This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background

We analyzed whether a maternity waiting home (MWH) for pregnant women in an obstetrically underserved area of Gangwon-do in Korea, which has been in operation since August 2018, has improved the accessibility of a maternity hospital and pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

We compared and analyzed the accessibility of maternity hospitals for 170 pregnant women who applied for the MWH from August 2018 to May 2022. Among the 170 participants, 64 were MWH users and 106 non-users. The effect on pregnancy outcomes between MWH users and non-users was analyzed in the 160 people who achieved a pregnancy outcome.

Results

Although the average distance and travel time from the pregnant women’s residence in the obstetrically underserved area to a maternity hospital were 56.4 ± 1.6 km and 63.4 ± 1.4 minutes, respectively, the average distance between the MWH and the MWH users’ maternity hospital was 2.7 ± 0.2 km, and the travel time was 10.7 ± 0.6 minutes. The distance was 55.6 km closer on average and the travel time 54.1 minutes shorter. MWH users gave birth at a significantly later gestation age (38.9 ± 0.2 vs. 38.3 ± 0.15 weeks, P = 0.024) and to infants with heavier birth weights (3,300 ± 60 vs. 3,100 ± 50 gm, P = 0.024) compared with non-users. The rate of Cesarean section was significantly higher in the MWH users (47.5% vs. 44.6%, P = 0.047). The MWH users tended to be associated with a lower rate of neonatal intensive care unit admission (5.1% vs. 11.0%, P = 0.204), lower birth weight (< 2.5 kg) (1.7% vs. 8.0%, P = 0.155), and lower fetal death rate in the uterus (0% vs. 1.0%, P = 1.0) compared with non-users, but the differences were not significant.

Conclusion

The MWH helped pregnant women in obstetrically underserved areas by improving accessibility to a maternity hospital and lengthening gestation. As a result, neonatal birth weight was heavier for MWH users than non-users. MWHs in Korea can provide an alternative way to improve accessibility to maternity healthcare for pregnant women in obstetrically underserved areas, where it is difficult to establish maternity hospitals, and thereby will improve their pregnancy outcomes.

Keywords: Maternity Waiting Home, Maternal Health, Neonatal Health, Obstetrically Underserved Area

INTRODUCTION

The total fertility rate in Korea in 1983 was 2.06, which is considered low. Korea entered the lowest-low fertility era in 2002, when the total fertility rate was 1.178. The total fertility rate in 2021 was 0.81, which is the lowest in the history of the Republic of Korea. The decreased number of births affects society overall, particularly the conventional maternity healthcare system. The number of maternity hospitals was 1,371 in 2003 but decreased by 62.2% to 518 in 2020.

1 The decrease in the number of maternity hospitals has negatively affected maternal and neonatal health.

The maternal mortality ratio in 2011 was 17.2, which was 2.1 times higher than the average value (8.2) of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries and 4.2 times higher than that (4.1) of Japan.

2 In particular, the closure of maternity hospitals occurred in succession in rural areas where there is an absolute lack of fertile women and newborns. As a result, maternal and neonatal health in rural areas worsened. In 2019, the national maternal mortality ratio was 9.9, whereas the maternal mortality ratio of Gangwon-do, a typical rural province, was 24.2.

3 According to a 2018 study, the miscarriage rate in obstetrically underserved areas was 4.6%, which was higher than that (3.56%) in a maternity medical service area.

4 The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended continuous treatment during pregnancy and childbirth to reduce the maternal mortality ratio and rate of immediate visits to a maternity hospital during an emergency, emphasizing the importance of accessibility to maternity medical services.

5

To improve accessibility to maternity medical services in obstetrically underserved areas, the Ministry of Health and Welfare has been operating the Obstetrical Underserved Area Supporting Project since 2011, which helped 31 rural local governments open maternity hospitals by 2021. Despite these efforts, 63 of 250 local governments in the country still have no maternity hospitals.

1 This indicates that opening maternity hospitals in obstetrically underserved areas to improve accessibility to maternity medical services is limited for various reasons, including a lack of medical staff, indifference of the local government and rapid closure of maternity hospital in rural areas.

