Abstract

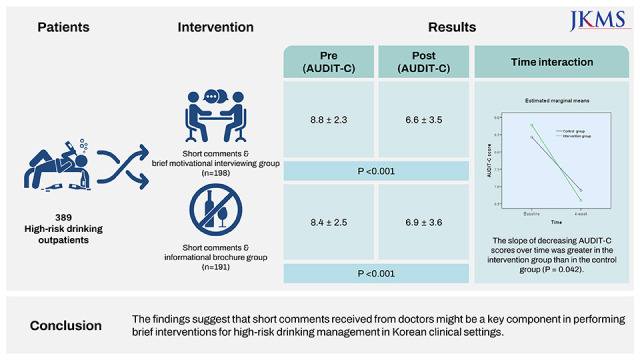

A motivational interviewing (MI)-based brief intervention was performed with high-risk drinking outpatients screened at internal medicine settings in Korea after the doctor advised them to reduce alcohol consumption. Participants were assigned to a MI group or a control group where they received a brochure with information on the harm of high-risk drinking and tips on managing drinking habits. Four-week follow-up results showed that Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Concise (AUDIT-C) scores decreased in the MI group and the control group compared to baseline scores. The difference between groups was not significant; however, group by time interaction was significant between the two groups: the slope of decreasing AUDIT-C scores over time was greater in the intervention group than in the control group (P = 0.042). The findings suggest that short comments received from doctors might be a key component in performing brief interventions for high-risk drinking management in Korean clinical settings.

Graphical Abstract

High-risk drinking increases the risk of physical diseases, such as cirrhosis, liver cancer, and cardiovascular disease, as well as mental disorders, such as depression and alcohol use disorders.1234 While the overall rates of alcohol use in Korea are around the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development average, the rate of heavy episodic drinking or binge drinking is high.56 Further, the average number of liqueur drinks consumed in one sitting has almost tripled from 2.2 cups in 2013 to 6.0 cups in 2016.7 This high-risk drinking rate results in a high mortality rate due to alcohol-related diseases. According to statistics, the mortality rate caused by alcohol-related diseases almost doubled from 5.6% in 1998 to 9.4% in 2017. Alcohol-related liver diseases account for the highest proportion of alcohol-related deaths, representing 77.2% of all alcohol-related deaths in Korea.8 Despite the seriousness of alcohol problems, therapeutic interventions have not been properly provided in Korea.9

Considering the high prevalence of high-risk drinking and negative attitudes toward seeking mental health services, early intervention for alcohol problems in primary care settings or non-psychiatric internal medicine settings is important. According to recent studies, 20–30% of patients in non-psychiatric outpatient clinics were found to be in the high-risk drinking group. However, it has been reported that there is no proper treatment or referral to specialized treatment for their drinking problems, and only basic advice is provided (e.g., you need to stop drinking) with the treatment for the physical disease the patient is seeking help for.101112 Brief interventions have been developed for primary care settings that have demonstrated effectiveness,13 and these programs are reflected in the clinical practice guidelines in Europe, Australia, the United States, and Korea. However, this has not yet been properly implemented in Korea,14 and dissemination strategies that fit reality are needed.15

