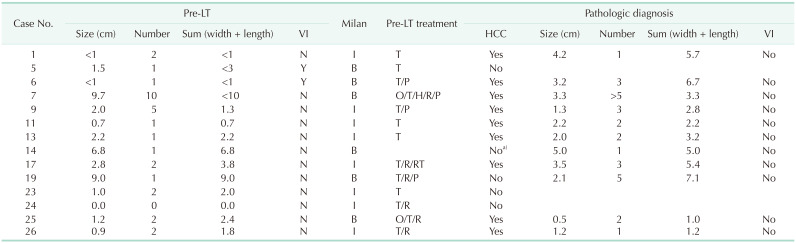

Table 4

Transplantation outcome: operation outcome for recipients

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (range) or number (%).

LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; DDLT, deceased donor liver transplantation; GRWR, graft-to-recipient weight ratio; CD, Clavien-Dindo classification; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

a)Including 1 HCC-cholangiocarcinoma case; b)Klastkin tumor; c)temporal lobe epilepsy. d)Causes of septic shock were duodenal ulcer perforation (n = 1), bile leak accompanying intraabdominal bleeding (n = 1), and pneumonia (n = 2).

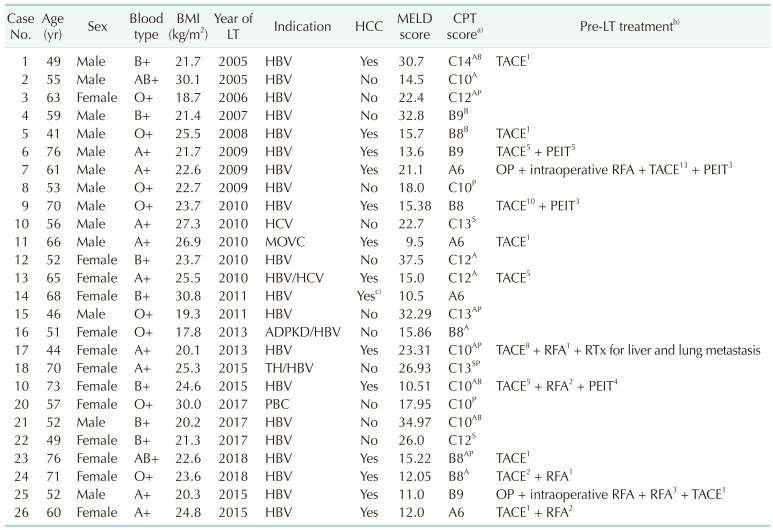

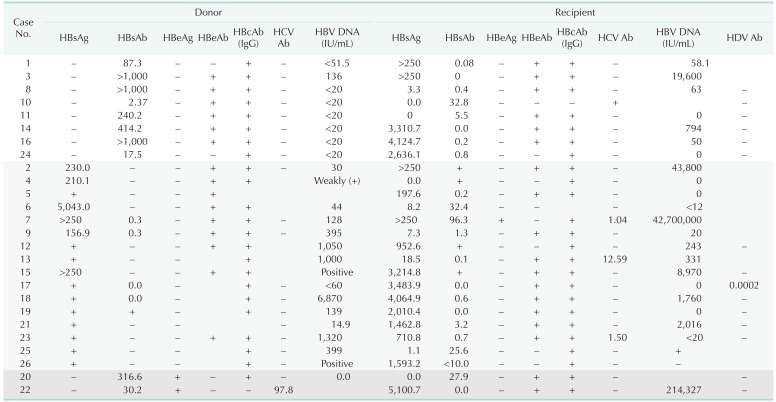

Table 5

Recipient characteristics at the time of LTs (n = 26)

LT, liver transplantation; BMI, body mass index; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; CPT, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; OP, operation; PEIT, percutaneous ethanol injection therapy; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; RTx, radiotherapy; MOVC, membranous obstruction of inferior vena cava; ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; TH, toxic hepatitis; PBC, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

A, ascites; B, gastrointestinal bleeding; P, portosystemic encephalopathy; S, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

a)Symptoms in urgency. b)Superscript numbers mean the numbers of treatment. c)Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