An alternative to improve the accessibility of maternity medical service to pregnant women in obstetrically underserved areas is needed where it is difficult to open maternity hospitals in a short time.

The WHO presented four strategies to improve the medical accessibility of maternity facilities to pregnant women to reduce maternal death.

6 The first is to dispatch a medical service team to patients in need of medical services. The second is to operate an emergency transport team to transport patients quickly. The third strategy is to establish maternity hospitals in obstetrically underserved areas. The last strategy is to build maternity waiting homes (MWHs) for pregnant women near a maternity hospital.

In countries or regions where it is difficult for pregnant women to access maternity hospitals due to socioeconomic, cultural, or geographic barriers, MWHs have opened near maternity hospitals, since 1960, to help improve maternal and neonatal healthcare.

7 MWHs are operated differently depending on the country and region. According to the WHO, MWHs are defined as residential facilities used to prepare for obstetrical emergencies. They are located near maternity hospitals and are a place where pregnant women living far from a maternity hospital can stay. These facilities allow pregnant women to stay from the final weeks of their pregnancy to childbirth and are managed in association with birthing attendants or birth healthcare workers.

8 These MWHs have not only been introduced in low-income countries but also in the US and Europe, which lacked maternity hospitals in the early 20th century.

6

Despite the advanced healthcare system of National Health Insurance service in Korea, the issue of obstetrically underserved areas caused by a low birth rate threatens maternal and neonatal health. Local governments have developed various policies to address this issue. Gangwon-do and Kangwon National University Hospitals have been operating an MWH for pregnant women who live in obstetrically underserved areas since 2018 for the first time in Korea.

The purpose of this study was to analyze the current status of MWH use based on the experience of 4 years of operation and to determine whether an MWH is a good alternative to address the issue of obstetrically underserved areas.

METHODS

This retrospective study analyzed 170 pregnant women living in obstetrically underserved areas who applied to the MWH operated by Kangwon National University Hospital from August 8, 2018 to May 31, 2022. Among the 170 participants, 64 were MWH users and 106 non-users. The women’s general characteristics at that time, reason for application, and pregnancy information were verified on their MWH application forms. Pregnancy outcome information was acquired for 59 MWH users and 101 non-users. Their pregnancy outcomes were obtained from maternity hospitals. The average distance and travel time from the pregnant woman’s residences to the maternity hospital were calculated using the NAVER Map Service. The advantages and disadvantages of the MWH were identified in a discharge survey. Factors such as the rates of Cesarean section, low birth weight, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, and fetal death in utero were compared as pregnancy outcomes. Preterm birth was defined as birth at less than 37 weeks of gestation, and low birth weight was defined as less than 2.5 kg.

Establishment of the MWH at Kangwon National University Hospital

Since 2018, Kangwon National University Hospital has been operating an MWH for pregnant women residing in Hongcheon, Cheolwon, Hwacheon, Yanggu, and Inje, which are obstetrically underserved areas in Gangwon-do. MWHs aim to increase accessibility to maternity hospitals for pregnant women living in obstetrically underserved areas and to improve maternal and neonatal healthcare. Korea had no prior experience with operating an MWH. Thus, after the preliminary survey on necessities, intent to participate, residence period, and room size conducted in 103 pregnant women living in five areas, an MWH was designed for operation.

Based on the results of the preliminary survey, the apartment managed by the Korean Land and Housing Corp. was rented to operate the MWH in Chuncheon of Gangwon-do, a city located with the maternity hospital used pregnant women in five areas. The MWH operated by Kangwon National University Hospital is 84.89 m2 in size and allows a family to stay to prevent infection. The MWH provides a clean, crime-free environment and laundry services but does not offer any meals, to prevent food poisoning. Rice and water to cook for a meal were offered once upon entrance to the facility.

After the MWH participants filled out the application form and submitted it to the MWH management team, a selection committee chose pregnant women to stay in the MWH. The committee assesses the applicants based on age, gestational age, distance to hospital, travel time, admission number before application, and the number of risk factors for high-risk pregnancy including preterm labor, short cervix and hypertensive pregnancy. The residence period in the MWH was 24 days, from 3 weeks before delivery to 3 days after delivery. After childbirth, each woman participated in a survey of satisfaction before leaving the MWH.

Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics were compared using the t-test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Continuous and categorical variables are described as means ± standard deviation and percentages, respectively. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics statement

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kangwon National University Hospital (approval No. KNUH 2021-07-001-001). Informed consent was waived by the committee because this was a retrospective chart review study.

RESULTS

General characteristics

The average age of the 170 participants was 33.4 ± 0.4 years. The MWH users were significantly older than non-users (34.5 ± 0.6 vs. 32.7 ± 0.5 years,

P = 0.021). The average distance between the participants’ residences to the maternity hospital was 56.4 ± 1.6 km, and the average travel time was 63.4 ± 1.4 minutes. Although the travel distance was longer for MWH users than non-users, no significant difference was detected. Approximately 22.4% of the participants had a history of admission to a maternity hospital before their application. All participants applied to the MWH due to the long distance that they had to travel to a maternity hospital. Most participants did not have guardians for a long time (62.9%) and were high-risk pregnant women (56.5%) (

Table 1).

Table 1

General characteristics of MWH users and non-users at the time of application

|

Characteristics |

MWH users (n = 64) |

MWH non-users (n = 106) |

Total (N = 170) |

P value (users vs. non-users) |

|

Age, yr |

34.5 ± 0.6 |

32.7 ± 0.5 |

33.4 ± 0.4 |

0.021 |

|

Gestational age at application |

28.1 ± 0.8 |

27.9 ± 0.5 |

27.9 ± 0.5 |

0.826 |

|

Distance to maternity hospital at application, km |

58.3 ± 2.6 |

55.2 ± 2.0 |

56.4 ± 1.6 |

0.335 |

|

Travel time to maternity hospital at application, min |

64.8 ± 2.4 |

62.5 ± 1.8 |

63.4 ± 1.4 |

0.439 |

|

Nulliparity |

38 (59.4) |

64 (60.4) |

102 (60.0) |

0.897 |

|

Admission rate before application |

16 (25.0) |

22 (20.8) |

38 (22.4) |

0.520 |

|

Reasons for applying (multiple choice) |

|

|

|

|

|

Long distance to the maternity hospital |

64 (100) |

106 (100) |

170 (100) |

- |

|

No guardian for long time |

36 (56.3) |

71 (67.0) |

107 (62.9) |

0.160 |

|

Frequent visits to the hospital |

6 (9.4) |

6 (5.7) |

12 (7.1) |

0.371 |

|

Diagnosis of a high-risk pregnancy |

40 (62.5) |

56 (52.8) |

96 (56.5) |

0.218 |

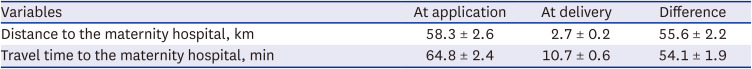

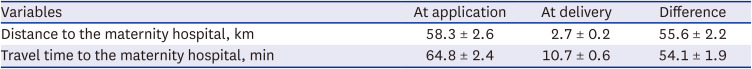

The average residence period of the MWH users was 18.5 ± 8.9 days. The average distance between the MWH and MWH users’ maternity hospital was 2.7 ± 0.2 km, and the average travel time was 10.7 ± 0.6 minutes. As a result, the distance was 55.6 km closer on average and the travel time 54.1 minutes shorter (

Table 2).

Table 2

Distance and travel time to the maternity hospital for maternity waiting home users