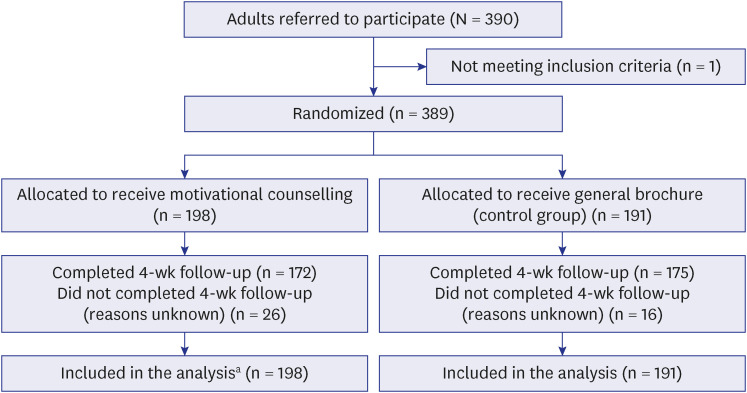

This study investigated whether there would be a difference in high-risk drinking behavior after participation in motivational interviewing (MI)-based brief counseling compared to standard service under the same physician’s recommendation in internal medicine settings. This was a double-blind, parallel-group randomized controlled trial (RCT) with a 1:1 allocation ratio (Fig. 1). The participants were outpatients aged 19–65 years screened as high-risk drinkers via routine opportunistic screening by doctors from two internal medicine settings in South Korea. On the day of visiting the outpatient clinic, participants with an Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Korean version (AUDIT-K)1617 total score of ten (for men) or six (for women) or higher4 were referred to an intervention team. Patients of Korean nationality consented to participate in the study. Patients requiring outpatient visits at least once a week, psychiatric patients, or patients with suspected cognitive impairment were excluded. Sample size was calculated according to Jo et al.18 A total of 366 participants were required to detect a 0.99 difference in AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions scores with a 5% significance level, 80% power, and 10% attrition. Therefore, 183 participants per group were required.

The participants were randomly allocated to receive either MI or a brochure. The sequence of allocation was generated by the first author using Excel 2013 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), and the sequence was in blocks of four stratified by site. The allocation concealment was maintained using opaque and sealed envelopes, and administrative personnel unrelated to the conducting of the study kept the envelopes. The participants and researchers assessing the outcomes were blinded to the allocation.

The MI brief intervention was structured as a single session lasting approximately 15 minutes. On the day that an internal medicine outpatient was detected as a high-risk drinker in an opportunistic screening through the AUDIT-K, a trained psychologist provided the MI-based brief intervention and encouraged the patient by phone calls a week later. The brief intervention comprised feedback on the results of the screening test, information on the harm of drinking, the benefit of reducing drinking, motivational enhancement, and the development of a personal plan to reduce consumption. The control group received an A4-size double-sided brochure with information on the harm of high-risk drinking and tips on managing drinking habits. The physician briefly explained the screening results and encouraged patients to see a counselor outside of the office. The double-blind procedure was maintained by physicians giving participants no information about the type of intervention and preventing physicians and outcome evaluators from knowing the group to which the participants belonged.

The AUDIT-Concise (AUDIT-C),19 which consists of three questions from the 10-item AUDIT, was used to measure severity of problematic alcohol use via a 1:1 phone interview four weeks after the brief intervention. Telephone interviews were conducted by a researcher who was blinded to the purpose of this study. Total AUDIT-C scores can range from 0 to 12. A general linear model was used with the AUDIT-C total score as the dependent variable and group as a factor variable, controlling for the baseline AUDIT-C score. The missing value of the outcome variable was imputed using the last observation carried forward method. All analyses were based on an intention-to-treat dataset. All analyses used two-sided tests and a significance level of P < 0.05. SPSS Statistics 24 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

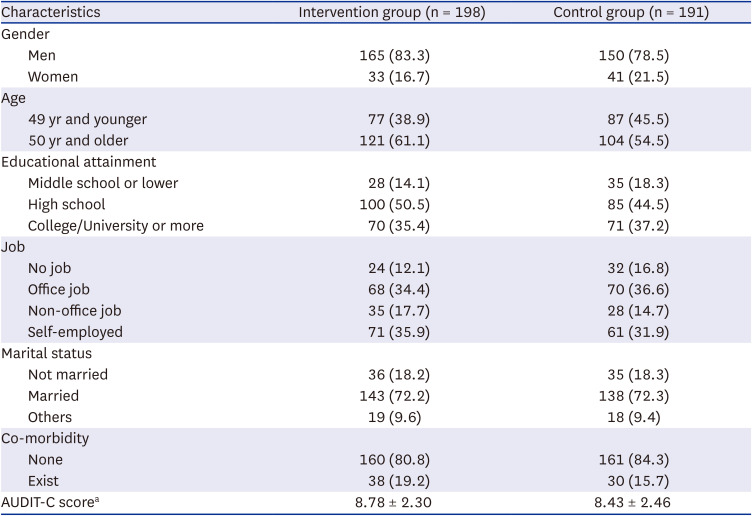

A total of 389 participants were randomized between June 2020 and February 2021. One participant was excluded from the randomization because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Follow-up assessment was completed for 172 (86.9%) participants in the intervention group and 175 (91.6%) participants in the control group (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants.

