INTRODUCTION

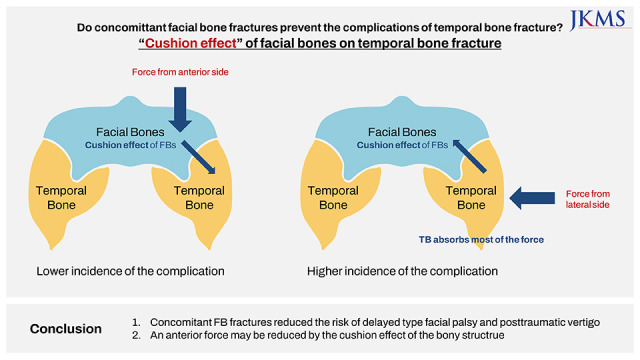

The cranial vault, a bony structure that protects the brain from external force, only provides a barrier to superior and posterior impacts. However, there is an additional barrier against anterior forces: the facial skeleton. Facial bones (FBs) are capable of tolerating the impact of craniofacial injuries, serving as a cushion by absorbing the impact. These fractures act as shock absorbers to dissipate the injury force (the so-called “cushion effect”).

123

Since its introduction by Lee et al. in 1988, there have been several studies on the “cushion effect” of FB fractures.

2 The facial skeleton contains thin and pneumatic cavities and denser bones are located closer to the brain. This structure allows the skeleton to serve as a cushion for absorbing external injury forces.

45 A finite element model simulation showed that fractures in FBs can distribute impact forces and redirect stress to the air-filled sinuses.

6 The cushion effect of FB fractures has been studied in relation to brain injuries, but its association with other types of injuries, such as temporal bone (TB) fracture, is not well established.

TB fracture is frequently seen in head trauma patients, with an incidence of around 30%.

7 Proper management of associated complications, such as hearing loss, facial palsy, and posttraumatic vertigo, is crucial.

8910 In mild cases, a physical examination suffices to detect these complications. However, in severe cases where the patient is unconscious, there may be a delay in identifying and managing the complications, leading to long-term sequelae.

We aimed to find objective indicators to predict complications associated with TB fracture. In this study, we investigated the cushion effect of FB fractures and hypothesize that it may reduce the risk of complications from TB fracture if they occur together. We examined patients with TB fracture and complications such as hearing loss, facial palsy, and posttraumatic vertigo to determine the presence of the cushion effect.

METHODS

Patients

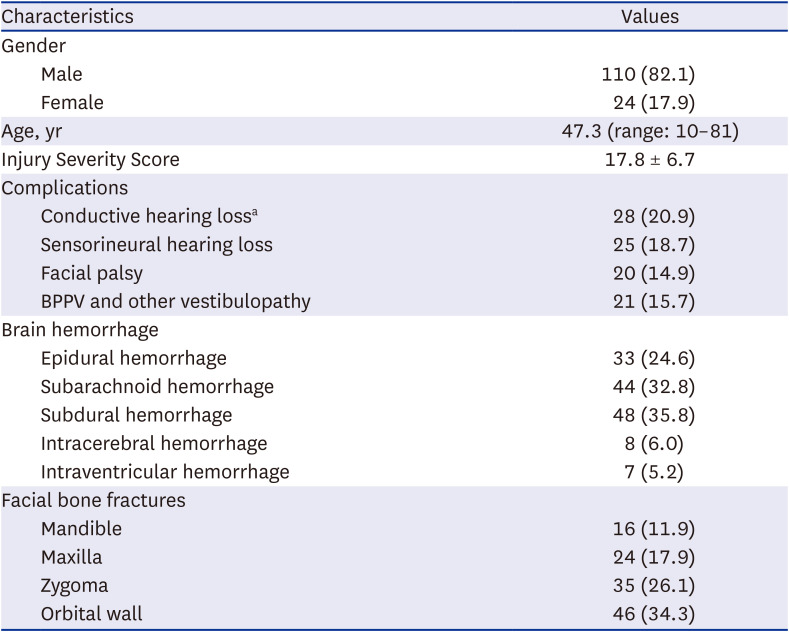

We collected medical records of patients referred to the Department of Otolaryngology from the Trauma Center of Ajou University Hospital between January 2016 and December 2018 for suspected TB fracture. Patients who were transferred to other hospitals within a month and those with confirmed absence of TB fracture after a radiological review were excluded. Age was no criterion. Out of 188 subjects, 54 were excluded. Finally, 134 patients were studied with an average age of 47.3 years (ranging from 10 to 81). We retrospectively reviewed their medical records for demographic information and signs of potential complications related to TB fracture.

Injury severity of trauma

The Injury Severity Score (ISS) was used to assess the severity of trauma.