|

Variables |

At application |

At delivery |

Difference |

|

Distance to the maternity hospital, km |

58.3 ± 2.6 |

2.7 ± 0.2 |

55.6 ± 2.2 |

|

Travel time to the maternity hospital, min |

64.8 ± 2.4 |

10.7 ± 0.6 |

54.1 ± 1.9 |

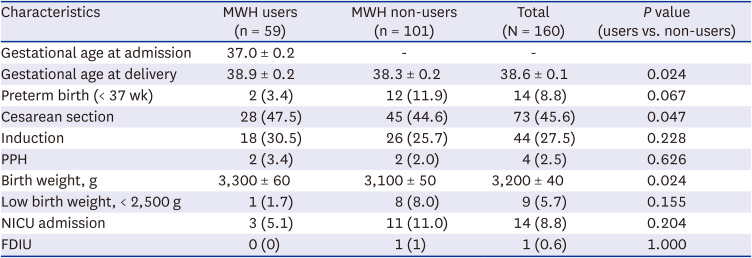

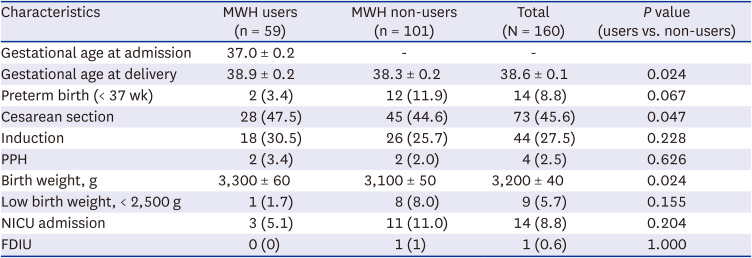

Pregnancy outcomes

MWH users had a significantly longer gestational age at birth (38.9 ± 0.2 vs. 38.3 ± 0.15 weeks,

P = 0.024) and a heavier birth weight (3,300 ± 60 vs. 3,100 ± 50 gm,

P = 0.024) compared with non-users at the time of childbirth. Although the preterm birth (< 37 weeks) rate was lower in MWH users, the difference was not significant. The rate of Cesarean section was significantly higher in MWH users than non-users (47.5% vs. 44.6%,

P = 0.047). Although the induction rate was higher in MWH users than non-users, the difference was not significant. MWH users tended to be associated with a lower NICU admission rate, birth weight (< 2.5 kg), and fetal death rate in utero compared with non-users, but the differences were not significant (

Table 3).