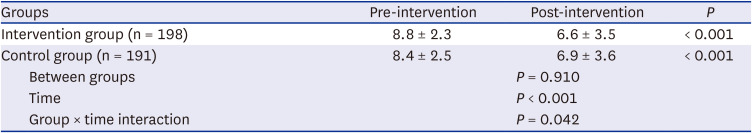

Table 2 shows the changes in AUDIT-C scores. At baseline, the mean scores and standard deviations for the AUDIT-C were 8.8 ± 2.3 and 8.4 ± 2.5 for the intervention and control groups, respectively. It was observed that the AUDIT-C score was significantly lower at the four-week follow-up compared to the baseline score in both groups (P < 0.001): the AUDIT-C score was 6.6 ± 3.5 in the intervention group and 6.9 ± 3.6 in the control group four weeks later. Different patterns of decline in AUDIT-C scores were found between the two groups over time (group-by-time interaction): the slope of decreasing AUDIT-C scores over time was greater in the intervention group than in the control group (P = 0.042).

In this randomized controlled study, both the intervention and control groups showed a statistically significant decrease in AUDIT-C scores from the time of assessment to four weeks after the intervention. It was also confirmed that the decrease in AUDIT-C scores was greater in the intervention group compared to the control group. These results indicate that alcohol consumption can be reduced through simple interventions for outpatients in internal medicine clinics who need to stop drinking or reduce their use of alcohol.

In this study, considering the reality of internal medicine clinics at a university hospital in Korea, where many patients have to be treated in a limited amount of time, the doctor briefly explained only the screening test results, and a psychologist performed a brief intervention. Evidence already exists that brief interventions are sufficiently effective when provided by a nurse or counselor.20 Therefore, considering the medical field situation in Korea, a brief intervention provided by a trained counselor or providing a brochure after a doctor advises the patient to stop drinking or reduce alcohol intake can be a strategy to increase the applicability of the brief intervention program.

In other studies, psychologists or nurses often provide brief interventions lasting 20 to 30 minutes, which is considered an extended brief intervention and may be more effective than advice giving or brief conversations about reducing alcohol intake with a doctor.2021 Therefore, the MI intervention in this study, which was conducted by a psychologist for about 15 minutes, was moderately intense and was more than advice-giving or conversation as an intervention but less than what would be considered an extended brief intervention.

In this study, a statistically significant decrease in AUDIT-C scores was observed in the control group as well. For the control group, the psychologist provided a brochure after the doctor provided a brief explanation of the screening test results. Generally, it is beyond the usual care for a doctor to explain alcohol screening results. In addition, according to previous studies, feedback and advice on test results within five minutes provided by doctors can be viewed as a short version of a brief intervention, and it has been reported that this is also effective in reducing problematic drinking.1522 Therefore, it is inferred that the control group received a short version of a brief intervention in this study, which also had an effect on drinking behavior.

This study showed the results of a short-term follow-up assessment four weeks after the intervention. Because the slope of decrease in the AUDIT-C scores was greater in the intervention group than in the control group, follow-up for a longer period of time is recommended to confirm the effectiveness of the MI-based brief intervention. Nevertheless, the doctor’s advice to reduce alcohol consumption might be an important component in decreasing alcohol intake at least by the end of four weeks.

This RCT was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Uijeongbu St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea (approval No. UC19QNDI0078). Informed consent was obtained from all participants when they were enrolled. This RCT was registered at the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS, http://cris.nih.go.kr), number KCT0004748.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Dong Joon Kim and Dr. Ki-Tae Suk, Hallym University College of Medicine and Dr. Chang wook Kim and Dr. Hee-yeon Kim, Uijongbu St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, for adoption of the screening and brief intervention to their clinical settings for this study. The authors also thank psychologists for their performance of brief motivational interviews for or providing alcohol use-related brochures to outpatients.

Notes

Funding: This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Mental Health R&D Project funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HL19C0024) and by the Research Program funded by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (fund code 2021-11-023). The Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea, and the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

1. Rehm J, Baliunas D, Borges GL, Graham K, Irving H, Kehoe T, et al. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2010; 105(5):817–843. PMID: 20331573.

2. Gao C, Ogeil R, Lloyd B. Alcohol’s burden of disease in Australia. Updated 2014. Accessed August 16, 2022.

https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/Alcohols-burden-of-disease-in-Australia.pdf

.