1112 For the calculation of the score, a body of a person injured is divided into the following six parts: head and neck, face, chest, abdomen or pelvic contents, extremities or pelvic girdle, and other external injuries. Then each part is given a rating based on its severity—no injury (0 point), minor (1), moderate (2), serious (3), severe (4), critical (5), and untreatable (6). The ISS is the sum of the squared numbers of three highest values. For example, if a patient suffered moderate (2) injury on head and neck region, serious (3) on face, severe (4) on abdomen or pelvic contents, and minor (1) external injuries, the ISS of the patient is calculated as 29 (4

2 + 3

2 + 2

2; only three highest regions are calculated). There is one exception in the calculation system; if a score is 6 in any parts, the score is regarded as 75. The ISS ranges from 1 to 75; generally, major trauma is defined as an ISS > 15.

1112

Radiological evaluation

Using temporal bone computed tomography (TBCT), brain CT, and brain magnetic resonance imaging, craniofacial skeleton fractures, facial nerve canal injuries, and brain damage were evaluated by neuroradiologists. FB fractures were classified into maxillary fractures, mandibular fractures, zygomatic fractures, and orbital wall fractures, based on previous studies.

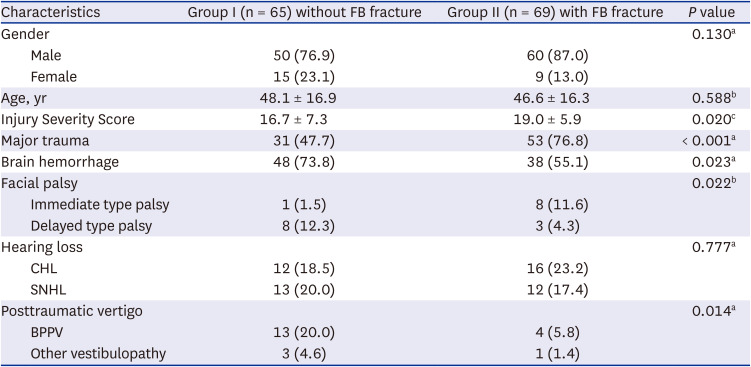

1314 This study did not include nasal bone fractures because they are commonly occurring and can result from even minor impacts. Fractures in orbital part of frontal bone were included as orbital wall fractures. Fractures in the forehead area of the frontal bones were not considered, as that area is considered part of the skull, not the facial skeleton. Patients were divided into two groups according to their concomitant FB fractures: group I (without FB fractures, n = 65) and group II (with FB fracture, n = 69).

Otologic evaluation

If an injured patient exhibited a suspicious TB fracture radiologically, the facial nerve function was evaluated immediately. When the facial movement was asymmetric at the evaluation, we diagnosed it as ‘immediate facial palsy.’ The movement was symmetric initially, but the palsy developed later; it was regarded as ‘delayed facial palsy.’ We used the House-Brackmann grading system as the criteria for facial palsy, where cases with a grade of II or higher were considered to have facial palsy.

1516

The extent of hearing loss was evaluated using pure tone audiometry. The air conduction (AC) and bone conduction (BC) hearing thresholds were documented for each ear. The average pure-tone thresholds at 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz were calculated using a weighted method: [(500 + 1,000 + 1,000 + 2,000 + 2,000 + 4,000)/6]. Hearing loss was diagnosed if the average AC threshold was over 10 dB greater than that of the normal ear. Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) was defined as cases where there was no difference in AC and BC levels or where the difference was less than 10 dB. Conductive hearing loss (CHL) was considered as present when ossicular disruption was clearly identified on TBCT or a difference of ≥ 10 dB between AC and BC that persisted for at least one month after the trauma.

Posttraumatic vertigo was differentiated using the vestibular function test. Maneuvers for diagnosing benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) were performed, including the Dix-Hallpike maneuver and the head-rolling test. Vestibulopathy refers to reduced vestibular function evident on the bithermal caloric test. A canal paresis value > 27% was deemed to indicate pathological value.

Statistical analyses

We used the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test to analyze the categorical data, and the independent t-test to analyze the parametric numerical data. The Mann-Whitney U test was employed to analyze non-parametric numerical data. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify risk factors for complications. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software (ver. 21.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

The present study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ajou University Hospital (approval No. AJIRM-MED-MDB-19-063). Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