Table 3

Pregnancy outcomes of MWH users and non-users

|

Characteristics |

MWH users (n = 59) |

MWH non-users (n = 101) |

Total (N = 160) |

P value (users vs. non-users) |

|

Gestational age at admission |

37.0 ± 0.2 |

- |

- |

|

|

Gestational age at delivery |

38.9 ± 0.2 |

38.3 ± 0.2 |

38.6 ± 0.1 |

0.024 |

|

Preterm birth (< 37 wk) |

2 (3.4) |

12 (11.9) |

14 (8.8) |

0.067 |

|

Cesarean section |

28 (47.5) |

45 (44.6) |

73 (45.6) |

0.047 |

|

Induction |

18 (30.5) |

26 (25.7) |

44 (27.5) |

0.228 |

|

PPH |

2 (3.4) |

2 (2.0) |

4 (2.5) |

0.626 |

|

Birth weight, g |

3,300 ± 60 |

3,100 ± 50 |

3,200 ± 40 |

0.024 |

|

Low birth weight, < 2,500 g |

1 (1.7) |

8 (8.0) |

9 (5.7) |

0.155 |

|

NICU admission |

3 (5.1) |

11 (11.0) |

14 (8.8) |

0.204 |

|

FDIU |

0 (0) |

1 (1) |

1 (0.6) |

1.000 |

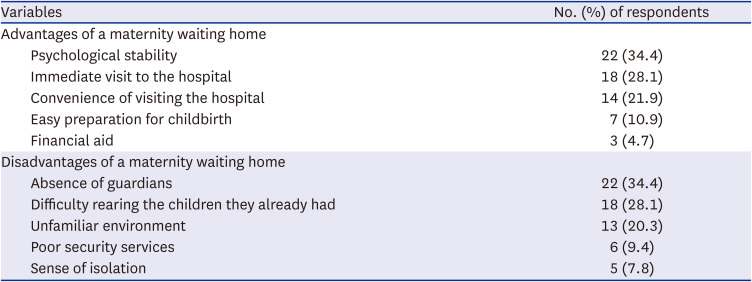

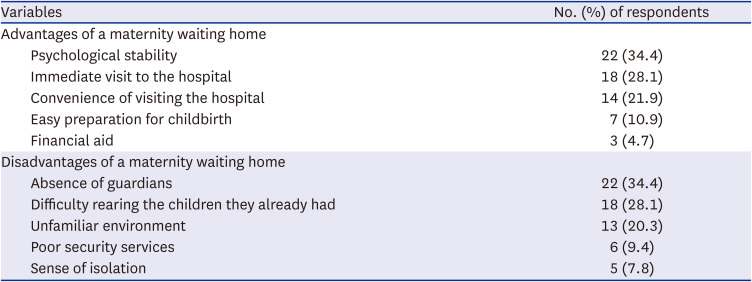

Advantages and disadvantages of the MWH

Of the 64 MWH users, 34.4% and 28.1% specified “psychological stability” and “immediate visit to the hospital in an emergency” as advantages of the MWH, respectively. Approximately 34.4% specified “absence of guardians” and 28.1% “difficulty rearing the children they already had” as disadvantages of the MWH (

Table 4). The annual total operating cost of the MWH is 55,397,260 won (3,077,625 won/person).

Table 4

The advantages and disadvantage of a maternity waiting home (N = 64)

|

Variables |

No. (%) of respondents |

|

Advantages of a maternity waiting home |

|

|

Psychological stability |

22 (34.4) |

|

Immediate visit to the hospital |

18 (28.1) |

|

Convenience of visiting the hospital |

14 (21.9) |

|

Easy preparation for childbirth |

7 (10.9) |

|

Financial aid |

3 (4.7) |

|

Disadvantages of a maternity waiting home |

|

|

Absence of guardians |

22 (34.4) |

|

Difficulty rearing the children they already had |

18 (28.1) |

|

Unfamiliar environment |

13 (20.3) |

|

Poor security services |

6 (9.4) |

|

Sense of isolation |

5 (7.8) |

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that the MWH helped improve the accessibility of a maternity hospital to pregnant women in obstetrically underserved areas and to lengthen their gestation. As a result, the neonatal birth weight of the MWH users was heavier than that of non-users. Accessibility to a maternity hospital is closely related to maternal and neonatal health in Korea. Areas with low delivery rates in the jurisdictions of local governments also have high rates of abortion, postpartum hemorrhage, and puerperal infection. Thus, improving accessibility to maternity hospitals has been recommended.

9

The travel time and distance to a maternity hospital are very important. According to a 2019 report, preterm pregnant women should arrive at the hospital within 31–40 minutes, those with placental abruption should arrive within 51–60 minutes, and those with preeclampsia should arrive within 51–60 minutes to curb their increased risk. Thus, the travel time between the residence and maternity hospital should be 31–60 minutes.

10

The travel distance to a maternity hospital depends on the location of residence. Pregnant women in Seoul travel 1.1 km to a maternity hospital on average, and those in metropolitan areas travel 3.9 km, whereas those in the Gun area travel 24.1 km, which was 24 times longer than the travel distance of those in Seoul.

3

According to this study, the average distance between the MWH and maternity hospital for MWH users was 2.7 km, which was 55.6 km closer than the distance from their original residence, and the travel time was 10.7 minutes, which was 54.1 minutes shorter. In other words, the accessibility of a maternity hospital to pregnant women staying at the MWH improved to the level of that in a metropolitan city.

MWHs improve accessibility to maternity healthcare and thereby improve maternal and neonatal health.

11 According to studies that assessed the correlation between neonatal morbidity and delivery time, the neonatal morbidity rate increases for births occurring before 39 weeks of gestation. As a result, early term was defined as before 39 weeks of gestation and term as after 39 weeks of gestation. Births after 39 weeks of gestation are recommended to decrease neonatal morbidity.

12 In this study, MWH users had a gestational period close to 39 weeks and infants with significantly heavier birth weights compared with non-users of the MWH.

According to Poovan, MWH users have better pregnancy outcomes compared with non-users. The abnormal delivery rate was lower for MWH users than non-users (61/142 [42.9%] vs. 348/635 [54.8%]). The perinatal mortality rate was significantly lower for MWH users than non-users (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.03, 0.25). However, the Cesarean section rate was significantly higher for MWH users than non-users (adjusted OR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.83, 4.25).