3. Jang WY, Chung WJ, Jang BK, Hwang JS, Lee HJ, Hwang MJ, et al. Changes in characteristics of patients with liver cirrhosis visiting a tertiary hospital over 15 years: a retrospective multi-center study in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(29):e233. PMID: 32715667.

4. Park SC, Lee SK, Oh HS, Jun TY, Lee MS, Kim JM, et al. Hazardous drinking-related characteristics of depressive disorders in Korea: the CRESCEND study. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30(1):74–81. PMID: 25552886.

5. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health at a glance 2019 - OECD indicators. Updated 2019. Accessed August 16, 2022.

https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Health-at-a-Glance-2019-Chartset.pdf

.

6. World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Updated 2018. Accessed August 16, 2022.

http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/

.

7. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (KR). A 2016 survey on alcohol consumption and drinking behavior. Updated 2016. Accessed August 16, 2022.

http://www.mfds.go.kr/index.do?mid=675&pageNo=3&seq=33152&cmd=v

.

8. Statistics Korea. Causes of death statistics in 2017. Updated 2018. Accessed August 16, 2022.

http://kostat.go.kr/assist/synap/preview/skin/miri.html?fn=8ddd718430667730202529&rs=/assist/synap/preview

.

9. National Center for Mental Health (KR). National mental health statistics 2020. Updated 2021. Accessed May 16, 2023.

https://www.ncmh.go.kr:2453/viewer/skin/doc.html?fn=20211111165418134393_1.pdf&rs=/viewer/result/202305/

.

10. Korean Association for the Study of the Liver. White Paper on Liver Diseases in Korea. Seoul, Korea: Korean Association for the Study of the Liver;2013.

11. Jarque-López A, González-Reimers E, Rodríguez-Moreno F, Santolaria-Fernández F, López-Lirola A, Ros-Vilamajo R, et al. Prevalence and mortality of heavy drinkers in a general medical hospital unit. Alcohol Alcohol. 2001; 36(4):335–338. PMID: 11468135.

12. Rosón B, Corbella X, Perney P, Santos A, Stauber R, Lember M, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and risk factors for non-recording of alcohol use in hospitals across Europe: the ALCHIMIE study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016; 51(4):457–464. PMID: 26818195.

13. World Health Organization. Brief Intervention for Hazardous and Harmful Drinking: A Manual for Use in Primary Care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2001.

14. Kim JW, Lee BC, Kang TC, Choi IG. The current situation of treatment systems for alcoholism in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2013; 28(2):181–189. PMID: 23400047.

15. World Health Organization. WHO Alcohol Brief Intervention Training Manual for Primary Care. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe;2017.

16. Joe KH, Chai SH, Park A, Lee HK, Shin IH, Min SH. Optimum cut-off score for screening of hazardous drinking using the Korean version of Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT-K). J Korean Acad Addict Psychiatry. 2009; 13(1):34–40.

17. Jung JG, Kim JS, Kim GJ, Oh MK, Kim SS. Brief insight-enhancement intervention among patients with alcohol dependence. J Korean Med Sci. 2011; 26(1):11–16. PMID: 21218023.

18. Jo SJ, Lee HK, Kang K, Joe KH, Lee SB. Efficacy of a web-based screening and brief intervention to prevent problematic alcohol use in Korea: results of a randomized controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019; 43(10):2196–2202. PMID: 31386203.

19. Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007; 31(7):1208–1217. PMID: 17451397.

20. Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Muirhead C, Campbell F, Pienaar ED, Bertholet N, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; 2(2):CD004148. PMID: 29476653.

21. Gentilello LM, Ebel BE, Wickizer TM, Salkever DS, Rivara FP. Alcohol interventions for trauma patients treated in emergency departments and hospitals: a cost benefit analysis. Ann Surg. 2005; 241(4):541–550. PMID: 15798453.

22. Beyer FR, Campbell F, Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Saunders JB, Pienaar ED, et al. The Cochrane 2018 review on brief interventions in primary care for hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption: a distillation for clinicians and policy makers. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019; 54(4):417–427. PMID: 31062859.

Fig. 1

Study participant flow and follow-up rates.

AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Concise.

aIntention-to-treat analysis adopted. Primary outcome measure was AUDIT-C score. The score range for the AUDIT-C is 0 to 12.

Table 1

Baseline demographic and drinking characteristics

Table 2

Outcome data: change in Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Concise scorea

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download