DISCUSSION

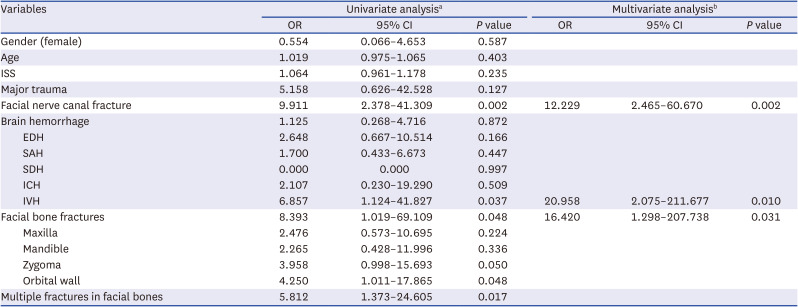

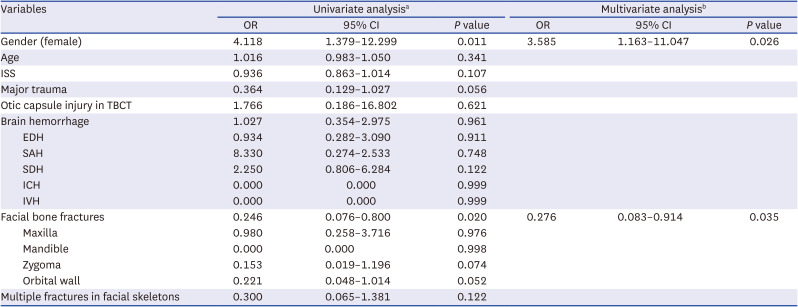

The aim of this study was to explore the idea that FB fracture may have the cushion effect on TB fracture. Our key findings can be summarized as follows: 1) FB fractures were less frequently associated with delayed facial palsy, 2) FB fractures were a risk factor for immediate facial palsy, and 3) FB fractures may lower the risk of posttraumatic vertigo. However, based on these results, it is challenging to conclude that the cushion effect of FB fractures has an impact on the complications of TB fracture. In fact, the second and third findings appear to be contradictory to each other.

The findings indicate that FB fractures were actually a risk factor for immediate facial palsy, rather than providing cushioning. However, during the interpretation of the results, we identified a critical factor that we had previously overlooked—the direction in which the injury force was applied, especially whether the force was applied first to the FB or TB.

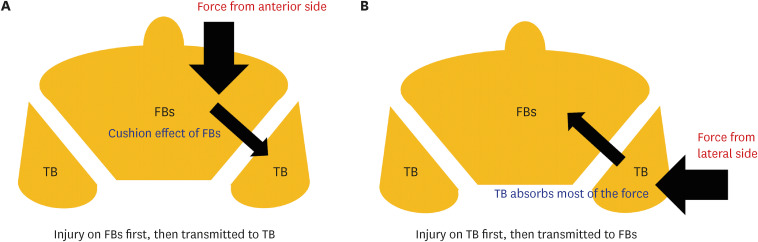

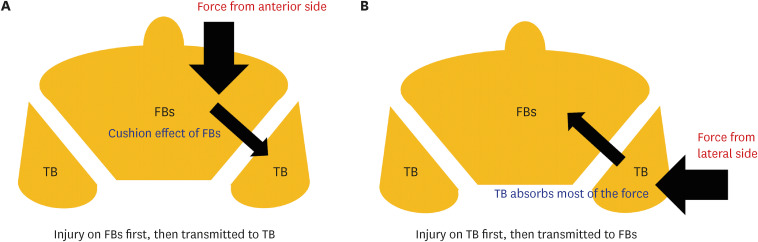

Fig. 1 depicts the possible mechanisms for simultaneously causing FB and TB fractures. If the injury force was initially applied to the FBs and absorbed entirely by them, then a TB fracture might not occur. However, patients who had FB fractures without a TB fracture were not included in this study. On the other hand, if the force was applied to the FB first but not entirely absorbed, a TB fracture may occur (

Fig. 1A), resulting in both FB and TB fractures. In this situation, the occurrence of the complications may be relatively low due to the cushion effect. Then, assuming that the injury caused the TB fracture first (

Fig. 1B), if the force was completely absorbed by TB, FB fractures would not occur. However, the risk of complications would be relatively high. This scenario pertains to patients who have a TB fracture but not FB fractures.

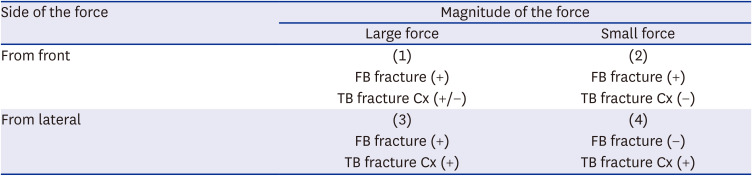

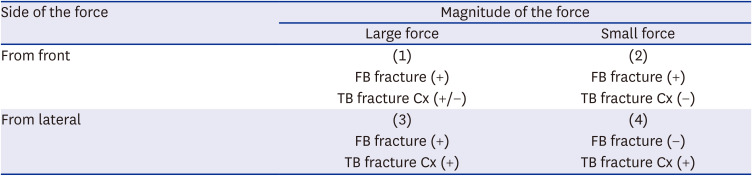

Table 5 provides an overview of the possible scenarios for FB and TB fractures, taking into account the direction and magnitude of the injury force. Scenario (3) is considered to correspond to severe complications, such as immediate facial palsy, and (1) and (2) represent scenarios where the cushion effect of FBs works. Posttraumatic vertigo may be an example of scenario (4).