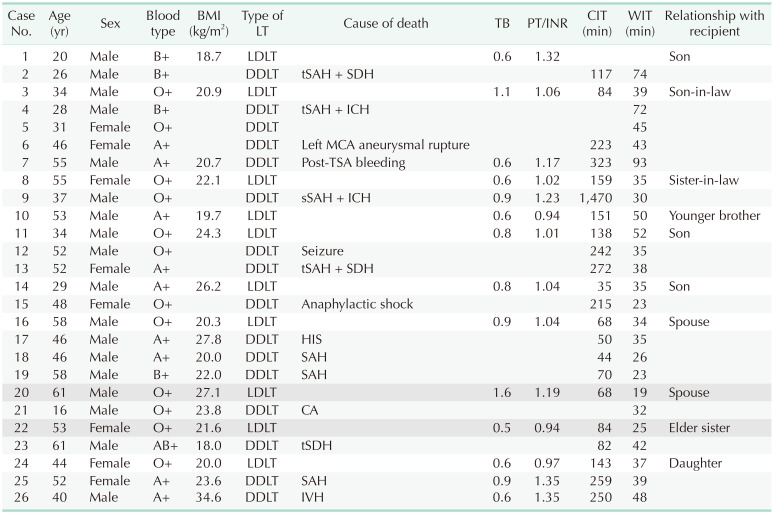

Table 6

Donor characteristics at the time of LT

LT, liver transplantation; BMI, body mass index; TB, total bilirubin; INR, international normalized ratio; CIT, cold ischemic time; WIT, warm ischemic time; LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; DDLT, deceased donor liver transplantation; tSAH, traumatic SAH; SDH, subdural hemorrhage; ICH, intra-cranial hemorrhage; MCA, middle cerebral artery; TSA, transsphenoidal approach; sSAH, spotaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage; HIS, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; CA, cardiac arrest; tSDH, traumatic SDH.

White row, HBcAb (+) HBV DNA (+); light gray row, HBsAg (+); dark gray row, HBsAb (+) HBeAg (+) chronic hepatitis.

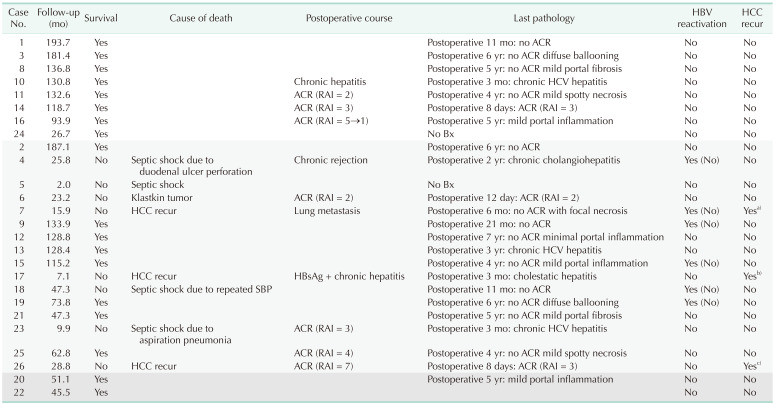

Table 7

Transplantation outcome: detailed outcome of each patient

HBV reactivation was evaluated using 2 criteria. Six reactivation cases were observed when applying the conventional definition (HBsAg positive seroconversion and increase in serum HBV level). In contrast, no reactivation was identified when applying our criteria (notation in parentheses).

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ACR, acute cellular rejection; RAI, rejection activity index; Bx, biopsy.

White row, HBcAb (+) HBV DNA (+); light gray row, HBsAg (+); dark gray row, HBsAb (+) HBeAg (+) chronic hepatitis.

a)Recurred as bone metastasis at 340 days postoperatively. Palliative radiotherapy (RT) was done. b)Recurred in the liver and perihepatic space at 390 days postoperatively. Peritoneal seeding was also accompanied. TACE (transarterial chemoembolization) was done twice. c)Recurred at 249 days postoperatively and metastasis were found at pleura, chest wall, diaphragm, and lung. S7 segmentectomy combined diaphragmatic resection was done for palliation and TACE, chemotherapy, and RT were followed.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download