1. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018; 39(2):119–177. PMID:

28886621.

2. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE Jr, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR Jr, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 64(24):e139–e228. PMID:

25260718.

3. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 127(4):e362–e425. PMID:

23247304.

4. ONTARGET Investigators. Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358(15):1547–1559. PMID:

18378520.

5. Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, Rouleau JL, Køber L, Maggioni AP, et al. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med. 2003; 349(20):1893–1906. PMID:

14610160.

6. Caldeira D, David C, Sampaio C. Tolerability of angiotensin-receptor blockers in patients with intolerance to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2012; 12(4):263–277. PMID:

22587776.

7. Makani H, Messerli FH, Romero J, Wever-Pinzon O, Korniyenko A, Berrios RS, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized trials of angioedema as an adverse event of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Am J Cardiol. 2012; 110(3):383–391. PMID:

22521308.

8. Kim Y, Ahn Y, Cho MC, Kim CJ, Kim YJ, Jeong MH. Current status of acute myocardial infarction in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2019; 34(1):1–10. PMID:

30612415.

9. Liu J, Masoudi FA, Spertus JA, Wang Q, Murugiah K, Spatz ES, et al. Patterns of use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers among patients with acute myocardial infarction in China from 2001 to 2011: China PEACE-Retrospective AMI Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015; 4(2):e001343. PMID:

25713293.

10. Lee HY, Oh BH. Fimasartan: a new angiotensin receptor blocker. Drugs. 2016; 76(10):1015–1022. PMID:

27272555.

11. Park JB, Sung KC, Kang SM, Cho EJ. Safety and efficacy of fimasartan in patients with arterial hypertension (Safe-KanArb study): an open-label observational study. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2013; 13(1):47–56. PMID:

23344912.

12. Quan H, Oh GC, Seok SH, Lee HY. Fimasartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, ameliorates an in vivo zebrafish model of heart failure. Korean J Intern Med. 2020; 35(6):1400–1410. PMID:

32164398.

13. Sim DS, Jeong MH, Song HC, Kim J, Chong A, Bom HS, et al. Cardioprotective effect of fimasartan, a new angiotensin receptor blocker, in a porcine model of acute myocardial infarction. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30(1):34–43. PMID:

25552881.

14. Lee J, Lee JS, Park SH, Shin SA, Kim K. Cohort profile: The National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC), South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46(2):e15. PMID:

26822938.

15. Shin DW, Cho B, Guallar E. Korean national health insurance database. JAMA Intern Med. 2016; 176(1):138.

16. Lee SR, Lee HJ, Choi EK, Han KD, Jung JH, Cha MJ, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and liver disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 73(25):3295–3308. PMID:

31248551.

17. Chun CB, Kim SY, Lee JY, Lee SY. Republic of Korea: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2009; 11(7):1–184.

18. Kimm H, Yun JE, Lee SH, Jang Y, Jee SH. Validity of the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in korean national medical health insurance claims data: the Korean Heart Study (1). Korean Circ J. 2012; 42(1):10–15. PMID:

22363378.

19. Brown NJ, Vaughan DE. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Circulation. 1998; 97(14):1411–1420. PMID:

9577953.

20. Lim S, Choo EH, Choi IJ, Ihm SH, Kim HY, Ahn Y, et al. Angiotensin receptor blockers as an alternative to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34(45):e289. PMID:

31760711.

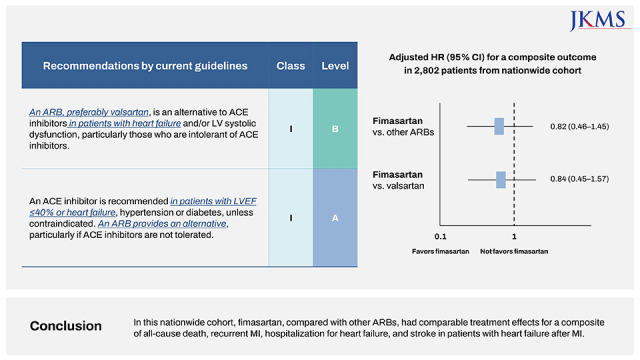

21. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Colvin MM, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017; 136(6):e137–e161. PMID:

28455343.

22. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021; 42(36):3599–3726. PMID:

34447992.

23. Jeong HC, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, Chae SC, Hur SH, Hong TJ, et al. Comparative assessment of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction: surmountable vs. insurmountable antagonist. Int J Cardiol. 2014; 170(3):291–297. PMID:

24239100.

24. Burnier M. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers. Circulation. 2001; 103(6):904–912. PMID:

11171802.

25. Abraham HM, White CM, White WB. The comparative efficacy and safety of the angiotensin receptor blockers in the management of hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases. Drug Saf. 2015; 38(1):33–54. PMID:

25416320.

26. Kjeldsen SE, Stålhammar J, Hasvold P, Bodegard J, Olsson U, Russell D. Effects of losartan vs candesartan in reducing cardiovascular events in the primary treatment of hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2010; 24(4):263–273. PMID:

19890371.

27. Oparil S, Williams D, Chrysant SG, Marbury TC, Neutel J. Comparative efficacy of olmesartan, losartan, valsartan, and irbesartan in the control of essential hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2001; 3(5):283–291. PMID:

11588406.

28. Paik SH, Chi YH, Lee JH, Han HS, Lee KT. Pharmacological profiles of a highly potent and long-acting angiotensin II receptor antagonist, fimasartan, in rats and dogs after oral administration. Biol Pharm Bull. 2017; 40(7):992–1001. PMID:

28674263.

29. Lee SE, Kim YJ, Lee HY, Yang HM, Park CG, Kim JJ, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of fimasartan, a new angiotensin receptor blocker, compared with losartan (50/100 mg): a 12-week, phase III, multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, dose escalation clinical trial with an optional 12-week extension phase in adult Korean patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension. Clin Ther. 2012; 34(3):552–568. 568.e1–559. PMID:

22381711.

30. Lee H, Kim KS, Chae SC, Jeong MH, Kim DS, Oh BH. Ambulatory blood pressure response to once-daily fimasartan: an 8-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active-comparator, parallel-group study in Korean patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension. Clin Ther. 2013; 35(9):1337–1349. PMID:

23932463.

31. Chung WB, Ihm SH, Jang SW, Her SH, Park CS, Lee JM, et al. Effect of fimasartan versus valsartan and olmesartan on office and ambulatory blood pressure in Korean patients with mild-to-moderate essential hypertension: a randomized, double-blind, active control, three-parallel group, forced titration, multicenter, phase IV study (Fimasartan Achieving Systolic Blood Pressure Target (FAST) study). Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020; 14:347–360.

32. Han J, Park SJ, Thu VT, Lee SR, Long T, Kim HK, et al. Effects of the novel angiotensin II receptor type I antagonist, fimasartan on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 168(3):2851–2859. PMID:

23642815.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download