Fig. 1

Directions of injury force that could be applied to FBs and the TB. (A) An injury may be applied to the FBs first, and then transmitted to the TB. (B) An injury may be applied to the TB first, and then transmitted to the FBs.

FB = facial bone, TB = temporal bone.

Table 5

Magnitude and side of the injury force and the types of fractures

|

Side of the force |

Magnitude of the force |

|

Large force |

Small force |

|

From front |

(1) |

(2) |

|

FB fracture (+) |

FB fracture (+) |

|

TB fracture Cx (+/−) |

TB fracture Cx (−) |

|

From lateral |

(3) |

(4) |

|

FB fracture (+) |

FB fracture (−) |

|

TB fracture Cx (+) |

TB fracture Cx (+) |

This ultimately implies that immediate facial palsy must have resulted from a strong impact force that caused severe trauma, which is consistent with the findings of the multivariate analysis. The risk factors for immediate facial palsy were ‘FB fractures,’ ‘facial nerve canal injury identified on TBCT,’ and ‘IVH.’ Notably, IVH is a marker of severe traumatic injury; thus, these patients would have suffered a significantly greater impact.

17 The forces associated with these injury types would be absorbed by neither the FB nor the TB; therefore, FB and TB fractures would have occurred simultaneously. As a result, the cushion effect may work in some cases, particularly in patients in which the injury occurs from the force applied to the FB. The magnitude and direction of the injury force should be considered together. Although the direction of the force is often unknown in trauma patients, if only it is identified that the force was applied toward TB, FB fractures can be used as a clinical marker. It should be noted that the simultaneous occurrence of TB and FB fractures suggests that a substantial force has been applied, which offsets the protective effect of TB; thus, there is a high possibility of facial nerve injury.

18

Although the magnitude of the injury force would be a major factor in the complications, the multivariate analysis revealed that factors related to the severity, such as ‘ISS’ and ‘major trauma,’ were not associated with any complications. It was thought that this was because the ISS system dealt with all injuries in the whole body. For example, even if the damage to the head and neck region was minor, the score could increase if other regions were severely injured. Meanwhile, there has also been suggested that the ISS system cannot properly reflect the severity.

19 Therefore, although the association was not identified in the multivariate analysis, the magnitude of the injury force should be considered in the management of the complications of TB fracture, along with its direction of the force.

When a TB fracture occurs, the tympanic membrane and mastoid cavities are filled with a bloody discharge; this is called hemotympanum. Similarly, discharge fill of the tympanic cavity is seen in acute otitis media (AOM). In severe cases of AOM, facial palsy and vertigo can occur.

20 For the same reason as cases of AOM, patients with a TB fracture may only experience either delayed facial palsy or posttraumatic vertigo.

Fig. 2A shows an axial image of a patient with fracture and dislocation of the mandible, as well as a TB fracture; blood discharge fills the temporomandibular joint area, but the tympanic cavity remains relatively well-aerated.

Fig. 2B, on the other hand, shows a soft tissue lesion filling mainly the tympanic cavity and external auditory canal; this patient actually experienced posttraumatic vertigo. One more hypothesis we would like to suggest is a decompression effect by the bony fracture. Similar to “compartment syndrome,” when the internal pressure becomes elevated due to the discharge caused by trauma, it could damage the surrounding tissue. If only a TB fracture is present, then the high internal pressure caused by bleeding should be fully covered only by tympanic cavity, similar to that shown in

Fig. 2B. However, when FB fractures occur together with a TB fracture, the pressure may be dispersed, as shown in

Fig. 2A, in which there is no internal pressure, and the risk of facial palsy and posttraumatic vertigo would be low. It might be another hypothesis to explain the results; we acknowledge that the data was insufficient to fully prove the effect. However, this should be taken into consideration for future studies.

Fig. 2

A decompression effect by the bony fracture. (A) The clear left middle ear space is noted. A soft tissue density is mainly shown in the temporomandibular joint area (white arrow). (B) The soft tissue density (white arrow) only fills the middle ear space.

Lt. = left, Rt. = right.

To summarize, the protective “cushion effect” of the FB on a TB fracture may be partially reflected when the injury force is applied mainly to the FB. Especially, in a patient with a TB fracture only (without a FB fracture), it should be recognized that the incidence of delayed facial palsy or posttraumatic vertigo may be higher.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download