13 In the meta-analysis by Smith et al. in 2022, MWHs have a protective effect on maternal and perinatal mortality but fail to reduce the rate of Cesarean sections.

14 MWH users and non-users suffered no maternal or perinatal mortality in this study because Korea has a relatively better medical healthcare system than other low-income countries and because there was a small data sample.

MWH users tended to have lower rates of preterm birth (< 37 weeks of gestation), low birth weight (< 2.5 kg) infants, and NICU admission compared with non-users, but the differences were not significant. The Cesarean section rate was significantly higher in MWH users than non-users, as reported by other studies, because MWH users had more opportunities to visit the hospital, and therefore their fetal and maternal abnormalities were detected earlier and actively treated. The results of this study suggest that MWH use was most helpful in terms of psychological stability, and the absence of guardians was a disadvantage of using the MWH.

This study had some strengths. First, we reported the operating experience of an MWH and pregnancy outcomes for the first time in Korea. Second, we presented a variety of pregnancy outcomes from maternity hospitals, compared with related studies in which pregnancy outcomes were limited to maternal mortality, perinatal mortality, and Cesarean section. Third, unlike other MWH studies for low-income countries, this study was about MWH in Korea with an established national health care system.

Although the Korean MWH operating methods were different from those in low-income countries, they improved accessibility to maternity hospitals and improved pregnancy outcomes. In particular, one MWH in the obstetrical service area can help high risk pregnant women living in five underserved areas.

MWHs in Korea can be an alternative to improve the accessibility of maternal healthcare for pregnant women living in obstetrically underserved areas, where it is difficult to establish a maternity hospital and improve pregnancy outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors appreciate Ji Yeong Lee, U Jeong Nam, and Min Ho Lee for maintaining the MWH. Also, we thank Gangwon-do and the Ministry of Health and Welfare for supporting MWH's operating expenses.

References

1. Se JL, Kim YJ, Shin H, Lee T, Lee B, Hong HJ, et al. Current status of the delivery rate within the jurisdiction of local government in Korea. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2022; 26(2):112–119.

2. Lee SJ, Li L, Hwang JY. After 20 years of low fertility, where are the obstetrician-gynecologists? Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2021; 64(5):407–418. PMID:

34265193.

3. Hwang JY. Limitation and improvement plan of maternity healthcare delivery system in Korea. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2021; 25(4):250–259.

4. Kwak MY, Lee SM, Lee TH, Eun SJ, Lee JY, Kim Y. Accessibility of prenatal care can affect inequitable health outcomes of pregnant women living in obstetric care underserved areas: a nationwide population-based study. J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 34(1):e8. PMID:

30618515.

7. van Lonkhuijzen L, Stekelenburg J, van Roosmalen J. Maternity waiting facilities for improving maternal and neonatal outcome in low-resource countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 10(10):CD006759. PMID:

23076927.

9. Choi YH, Na BJ, Lee JY, Hwang JH, Lim NG, Lee SK. Obstetric complications by the accessibility to local obstetric service. J Agric Med Community Health. 2013; 38(1):14–24.

10. Kwak MY, Lee SM, Kim HJ, Eun SJ, Jang WM, Jung H, et al. How far is too far? A nationwide cross-sectional study for establishing optimal hospital access time for Korean pregnant women. BMJ Open. 2019; 9(9):e031882.

11. Ahn TG, Hwnag JY. Maternity care system for high risk pregnant women in obstetrically underserved area. J Korean Med Assoc. 2016; 59(6):438–442.

12. Spong CY, Mercer BM, D’Alton M, Kilpatrick S, Blackwell S, Saade G. Timing of indicated late-preterm and early-term birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 118(2):Pt 1. 323–333. PMID:

21775849.

13. Poovan P, Kifle F, Kwast BE. A maternity waiting home reduces obstetric catastrophes. World Health Forum. 1990; 11(4):440–445. PMID:

2092704.

14. Smith S, Henrikson H, Thapa R, Tamang S, Rajbhandari R. Maternity waiting home interventions as a strategy for improving birth outcomes: a scoping review and meta-analysis. Ann Glob Health. 2022; 88(1):8. PMID:

35087708.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download